He made it clear that although one of the saddest legacies of Vietnam was the misconception that the American soldier had somehow failed on the battlefield, nothing could be further from the truth.

The Vietnam War slipped another notch into the recesses of history with the death, on February 10, of Frederick Carlton Weyand, the last commander of Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV). He was arguably the best American general of the Vietnam War. No other general officer served in as broad a range of key roles, including divisional and corps-level command. Before assuming command of MACV, he served for almost two years as military adviser to the U.S. negotiators at the Paris Peace Talks. All his combat experience was in East Asia, including service in World War II and Korea.

Born in Arbuckle, Calif., on September 15, 1916, Weyand graduated from the University of California at Berkeley in 1939 with a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps commission. In World War II he served as assistant chief of staff for intelligence of the China-Burma-India Theater. After the war he transferred to the infantry, and in Korea he commanded a battalion in the 7th Infantry Regiment and then served as assistant chief of staff for operations G-3 of the 3rd Infantry Division.

Weyand’s European tour of duty was from 1958 through 1961, first commanding the 3rd Battle Group, 6th Infantry Division, then as chief of staff of the Communications Zone, U.S. Army Europe. Promoted to major general in November 1962, he assumed command of the 25th Infantry Division headquartered at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii in 1964. He took the division to Vietnam in 1966 and led it during Operations Cedar Falls and Junction City. In March 1967, Weyand was assigned as deputy commander of II Field Forces (IIFF) and then as commander from July 1967 to August 1968, responsible for combat operations in the southern part of South Vietnam, including the area known as the “Saigon Circle.” In the months leading up to the Tet Offensive of 1968, many of IIFF’s maneuver battalions were deployed to regions along the Cambodian border in response to increased Viet Cong attacks. But Weyand and his civilian political adviser, John Paul Vann, were uncomfortable with the operational patterns they saw developing. Communist radio traffic around Saigon was increasing while Weyand’s field units were making far too few contacts in the border regions.

On January 10, 1968, Weyand convinced General William Westmoreland to authorize the redeployment of more U.S. combat battalions around Saigon. When the Tet attacks were launched less than three weeks later, there were 27 U.S. battalions inside the Saigon Circle—instead of the 14 that would have been there otherwise. Weyand’s shrewd assessment of the situation unquestionably put the Allies in a far stronger position to defeat the attack.

Weyand left Vietnam in 1968 and was soon sent to Paris for the Peace Talks. He was back in Vietnam in April 1970 as MACV deputy commander, and then succeeded General Creighton Abrams as commander in October. Weyand oversaw the U.S. military withdrawal from Vietnam, and he stood-down MACV headquarters on March 29, 1973. Afterward, Weyand briefly commanded U.S. Army Pacific and then became vice–chief of staff of the U.S. Army under Abrams. He became the 28th chief of staff of the U.S. Army after Abrams died in September 1974.

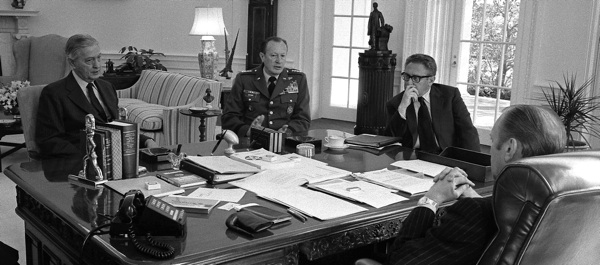

When the North Vietnamese invaded South Vietnam in force in 1975, President Gerald Ford sent Weyand to Saigon to assess the situation. Arriving on March 27, Weyand gave President Nguyen Van Thieu the blunt message that although the United States would give South Vietnam moral and financial support, its troops would not fight in Vietnam again. Back in Washington, Weyand reported that the deteriorating military situation could not be reversed without direct U.S. intervention. It was a message nobody in Washington wanted to hear.

During his final months as chief of staff in 1976, General Weyand set in motion many of the initiatives that put the Army on the road to its post-Vietnam resurrection. He also made it clear that although one of the saddest legacies of Vietnam was the misconception that the American soldier had somehow failed to measure up on the battlefield, nothing could have been further from the truth.

General Gordon R. Sullivan, 33rd chief of staff of the Army and president of the Association of the U.S. Army, described Weyand as a soldier’s soldier. “He served this nation in uniform and retired status for over 70 years. His seven decades of selfless service to this nation…sets him clearly as one of our most distinguished soldiers.”

General Frederick Weyand’s military honors and decorations included the Distinguished Service Cross, five Distinguished Service Medals, the Silver Star, two Legions of Merit, and the Combat Infantryman Badge. On February 27, he was buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific—“the Punchbowl”—the final resting place of many of the soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines with whom he served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam.

Maj. Gen. David T. Zabecki is editor emeritus of Vietnam magazine.