During the Vietnam War, Skyraider Dieter Dengler—who had learned survival skills as a youth in Germany and who was a Navy legend for his extraordinary escape and evasion skills—began planning an escape from Laotian prison immediately.

*****

On February 1, 1966, German-born U.S. Navy pilot Lieutenant (j.g.) Dieter Dengler’s A-1 Skyraider was shot down over Laos during a secret bombing mission. A day later, while attempting to signal rescuers flying above heavy jungle territory controlled by the Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese Army regulars, Dengler was captured. After he was marched over several days from village to village—managing to escape once before being recaptured—he was finally imprisoned in a jungle-shrouded POW camp guarded by Pathet Lao on February 14. Six other prisoners were already there: Air Force 1st Lt. Duane Martin, a rescue helicopter pilot shot down in September 1965; another American, Eugene “Gene” DeBruin, an Air America crewman who had bailed out of a burning cargo plane in September 1963; and four other Air America crewmen from the flight, Thai civilians Prasit Promsuwan, Prasit Thanee and Phisit Intharathat, and To Yick Chiu, a Hong Kong native the men called Y.C.

Dengler, who had learned survival skills as a youth in wartime and postwar Germany and who was a Navy legend for his extraordinary escape and evasion skills, immediately began planning an escape. Some four months later, after being relocated to another camp and following meticulous preparation, Dengler and the others were ready, targeting July 4 for their mass escape. In mid-June, however, after the prisoners overheard the guards planning to kill all of them and return to their villages because a drought had caused a severe shortage of food and water, the POWs decided they could not wait any longer to make their breakout.

The following is from Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam War, copyright 2010 by Bruce Henderson, published by Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publisher.

The day before the POWs planned to escape, and be “alive and free—or dead,” Dieter received a beating from the Pathet Lao. His offense: He had used two sticks to drag over to the door of the hut a small corncob that had been thrown to a young pig the guards were fattening. The kernels had already been devoured, leaving only the shriveled cob—filthy with the pig’s manure. But Dieter was starving, and he intended to eat it. Before he could begin, the guard they called Moron ran over, yelling and pointing his rifle. He entered the hut, slapped the foot-blocks on Dieter, and dragged him outside. A group of guards had gathered in the yard. As if prosecuting a court case, Moron waved the corncob as evidence, then flipped it to the pig. For Dieter, the symbolism was clear: Prisoners are less than pigs. Then Moron began beating him with his rifle butt. Other guards joined in. When they threw him back into the hut, where all the prisoners had been herded during the beating, a bloodied Dieter stared stony-faced into the yard, saying nothing to the others. Prasit broke the silence, telling Dieter not to forget when he killed the guards to kick them in the heads “so they’ll rot in hell.”

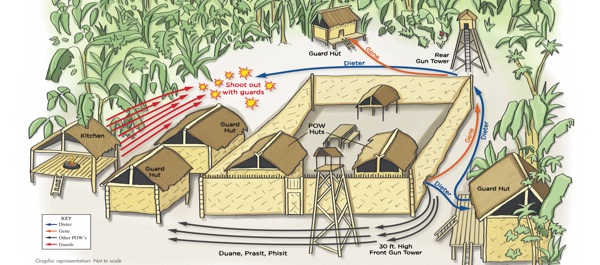

For weeks they had been updating their scale model of the camp, marking where all the guards and guns were located from morning until evening. Taking turns peering out between the cracks of their huts, the prisoners had observed every detail, no matter how small, and came to know their captors’ routines as well as their own. They had even been able to determine about how long it would take for reinforcements to reach the camp from the nearest village. One morning the guards spotted strange footprints, and one of them took off to get help; he was back with armed reinforcements in six hours. They had considered and rejected a nighttime escape, primarily because it was impossible to venture far in the jungle in the dark and they knew the guards would be on their trail come daylight. The best opportunity for escape remained the period of time that the guards put down their weapons to go to the kitchen around 4 p.m. to pick up their evening meal. The prisoners repeatedly timed the interval; the trip to and from the kitchen generally took 2½ minutes. In that time, the prisoners would have to slip from their huts, get outside the stockade, secure the guns, and be ready to overtake the guards in camp.

Everyone in the escape plan had assigned tasks. Dieter was to be the first out of the walled compound, then enter the nearest guard hut, where three or four rifles were usually left inside. He was to gather the guns and arm Phisit and Prasit as they emerged from under the fence. The three of them were the most capable with weapons. Neither Duane nor Gene was eager to participate in a shootout, and Y.C. couldn’t handle a rifle. Gene had a backup role with a weapon, however. He was to head for a guard hut on the back side of the compound to retrieve a Thompson submachine gun. As Dieter swung around behind the stockade and proceeded toward the kitchen, Gene was to remain on the porch of the hut with the submachine gun and provide supporting fire only if needed. At the kitchen, the Thais were to order in Laotian for the unarmed guards to surrender. With Dieter guarding the back door, they hoped to round up the guards without firing the guns, since the sounds of a shootout would reverberate throughout the valley for miles, alerting all villagers and Pathet Lao alike to trouble at the camp. While Dieter, Thanee and Phisit secured the guards, Gene and Prasit would set up a hand-grenade booby trap on the trail leading up from the village, then hide nearby and ambush anyone heading for the camp. Meanwhile, Duane and Y.C. would search the huts. They would place the guards in foot-blocks and handcuffs and lock them in the prison huts until they decided what to do with them. Then, they could hold the camp and signal aircraft nightly until being spotted and rescued. If shots were fired in the taking of the camp, however, everyone knew that all bets were off, as enemy reinforcements could be expected within hours.

In Dieter’s mind, there was no contingency for failure. If they tried to escape and failed, he expected either to be killed in the attempt—his preference—or executed soon thereafter. There had never been a viable alternative for him. Even before the prisoners heard about the guards’ plan to kill them, he had not intended to slowly waste away in a jungle prison camp and die from disease or starvation or beatings.

Weeks earlier, the prisoners had loosened a large support pole in the American hut by pouring water and urine at its base and working it back and forth until they could lift it out. After loosening some logs close to the floorboards, they now had a way to quickly exit the hut. Then, they put everything back and “covered up all traces” of their advance preparation. Dieter had also dug a hole underneath the fence next to the hut, and then covered it up with leaves and bamboo. He had accomplished all this when the prisoners were still being let out for long periods in the morning and when the guards in the gun towers were napping or otherwise inattentive, as they often were.

Some hours after the beating over the corncob, the prisoners were let out into the compound. They sat at their wooden picnic table in the center of the yard, slurping down watery rice broth, which had become their only daily meal. The camp dog—as skinny as them and probably not long for the world given the guards’ own extreme hunger—lingered under the table looking for scraps. There were none, of course, but the prisoners were always willing for the dog to lick any sores on their feet and legs, as they had found its saliva aided the healing process. Gesturing to the guards that he had to take a leak, Dieter slipped behind the hut to see if the logs were still loose. They moved easily. Also, the hole under the fence looked as if it had not been discovered. Having lazy guards who did not bother to walk the fence line was an advantage.

In the event they could not stay at the camp to make contact with planes overhead, the prisoners agreed they would split into two groups before fleeing overland. There had been earlier talk of staying together as one group but Dieter was opposed to the idea. If they had to hump through the jungle to freedom, he wanted to be with Duane and Gene because the three Americans got along and trusted one another.

The three Thai were a natural team, and given how well Phisit, the former paratrooper, knew the jungle, Dieter figured they had an excellent chance of making it. In fact, Phisit offered tips to the Americans about finding food in the jungle, such as edible ferns that grow along the waterways and figs that could be eaten green or ripe. The Thais told about the hospitality of their people, especially the monks, and suggested that if the Americans made it across the border into Thailand they should seek refuge at a temple until they could make contact with U.S. forces. The Thais and Americans were in agreement that westward was the way to proceed, with impenetrable jungle, at least two mountain ranges, and North Vietnam to the east.

The oldest prisoner, Y.C., the Chinese radio operator, was the odd man out. Set to travel with the Thai group, Y.C. suddenly fell ill with what was believed to be an attack of elephantiasis. Caused by parasitic worms transmitted by mosquitoes, the tropical disease left his legs weak and swollen, and his scrotum badly distended. In severe pain, he could barely walk. The Thais balked at taking Y.C. with them.

The Americans talked it over. If they were able to hold the camp and make air contact and set up a rescue operation from here, Y.C.’s condition would not be an issue. But if they had to head for Thailand and evade enemy trackers en route, there was no way he could keep up. It was a terrible thought to condemn a fellow prisoner to certain death, and they struggled with the dilemma. Yet everyone knew that they would be at a distinct disadvantage carrying a sick man who had trouble walking.

Finally, Gene said he and Y.C. would go together. They would make it over the first ridge to the south, then “lie in wait for air contact.”

“Don’t be a fool,” Dieter said. “We want you with us.”

“And I want Y.C.,” Gene said, adding that if Dieter and Duane were rescued, “be sure someone looks for us and tell them where to look.”

Dieter appreciated Gene for being “our peacemaker.” Whenever there was an impasse among the prisoners, more often than not it was “kind and good” Gene who stepped in to resolve things. Now, even though he understood it lessened his own chance for rescue, Gene would not leave behind his Air America crewman, who had become a good friend during their interment. When they divvied up the sacks of dried rice, Dieter and Duane made sure Gene and Y.C. each received “twice the amount” of everyone else, knowing they might have to hold out longer for rescue.

On escape day, the hours dragged toward the guards’ evening meal.

Already there had been one aborted effort. The day before, after Dieter had crawled out the back of the hut and was ready to slip under the fence, Phisit had called it off from the other hut because two of the guards were unaccounted for in the kitchen. Dieter had to put everything back into place, and get back inside. When he asked Phisit later what had happened, the Thai said he didn’t think it was the right time. Recalling how opposed to the escape Phisit had long been, Dieter thought he might now be playing mind games. A “boiling mad” Dieter told Phisit if he did that again once the escape was underway that he would come back after getting a weapon and shoot him. Dieter could see that Phisit understood there was “nothing idle” about his threat.

As the hour approached 4 p.m. on June 29, 1966, Phisit again turned “worried and cautious,” sending word that maybe the escape should be put off again. “Not on your life,” Dieter answered back.

In the Asian prisoners’ hut, which was closest to the kitchen, Thanee was counting the guards as they arrived for food. He passed the information to Y.C., squatted in the doorway. In English, Y.C. called out in a hushed voice to Duane, stationed in the doorway of the American hut, and Duane passed the word to Dieter and Gene.

“Guards entering kitchen.”

“Guards don’t have weapons.”

They waited for the final count.

“All in the kitchen, but one’s missing,” Duane said urgently.

They speculated he might have gone to check the animal traps in the woods.

“Hell, let’s go,” Dieter said.

Duane and Gene agreed.

“It’s on,” Duane called out in a stage whisper to the other hut.

Dieter pulled out the loosened pole and logs, and climbed out the opening. Burrowing under the fence like a crazed groundhog, Dieter squeezed through and headed for the nearest guard hut. He leapt onto the porch, and crept across the bamboo flooring that creaked with his every step. Inside, he found two Chinese-made rifles and a U.S. M-1 carbine with a full 15-round magazine. While with the Air Force shooting team he had spent many hours on the range firing M-1s; he would keep this lightweight, semi-automatic weapon for himself. On the way out, he picked up a full ammunition belt with extra magazines.

As he came off the porch, other prisoners were emerging from under the fence. Gene was already making his way down the fence line toward the rear of the compound. Phisit and Prasit came toward Dieter, who gave them the loaded Chinese rifles and some ammo. The two Thais headed off in the direction of the kitchen with Duane following.

Dieter caught up with Gene. As they rounded the corner under the now-empty gun tower, Gene peeled off for the hut where the guard on tower duty routinely left the Thompson submachine gun before going for food. As soon as Dieter rounded the far corner of the stockade, he could see the guards milling about inside the open-walled kitchen hut.

The next instant, the guards “realized something was going on” and began yelling at each other and scrambling from the kitchen. They did not run toward the front of the stockade—the direction from which the Thais should have been coming—but toward Dieter.

“Yute! Yute!” yelled Dieter. He pressed the butt of the M-1 tightly between his chest muscle and the front ball of his shoulder, tilting his head so that his closest eye looked straight down the top of the barrel. His index finger rested lightly on the trigger.

At that moment a shot rang out. Dieter felt the speeding bullet whiz past his head. He spotted a guard in the kitchen with a rifle pointed his way. So much for the theory that the guards had no weapons! Dieter squeezed the trigger and dropped the guard with one shot.

Amid excited screams, the horde of guards closed on Dieter, who felt “all alone…out in the open.” He wondered what happened to the Thais armed with the Chinese rifles and Gene with the submachine gun.

Running for Dieter at full speed with a machete held menacingly over his head was Moron. From a few feet away, Dieter fired point-blank at the bare chest of the guard who had beaten him for taking the pig’s corncob. The force of the blast lifted Moron off the ground, threw him back several feet and spun him around. His limp body fell to the ground “dead right on the spot” with a sizable exit hole in the center of his back.

Dieter swung around to see another guard with a machete trying to outflank him. Although the M-1 fired only once each time the trigger was pulled, by rapidly squeezing and releasing the trigger he got off a fast-rate of fire. The guard collapsed on the ground, holding his side and shrieking. With no hesitation, Dieter fired again to “finish him off.”

The remaining guards were trying frantically to reach the jungle.

“Where the hell—is everybody?” Dieter yelled.

Then, like a backwoods Kentuckian on a squirrel hunt, he steadied himself and opened fire. He hit one more guard through the neck as he ran away. Needing to reload, Dieter slammed home a new magazine. He shot another guard just as he entered the jungle. The guard dropped from sight, then sprang up holding one arm. Dieter kept “banging away” at the guard as he vanished ghost-like into the thick vegetation.

Duane came running up carrying a carbine he had found in a guard hut. “The clip—the clip,” he stammered, explaining it had fallen out every time he tried to release the safety to fire the weapon.

Dieter showed him he was pressing the clip release, not the safety.

At least one guard had gotten away. There was also still the missing seventh guard, who could be nearby. In spite of all the dead guards sprawled on the ground who would never again abuse POWs, the outcome was disastrous given that the plan had been to capture the guards without firing a shot or letting anyone get away to return with reinforcements. The prisoners’ bold plan to hold the camp and make air contact was no longer viable. They had no choice now. They would have to gather whatever supplies they could find and head into the jungle.

When Dieter went to retrieve his and Duane’s boots from where they had been hanging under a hut with the other shoes, they were gone. He knew exactly who had taken them: the Thais, who had gotten there first, and also “picked clean” all the mosquito nets and anything else they thought they could use without offering to share with the others. Carrying stuffed rucksacks, they had been the first to depart the camp.

Dieter and Gene had an emotional farewell. Gene had found the submachine gun in the guard hut, although when he stepped outside the shooting was over. He now had the weapon slung over one shoulder. As they shook hands, Dieter looked into Gene’s face and wanted to say something about how he should come with him and Duane instead of remaining behind near the camp. But he knew Gene had his mind made up, and would not leave his sick friend behind. Unable to find the words he wanted to say to his fellow American, Dieter shook Gene’s hand warmly.

“Go on, go on,” Gene implored. “See you in the States.”

Dieter and Duane took off toward the west and Thailand, although in an hour they had “no more reference” to direction due to the dense foliage, and could not see more than five feet in any direction. In their weakened states and unaccustomed to exercise, they started “vomiting right away.” They were soon held up by a solid wall of bramble brush. The camp dog had followed them, barking, and they were afraid he would end up giving them away. The dog had his own escape plans, however, and before disappearing into the woods he found a dug-out corridor under the thicket; Dieter and Duane crawled through after him. A short time later they reached a ridge. Exhausted, they fell to the ground. When they had recovered, Duane wanted to offer a prayer. They came up on their knees, with eyes closed and hands folded before them.

“God, please help us now. Please let us live.”

POSTSCRIPT TO EXCERPT During the next three weeks, Dieter and Duane struggled to find their way out of the oppressive jungle, miraculously evading capture numerous times and somehow finding enough nourishment to fend off starvation. As Duane was brutally killed by a machete-wielding villager, Dieter managed yet another amazing escape. A few days later, after 22 days in the jungle, barely eluding guerrilla search parties and as a hungry black bear closed in, an emaciated Dieter heard the sound of U.S. Air Force Lt. Col. Eugene Deatrick’s Spad flying overhead. In a “million-to-one shot,” Deatrick spotted Dieter waving and—within 24 hours of dying, according to doctors—was soon lifted from the jungle. Two months later, Dieter was well enough to hold a televised press conference and testify before a Congressional committee.

Awarded the Navy Cross, Dieter left the Navy in February 1968. Vowing to never be hungry again, he bought and operated a German-style restaurant on Mount Tamalpais near San Francisco. In a house he built next to it, he hid a large supply of food staples under the kitchen floorboards. After selling his restaurant, Dieter become an airline pilot and, in the late 1970s, made a return to Laos on a POW fact-finding mission. Diagnosed with Lou Gehrig’s disease (ALS) in 2000, Dieter died on February 7, 2001. He was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

About the Author: Bruce Henderson served with Dengler aboard USS Ranger in 1966. Read about Bruce Henderson and His Quest to Write Full Story of Dieter Dengler’s Life.