If you are a regular reader of Civil War Times, the Confederate battle flag is a familiar part of your world. The symbolism of the flag is simple and straightforward: It represents the Confederate side in the war that you enjoy studying. More than likely, your knowledge of the flag has expanded and become more sophisticated over the years. At some point, you learned that the Confederate battle flag was not, in fact, “the Confederate flag” and was not known as the “Stars and Bars.” That name properly belongs to the first national flag of the Confederacy.

Recommended for you

If you studied the war in the Western and Trans-Mississippi theaters, you learned that “Confederate battle flag” is a misnomer. Many Confederate units served under battle flags that looked nothing like the red flag with the star-studded blue cross. You may have grown up with more than just an idle knowledge of the flag’s association with the Confederacy and its armies, but also with a reverence for the flag because of its association with Confederate ancestors. If you didn’t, your interest in the war likely brought you into contact with people who have a strong emotional connection with the flag. And, at some point in your life, you became aware that not everyone shared your perception of the Confederate flag. If you weren’t aware of this before, the unprecedented flurry of events and of public reaction to them that occurred in June 2015 have raised obvious questions that all students of Civil War history must confront: Why do people have such different and often conflicting perceptions of what the Confederate flag means, and how did those different meanings evolve?

How was the confederate flag created?

The flag as we know it was born not as a symbol, but as a very practical banner. The commanders of the Confederate army in Virginia (then known at the Army of the Potomac) sought a distinctive emblem as an alternative to the Confederacy’s first national flag—the Stars and Bars—to serve as a battle flag. The Stars and Bars, which the Confederate Congress had adopted in March 1861 because it resembled the once-beloved Stars and Stripes, proved impractical and even dangerous on the battlefield because of that resemblance. (That problem was what compelled Confederate commanders to design and employ the vast array of other battle flags used among Confederate forces throughout the war.)Battle flags become totems for the men who serve under them, for their esprit de corps, for their sacrifices. They assume emotional significance for soldiers’ families and their descendants. Anyone today hoping to understand why so many Americans consider the flag an object of veneration must understand its status as a memorial to the Confederate soldier.

Was the confederate flag only a military symbol?

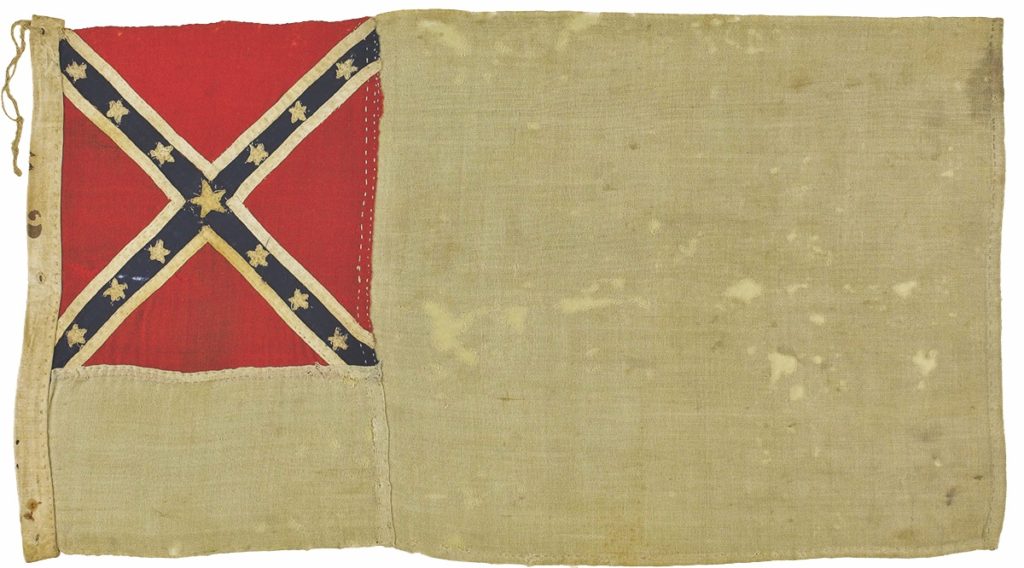

It is, however, impossible to carve out a kind of symbolic safe zone for the Confederate battle flag as the flag of the soldier because it did not remain exclusively the flag of the soldier. By the act of the Confederate government, the battle flag’s meaning is inextricably intertwined with the Confederacy itself and, thus, with the issues of slavery and states’ rights—over which readers of Civil War Times and the American public as a whole engage in spirited and endless debate. By 1862, many Southern leaders scorned the Stars and Bars for the same reason that had prompted the flag’s adoption the year before: it too closely resembled the Stars and Stripes. As the war intensified and Southerners became Confederates, they weaned themselves from symbols of the old Union and sought a new symbol that spoke to the Confederacy’s “confirmed independence.” That symbol was the Confederate battle flag. Historian Gary Gallagher has written persuasively that it was Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, not the Confederate government, that best embodied Confederate nationalism. Lee’s stunning victories in 1862–63 made his army’s battle flag the popular choice as the new national flag. On May 1, 1863, the Confederacy adopted a flag—known colloquially as the Stainless Banner—featuring the ANV battle flag emblazoned on a white field. For the remainder of the Confederacy’s life, the soldiers’ flag was also, in effect, the national flag.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

What does the confederate flag mean now?

If all Confederate flags had been furled once and for all in 1865, they would still be contentious symbols as long as people still argue about the Civil War, its causes and its conduct. But the Confederate flag did not pass once and for all into the realm of history in 1865. And for that reason, we must examine how it has been used and perceived since then if we wish to understand the reactions that it evokes today. The flag never ceased being the flag of the Confederate soldier and still today commands wide respect as a memorial to the Confederate soldier. The history of the flag since 1865 is marked by the accumulation of additional meanings based on additional uses. Within a decade of the end of the war (even before the end of Reconstruction in 1877), white Southerners began using the Confederate flag as a memorial symbol for fallen heroes. By the turn of the 20th century, during the so-called “Lost Cause” movement in which white Southerners formed organizations, erected and dedicated monuments, and propagated a Confederate history of the “War Between the States,” Confederate flags proliferated in the South’s public life.

How did the confederate flag become part of modern southern life?

Far from being suppressed, the Confederate version of history and Confederate symbols became mainstream in the postwar South. The Confederate national flags were part of that mainstream, but the battle flag was clearly preeminent. The United Confederate Veterans (UCV) issued a report in 1904 defining the square ANV pattern flag as the Confederate battle flag, effectively writing out of the historical record the wide variety of battle flags under which Confederate soldiers had served. The efforts of the UCV and the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) to promote that “correct” battle flag pattern over the “incorrect” rectangular pattern (the Army of Tennessee’s or the naval jack) were frustrated by the public’s demand for rectangular versions that could serve as the Confederate equivalent of the Stars and Stripes. What is remarkable looking back from the 21st century is that, from the 1870s and into the 1940s, Confederate heritage organizations used the flag widely in their rituals memorializing and celebrating the Confederacy and its heroes, yet managed to maintain effective ownership of the flag and its meaning. The flag was a familiar part of the South’s symbolic landscape, but how and where it was used was controlled. Hints of change were evident by the early 20th century. The battle flag had emerged not only as the most popular symbol of the Confederacy, but also of the South more generally. By the 1940s, as Southern men mingled more frequently with non-Southerners in the U.S. Armed Forces and met them on the gridiron, they expressed their identity as Southerners with Confederate battle flags.

The flag’s appearance in conjunction with Southern collegiate football was auspicious. College campuses are often incubators of cultural change, and they apparently were for the battle flag. This probably is owed to the Kappa Alpha Order, a Southern fraternity founded at Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in 1865, when R.E. Lee was its president. A Confederate memorial organization in its own right, Kappa Alpha was also a fraternity and introduced Confederate symbols into collegiate life. It was in the hands of students that the flag burst onto the political scene in 1948. Student delegates from Southern colleges and universities waved battle flags on the floor of the Southern States Rights Party convention in July 1948.

How was the confederate flag used to oppose civil rights?

The so-called “Dixiecrat” Party formed in protest to the Democratic Party convention’s adoption of a civil rights plank. The Confederate flag became a symbol of protest against civil rights and in support of Jim Crow segregation. It also became the object of a high-profile, youth-driven nationwide phenomenon that the media dubbed the “flag fad.” Many pundits suspected that underlying the fad was a lingering “Dixiecrat” sentiment. African-American news-papers decried the flag’s unprecedented popularity within the Armed Forces as a source of dangerous division at a time when America needed to be united against Communism. But most observers concluded that the flag fad was another manifestation of youth-driven material culture. Confederate heritage organizations correctly perceived the Dixiecrat movement and the flag fad as a profound threat to their ownership of the Confederate flag. The UDC in November 1948 condemned use of the flag “in certain demonstrations of college groups and some political groups” and launched a formal effort to protect the flag from “misuse.”

Several Southern states subsequently passed laws to punish “desecration” of the Confederate flag. All those efforts proved futile. In the decades after the flag fad, the Confederate flag became, as one Southern editor wrote, “confetti in careless hands.” Instead of being used almost exclusively for memorializing the Confederacy and its soldiers, the flag became fodder for beach towels, T-shirts, bikinis, diapers and baubles of every description. While the UDC continued to condemn the proliferation of such kitsch, it became so commonplace that, over time, others subtly changed their definition of “protecting” the flag to defending the right to wear and display the very items that they once defined as desecration. As the dam burst on Confederate flag material culture and heritage groups lost control of the flag, it acquired a new identity as a symbol of “rebellion” divorced from the historical context of the Confederacy. Truckers, motorcycle riders and “good ol’ boys” (most famously depicted in the popular television show “The Dukes of Hazzard”) gave the flag a new meaning that transcends the South and even the United States.

Meanwhile, as the civil rights movement gathered force, especially in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, defenders of segregation increasingly employed the use of the battle flag as a symbol of their cause. Most damaging to the flag’s reputation was its use in the hands of the Ku Klux Klan. Although founded by Confederate veterans almost immediately after the Civil War, the KKK did not use the Confederate flag widely or at all in its ritual in the 1860s and 1870s or during its rebirth and nationwide popularity from 1915 to the late 1920s. Only with a second rebirth in the late 1930s and 1940s did the battle flag take hold in the Klan.

What meaning does the confederate flag hold for black americans?

Anyone today hoping to understand why so many African Americans and others perceive the Confederate flag as a symbol of hate must recognize the impact of the flag’s historical use by white supremacists. The Civil Rights Era has profoundly affected the history of the Confederate flag in several ways. The flag’s use as a symbol of white supremacy has framed the debate over the flag ever since. Just as important, the triumph of civil rights restored African Americans to full citizenship and restored their role in the ongoing process of deciding what does and does not belong on America’s public symbolic landscape. Americans 50 or older came of age when a symbolic landscape dotted with Confederate flags, monuments and street names was the status quo. That status quo was of course the result of a prolonged period in which African Americans were effectively excluded from the process of shaping the symbolic landscape.

As African Americans gained political power, they challenged—and disrupted— that status quo. The history of the flag over the last half-century has involved a seemingly endless series of controversies at the local, state and national levels. Over time, the trend has been to reduce the flag’s profile on the symbolic landscape, especially on anyplace that could be construed as public property. As students of history, we tend to think of it as something that happens in the past and forget that history is happening now and that we are actors on the historical stage.

Because the Confederate battle flag did not fade into history in 1865, it was kept alive to take on new uses and new meanings and to continue to be part of an ever-changing history. As much as students of Civil War history may wish that we could freeze the battle flag in its Civil War context, we know that we must study the flag’s entire history if we wish to understand the history that is happening around us today. Studying the flag’s full history also allows us to engage in a more constructive dialogue about its proper place in the present and in the future.

Contextual Perspectives

John Coski recently said during a presentation about the Confederate battle flag, “this symbol has an accretion of meanings across time and across different people.” My own ancestry is a combination of people of African and European descent. My mother and her parents attended segregated schools in Southside Virginia. My great-great-great-grandmother and her children were free blacks before the war, but they lived in constant fear of slave patrollers—and were unable to obtain a legal education or vote.

My great-great-great-grand-father, however, was a white slaveholder and the father of my third great-grandmother’s children. Through that branch of my family I am also connected with many Confederate soldiers and two members of Virginia’s 1861 Secession Convention.

It is true that many Confederate troops did not own black people. But the Confederate leaders did not stutter when it came to their support of slavery and white supremacy.

my GREAT-GREAT-GREAT-GRAND-FATHER, HOWEVER, WAS A WHITE SLAVEHOLDER AND THE FATHER OF MY THIRD GREAT-GRANDMOTHER’S cHILDREN.

Emmanuel Dabney, National Park Service Curator

The battle flag represents a gamble by 11 states (and another two states with representation in the Confederate Congress) to create a separate slaveholding republic. It symbolizes the struggles of men on well-known battlefields like Manassas, Shiloh, Chickamauga and Gettysburg. But there is no denying the role the battle flag played during the war’s bitter aftermath and Reconstruction and its use by 20th-century white supremacist groups. That same banner, in addition to images of Robert E. Lee and the American flag, was hoisted high during the 1948 “Dixiecrats” convention in Birmingham, Ala., held because of opposition to Harry Truman’s advocacy of a civil rights plank in the Democratic Party platform.

Then there’s the viewpoint of all those people who marched for access to the ballot. Some of those same individuals were spit on for trying to order a sandwich at a lunch counter, or were called the “N word” because they sought access to a truly equal education. They view the flag, and variations thereof, with understandable contempt.

Why we can’t ignore the confederate flag debate

Recommended for you

We cannot ignore America’s long history of prejudice. Because the Confederate battle flag is seen as a symbol of that prejudice, the call to remove it from public display is warranted in government spaces such as the grounds of the South Carolina Capitol. Original flags should be preserved and exhibited in museums.

Yet removing the flag from public display in South Carolina or Mississippi does not resolve issues such as equal access to the ballot box. It does not change the fact that this nation still jails disproportionate numbers of minorities, or mitigate the unfairness of the justice system for those people, or improve the way they are treated after they have served their time.

I am interested in resolving actual problems, so we can move beyond arguing about a piece of fabric. We need to acknowledge America’s long history of biases. But we also need to make sure we do not further contribute to divisiveness.

Is it ever OK to display the confederate flag?

The Confederate battle flag does not belong anywhere near a public statehouse. It should be displayed within its historical context, such as at museums, reenactments, living histories, etc. It is also, I believe, appropriate to own one if you are an avid historian and lover of the time period, but take care to remember and be sensitive about what it can symbolize to others.

That being said, after a lengthy discussion in our home, I had to furl the small Confederate flag that was displayed with other Civil War memorabilia. I now feel as though I’ve hidden away my lineage in a dresser drawer. It’s a battle I can’t win.

I’m sorry, all you Prillaman boys in the 57th Virginia Infantry, who laid it all on the line so many times, captured at the Angle at Gettysburg with your proud colors and returned to service because you had conviction. I believe you were wrong in your cause. But I believe you fought for that cause with your every fiber, because at heart you were Americans. Rest in peace. You will not be forgotten, and I won’t allow anyone to tarnish you or shove shame down my throat. I will lay this flag at your graves, alongside an American flag. You were both. You can claim both.

I now feel as though I’ve hidden away my lineage in a dresser drawer.

Lars Prillaman, organic farmer, fiddler, and living historian

As William Faulkner famously wrote in “Intruder in the Dust”:

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Long-street to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet…

There is an internalized and inherited sense of loss in us Southerners. Shelby Foote spoke of this in several inter-views. Some things, perhaps, we shouldn’t have held onto, but I think even those of us who wish to be sensitive to others’ feelings on those symbols just get tired of the sense of losing. Even in our own living rooms.

My ancestors in the 57th Virginia Infantry served under the battle flag. Prillamans were captured, killed and wounded following that banner. I hate the cause that they stood for, but I am fiercely proud that they stood.