Lafayette had returned to America to ‘see for himself the fruit borne on the tree of liberty’

On August 16, 1824, when Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, descended the gang-plank of a ship in New York Harbor, he was greeted by a group of aging veterans wearing patched-up uniforms and standing on rickety limbs. Each old soldier snapped out his name and company and the battle where he had served with Lafayette during the American Revolution: “Monmouth, Sir!” “Barren Hill, Sir!” “Brandywine, Sir!”

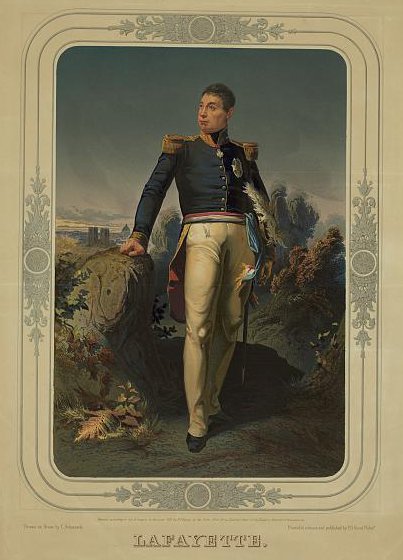

The years had taken their toll on Lafayette since he helped defeat the British as one of George Washington’s most trusted generals and advisers and then returned to his homeland to participate in the French Revolution. Steadying himself with a cane now at age 66, he took a few moments to survey the scene at the foot of Manhattan—young militia drawn up smartly for the gala parade up Broadway to City Hall, bands playing, cannon booming, church bells pealing—and burst into tears.

New York City marked the beginning of a triumphal 13-month tour that would take Lafayette to all 24 states of the young republic. He had returned to America at the invitation of President James Monroe and the U.S. Congress to “see for himself the fruit borne on the tree of liberty.” Enormous crowds gathered everywhere he went to catch a glimpse of the last surviving general from America’s fight for independence. “Half a century had carried all of his contemporary actors of the Revolution in the great abyss of time,” wrote James Fenimore Cooper, “and he now stood like an imposing column that had been reared to commemorate deeds and principles that a whole people had been taught to reverence.”

New York City marked the beginning of a triumphal 13-month tour that would take Lafayette to all 24 states of the young republic. He had returned to America at the invitation of President James Monroe and the U.S. Congress to “see for himself the fruit borne on the tree of liberty.” Enormous crowds gathered everywhere he went to catch a glimpse of the last surviving general from America’s fight for independence. “Half a century had carried all of his contemporary actors of the Revolution in the great abyss of time,” wrote James Fenimore Cooper, “and he now stood like an imposing column that had been reared to commemorate deeds and principles that a whole people had been taught to reverence.”

Unfortunately, the spirit of 1776 had faded as America expanded westward. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 papered over festering sectional rivalries by balancing Missouri’s admission to the union as a slave state with Maine’s admission as a free state. But by setting a geographical boundary on slavery, the compromise also effectively defined a line on which the nation might split apart. Lafayette’s old friend Thomas Jefferson likened it to “a fire bell in the night [that] filled me with terror. I considered it at once as the knell of the Union. It is hushed, indeed, for the moment. But this is a reprieve only, not a final sentence.”

The first months of Lafayette’s tour coincided with a bitterly divisive presidential campaign, which brought James Monroe’s two-term Era of Good Feelings to an end. Monroe ran unopposed four years earlier, but now the host of candidates who threw their hats in the ring seemed unable to agree on anything but the apparent certainty that the union was on the verge of collapse.

America was in desperate need of a hero.

Lafayette was also in desperate need of an emotional lift after being frustrated in his decades-long quest to bring American-style liberty to his homeland. When violent factions took control of the French Revolution in 1791, he tried to flee to America through the Dutch Republic but was captured by Austrians and spent nearly five years in prison. More recently, he had lost his wife and his elected seat in the French national assembly. He hoped that positive reports from the American tour would filter back to Europe and promote the republican impulse he still hoped to implant in his native soil.

Lafayette’s reception in America exceeded his fondest expectations. After four days in New York City, including a formal banquet and ball with 5,000 guests said to be the most elaborate yet staged in America, he headed by carriage for Boston and Philadelphia—landmarks of the revolutionary spirit he embodied. He and his entourage, which consisted of his son, George Washington Lafayette, his private secretary, Auguste Levasseur and his valet, Bastien, were repeatedly delayed along the way. They could not pass even a hamlet without being detained there for formal greetings accompanied by military escort, cannon salutes and, typically, grizzled old veterans of the Revolution.

People waited for them at all hours, under a hot sun or driving rain, through nights lit by bonfires. Mayors welcomed them. Preachers prayed for them. Then Lafayette would limp forward to express his delight and appreciation. “The approbation of the American people,” he would say at practically every stop, “is the greatest reward I can receive.”

In Philadelphia, the parade route passed through hastily assembled arches intended to resemble the Arc de Triomphe being built in Paris. Up to 40 feet high and 50 feet across, these arches were fashioned from wood frames covered with stretched canvas painted to resemble granite blocks. There were 13 of them, one for each of the original colonies.

A procession of 20,000 marchers streamed through the arches and past bleachers erected by enterprising Philadelphia homeowners who charged 25 to 50 cents a seat for each spectator. Weavers, coopers, butchers and other tradesmen had their own horse-drawn floats demonstrating what they did for a living. The printers’ float bore a huge sign extolling freedom of the press and an actual press, which cranked out odes to Lafayette that were tossed into the general’s magnificent carriage and handed out to the multitudes.

Lafayette’s temporary headquarters in Philadelphia was Independence Hall, which had been renovated and restored for his visit. The building had stood empty and deteriorating after Congress had moved to Washington City 25 years previously. There, in the room in which the founding fathers—many of them his friends—signed the Declaration of Inde-pendence, he received endless lines of teachers, children, weeping veterans and fathers leading their sons up to touch the hand of the legendary hero. He had a smile or cordial word for everyone, winning hearts with what a writer called his “great goodness and affability.”

People marveled at his endurance. But in fact Lafayette loved it all. Unlike his old wartime commander George Washington, he relished being the center of attention. He liked to point out that he had dropped the title “marquis” early in the French Revolution. But when people assumed that his limp was the legacy of his leg wound suffered at Brandywine, he did not bother to explain that it had actually resulted from an improperly set fracture after a fall in Paris. As James Madison observed many years before, he appeared to possess a “strong thirst of praise and popularity.” And he felt completely at home among Americans. When a university dignitary expressed surprise at his command of English, Lafayette responded, “And why would I not speak English? I am an American, after all—just back from a long visit to Europe.”

In Baltimore, returning to his lodgings one night, Lafayette felt a tug on his coat. He turned around, his secretary Auguste Levasseur wrote, “and saw a young girl, beautiful as the day, her hands folded, crying out in the most moving tone of voice: ‘Ah! I beg of you, let me touch his clothes, and you will have made me happy.’ General Lafayette heard her, walked towards her and held out a hand which she seized and kissed with rapture, after which she ran away while hiding her tears and her blush in her handkerchief.”

When Lafayette arrived in America, newspapers were filled with vitriol as the presidential campaign devolved into a contest pitting the interests of the North—represented by John Quincy Adams—and the South and West—represented mainly by Andrew Jackson. But soon Lafayette’s tour “paralyzed all the electoral ardour,” observed James Fenimore Cooper. “At the public dinners, instead of caustic toasts, intended to throw ridicule and odium on some potent adversary, none were heard but healths to the guest of the nation, around whom were amicably grouped the most violent of both parties. Finally, for nearly two months all the discord and excitement produced by this election, which, it was said, would engender the most disastrous consequences, were forgotten, and nothing was thought of but Lafayette and the heroes of the revolution.”

Lafayette himself, in a letter home, concluded that his trip had “contributed to tighten the union between the states and to soften political parties, by bringing them all together in common hospitality toward a ghost from another world.”

The Frenchman’s aim to influence events back home met with less success. As American newspapers chronicled in minute detail virtually every movement of Lafayette’s tour, his secretary Levasseur served as his personal publicist. He sent to French periodicals clippings and copies of his speeches in America. Governmental censorship kept much of this out of the French press. But Levasseur also maintained a detailed journal, which was later published in serial form and as a book, predating by six years the vivid picture of American life presented by another Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville.

The official French view of the tour came from the monarchist French minister to America, Baron de Mareuil. Lafayette’s words, he told his superiors in Paris, were less “homage to America than an appeal to the revolutionary passions in Europe, a wish for their success and for the complete triumph of democracy.” As Lafayette neared Washington that October, the baron haughtily reported that he would refuse “any invitation, even from the president, to any festivity for M. de Lafayette.”

When Lafayette met with President Monroe at the White House, he was astonished at the lack of pretension in the one-story dwelling and its principal occupant. It was “a very simple house,” observed Levasseur. Not a guard was in sight; a single domestic servant opened the door and showed them to the Cabinet room, where the president was seated in a simple blue suit. This stunned Levasseur who expected “those puerile ornaments which so many ninnies wear in the ante-chambers of the palaces of Europe.”

A few days later, Lafayette made an emotional pilgrimage to Mount Vernon, home of America’s first president. When Lafayette joined the Continental Army at age 19, Washington became his wartime commander, mentor and something of a substitute father. Later, when things became difficult in Paris during the French Revolution, Lafayette sent his son George to live for two years at Mount Vernon. Now the aging Frenchman descended alone into Mount Vernon’s burial vault, knelt before Washington’s coffin and emerged some minutes later, Levasseur wrote, “his face inundated with tears.” One of Washington’s nephews presented him with a golden ring containing some of the great man’s hair.

Lafayette’s subsequent visit with his old friend Thomas Jefferson, then 81, was lighthearted. During a 10-day stay at Monticello, Jefferson asked that he converse only in French instead of English. There was much good talk and apparently an abundance of good wine. After Lafayette departed, Jefferson had to replenish nearly all of the red wines in his cellar.

The 1824 presidential campaign drew to a contentious close during Lafayette’s winter sojourn in Washington. Andrew Jackson, a senator from Tennessee and the hero of the War of 1812, had won the most popular and electoral votes but lacked the majority of electoral votes required by the Constitution. Under the 12th Amendment, the election would have to be decided by the House of Representatives.

Lafayette had known the runner-up in the electoral vote, John Quincy Adams—son of the second president—as a young boy. He also had come to know and like Jackson on this visit. But he maintained a strict silence as to his preference, realizing that he needed to be a symbol of national unity at a time of peril to the republic. All the candidates attended Washington festivities for Lafayette, including his address to a joint session of Congress—first ever by a foreigner. At a congressional banquet they heard Lafayette pointedly toast “the perpetual union of the United States. It has always saved us in times of storm; one day it will save the world.”

On February 9, 1825, the House of Representatives elected Adams. His victory was made possible by the supporters of Henry Clay, who had finished fourth in the electoral vote. Jackson’s angry supporters charged that Adams, in “a corrupt bargain,” had promised to make Clay his secretary of state. But when President Monroe held a reception for the president-elect, Lafayette beamed as Jackson stepped forward to congratulate Adams and pledge his loyal support.

The grand tour resumed southward in March 1825. In southeastern North Carolina Lafayette fairly burst with pride as he entered Fayetteville, the first of the American towns named for him. In subsequent years more than 600 American villages, cities, counties, mountains, lakes, rivers, educational institutions and other landmarks would bear his name or that of his chateau at La Grange in France. And a newly coined word—“fayetted”—came to signify giving someone an extravagant welcome.

Traveling by carriage or stagecoach on the rutted roads and primitive wagon trails of the South tested the entourage. The jolts and lurches were so tortuous that Lafayette occasionally fell ill. In South Carolina overflowing rivers blocked their way, and the shaft of their carriage broke in the middle of a bog. A 60-mile trip took nearly two days. When possible, they boarded steamships for trips into Georgia, Alabama and Louisiana. Lafayette was rejuvenated by a 10-day cruise up the Mississippi River to St. Louis aboard the Natchez—a luxury steamship carrying a famous New Orleans chef, an orchestra and a large staff of maids and butlers.

Later, on the Ohio River, Lafayette had his closest call of the tour. Near Shawneetown, Ill., his steamship struck a submerged tree trunk and sank. Son George and Levasseur rushed into Lafayette’s cabin, led him up on deck and lowered him into the captain’s lifeboat. While the ship settled into the river mud, the lifeboat reached the Kentucky shore, where Lafayette spent the night on a soaked mattress that had floated out of the wreckage.

Though Lafayette long had opposed slavery, he did not publicly proclaim his views on an issue that he knew sharply divided Americans. Nor did he publicly object to the fact that black men were prohibited from attending his festivities in the South and from banquets in the North. But in private in New Orleans he challenged convention by warmly receiving a group of free black men who had fought under Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans.

Lafayette also took a keen interest in another ethnic group spurned by many Americans. A number of American Indians had served under his command in the Revolution. A chief from the Creek nation who met with Lafayette along the Georgia-Alabama border called him “the favorite father of all races of men who inhabit this continent.” In the southern Illinois frontier town of Kaskaskia, he encountered a young Indian woman named Mary who showed him a family memento from the Revolution that she always carried in a leather bag around her neck. It was a letter Lafayette had written in 1778 from his headquarters in Albany, N.Y., to her late father—“Panisciowa, chief of one of the six nations”—thanking him for his courageous service under his command.

The most important ceremony commemorating the Revo-lution brought Lafayette back to Boston to mark the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. On June 17, 1825, an estimated 200,000 onlookers lined the roads leading to this venerated place where patriots besieging Boston had demonstrated they could stand and fight and hold their own against regular British troops.

The ceremonies on Bunker Hill that day began with the dedication of a monument memorializing the battle. Lafayette, a grand master of the Masonic order, was called upon to lay the cornerstone—a ceremonial task he had happily performed previously for a number of buildings and monuments on his tour. Then the famed orator, Congressman Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, delivered a long and stirring speech before 15,000 spectators seated in a wooden amphitheater built around the crest of Bunker Hill. After paying tribute to the old veterans of the battle, Webster turned to Lafayette. “You are connected with both hemispheres and with two generations,” he intoned. “Heaven saw fit to ordain the electric spark of liberty should be conducted, through you, from the New World to the Old.”

Lafayette and some 4,000 others then sat down at a banquet under an enormous wooden canopy. It was, he wrote to his children in France, “the most beautiful patriotic fete ever celebrated.” To this assemblage he offered a toast with a provocative hope that resonated back home in Europe: “Bunker Hill and the holy resistance to oppression, which has already liberated the American hemisphere. The anniversary toast at the jubilee of the next half-century will be to liberated Europe.”

After traveling northward to Maine and Vermont, fulfilling his pledge to visit all 24 states, he reached New York City in time for the Fourth of July celebration. He began the 49th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence by laying a cornerstone in Brooklyn Heights for the Apprentices Library intended for the use of working-class children.

The poet Walt Whitman remembered Lafayette arriving there in “a canary yellow coach.” Whitman was 6 years old, among a group of schoolchildren brought to the ceremony. So that the children could see above the heaps of stones, men held up several of them. Lafayette himself lifted up young Whitman, kissed his cheek and then set him down to watch as he laid the cornerstone. The memory of it many years later, Whitman wrote, bore an “indescribable preciousness.”

At the end of his grand tour, Lafayette accepted the invitation of President John Quincy Adams to spend a quiet month as his personal guest in the White House. On September 6, 1825, a gala dinner celebrated the visitor’s 69th birthday, and Adams took the occasion to break the protocol established by Washington that the president should not propose formal toasts. He raised a glass to the birthdays of both Washington and Lafayette. The Frenchman replied with his own toast: “To the 4th of July, the birthday of liberty in the two hemispheres.”

Three days later, Lafayette and his entourage embarked for home on a new navy frigate, the USS Brandywine, commissioned in honor of the Nation’s Guest. He had been offered a warship for his journey to America 13 months previously but modestly turned it down in favor of commercial passage paid for by borrowing money and selling some of his cattle. Now, he gratefully accepted the offer of a free ride home.

He took home trunks full of mementoes and gifts bestowed upon him by well wishers in America. These included new-found wealth authorized by Congress to replenish his depleted personal treasury: a grant of $200,000 (the equivalent of more than $4 million in today’s dollars) and 24,000 acres of public land in the northern part of the territory of Florida, which he later sold and now comprises much of the city of Tallahassee. Canvas sacks held dirt he had dug up from the hallowed ground on Bunker Hill.

He left behind a new surge of nationalism and patriotic pride. The sense of national unity that he helped create would not split fully asunder until the Civil War 36 years later.

When Lafayette died in 1834, he had yet to see liberty prevail in his homeland, but the soil from Bunker Hill—symbolic of American freedom—was sprinkled over his grave in Paris.

Ronald H. Bailey, author of several World War II and Civil War books, was an editor for the original Life magazine.