The Fairchild XC-120 “Pack plane” featured an intriguing modular transport design that never achieved full maturity.

Fairchild’s C-119 was one of the most utilitarian military cargo planes of the post-World War II era. First flown in 1947 and unofficially known as the “Flying Boxcar,” it featured a large and capacious fuselage suspended from a twin-boom airframe. More than 1,100 C-119s were built, and they served in a variety of roles with great success in both the Korean and Vietnam wars.

The engineers at Fairchild who developed the C-119 believed there was untapped potential in the design. Military transport aircraft were equipped to perform a variety of different missions, including transporting personnel, carrying cargo, delivering paratroopers and dropping bulky loads by parachute. The fuselage had to be outfitted with the appropriate features to permit the performance of all those tasks, which meant having to carry additional weight that might not necessarily contribute to the specific mission at hand. The Fairchild engineers reasoned that a military cargo plane would be more efficient if it was equipped solely for the specific mission it was performing, and that the best way to accomplish that was for it to carry a different, specialized fuselage for each particular mission. They also regarded their C-119 as an ideal basis from which to develop such an aircraft.

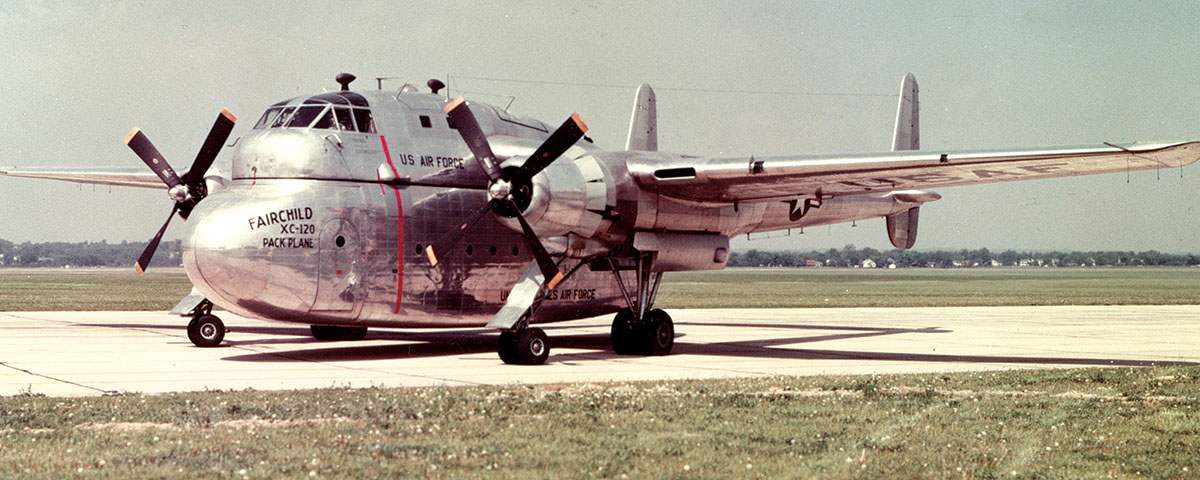

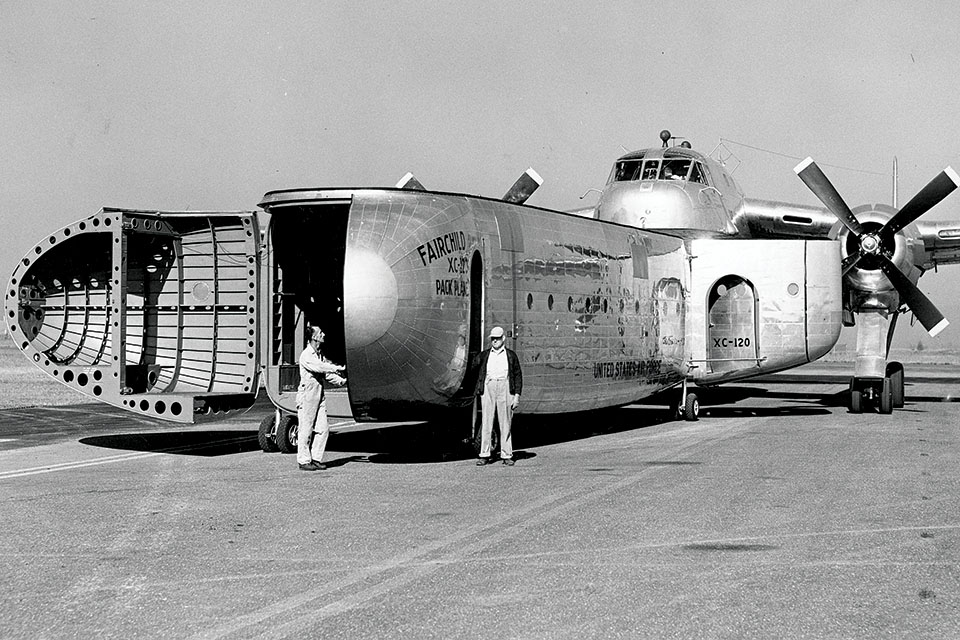

Thus was born one of the most unusual transports to ever take to the air, the XC-120 “Pack Plane.” It retained the C-119’s twin-boom configuration, but with an entirely new, drastically reduced central fuselage. The new fuselage had a flat bottom to which a variety of specialized cargo pods could be attached, depending upon the mission. For instance, one pod could be optimized for the carriage of heavy cargo, while another could be set up for personnel. Other cargo pods could be configured for the delivery of troops or heavy equipment by parachute. Still others could serve as portable hospitals, radar stations, command centers or perform other specialized functions.

One major change in the design involved replacing the C-119’s tricycle landing gear with an entirely new four-wheel undercarriage, with all four components built into the twin booms. The aircraft’s ground clearance could be adjusted by raising or lowering the height of the landing gear, thus easily accommodating different-sized cargo pods. The cargo pod itself was supported on four small wheels of its own, so it could be easily maneuvered on the ground independent of the aircraft. Once positioned underneath the fuselage, the pod was raised into position by electric winches built into the four corners of the fuselage, and then locked into place with ball-and-socket joints. The seam between fuselage and pod was then sealed by means of an inflatable gasket.

The XC-120 was intended to be deployed to forward landing fields, where it would quickly deposit its pod and take off again. This greatly reduced the loiter time on the ground, when the airplane was most vulnerable while it was laboriously unloaded. Then, while the forward ground personnel were unloading the pod, the Pack Plane would make another trip to retrieve a new pod. On its return to the forward base, the plane would drop off the new pod and return home with the emptied one.

As often seems to be the case with unusual postwar designs like this, it turns out the Germans came up with a similar concept during World War II. Like the XC-120, the Fieseler Fi-333 was designed to transport modular cargo containers. The German design was more awkward, however, featuring a long, slender fuselage fitted with a fixed tailwheel undercarriage, and its proposed cargo pods would have been considerably smaller than the Pack Plane’s. In any case, the Fi-333 never got beyond the drawing board, and remained nothing more than a design project.

In many ways the XC-120 was very similar in concept to that of the modern shipborne intermodal cargo container, which has almost completely taken over the international cargo transportation business. But while the Pack Plane flew for the first time on August 11, 1950, the maiden voyage of the first container ship did not occur until April 1956.

The XC-120 had a wingspan of 109 feet and an 82-foot fuselage. The prototype’s maximum gross weight was 64,000 pounds, including a 20,000-pound cargo capacity. Operated by a five-man crew, the aircraft was powered by two 3,250-hp Pratt & Whitney R-4360 radial engines and had a top speed of 258 mph.

The XC-120 was tested extensively during 1950, and was widely publicized in the media of the day. In spite of its innovative design, however, in the end the U.S. Air Force did not accept it. Although it flew well with a cargo pod attached, the aircraft proved to be unstable without it. This phenomenon was specifically attested to by James Winnie, who served as flight engineer during the plane’s test flights at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida. “Glad they only made one,” was his terse comment.

Given time the stability problem might have been sorted out, but the outbreak of the Korean War, and the consequent need for increased C-119 production, seems to have put an end to Fairchild’s development of the Pack Plane. Nevertheless, the XC-120 remains an intriguing aviation concept that was ahead of its time in 1950, and may still be so today.

This article originally appeared in the September 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!