‘The British interned Rutland as a collaborator under Defence Regulation 18B—a wartime statute that allowed for the indefinite detainment of British nationals suspected of enemy sympathies’

“There seems to be something wrong with our bloody ships today.”

Thus Vice Adm. Sir David Beatty, commander of the Royal Navy’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, famously exclaimed after watching the 26,770-ton HMS Queen Mary blow in two and sink. The destruction of one of the British fleet’s largest warships came only minutes after German ship-to-ship fire sank the 18,500-ton battlecruiser HMS Indefatigable. Both British capital ships went to the bottom of the North Sea on the afternoon of May 31, 1916, in the opening phase of the Battle of Jutland.

Beatty’s quote is well known among naval and military historians. Less well known is what the vice admiral described in his after-action report to Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, about a weapon system Beatty used for the first time to confirm the location of the enemy fleet:

At 2:45 p.m. I ordered [the seaplane tender HMS] Engadine to send up a seaplane and scout to NNE. This order was carried out very quickly, and by 3:08 p.m. a seaplane, with Flight Lt. F.J. Rutland, RN, as pilot, and Asst. Paymaster G.S. Trewin, RN, as observer, was well under way; her first reports of the enemy were received on the Engadine about 3:30 p.m. Owing to the clouds it was necessary to fly very low, and in order to identify four enemy light cruisers the seaplane had to fly at a height of 900 feet within 3,000 yards of them, the light cruisers opening fire on her with every gun that would bear. This in no way interfered with the clarity of their reports, and both Flight Lt. Rutland and Asst. Paymaster Trewin are to be congratulated on their achievement, which indicates that seaplanes under such circumstances are of distinct value.

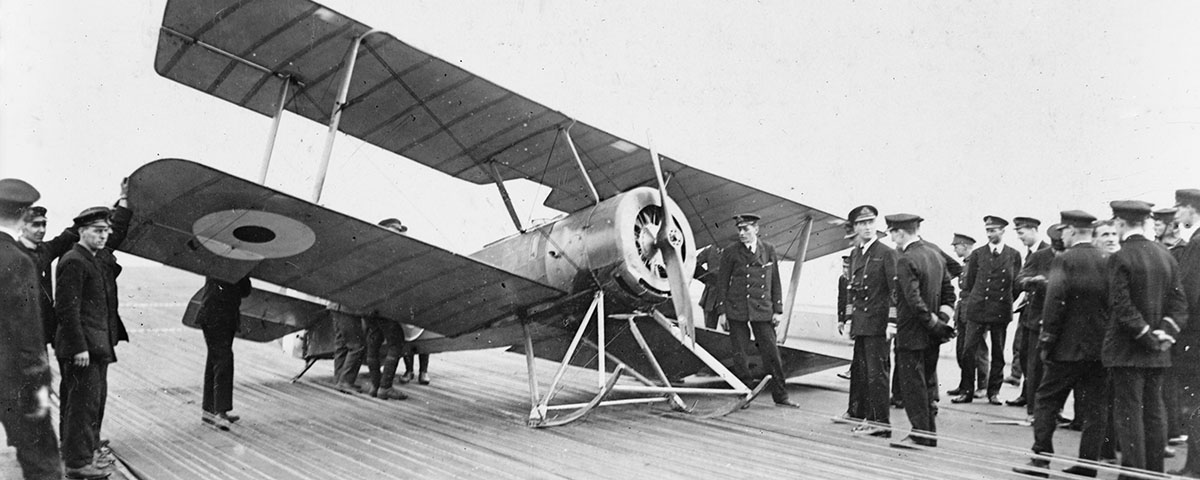

A half-hour before the opening exchange of fire between the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet off Jutland, Denmark, Flight Lt. Rutland lifted off in a Short Type 184 seaplane to make history. When observer Trewin transmitted his sighting to Engadine, it marked the first time an aircraft had sent a radio message to a fleet maneuvering for battle.

Not included in Beatty’s report were the difficulties involved in preparing an aircraft for operations at sea. The Battle of Jutland occurred nearly two years before the Royal Navy had developed a true purpose-built aircraft carrier with an extended flight deck. Engadine, the ship that carried Rutland’s Short 184 to sea, was a former cross-Channel ferry the Royal Navy had converted into a seaplane tender, fitted with a topside hangar for up to four floatplanes. Prior to launching a seaplane, the ship would first have to come to a complete stop. Crewmen would then retrieve the plane from its hangar, unfold its wings and test the engine. Shipboard cranes hoisted the seaplane from the deck and lowered it into the water. The best time the tender’s support crew had achieved in preparing a seaplane for action was 20 minutes—and that was in harbor. Yet even in the moderately rough open seas off Jutland, Engadine’s crew had Rutland’s aircraft in the water and ready for takeoff just 28 minutes after receiving Beatty’s order. It was an exceptional feat for the time, one later recognized by Jellicoe in his Jutland dispatch.

Minutes after Trewin transmitted his sighting of the German fleet to Engadine, the seaplane’s fuel pipe ruptured, forcing Rutland to make a sea landing. Leaving the cockpit, he spent nearly 10 minutes standing atop one of the Short 184’s floats to patch the break with a piece of rubber tubing. When Rutland reported the repair to Engadine and his intent to resume observation of the German fleet, he was told instead to taxi back to the tender on the surface. His reconnaissance mission was over. In his after-action report Rutland argued that his superiors had misused the reconnaissance aircraft out of a conviction that seaplanes were unreliable—owing to their record of engine failures and inability to take off in rough seas.

“It was not that Admiral Jellicoe was not air-minded, as one might suppose,” Rutland wrote. “It was just that he was incapable of adding to his organization any unit that had not been proved 100 percent efficient to his satisfaction. Thus, when [HMS] Campania, with her 14 seaplanes, all equipped with wireless, and a flight deck from which they could take off, was left behind in port because, by some extraordinary oversight, she did not get her sailing orders, his reaction, on discovering that she was far astern of the Grand Fleet, was to order her back to port again. It does not seem to have occurred to him that, even if she were 100 miles astern, her planes could still operate with the fleet. Had proper use been made of her aircraft, many of the mistakes at Jutland would have been avoided.”

Rutland’s role at Jutland, minor though it might have seemed at the time, didn’t end when the big naval guns fell silent. That evening Engadine encountered the badly damaged armored cruiser HMS Warrior and offered to render aid. The seaplane carrier took the cruiser in tow for nearly 12 hours, until it became obvious the cruiser’s bulkheads were giving way. Warrior’s commander gave the order to transfer his crew of more than 700 to Engadine and abandon ship. The transfer operation was a hazardous undertaking, as the two ships had to sail side by side in rough seas as the transfer was being made. Most of the men had made it safely across when a wounded sailor tumbled from his stretcher into the sea between the two ships. Realizing the man would be crushed should the vessels smash against one another, Rutland grabbed a rope, told several men to hang on to one end and lowered himself over the ship’s rail into the water. After swimming to the wounded sailor and taking hold of him, Rutland ordered those on deck to heave away. Moments later he and the wounded man arrived safely on deck.

For his daring reconnaissance mission Rutland received the Distinguished Service Cross. For his lifesaving efforts he received the rarely awarded gold Albert Medal.

Frederick Joseph Rutland was not, as historian Desmond Young wrote, “one of those dashing young naval officers of good family who ride hard to hounds, play polo in Malta and are the life and soul of cocktail parties in a foreign port.” Born on Oct. 21, 1886, in Weymouth, England, Rutland came from a humble background. In 1901 the 15-year-old joined the Royal Navy as a boy entrant, spending the first 11 years of his chosen career learning to be a seaman and hard-hat diver.

While attending diving school near Portsmouth, Rutland watched, mesmerized, as aircraft from the naval wing of the Royal Flying Corps flew in and out of a nearby airfield. Smitten by the allure of flight, he was determined to transfer to the RFC. He first had to complete an intense year of study and preparation for the examinations required to earn a naval commission. Assisted by a 20-year-old schoolteacher who would become his wife, Rutland passed his exams and was commissioned in 1913, a rare achievement for an enlisted sailor at the time.

Rutland proved a capable officer, and following Britain’s August 1914 declaration of war on Germany he was assigned to a torpedo boat. After five months at sea with no action, he was notified of his transfer to the recently formed Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). At age 28—considered old for a prospective pilot at the time—Rutland reported to the Royal Navy flying school at Eastchurch, on the coast of Kent 55 miles east of London.

Rutland learned the basics of flight on the dual-control Short pusher biplane. Once he had demonstrated some expertise on this aircraft and completed a solo flight, he moved on to the more advanced Farman MF.7. Rutland was given a 30-minute orientation flight on the Farman and allowed to solo after only two hours. On completion of flight training and eight hours of solo flying time, he received an international pilot’s certificate and was assigned to Calshot Naval Air Station for seaplane training. After an additional 10 hours flying Sopwith seaplanes, Rutland was deemed operationally qualified and was posted to Engadine.

After his performance at Jutland, Rutland spent the rest of the war designing, developing and testing aircraft that could take off from capital ships, as well as conceiving the requirements for the Royal Navy’s first true aircraft carriers. As technical adviser to the aircraft committee with the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron at Rosyth, Rutland counseled the Admiralty that wheeled aircraft, not seaplanes, were far more viable offensive weapons due to their greater speed, higher rate of climb and ability to engage enemy aircraft. Rutland conducted numerous experiments to develop a flying-off platform that could be mounted atop a cruiser’s main gun turrets. Leading by example, in June 1917 aboard the light cruiser HMS Yarmouth he flew a Sopwith Pup scout plane off a platform that measured just 20 feet long and didn’t interfere with operation of the ship’s forward guns. Rutland soon convinced both the Admiralty and his fellow RNAS pilots that wheeled aircraft could safely operate from cruisers.

By the end of 1917 Rutland had successfully flown aircraft off modified platforms aboard Yarmouth and the battlecruiser Repulse and had trained more than a dozen RNAS pilots to fly off the short flight deck of a cruiser. Such operations weren’t without risk. On one occasion Rutland was nearly killed while attempting to land aboard the modified battlecruiser HMS Furious in a Pup fitted with a ski-type undercarriage. On touchdown one of the aircraft’s landing skids got stuck in the deck planking, tipping the aircraft over the ship’s side. As the aircraft went over, Rutland unbuckled his straps and jumped clear of the cockpit so as not to be trapped in the wreckage when the aircraft hit the sea. He instead fell 55 feet to the water and then had to dive beneath the surface some 40 feet to avoid the ship’s propellers. When he surfaced, he swam to a seat cushion that had fallen out of the plane and treaded water until the ship’s boat retrieved him 20 minutes later.

Rutland’s wartime service proved extremely valuable to both the Royal Navy and the RNAS. His experiments in launching aircraft from capital ships was especially important and significantly contributed to the development of the Royal Navy’s first true aircraft carrier, HMS Argus, commissioned in September 1918.

But postwar service in an organization that offered little prospect for advancement had no appeal for Rutland, so in October 1923, after 22 years in the Royal Navy, he resigned his commission. His decision may have been influenced in equal measure by an offer he had received to advise the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and by the fact his marriage was disintegrating over his affair with a married woman. After divorcing his wife and marrying his mistress, Rutland moved his new wife and 6-year-old son from his first marriage to Japan, where he accepted a position with Mitsubishi Shipbuilding.

When anyone asked what he did for the company, Rutland explained he was helping the IJN construct shipborne aircraft-landing systems—a logical explanation for a man with his experience. Japan had been an ally of the United Kingdom and the United States during World War I, had a longstanding and close relationship with the Royal Navy and was very impressed with the role the RNAS had played during the war. Intent on building its own naval aviation capability, the Tokyo government hired several British aviation engineers and technical staff from Sopwith Aviation to assist in the design and construction of single-seat fighters and two-seater reconnaissance aircraft. Rutland was one of many aviation experts the Japanese hired to help them develop a naval air service.

Rutland worked in Japan until 1932, when he moved with his family across the Pacific to Los Angeles. There he founded the Rutland, Edwards & Co. stock brokerage firm, and in 1938 he established the Security Aircraft Co. in Santa Monica. Though he was apparently unaware of it, his work experience in Japan had prompted the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence to open a dossier on him. ONI soon concluded the retired British naval aviator was an agent working for Japanese military intelligence, that his aircraft company was actually a cover for his clandestine operations, and that his primary role was to help establish an espionage network in California. Its suspicions seemed confirmed when Security Aircraft Co. changed its name to Japan Aircraft Co., thus providing Japanese military officers cover to operate in the United States as civilian employees while gathering information on America’s military readiness.

Rutland’s espionage activities came to a crashing halt in June 1941 when the FBI arrested one of his contacts, IJN Lt. Cmdr. Itaru Tachibana, as the latter sought to collect information on the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Believing his cover was about to be blown and fearing for his life, Rutland asked the FBI for protection but was turned away. He then appealed to British authorities for help. Fearing that the arrest of a decorated British officer would generate a scandal, the United States sent him back to England in October 1941.

That December, shortly after the Japanese attacks on British and U.S. naval bases throughout the Pacific, the British interned Rutland as a collaborator under Defence Regulation 18B—a wartime statute that allowed for the indefinite detainment of British nationals suspected of enemy sympathies. Two prominent Royal Navy officers—Admiral of the Fleet Roger Keyes, 1st Baron Keyes of Zeebrugge and Dover, and Member of Parliament Commander Robert Tatton Bower—fought for Rutland’s release by challenging the legality of the Defence Regulation 18B to the House of Lords, but their efforts were ignored. Rutland remained incarcerated at London’s Brixton Prison and later on the Isle of Man until his release in late 1943. Rutland never returned to the United States, where his second wife and young children remained during the war and his internment. On Jan. 28, 1949, the disgraced World War I hero and aviation pioneer took his own life by inhaling gas.

Thomas Bradbeer, a retired U.S. Army field artillery officer, is an associate professor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. For further reading he recommends Rutland of Jutland, by Desmond Young; The Fighting at Jutland, by H.W. Fawcett and G.W.W. Hooper; and Japanese Intelligence in World War II, by Ken Kotani.