[dropcap]T[/dropcap]heir faces peer out at us from photographs now some 150 years old. These solemn men, five general officers of the Confederacy, stand or sit proudly for their portraits, each resplendent in his gray uniform. We’ve seen these images and hundreds others like them for generations. But these five men have a secret. There’s a reason you might notice a twinkle in their eyes because these images, seemingly so pedestrian, are unlike any others of their kind.

The uniforms of the Confederate generals were anything but uniform. There were numerous variations on the theme and their clothing was as diverse as the wearers. Like the generals themselves, it seems that no two of their uniforms were exactly alike.

Yet at least nine Confederate officers—generals and others of lesser rank—had posed for studio portraits wearing the same uniform coat, which may have been a photographer’s prop. That discovery was published in the October 2014 Civil War Times.

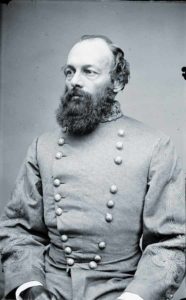

At the time that article was published, I realized I had seen another uniform worn by more than one general. P.G.T. Beauregard’s best-known portraits were all taken in this uniform at a single sitting. He wears a dazzlingly handsome coat, well-tailored, and of expensive fabric. Its massive collar insignia is distinctive and Hungarian knot reaches up the coat sleeve nearly to the shoulder. Two rows of buttons, grouped in threes and in a graceful bow, descend to the waist, narrowing as they go.

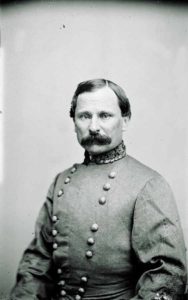

I had noticed years ago that two other generals, Edmund Kirby Smith and Mansfield Lovell, also posed for pictures wearing what I then believed was a similar uniform. Beauregard, Smith, and Lovell all had connections to Louisiana and my assumption was that the three had purchased their uniforms from the same tailor. But I began to wonder whether Smith and Lovell might not be wearing a coat similar to Beauregard’s, but rather the same coat.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Why were these men wearing the same uniform?[/quote] Looking at the buttons, one can see that the sixth one down on the right is slightly out of line with the others, and the buttons become downright sloppy at the waistline, as if hastily sewn on. A general wrinkling pattern can be seen flowing diagonally across the chest and under magnification one can see certain wrinkles identical in each portrait. Sure enough, Beauregard, Smith, and Lovell wore the same coat in their portraits.

Oddly, Beauregard also took the opportunity at this sitting to be photographed in civilian clothes, a handsome black suit with vest and a smart, striped necktie. A comparison of these views of Beauregard in uniform and civilian dress shows his hair groomed and falling in exactly the same manner, and in the uniformed images the striped tie also shows itself peeking up through the gap in the collar.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap] wondered if there could have been others photographed in this coat. Looking through my digital cache of images I found two more generals, Cadmus Wilcox and Thomas Clingman, wearing it. Out the window went my theory of the Louisiana connection: Wilcox and Clingman never got near the Bayou State during the war.

So when and where were these images taken and why were these men wearing the same uniform? We have two generals who were strictly Eastern Theater men, Wilcox and Clingman; two Western Theater generals, Smith and Lovell; and Beauregard, who served in both. Richmond, being the seat of the Confederate government, would surely have been a place each man could have visited. Perhaps a local photographer there owned this fine coat and these men posed in it while in the city. It’s a simple solution, but one too hastily accepted, for again we must look closely for details that reveal the truth.

P.G.T. Beauregard (National Archives)

Each of these five men fortunately struck several poses during their sittings, and it is the standing pose of Lovell that generated a series of connections leading to a stunning revelation. Lovell is well turned out in the uniform—which fits him perfectly—and he rests his left hand on a stack of books atop a small side table. The table’s skirt bears distinctive ornate geometrical carvings. This same table and books can also be seen in sitting and standing portraits of Confederate Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson. The chair in which Robertson sits is likewise decorated with distinctive carvings.

So now we have two distinctive props—a table and a chair—that might be used to identify a particular photographer. They can be seen singly or together in images of a number of civilians, male and female, and I became comfortable with the notion that these images were produced by a Richmond photographer.

My theory was laid low by the appearance of an image of a Federal army officer standing dolefully with his left elbow resting on the distinctive chair. But how? This made no sense! How did a Federal officer come to be photographed in the same studio as Confederate generals?

I then examined an image of General Robertson seated at that same table and chair, and that photo provided an answer so obvious I nearly missed it. In wartime images Robertson’s hair and beard were dark, nearly jet black early in the war, and graying by the end of the war. In the images with the chair and table his hair and beard are very gray and thinning, and the never-slender Robertson has grown far more corpulent, nearly busting out of his uniform. But of far greater importance was the realization that many of the images showing the table and chair can be found in online collections credited to the work of the Mathew Brady studios.

Brady images? Of Confederate generals? That could mean only one thing: the photos of these generals had to have been taken postwar. If that fact had ever been known at all, it had been long ago lost to history. What a discovery! But I still had to verify it and also pin down the studio location. Brady operated studios in Washington and New York City. My first clue that these were taken in New York was that one of the women pictured with the table and chair is identified as “Mrs. Astor.” That name certainly conjures up New York associations. An e-mail quickly went out to the New York Historical Society and their reply confirmed—the table and chair were props strictly associated with Brady’s New York studio.

What a profound moment it was to realize that former Confederate generals posed in uniform after the war in New York, at the studio of America’s most famous photographer. It explains why Beauregard was photographed in both military and civilian attire, as was Clingman. It explains why a Federal officer had his picture taken in the same studio as Confederate officers. It explains how generals of the Eastern and Western theaters were photographed in the same studio. But it does not explain why they were wearing the same coat.

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]uring a Google search I found a modern color photo of a Confederate general’s uniform on display in a museum, mounted in a glass case. At once I recognized the collar insignia. Quickly checking the buttons, I saw the sixth one down out of line and the messy arrangement of the buttons at the bottom. There was even diagonal wrinkling still present across the chest. This was it! This was the very uniform worn by Beauregard and the other four generals in the Brady portraits, still in existence and on display somewhere.

The image came from a Wikipedia page, admittedly not a source known for ironclad accuracy, and the caption under it read, “Uniform coat of Gen. Mansfield Lovell, Confederate Memorial Hall.” I knew that the long-time Confederate museum is in New Orleans. I called and spoke with the museum’s executive director. To my disappointment, she informed me that the museum did not have that uniform. I directed her to the Wikipedia page so she could see the image for herself. After a few moments she said, “Well, it’s not in our museum, but I think I know where it is.”

She directed me to the Louisiana State Museum, also in New Orleans. Soon I was on the phone to Wayne Phillips, the museum’s curator of costumes and textiles. Indeed, that uniform was in the museum’s possession, a gift of Lovell’s descendants in the 1970s, but only recently conserved and placed on display. No wonder it fit Lovell so perfectly in his photographs. It was his own uniform. Of the five generals wearing it, Lovell was the only one who accessorized it with his sash and sword belt, which are also on display.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]My eyes rested on a uniform I never thought I would see[/quote] Some months later, when I visited the museum near Jackson Square, Phillips conducted me to the third floor. There my eyes rested on a uniform I never thought I would see. It is one of the most beautiful of Confederate generals’ uniforms and looks precisely as it does in the standing picture of Lovell. The points of the collar stars line up exactly with the leaves of the wreath as seen in the Brady photos. Identical wrinkles can be identified on the uniform today that can be seen in the images. And then there are those messy buttons. The collar and cuffs, which appear in the photos to be the same gray color as the rest of the coat, are instead regulation buff. This, however, is not uncommon in the era’s collodion photography.

There is no doubt this is the uniform worn by the five generals postwar at Brady’s studio. What a sensation to view this uniform after having “chased” it through photos for what seemed years!

It makes sense that if former Confederate generals were photographed in uniform after the war in New York City the uniform would belong to Lovell, for he made his home there after the war, as he had done prewar. But when were these images made? Were they all taken at the same time or separately? Beauregard was a railroad executive in the immediate postwar years, which certainly brought him to New York on at least one occasion. Clingman was a land agent in western North Carolina and spent much time in New York after the war. Wilcox made his home in Baltimore and then Washington by the 1870s and could have easily gone to Manhattan for business or pleasure at any time. It could be that a few of them found that they were staying in the same hotel enjoying cigars and renewing acquaintances. Perhaps one suggested they all go to Brady’s and have their pictures taken, and Lovell said, “By the way, I, ah, happen to have my uniform…” One can imagine the banter at the studio. “Seems a bit snug on you there, Smith.” “My God, Lovell, did you wear this in the circus?”

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]here is a strong possibility that a special event brought at least some of these men together at the same time in New York City. Robert E.L. Krick, historian at Richmond National Battlefields, suggested I look into the meetings of the Aztec Club of 1847, a social organization of former army officers who were together in the Mexican War. A meeting of that club was held September 14, 1867, at Astor House in New York. Beauregard, Smith, Wilcox, and Lovell were all members of the Aztec Club. Clingman was not, but it could be that he was in Manhattan at the time of the meeting on one of his frequent visits.

Mansfield Lovell (National Archives)

But because Lovell was living in New York and had his uniform, it isn’t necessary that all five generals had their portraits made at the same time—and in fact it seems unlikely. We can with some accuracy date Edmund Kirby Smith’s sitting. A letter by Smith answering a man seeking his autographed picture was recently offered for sale by an artifact dealer. In it Smith apologizes for the quality of the enclosed image, saying that a much better one had been taken by “Brady of New York some nine months since.” Smith’s letter is dated July 21, 1866. If by “nine months since” Smith meant “nine months ago” then Smith’s image was taken roughly in October 1865. Smith is also listed among passengers arriving in New York aboard a steamer during that period.

But that time range rules out the concurrent presence of Cadmus Wilcox. According to his biographer, Wilcox traveled to New York immediately after Appomattox and there boarded a ship bound for Texas. Wilcox went on to Mexico, where he was photographed in Mexico City with other former Confederate generals on October 8, 1865, and remained in that country until the following year when he relocated to New Orleans. It is possible that Wilcox attended the 1867 meeting of the Aztec Club at the Astor House. But he could not have been photographed at the same time as Smith.

The lesson that lies within all of this is that we cannot always judge an image by its gutta percha cover. Outdoor images of troops in camp or on garrison duty always seem to contain lots of interesting facets upon close examination. But we now know that the same can be said for the supposedly mundane images of men simply sitting in a chair in the controlled environment of the photographer’s studio. Beware of the neutral expression on that subject. He or she just might be hiding a secret.

Gulfport, Miss., native Richard Lewis is a retired public relations director for the Virginia Tourism Corporation and serves as secretary for Civil War Trails, Inc. He and his wife, Mary, reside in Richmond.

Online Extra: More Pictures & Another Coat Peruse more images related to Mathew Brady’s New York studio and the General Lovell coat intrigue, and read about yet another Confederate uniform Richard Lewis has researched that appears in numerous images.