“For a period of more than three months after Pearl Harbor the American Volunteer Group was the pet and darling of the United States and the United Nations,” wrote Olga Greenlaw in her 1943 book The Lady and the Tigers. “The Flying Tigers, as captivated war correspondents insisted on calling them, were the hottest of the hot stuff.” And in those months, no Flying Tiger was hotter than “Scarsdale Jack,” as 2nd Pursuit Squadron leader Jack Newkirk came to be called.

Newkirk’s moniker was invented by war correspondents who flocked to Rangoon in January 1942 to cover the AVG’s valiant defense of Burma’s capital. At the time it was the one place in Asia where journalists could report on Allied victories against the seemingly invincible Japanese. When censorship rules precluded the use of pilots’ full names, reporters came up with nicknames. The first stories coming out of Rangoon mentioned “Slim from Scarsdale,” who eventually morphed into Scarsdale Jack.

Thanks to his widely reported exploits, Scarsdale Jack became so well known that in October 1942 Russell Wehlen wrote in The Flying Tigers, “When he was killed, millions of people in Britain, China and in his own land felt the loss of Jack Newkirk in their hearts.” Credited with seven victories and decorated by the British government, Newkirk was highly regarded by AVG commander Colonel Claire Lee Chennault. But questions later arose about Newkirk’s actions during his final mission, and there were even hints that he may have anticipated his death, adding a layer of mystery to Scarsdale Jack’s story.

John Van Kuren Newkirk was born in New York on October 15, 1913. An Eagle Scout, he gained a reputation as a marksman at age 10, when he shot a sheriff with a bow and arrow on a dare. After graduating from Scarsdale High School, he went on to Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, graduating in 1936. During his college years he was known for driving fast and wrecking cars. In 1938 he joined the U.S. Navy.

Newkirk was flying Brewster F2A-1 Buffaloes with VF-5 aboard the carrier Yorktown when he was recruited into the AVG as a flight leader at $650 a month. In July 1941, just days before boarding a ship for Burma, he married Virginia Jane Dunham of Lansing, Mich.

In November 1941, when the AVG’s three squadrons were formed, Newkirk was picked to lead the 2nd Pursuit Squadron, comprised mostly of Navy pilots, or “water boys.” Newkirk named the 2nd the “Panda Bears,” symbolizing the AVG’s Chinese mission—although some thought the sobriquet didn’t quite fit the hotshot fighter pilot image. The 1st Squadron was nicknamed “Adam and Eve” (after the “first pursuit”), and the 3rd’s pilots called themselves “Hell’s Angels.”

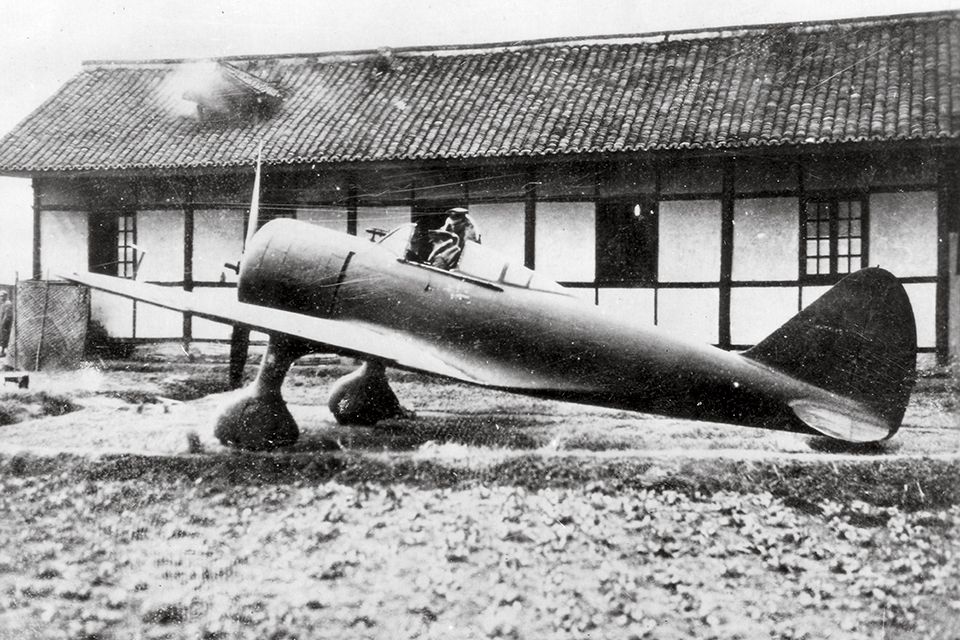

The AVG was still at Kyedaw airfield, its training base in central Burma, when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor on December 7, but its members would soon get a taste of action. On December 18, Chennault sent the 1st and 2nd squadrons to the AVG’s permanent base at Kunming, in southern China. The 3rd Squadron had already been dispatched to Rangoon to help Britain’s Royal Air Force defend the city against an anticipated Japanese onslaught. On the morning of December 20, Chennault’s Chinese warning net reported 10 Japanese bombers heading for Kunming from a base in Vietnam. Sixteen Curtiss P-40s of the 1st Squadron took off to intercept the Kawasaki Ki.48 “Lilys” south of the city. Eight 2nd Squadron P-40s followed them up, but were meant to stay close to Kunming, to serve as backup if any bombers got through. Newkirk led a four-plane flight to the northeast; the other four stayed over the city.

It was not a good day for the Panda Bear leader. The Japanese formation unexpectedly circled around the city, and an incredulous Newkirk suddenly found himself facing oncoming enemy bombers. This first sighting of the Japanese in a place they were not supposed to be caused the Panda Bears to hesitate—just briefly, but long enough to lose the advantage of surprise. The Japanese spotted the P-40s, jettisoned their bombs and turned away. Newkirk led his flight in a single pass—and the bombers were gone. They would not get far, however. The 1st Squadron caught up with them 30 miles southeast of the city, shooting down four and damaging most of the rest. Only one reportedly made it back to its base.

Newkirk was described as “black with anger” when he landed. Not only had his squadron failed to score (or so he thought), but he hadn’t even managed to get off one good burst. His guns had jammed. (Actually, Panda Bear Ed Rector was credited with shooting down the first Ki.48 that day. His aircraft had not been ready when the rest of the squadron took off, so he set out later on his own.)

Newkirk’s chance would come. The real action was in Rangoon. On December 23, more than 100 Japanese aircraft attacked the city. That Christmas Day they came back, 60 bombers and 25 fighters. During those two days the 3rd Squadron was credited with destroying 30 enemy aircraft, but lost five planes and two pilots, leaving it with only 10 flyable P-40s. On December 28, Chennault told Newkirk that the Panda Bears would replace the Hell’s Angels. The Pandas arrived at Rangoon’s Mingaladon airfield two days later with 17 P-40s. Newkirk was now in charge of the AVG’s defense of Rangoon.

The Panda Bears stayed on alert for the next three days, but all remained quiet. On January 3, 1942, Newkirk took the war to the Japanese, leading a flight of four from Mingaladon before dawn and heading for a Japanese airfield at Tak, Thailand, about 180 miles east. Jim Howard was on his wing, and behind were David “Tex” Hill and Allen Bert Christman. Christman developed engine trouble after takeoff and turned back, but the other three crossed the Salween River and the mountains. They could see Tak airfield as the sun rose.

Newkirk led the flight past the target, then turned to come back toward it out of the sun. Ahead of him, circling over the airfield, were a number of Nakajima Ki.27 “Nate” army fighters, while others taxied for takeoff below. Howard and Tex Hill dived on the field while Newkirk attacked the closest of two Nates and shot it down. A Ki.27 got on Howard’s tail, and Hill went after it. Almost simultaneously, another made an overhead pass at Hill. Newkirk got on that Nate’s tail, but the nimble Japanese fighter looped over and came back at him head-on. Both pilots blazed away at each other until the Japanese pilot pulled up. Newkirk saw pieces of his opponent’s plane falling before it spun off down to the jungle.

Newkirk would be credited with his first two kills that day. Hill also got one, while Howard destroyed four on the ground. It was a good start for the Pandas.

The next day, when 60 Japanese bombers escorted by Ki.27s came back to Rangoon, the Pandas claimed six bombers and eight fighters. On January 5, the Japanese arrived in the pre-dawn darkness, their first moonlight raid. They tried once again by day on January 6, coming in two waves: First 20 Nates engaged the Pandas, then the bombers arrived after the P-40s landed. The Pandas scrambled again, with the AVG claiming 18 bombers and two fighters that day. When the Japanese returned once more the following day, the Flying Tigers claimed eight fighters and five bombers.

Given their heavy losses, the Japanese opted to halt daylight bombing at that point. For more than two weeks they came only at night, mostly on nuisance raids. During that time the Panda Bears flew missions to Thailand by day.

On January 8, a flight led by Charlie Mott hit Mae Sot, leaving seven Japanese aircraft burning on the ground. Unfortunately, Mott himself was shot down and captured during the raid. The next day Newkirk led a flight back to Tak and destroyed two Nates on the ground.

The Pandas also flew escort missions. During one such sortie on January 20, while accompanying RAF Bristol Blenheim bombers to Mae Sot, the 2nd Squadron escort tangled with a group of Nates, and Newkirk was credited with downing two of them.

The Pandas were also taking losses, however. By that time one pilot had been killed and one captured, with four P-40s destroyed and seven damaged. Only 10 P-40s were flyable by January 12, when Chennault sent eight 1st Squadron P-40s to Rangoon to reinforce the 2nd Squadron.

Japan’s ground invasion of Burma started on January 20, when 18,000 troops flooded across the border from Thailand. By then the Japanese had also allocated more aircraft to the fight, and on the morning of January 23 they returned to Rangoon in force. Twenty Ki.27s struck that morning. Five Panda Bears went up and accounted for seven of the Nates, but a second wave of 30 bombers and 30 fighters came in just as the P-40s landed. Newkirk led 10 P-40s against the new threat, damaging one bomber, downing another and shooting a wing off a Nate that was harassing him. Then—with his P-40 heavily damaged—he landed hot, overshot the runway and crashed. He somehow walked away from the wreckage unhurt, having become the Pandas’ first ace.

From January 23 to 29, there were six major raids on Rangoon, each by as many as 100 bombers and fighters that came in waves, trying to catch the defenders on the ground. The official AVG score for those seven days was 49 enemy aircraft destroyed—including a Ki.27 by Newkirk on the 29th—but the Tigers lost two P-40s, while the RAF lost 10 planes and their pilots. Tens of thousands of Rangoon residents had fled by that time, and order had completely broken down in the city and most of the surrounding countryside.

On January 25, Chennault sent 12 Adam and Eve P-40s to Rangoon, ordering Newkirk to bring the Panda Bears back to Kunming. But the Japanese just kept coming, so the Pandas kept flying. Most of the 2nd Squadron finally left Rangoon on February 3, though Newkirk lingered. On February 7, 1st Squadron leader Robert J. Sandell was killed while testing a plane. Robert H. Neale replaced him.

Newkirk departed Rangoon on February 10, reaching Kunming via India. When he finally showed up, he was clearly exhausted. But Chennault sent him right back to Rangoon “with a special message,” according to Olga Greenlaw, who kept the AVG’s war diary. After Newkirk returned, he fell asleep while telling Greenlaw about flying a ground support mission along the Sittang. He had been in almost continuous combat for well over a month.

Rangoon fell on March 6, a few days after the remaining P-40s were moved to Magwe, in central Burma, where operations continued against the Japanese. On March 21, the Japanese Army Air Force struck back, pounding Magwe for more than 24 hours. All the AVG’s P-40s at the field were hit, and most of the RAF’s remaining Hawker Hurricanes and Blenheim bombers were destroyed.

Back at Kunming, Chennault called in Newkirk and Bob Neale early on March 22 to discuss a plan to strike back. One of the bases for the aircraft that attacked Magwe was deep inside Japanese-controlled territory at Chiang Mai, in north Thailand. With the AVG bases in Burma gone, it was beyond the P-40s’ range, so the Flying Tigers would not be expected. Chennault’s plan called for the raiders to fly via Loiwing, China, refuel there and continue on to a small RAF airstrip at Namsang in Burma, within easy range of Chiang Mai. After spending the night, they would strike Chiang Mai the next morning.

Chennault also identified a second target—a smaller Japanese air base at Lampang, about 45 miles southeast of Chiang Mai. Neale would serve as the overall commander of the mission, leading six P-40s to Chiang Mai. Newkirk would take four P-40s to strike Lampang, then rejoin Neale’s flight at Chiang Mai.

The 10 P-40s took off from Kunming at noon on March 22. As Neale had never been to Loiwing, Newkirk was to lead the flight. In his memoir A Flying Tiger’s Diary, Charlie Bond wrote that after takeoff, “We wandered all over the sky until we hit the Salween River. At this point Jack turned south when he should have turned north.” Convinced that Newkirk was headed in the wrong direction, Bond tried to get him to turn north. But when Newkirk continued flying south, Bond joined Neale and William E. Bartling and flew on to Loiwing. Newkirk and the rest showed up at Loiwing later, well behind schedule. The flight to Namsang was postponed until the next day.

Dawn on March 23 brought fog, rain and a low ceiling. Takeoff was delayed until 1500 hours so that the P-40s would arrive at Namsang near sundown, when the Japanese fighter threat was low. The P-40s landed at sundown, and the pilots refueled their aircraft in the dark.

A small incident that evening involving Newkirk has since become part of AVG lore. The Flying Tigers were using the RAF’s bamboo hut washroom when a British sergeant warned them that the water was polluted. This apparently made an impression on everyone but Newkirk, who went on to brush his teeth using the water. When Gregory Boyington asked him if he had heard the sergeant’s warning, Newkirk smiled and said, “Well, after tomorrow I don’t think it’ll make any difference.”

Recommended for you

Years later, Boyington recounted the incident in his book Baa Baa Black Sheep, also commenting on Newkirk’s behavior the previous evening in the clubhouse at Loiwing. Everyone had apparently had a good time—except Newkirk. To Boyington, Newkirk seemed “different” that evening, not the same guy he had known on shore leave and flown with in Rangoon. “Previously always an affable gent,” he wrote, “but this night he just didn’t want to talk at all—about anything.” Boyington wondered whether Newkirk had “gotten the word,” a phrase he said “referred to people who had a feeling that they are not going to live through something.”

After dinner in Namsang’s RAF mess, the pilots made a final review of plans for the raid. Takeoff was set for 0600 hours the next morning. Neale’s six P-40s would leave first, followed by Newkirk’s four. The two flights were to rendezvous over the field at 10,000 feet, and Neale would then lead both flights to Chiang Mai, where Newkirk would break off and take his flight to Lampang. If he found no aircraft there, he was to turn back and join the attack on Chiang Mai.

The planned rendezvous over the field never happened the next day. In his report, Neale wrote that by 0630 his six aircraft had joined up, but “due to low visibility,” he could not find Newkirk’s flight, “so proceeded on a course of 150 true for the objective.” Rector, flying behind Neale, later wrote that their flight climbed to the “predetermined rendezvous altitude of 10,000 feet,” then circled the field for 20 minutes waiting for Newkirk. But Newkirk’s flight did not show up, “probably due to bad visibility,” Rector speculated.

Frank Lawlor, who led the second of the two elements in Newkirk’s flight, wrote in his combat report that after takeoff from Namsang he rendezvoused with the other three P-40s in Newkirk’s flight, and “when the formation had reached an altitude of 6,000 feet we headed on course 150.” Neither he nor Newkirk’s wingman, Henry M. Geselbracht, mentioned a missed rendezvous. It was as if the two flights were following different scenarios.

The differences between what had been planned and what actually happened became even more striking as the two flights continued on their separate paths to their targets. Neale’s six aircraft headed for Chiang Mai. Visibility was poor. The sun was not yet up, and there was ground haze as well as smoke. Charlie Bond, flying on Neale’s wing, was the only one who had flown over the area before. He watched the elapsed time and spotted the mountain that overlooks the airfield, then gave a prearranged signal to Neale and led the attack.

Four P-40s dived down, while two others—Rector’s and William “Black Mac” McGarry’s—flew top cover. Most of the 40 or more Japanese aircraft on the field were parked in two long rows. As the Flying Tigers started strafing, they could see props turning. Despite intense anti-aircraft fire, three of the Americans made two passes. Bond had made four and was starting a fifth when he realized the groundfire was getting too hot. Looking back as he climbed away, Bond recalled, “the entire airfield seemed to be in flames.” He was convinced the Tigers had destroyed “at least 25 or 30” of the Japanese aircraft (the official AVG tally would be 15). On the way back to Burma, McGarry was forced to bail out when his P-40 started trailing smoke and losing altitude. (After wandering in the jungle for three weeks, Black Mac was captured and taken to a Bangkok compound, but escaped in April 1945 with the help of Free Thai operatives.)

Newkirk’s P-40s had reached the eastern side of Chiang Mai at 0710. Bond noted that Newkirk’s flight arrived at Chiang Mai “a few minutes ahead of us,” then added, “For some reason or other, while flying down to attack Lampang, they decided to strafe the Chiang Mai railroad depot.” That alerted the Japanese at the airfield, who were already manning anti-aircraft guns and trying to get their fighters in the air when Neale’s flight arrived. “After strafing the railroad depot,” Lawlor wrote, “we continued south to Lambhan [Lawlor’s spelling].”

Lampang, Newkirk’s intended target, is about 45 miles southeast of Chiang Mai. In 1942 a single road and a railroad line connected the two cities. About 15 miles south of Chiang Mai, along the same road and rail line, is the small town of Lamphun. The similarity of those place names and variations in their English language spellings in the mission combat reports of “Lambhun,” “Lambohn” and “Lambahn” may have confused Newkirk and others. Whatever the cause, it’s apparent from a close reading of after-action reports that Newkirk’s flight never got as far south as its intended target at Lampang.

As they flew along the railway just south of Chiang Mai, the AVG pilots spotted a row of about 15 warehouses. All four pilots strafed them, setting some of the structures on fire. The flight continued south, approaching “Lambhan,” according to Lawlor, and making a wide circle. He reported: “We flew over two small satellite fields, but no airplanes. A third and larger field also had no planes, but the area surrounding the field had several barracks.” The Tigers strafed the barracks, but then Newkirk turned north, back toward Chiang Mai, instead of continuing south toward the city of Lampang.

Geselbracht, flying on Newkirk’s wing, later described what happened after that: “The next target we dove on were two vehicles on the road south of Chiang Mai. Newkirk dove and fired and as he cleared the target I began to fire. I saw a flash of flame beyond the target and looked for Newkirk after my run. I realized he had crashed causing the flash.” Geselbracht also noted: “The two vehicles we fired at, I believe were armored cars. They were camouflage brown and were squarish in appearance. I believe at least one was destroyed.”

At the rear of the flight, when Robert “Buster” Keeton looked down and saw a ball of fire roll along the ground, it took him a moment to realize that it was Newkirk’s plane. Keeton had no way of knowing whether Newkirk had been hit by groundfire or just never pulled out of a dive on a vehicle that looked to him like a weapons carrier.

Lawlor may have had the best view of what happened: “Immediately after leaving the area of the barracks, Squadron Leader Newkirk headed back up the road to Chiang Mai. He went into a dive to strafe what appeared to be an armored car and I saw his plane crash and burn. Since by this time visibility had improved considerably and there appeared to be no unusual circumstances it was evident that Newkirk had been hit by enemy fire, possibly from the armored car.”

Lawlor then took command of the flight—per Newkirk’s previous instructions, if anything happened to him. He led the other two P-40s back toward Chiang Mai, and they encountered extremely heavy antiaircraft fire as they neared the city. Approaching at about 2,500 feet, Lawlor stayed to the east of the city and kept the flight heading north. They could see the Chiang Mai airfield clearly now, where Lawlor noted “several large fires were burning.” Once clear of the area, they turned west, on a heading that would take them to the small British auxiliary field at He Ho, Burma. They landed there at 0835 and refueled before heading back to Loiwing. Neale’s flight refueled at Namsang, then continued on to Loiwing.

This is where the story of Scarsdale Jack Newkirk usually ends. More than 50 years later, however, another piece of the story emerged in North Thailand. In November 1994, a group of Flying Tigers Association members visited there, among them Chiang Mai raiders Bond, Rector and Keeton. They were there to see the remains of Black Mac McGarry’s P-40, one of the two AVG aircraft that went down during the March 1942 raid. Discovered by tribal hunters in 1991, the wreckage had been extracted from the jungle by Thailand’s Foundation for the Preservation and Development of Thai Aircraft and moved to a hangar at the Royal Thai Air Force base at Chiang Mai.

Once the wreckage of McGarry’s P-40 was identified as an AVG plane, a new effort was launched to locate the remains of Newkirk’s P-40. By 1994, when the former AVG pilots visited, five Thai witnesses to his crash had been found and interviewed. Two had been students at the Buddhist temple that stood at the site of the crash, just east of Lamphun, and the other three were the children of local farmers. All five told a similar story. They saw the aircraft as it approached and then crashed. No one recalled seeing more than one plane, nor did they see any armored vehicles on the road that morning, although they said there could have been.

The plane they saw came from the southeast, and seemed to be following the railroad tracks from Lampang. The Kuang River flows along Lamphun’s eastern edge, between the tracks and town. The railroad stays on the far side of the river until it reaches the northern end of Lamphun, where it crosses a bridge and turns north toward Chiang Mai. In early 1942, anti-aircraft guns were positioned on a riverbank at the crossing. Those guns were manned on March 24, and it seems likely the gun crew had been alerted that enemy aircraft were nearby.

As the aircraft approached Lamphun from the southeast, it stayed east of the railroad and the river, flying low. When it reached the railroad bridge the anti-aircraft guns opened fire, and the plane started a wide turn that took it first to the west, then back to the south. It was still turning when it reached the southern edge of town, headed east and recrossed the Kuang River. At that point the aircraft fired its guns and struck a man in an oxcart, killing both driver and ox.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

The plane headed toward a field just east of the river, where in 1942 a Buddhist temple stood. The aircraft was very low as it approached from the south, and one of its wings struck a large tree growing near the temple, sending the plane crashing into the field. Torn from the fuselage by the impact, the engine was hurled almost up to the railroad embankment, far beyond where the rest of the aircraft came to rest.

Locals found the pilot’s body near the plane, wearing a partially opened parachute. He had been thrown from the cockpit and appeared to have been killed instantly. Some witnesses thought he might have been trying to bail out, but others believed the chute had likely been torn from its pack when the aircraft struck the tree.

The pilot was buried near a grove of trees at the far side of the field. The plane’s wreckage was piled on a truck and hauled off to a local police station, where it was photographed for the newspapers. Some time later, the witnesses said, “officials” came, disinterred the pilot’s body and took it away. But none of the five witnesses could say whether those officials were Japanese or Thai, and their recollections about just when that happened were dim.

After more than half a century, some of the details the five witnesses recalled may be open to question. But what is certain is that on March 24, 1942, Newkirk crashed into the field in front of the small temple, and that he was buried there. His body was, in fact, later disinterred. In May 1949, Scarsdale Jack came home.

An item in The New York Times, datelined Scarsdale, N.Y., May 1, 1949, stated that John Van Kuren Newkirk, “who was known as ‘Scarsdale Jack’ while fighting with the American volunteer air squadron in Burma, was buried here this afternoon in the yard of the Protestant Episcopal Church of St. James the Less….He was killed on March 24, 1942 at Chiang Mai, Thailand, and recently his body was brought to this country.” His grave marker bears the inscription, “Until I have done all in my power I shall not return.” It echoes a line he wrote to his wife when the battle was just beginning: “I can’t leave until this job is finished.”

Bob Bergin is a former U.S. Foreign Service officer. For additional reading, he recommends: A Flying Tiger’s Diary, by Maj. Gen. Charles R. Bond and Terry H. Anderson; and Tex Hill, Flying Tiger, by David Lee “Tex” Hill with Major Reagan Schaupp. Also see flyingtigersavg.com.

This feature was originally published in the July 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.