Three months after World War II ended, five military planes took off from Fort LauderdaleHollywood Naval Air Station in Florida and vanished somewhere over the Atlantic in the area known as the Bermuda Triangle. For more than 50 years, military and civilian experts have tried to find an explanation for their disappearance.

On December 5, 1945, the Fort Lauderdale/Hollywood airport was a bustling naval air station, where war-weary veterans waited for their discharge papers. For servicemen on the sprawling base, it was just another day of business as usual.

Marine Corporal Allen Kosner, Sergeant Robert Gallivan and Private First Class Robert Gruebel had just eaten lunch and were on their way back to the barracks. They were scheduled for an afternoon training flight but did not have to report for another hour. As the three Marines strolled from the mess hall they talked about their forthcoming holiday plans and decided to attend the base theater that evening to see What Next, Corporal Hargrove? starring Robert Walker and Keenan Wynn.

It was an exciting day for Robert Gallivan. Four years had passed since he had enlisted, and he had recently completed 18 months of combat duty in the South Pacific. This day would mark his last flight as an aerial gunner. He was scheduled to be discharged the next day and would be on his way home to Northampton, Mass.

Robert Gruebel was also in high spirits, even though he still had three more years before his enlistment expired. Gruebel was happy just knowing he would soon be in the air again. Although his enthusiasm for flying was insatiable, Gruebel did not plan a career in aviation. Upon leaving the Marines he intended to become a priest. He had written his parents in Long Island, N.Y., to say he would be home in time to attend Christmas Mass.

The men rested in their rooms until it was time for their preflight briefing. As Allen Kosner rose from his bunk, he suddenly decided not to go on the mission. He had already logged his required monthly time and had no difficulty getting excused. Kosner could not have known that during the next few hours a sequence of strange events would take five airplanes and 14 men on a course to oblivion.

At 1 p.m. the officers and enlisted men of Flight 19 waited impatiently in the Operations building. Four pilots were being checked out that day in TBM Avenger bombers by an instructor who would be joining them on the flight, while nine enlisted men were taking advanced combat aircrew training. The takeoff was set for 1:45, but everyone knew they would not leave on time. Their instructor had not yet arrived.

The TBM Avenger earned a reputation during World War II as the most deadly torpedo bomber ever built. Avengers had two designations, depending upon who made them–those constructed by Grumman Aircraft Corporation were called TBFs, and the General Motors version was known as the TBM.

Regardless of which plant they came from, Avengers lived up to their name while operating from both land bases and aircraft carriers. They began service in the spring of 1942 and were responsible for sinking the Japanese battleship Yamato, her escort of four destroyers and the cruiser Yahagi.

The Avenger’s wingspan was 54 feet. Its Wright Cyclone R-2600 engine developed 1,600 horsepower, giving the plane a top speed close to 300 miles per hour for 1,000 miles. The Avenger carried one standard torpedo or a 2,000-pound bomb. Armament included a .50-caliber machine gun under the forward cowl and another in a power-operated ball turret behind the cockpit. Each plane had a three-man crew–pilot, gunner and radioman.

Their instructor, Lieutenant Charles C. Taylor, arrived at the briefing room at 1:15 p.m. and went to the duty officer. Instead of offering an apology for being late, he asked to be relieved. Taylor gave no reason other than saying, ‘I just don’t want to take this one out. He was informed that no other instructors were available.

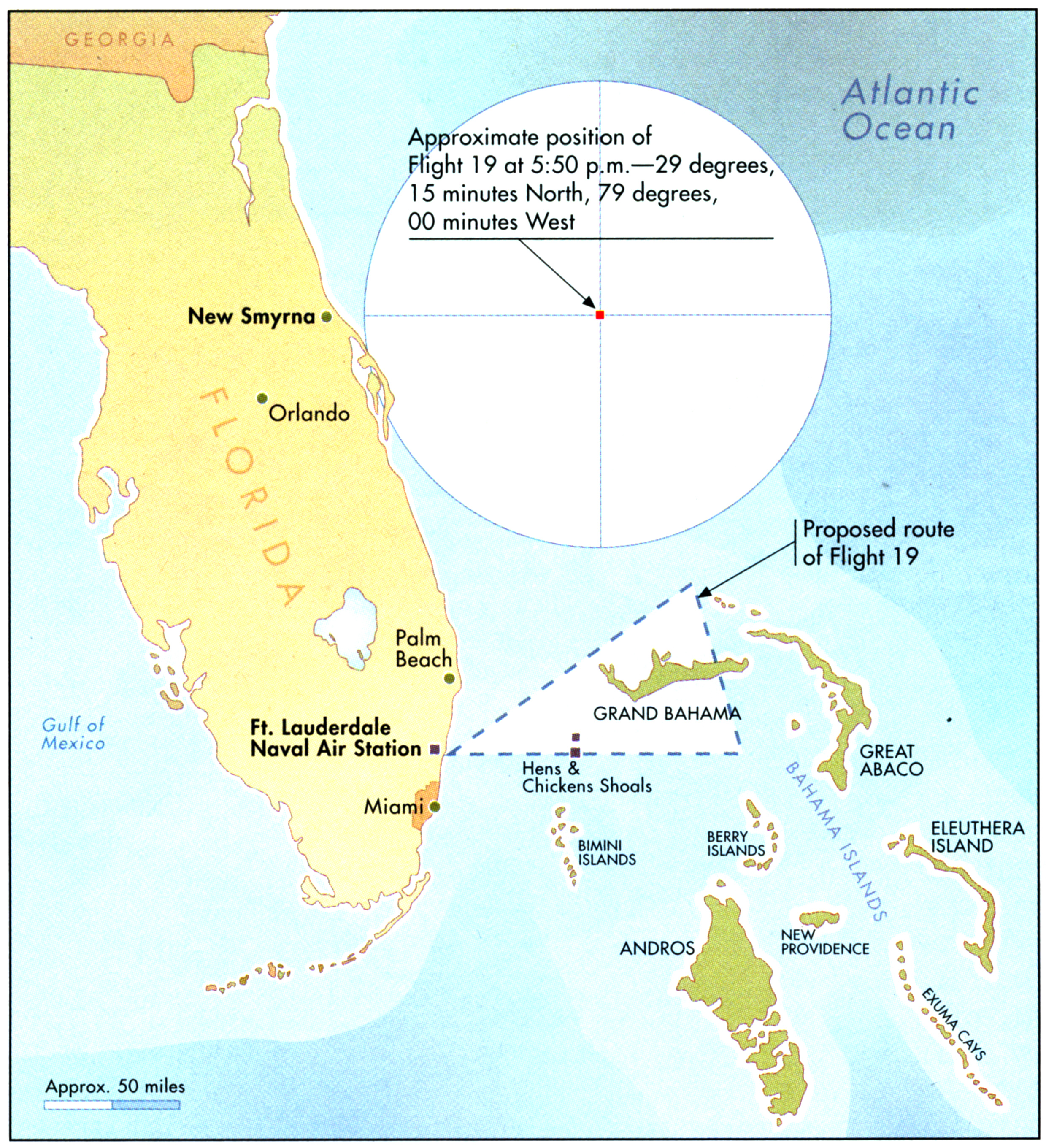

Contrary to most accounts of Flight 19, it was not a patrol but a training flight, Navigation Problem Number One. The men would leave Fort Lauderdale and fly a course of 091 degrees for 56 miles, then practice low-level bombing at Hens and Chicken Shoals. Afterward, they would continue on the same course another 67 miles to complete the first leg. The second leg of the flight would take them 73 miles northwest, on a heading of 346 degrees. Finally, they would turn left to 241 degrees, a course that would bring them 120 miles back to the air station. It was a routine pattern, to be flown within the mysterious area known as the Bermuda Triangle.

Flight 19 was supposed to be the final hop for the four pilots, who had already completed two similar exercises in the same area. Although they were students, all were qualified naval aviators, each with an average of 300 hours’ flight time.

Lieutenant Taylor, 27, was a six-year Navy veteran with more than 2,000 hours in his logbook. After attending Texas A&M University, he had become an aviation cadet. Upon receiving his wings, he joined Air Group 7 aboard USS Hancock. In January 1945 Taylor became a flight instructor in Miami–relatively peaceful duty after serving 10 months flying combat missions in the South Pacific.

The students analyzed weather charts and winds aloft. Between 3,000 and 4,000 feet, Flight 19 would find broken clouds with visibility 8 to 10 miles. At 4 p.m. they could expect scattered rain showers and thick clouds.

Lieutenant Taylor was to fly in the lead plane, whose radio call sign was FT-28. With him were Walter R. Parpart and George F. Devlin.

Captain Edward J. Powers, Jr., 26 years old, was flying FT-36 with Howell O. Thompson and George R. Paonessa. Powers had entered the Marine Corps after graduating from Princeton. He was the only married man in Flight 19.

Second Lieutenant Forrest J. Gerber, 24, would fly FT-81 with William E. Lightfoot. Gerber had received his commission and gold wings four months earlier. (Allen Kosner would have flown in this plane had he not opted out.)

Captain George W. Stivers would fly FT-117 with Robert F. Gallivan and Robert F. Gruebel. The 25-year-old pilot had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, then served as a combat officer for two years in the South Pacific before applying for flight school.

Ensign Joseph T. Bossi was in FT-3 with Herman A. Thelander and Burt E. Baluk. Bossi had attended the University of Kansas before enlisting as an aviation cadet. He planned to be home with his parents on Christmas Day–which would also be his 21st birthday.

Taylor took off at 2 p.m., and 10 minutes later the other four TBMs were in formation beside him. Despite a delay, Flight 19 was finally on its way, carrying 14 men on a journey destined to end in one of the most baffling mysteries of naval aviation.

At 2:30 they arrived over an area commonly known as Chicken Shoals, about 22 miles north of Bimini in the Bahamas. The pilots took turns making low-level passes and releasing bombs on an old concrete hulk.

At 3:00 the flight left the target area to fly another 67 miles on the same course and complete the first leg. A fishing boat skipper gazing skyward saw the planes heading east at that point. He was apparently the last person to see the ill-fated flight.

Lieutenant Robert F. Bob Cox was flying over Fort Lauderdale with a group of students 40 minutes later when he heard a signal that he thought was from a boat or plane in distress. A voice was coming in on 4,805 kilocycles and talking to someone named Powers. The anxious speaker provided no identification but repeatedly asked Powers what his compasses were showing, then said, We must have got lost after that last turn. Five minutes later, Cox called Operations at Fort Lauderdale and told them what he had heard. They acknowledged and alerted Air Sea Rescue Task Unit 4 at Port Everglades.

Lieutenant Cox then tried to find out who was in trouble. This is FT-74, Cox radioed. Plane or boat calling Powers, please identify yourself so someone can help you. There was no answer.

At 4:05 radioman Rolland J. Koch, in Fort Lauderdale’s control tower, heard about the TBMs in trouble and sounded the alarm. Seven minutes later, Cox tried to contact Taylor, Flight 19’s instructor. This is FT-74, he radioed. What is your trouble? He received no reply but kept trying to radio Taylor.

Taylor finally answered him at 4:21. This is FT-28, Taylor said. Both my compasses are out and I’m trying to find Fort Lauderdale. I’m over land, but it’s broken. I’m sure I’m in the Keys, but I don’t know how far down.

Cox thought it odd that both of Taylor’s compasses should be out of commission at the same time, and he was concerned about the nervous tone in Taylor’s voice. Put the sun on your port [left] wing if you’re in the Keys and fly up the coast until you get to Miami, Cox told him. Then Fort Lauderdale is 20 miles farther. What is your position? I’ll fly south and meet you. Taylor responded, I know where I am now. I’m at 2,300 feet. Don’t come after me.

FT-28, Roger, Cox said. You’re at 2,300 feet. I’m coming to meet you anyhow.

Moments later, Taylor said, We have just passed over a small island. We have no other land in sight. Cox could not understand why Taylor was unable to see other islands as well as the Florida peninsula if he was really over the Keys.

Taylor called again. Can you have Miami or someone turn on their radar and pick us up? he asked Cox. We don’t seem to be getting far. We were out on a navigation hop, and on the second leg I thought they were going wrong. I took over and was flying them back to the right position. But I’m sure that neither one of my compasses is working.

Turn on your emergency IFF gear, or do you have it on? Cox radioed. The Identification Friend or Foe transponder was used by ground stations to identify aircraft. Taylor said he did not have his IFF on. Cox suggested he use his ZBX homing receiver, but he received no answer.

Cox passed along Taylor’s request for assistance to radar stations in the area. Merchant vessels were alerted to the situation, and the Coast Guard prepared to launch search aircraft. The control tower at Fort Lauderdale never maintained radio contact with overwater flights but could monitor the pilots’ conversations. All radio contact with the lost TBMs was handled by Air Sea Rescue Task Unit 4 at Port Everglades, about a mile from the naval air station.

At 4:25 Stivers, in FT-117, radioed: We are not sure where we are. We think we must be 225 miles east of base. There were a few seconds of static, and then he continued, It looks like we are entering white water.

We’re completely lost, another Flight 19 pilot radioed.

At 4:28 Cox called Taylor again. He received no reply but heard Taylor and his students discussing their estimated position and compass problems.

Taylor was ignoring all of the standard procedures that were drummed into students during classroom lectures throughout the course. In case of disorientation, a pilot was supposed to turn on the IFF, climb for altitude, and try to pick up the homing transmitter from the air station. He would tune to 3,000 kilocycles. If he was over water he was supposed to fly toward the west; if he was over land, he was to fly east.

Cox then began to have problems of his own. A relay burned out in his radio, and he was no longer able to communicate with anyone. He tried all frequencies but heard only silence as he banked his plane toward the air station.

After landing, he went to the duty officer to report on the worrisome situation. I know where the planes are, Cox said. I’d like to take the ready-plane out and lead them back to base.

Very definitely no, said Lt. Cmdr. Don Poole, who was expecting a position fix on the TBMs. He told Cox to wait. Unfortunately the fix was delayed, and the ready-plane never left the ground.

Radioman Melvin Baker and two assistants were on duty at Air Sea Rescue Task Unit 4. They had been monitoring conversations from Flight 19 since the first indication of trouble. At 5:07 Baker heard Taylor tell his students: All planes in this flight join up in close formation. Let’s turn and fly east. We are going too far north instead of east.

Two students objected to the course change. If we’d just fly west, we would get home, said one pilot. Head west, dammit! said another exasperated airman.

Still unsure of his location, Taylor remained on his eastbound heading for only eight minutes, then called Port Everglades at 5:15. I receive you very weak, said Taylor. We are now flying 270 degrees. We will fly 270 until we hit the beach or run out of gas.

Baker urged Taylor to change to 3,000 kilocycles, the emergency channel, but Taylor said he must keep his planes together and could not change frequencies. Communications on 3,000 kilocycles were clear and static-free, while signals on 4,805 kilocycles were weak and garbled.

When Flight 19 had less than two hours’ flying time until the planes exhausted their fuel supplies, Taylor described a large island he had just seen during a break in the cloud cover. Baker was sure the Avengers were over Andros Island, the largest in the Bahamas. Baker gave Taylor a heading that would take him to Fort Lauderdale. Once Flight 19 assumed the new course, Taylor’s voice kept coming in stronger over the radio as the TBMs approached Florida.

But after flying his western heading for a few minutes, Taylor suddenly changed his mind again at 6:09. For some reason, he did not believe he was going in the right direction. It was apparently at this time the instructor made a decision that would seal Flight 19’s fate. Taylor told Powers in FT-36: We didn’t go far enough east. Turn around again and go east. We should have a better chance of being picked up closer to shore.

Taylor was so confused that he still could not decide whether he was over the Gulf of Mexico or the Atlantic Ocean. He erroneously concluded he was over the Gulf. Taylor’s transmissions began to weaken as he continued flying eastward, out of radio range.

Radioman Baker heard Taylor say: All planes, close up tight. Will have to ditch unless landfall. When the first plane drops to 10 gallons, we all go down together.

Later analysis revealed that one of the pilots in Flight 19 apparently realized an eastbound heading would only take them farther out to sea. That man–it is unclear which one–defied regulations, broke away from the formation and started flying west toward the coast.

The network of direction-finding stations finally obtained a reliable single-bearing fix on Flight 19 at 5:50 p.m. But two bearings were needed to pinpoint the Avengers. Two PBM Mariner seaplanes were sent to investigate the area where Flight 19 might be found. One of the PBMs exploded and crashed 23 minutes after takeoff, killing all 13 men aboard. Merchant seamen on the oil tanker Gaines Mill saw the Mariner explode and fall into the sea. Confirmation of this unfortunate accident came from radar operators aboard the aircraft carrier USS Solomons. They looked for survivors but found only twisted debris in the rough seas. There was no extensive investigation of the explosion.

What caused the PBM to explode in midair? Some have speculated it was a crewmen smoking tobacco. Anyone assigned to PBMs was aware that the nickname for the Mariner was the flying gas tank. Smoking restrictions were posted in all PBMs and as a rule were strictly enforced. But it is possible that a crewman ignored the regulations. If the planes of Flight 19 ditched at sea on that night, they faced nearly insuperable odds. The weather conditions were against them. It was a cloudy, dark, moonless night. The merchant ship Viscount Empire reported tremendous seas and winds of high velocity.

At 7:04 the tower at Opa Locka picked up a faint transmission: FT…FT…. It was part of the call sign used by Flight 19, and it seemed to be coming from one of the lost pilots. It was the last message received from the doomed flight.

A rescue boat patrolling the waters off Miami called Port Everglades at 8:13 and said they had been unable to contact the missing planes. They were told to secure for the night. The Avengers’ fuel supply would have been exhausted at 8 o’clock.

Just before midnight, Joan Powers, the wife of Captain Edward Powers, who had been piloting FT-36, awoke in her apartment in Mount Vernon, N.Y., suddenly overcome by an overpowering fear that something terrible had happened to her husband. Unable to shake her fear, she called the operations officer at Fort Lauderdale, asking to speak to her husband. She was told he could not be reached.

A massive search effort was launched the following morning. Searchers based their efforts on the direction-finding fix as well as the maximum distance the planes could have flown before they ran out of fuel.

Search operations continued for five days and included the whole state of Florida, extending north into Georgia and south through the Keys. More than 200,000 square miles of the Atlantic Ocean were crisscrossed by searchers, as well as the Gulf of Mexico. No trace of the Avengers was found.

An official hearing was ordered by Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal, and a board of investigation met in Miami on December 10, 1945. The board members were completely baffled. It seemed inconceivable that a highly experienced instructor such as Charles Taylor could lose a grip on his general position and become so confused that he was unable to reorient himself and lead his flight back to Fort Lauderdale. The board concluded, The five TBMs and naval personnel disappeared as a result of causes or reasons unknown after having taken off on a routine navigational flight out of Fort Lauderdale on 5 December 1945.

The Navy Department offered no explanation for Flight 19’s disappearance or the fate of the 14 men aboard the TBMs. But testimony at the hearing provided some interesting facts that should be subjected to further scrutiny. An incredible string of unusual coincidences had taken place on the afternoon of December 5.

Flight 19 was Lieutenant Taylor’s first assignment since his arrival at Fort Lauderdale. He had been transferred from Miami in November, but he had led no navigation hops until he commanded Flight 19. Could Taylor’s lack of aviation experience in the Fort Lauderdale area have played a part in the tragedy?

Lieutenant Cox, who was instructing another group of students on a flight that same afternoon, experienced radio problems at a time when he might have been able to locate Flight 19. But shortly after Cox contacted Taylor, his transmitters failed, preventing further communication with the missing planes.

Unusual difficulties plagued every rescue effort throughout the afternoon of December 5. Radio reception between Florida and the TBMs was intermittent at all times. And communications were further impeded because transmissions from Cuban broadcast stations interfered with reception.

After Flight 19 turned onto the second leg of the flight, weather played a cruel trick on the unsuspecting pilots. A secondary cold front was sweeping across the Florida mainland, bringing heavy clouds, rain showers and gusty winds. Conditions had clearly changed in the interval since Taylor’s preflight briefing.

Both of Taylor’s compasses were probably working perfectly. He was compensating for winds of 30 to 40 mph, but his TBM was facing winds up to 87 mph. Probably because of the strong headwinds, he turned onto the third leg before he crossed the checkpoint. When he failed to arrive at Fort Lauderdale at the expected time, he decided that his compasses were faulty.

Perhaps the most critical setback in the search process for the vanished flight was the mysterious failure of the Air Sea Rescue/Gulf Sea Frontier teletype system from 3:27 to 9:08. All search facilities were forced to use telephones for seeking or dispersing information, and congested lines hindered communications during that critical period. One search plane, a Consolidated PBY Catalina investigating the single-bearing fix area, might have been able to establish contact with Taylor had it not suffered complete radio failure when its antenna iced up.

Why was radar unable to find the missing planes? Commander Ray Crandell said at the time that all the radar equipment was for training use only, and is limited in its range to the immediate vicinity. It is of no value for off-shore operations.

While Taylor was facing a difficult situation somewhere over the Atlantic that afternoon, another flight that had taken off from the same base on the same mission–Navigation Problem Number One–completed the task without problems. Flight 18, led by Lieutenant Willard L. Stoll, had departed at 1:45–only 15 minutes before Taylor took off. Both flights encountered the same weather conditions and were using the same radio frequency. But Flight 18 returned to the air station without incident. It was a coincidence that investigators find interesting as well as confusing.

In addition to the coincidental circumstances brought out in the hearing, there are some serious questions that should have been considered in any investigation into the ultimate fate of Flight 19. Since Lieutenant Stoll was able to compensate for the weather changes and bring Flight 18 home safely, why did Flight 19 have more problems with the weather? One possible answer may lie in Lieutenant Taylor’s mental state. Why did Charles Taylor not want to fly the mission? And what is the significance of his cryptic remark at the briefing: I just don’t want to take this one out? What caused Taylor’s confusion?

During the entire flight the instructor’s judgment was apparently adversely affected. He was eventually overwhelmed with confusion. The available evidence suggests that his actions that afternoon were contrary to everything he knew he should have done.

According to his roommate, Taylor was very upset over a letter he had received just before the flight was scheduled to depart. Taylor apparently said nothing to anyone about the contents of the letter. He just shoved it into his pocket and took it with him on Flight 19. It seems likely that the letter may have contributed to Taylor’s anxiety and lack of concentration during the flight.

Radioman Baker at Port Everglades was unable to convince the bewildered flight leader he was over the Atlantic Ocean–not the Keys or Gulf of Mexico. Taylor’s apprehension seemed to be greater than his students’. But they could not persuade him to fly west.

What happened to the one pilot who left the formation and flew toward the air station? Baker never heard from him again, and he never reached the Florida coast.

No one can explain why Taylor or any of the other pilots failed to use their radio homing devices, which could have guided them to the air station. The base transmitter was working all afternoon, and each TBM had a receiver. Taylor refused to change to 3,000 kilocycles, saying that he needed to concentrate on keeping his planes together. That was an illogical excuse, however, because each of the TBMs could have switched to the emergency frequency, which was free of static and other interference.

Many accounts of Flight 19’s final mission have claimed that Allen Kosner, who opted out of the mission, had a premonition of disaster. Actually, Kosner denied any ominous feelings about the hop. I just decided I didn’t want to fly that day, he said when asked about his reasons, and told the scheduler in Operations to find another man. Other aircrewmen were available to fly in Kosner’s place, but none was assigned.

Why did the board of investigation’s report remain classified for more than three decades? Some have argued that the Navy wanted to conceal certain facts showing that Flight 19 had been captured or destroyed by extraterrestrials.

A more logical reason surfaced when the official report of the investigators finally became available to the public. The secrecy surrounding Flight 19 may have been the result of an attempt to conceal the inefficiency evidenced by rescue units when the flight disappeared.

During the search, Captain J.D. Morrison, an Eastern Airlines pilot, saw red flares rising into the night sky while flying 10 miles south of Melbourne, Fla. The airline pilot knew that they were coming from a small island, of which there were hundreds in that area. Captain Morrison agreed to lead a team to the site, where he witnessed the Navy’s procedure for a careful search of the area. A careful search consisted of a single helicopter that flew three passes over one island that was surrounded by marshy terrain. No ground units were involved in the effort, and the thick marshes could have easily prevented searchers from locating any of the airmen who might have crashed in that area–especially if they were unconscious or unable to signal for help. The board criticized the individuals who had been in charge of search operations–commentary that ultimately resulted in the demotion of several high-ranking officers, including one admiral.

No one really knows where or how the planes and airmen of Flight 19 finally ended their journey that fateful Wednesday afternoon. Over the years, a variety of theories have been proposed to explain their disappearance–some fanciful and some based on factual evidence.

Perhaps, as some contend, they flew into another dimension or encountered electromagnetic anomalies. Maybe the TBMs went down as a result of structural failure–or because of human error in calculating their location. Perhaps the pilots encountered vicious weather.

It is not unreasonable to believe the five TBMs simply flew until they ran out of fuel and then tried to ditch in a stormy sea on a moonless night. If so, the Avengers today are where they have been for more than 50 years–resting serenely on the sandy carpet of the Atlantic Ocean.

This article originally appeared in the July 1999 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe today!