Among Henry Tyndall “Dick” Merrill’s achievements, the most surprising may be that he survived to become an aviation legend. So many equally daring young pilots died barnstorming or trying to fly the airmail or passengers across a country whose aircraft and airways system weren’t ready for them.

A born gambler with a passion for dice, cards and horse racing, Merrill survived despite odds that often seemed stacked against him. He learned to fly in a war-surplus Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” and then, with only minimal wind-in-the-wires experience, began barnstorming around the South and Midwest. He moved up to take a job as an early airmail pilot, bailing out of one biplane at night after searching futilely for an airfield that wasn’t socked in by fog.

After Merrill became a captain at Eastern Air Lines, his boss, “Captain Eddie” Rickenbacker, labeled him the luckiest pilot in his “Great Silver Fleet” when he saved the passengers and crew of a twin-engine airliner with an exhausted fuel tank by crash-landing in tree tops that cushioned its descent. He also wound up in a Canadian bog at the end of the first of his two trailblazing transatlantic flights in the mid-1930s. During World War II, he flew the “Hump” over the Himalayas to supply China’s Allied defenders. Back in civilian life, traveling in the jump seat of a Lockheed Constellation bound overwater for Miami in 1948, he helped save the 48 “souls” on board after a runaway propeller tore through the plane’s midsection, killing a purser (Dick helped the regular crew nurse the crippled aircraft back to a military airfield in Bunnell, Fla.).

Over a flying career that spanned the history of modern aviation, Merrill logged more documented hours in the air than any other airline pilot. His well-publicized exploits would make him a giant even at a time when an awed public considered all airline pilots larger than life. He charmed and soothed fearful passengers ranging from presidents and royalty to Damon Runyon–type mobsters, and established speed records in aircraft ranging from the twin-prop Douglas DC-2 to the Lockheed L-1011 widebody jetliner. Frequently in the news, he enjoyed the celebrity of a latter-day rock star, hobnobbing with the rich and famous and marrying a glamorous actress half his age.

After serving a stint as Eastern’s chief check pilot, Merrill reluctantly retired as a captain in command on October 3, 1961, yielding to new federal age restrictions. Yet in the mid-1960s, when my job as aviation writer for the Miami Herald allowed me to get to know Dick, he had a lot of flying left in him. Despite his mandated retirement from carrying revenue passengers, he continued as Eastern’s “captain emeritus,” piloting VIP trips and making friends for the airline as he had for over 30 years.

Born on February 1, 1894, Merrill grew up in Mississippi, where his ability to pitch a baseball with either arm earned him the unlikely nickname “Dick,” after ambidextrous storybook sports hero Dick Merriwell. He was talented enough to play minor league ball, once winning both games of a doubleheader by pitching right-handed in one, left-handed in the other. But his attention was drawn skyward after watching aviatrix Katherine Stinson stunting in 1914. Upon the outbreak of World War I, he joined the Navy with dreams of dogfighting German Fokkers. But his lessons with French instructors left him frustrated, complaining, “I didn’t learn a thing.” His interest in aviation never waned, even after he joined the railroad, as his father had done. When the federal government announced the sale of surplus Curtiss Jennys in 1920, he and a buddy scratched up $600 for a plane and began taking flying lessons.

Despite limited experience, Merrill soon ventured into barnstorming. His youthful good looks, blue eyes and natural charm helped spare him from starvation in that unforgiving line of work. As crowds demanded ever-more-dangerous stunts, Dick’s charm enabled him to win a relatively safe job offering plane rides for the famed Gates Flying Circus.

After five years of barnstorming, he learned that the government was hiring pilots for a pioneering network of airmail routes. His skill and commitment to safety—including being a teetotaler amid legions of heavy drinkers—made him an attractive candidate. However, his first job flying nights between Atlanta and New Orleans in a weatherworn biplane provided no guarantee of longevity.

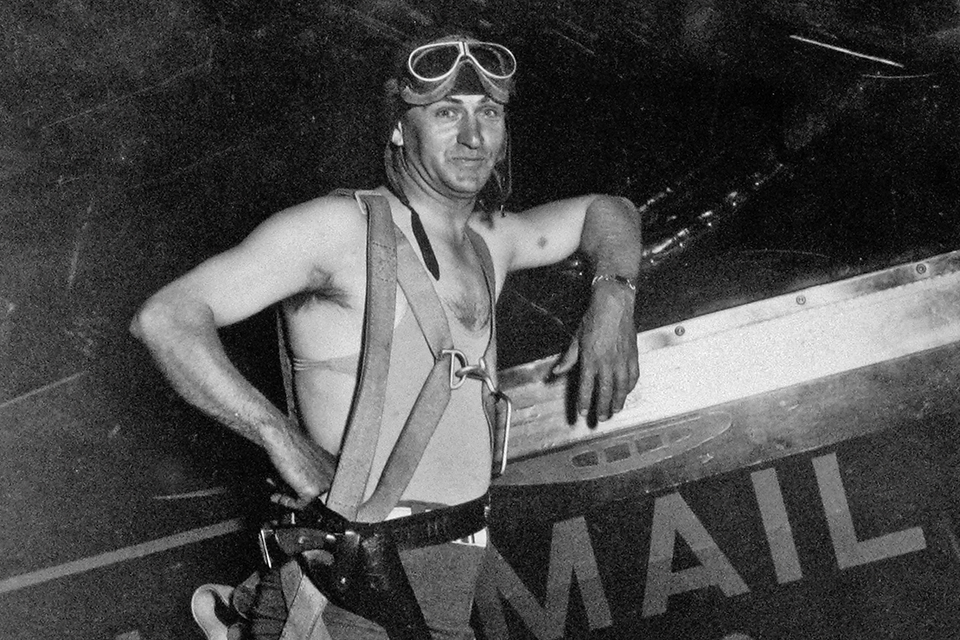

In May 1928, he upgraded to a company founded by wealthy young Harold Pitcairn, flying the mail in a more modern aircraft between Atlanta and Richmond. The ambitious Pitcairn had hired an engineer to design the Pitcairn Mailwing specifically to serve a government postal route. Still, flying at night over mountains was a treacherous undertaking. One night, with an almost empty fuel tank, he had to roll the aircraft inverted to bail out in his bulky winter flight suit. Lying injured in a field far below, he heard men searching the woods, wondering aloud where they could find the pilot’s body. “Here’s the body,” he called out.

Not only did Merrill survive his years flying the mail, he even made money doing it. By 1930, when newly formed airlines were beginning to take over the airmail business, he boasted a two-year period when he never canceled a Pitcairn Aviation flight and earned an unprecedented $13,000 a year.

During those airmail years he learned to supplement his income through gambling, a risky enterprise he would pursue obsessively for years. His early winnings helped the young bachelor drive a flashy 1928 Packard roadster through Pitcairn’s home base of Richmond. He frequently traveled with a lion cub named Princess Doreen in an era when pilots embellished their derring-do reputation with exotic pets and fancy cars.

Harold Pitcairn sold his company to North American Aviation only months before the 1929 stock market crash, and Merrill found himself flying for NAA’s Eastern Air Transport division. As the Depression deepened, the holding company was forced to sell out to General Motors in 1933. WWI ace Eddie Rickenbacker, who had urged GM officials to acquire Eastern, was named the airline’s president and general manager in December 1934; he would assume control of the airline four years later.

Meeting Merrill for the first time, Rickenbacker recognized that he had acquired more than a pilot. Dick clearly was a public relations asset, whose quiet confidence helped retain customers for Eastern despite Rickenbacker’s own growing reputation of indifference to passenger service. Captain Eddie rewarded Merrill by letting him command Eastern’s 1934 inaugural flight of its new DC-2 between New York and Miami, which he flew in record time. Because Dick hit it off with newspapermen in strategic cities, Rickenbacker asked him to inaugurate each new aircraft in following years, uncharacteristically yielding the spotlight in return for the publicity bonanza his record flights generated. (When the airline received its first Lockheed Super Constellation on May 17, 1947, for instance, Merrill delivered it from Burbank to Miami in a record six hours, 54 minutes and 57 seconds.)

Rickenbacker demonstrated his support in 1936 when he granted the young captain time off to undertake a dream flight across the Atlantic. Merrill had persuaded two different backers to finance the first Atlantic solo trip before Charles Lindbergh became an international idol in May 1927. However, one would-be backer, a New Orleans riverboat gambler, was forced to pull out after losing everything in a night of shooting dice; the other, Edward R. Bradley, who bred Kentucky Derby–winning race horses, withdrew his offer after newspapers accused him of sending Merrill on a suicide mission. Dick, who had lined up a long-range Bellanca to make the flight, would insist years later that “I could have beat Lindbergh if the newspapers hadn’t scared the colonel and caused him to back out.”

Determined to try for a new record, Merrill found a financial angel and copilot in showman Harry Richman, who had struck it rich with his “Puttin’ on the Ritz” musical reviews. Richman agreed to provide and help fly his newly purchased single-engine Vultee V-1A after listening to Merrill’s pitch at a Miami Beach club where Richman was performing. “Harry, let’s take that airplane and fly her to Europe,” Merrill urged. “Then we’ll gas her up and fly her right back. It’s never been done.” Richman, never one to shy away from the spotlight, quickly agreed, although he had only recently earned his pilot’s license.

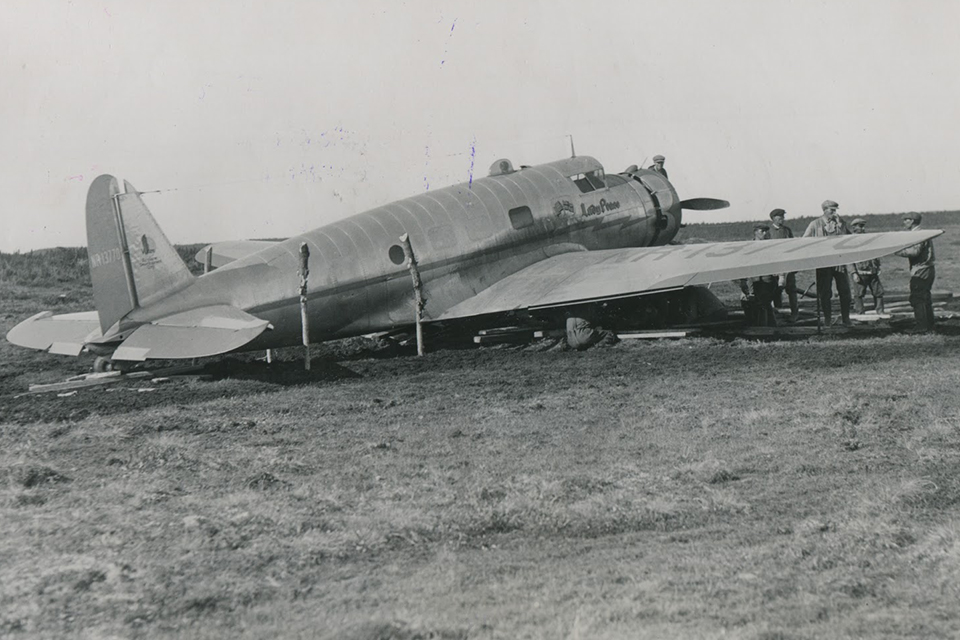

Richman’s Vultee, with Merrill in the left seat, wallowed into the air from Long Island’s Floyd Bennett Field on September 2, 1936, bound for London. Gorged with extra fuel, the airplane they named Lady Peace barely made it aloft despite a borrowed 1,000-hp Wright Cyclone engine. Aviation’s odd couple had begun the first transatlantic roundtrip by airplane.

Merrill and Richman had filled the plane’s cavities with thousands of ping-pong balls to help it remain afloat if they had to ditch at sea. They were soon grateful for that precaution, as storms forced them to fly just above the waves. When they finally touched down in Wales, they found they had made the crossing in 18 hours and 36 minutes, the fastest time to date. They flew into London’s Croydon Airport the next day to receive a hero’s welcome.

The “victory lap” back to New York was jeopardized when the inexperienced Richman, panicking during a storm, jettisoned 500 gallons of fuel and forced the pair to land in a Newfoundland bog. Rickenbacker had to mount an Eastern Air Lines rescue mission to get the Vultee airborne for the flight home to New York.

Merrill made aviation history again the following year with the first commercial transatlantic flight. This time he selected a professional to share the cockpit, 27-year-old EAL copilot Jack Lambie. Together they would help publisher William Randolph Hearst scoop his newspaper rivals by flying photos of King George VI’s May 10, 1937, coronation back to the States. Dick acquired and modified a twin-engine Lockheed 10E Electra for the flight with money from a questionable sponsor, Wall Street wheeler-dealer Ben “Sell-’em-Short” Smith. Merrill would come to regret the trust he had placed in Smith.

Preparing for departure from Floyd Bennett Field on May 9, Merrill was being interviewed by reporters when he was interrupted by news that Germany’s airship Hindenburg had gone down in flames while attempting to land at Lakehurst, N.J., killing 35 passengers and crew members. Merrill was instructed to delay the takeoff so he could to carry film of the disaster to London, where Hearst owned a newspaper. Dick agreed, in part because the revised assignment would give him the first commercial flight in each direction.

As soon as the film arrived, the aircraft dubbed the Daily Express took off and soon flew into an all-too-familiar North Atlantic storm. The well-teamed EAL pros negotiated the storm and droned on across the miles. They were aided by the Lockheed’s new autopilot—equipment the tightfisted Rickenbacker refused to install on his airliners. EAL pilots liked to joke—discreetly, of course—that their boss saw no need for equipment not standard on a WWI Spad.

Because the Electra’s radio equipment was still rudimentary, the pilots couldn’t contact the Croydon Airport tower as they crossed the English seacoast. They landed at an RAF field to obtain directions, then took off again for the 20-minute flight to London and another spirited welcome. A messenger pushed through the crowd to pick up the Hindenburg photos, then raced away toward Hearst’s newspaper offices. Two days later, Merrill and Lambie took off on the return flight with the promised coronation photos for Hearst’s New York editors. Completing that flight would win the pilots congratulations from President Franklin D. Roosevelt and a Harmon Trophy for Merrill.

If the daring roundtrip added to Merrill’s fame, it did little for his fortune. His trust in Ben Smith proved to be naive. Smith had persuaded the pilots to make a post-flight tour and movie, promising to reward Merrill by giving him the Electra. Instead, Smith sold the aircraft to the Russian government and disappeared. Merrill and Lambie received only $2,500 each for starring in a quickie film called Atlantic Flight (Dick promptly lost his share at Santa Anita racetrack).

Overshadowed by Merrill’s transatlantic flights was his 1935 odyssey from Kansas City to Chile’s southern tip in a single-engine Northrop Gamma to help locate explorer Lincoln Ellsworth and his expedition party. The explorers were stranded after crashing on a polar sea icepack. Ellsworth’s wife pleaded with Dick to fly the Gamma down across the Andes to an airport where rescuers could use it to search for the missing party. He agreed to make the treacherous flight with the Gamma, provided by TWA. Returning to his regular schedule with Eastern, he was pleased to learn later that the party had been rescued—his only reward for the adventure. “I flew 10,700 miles alone through some of the most miserable weather in the world and went through four seasons in four days,” Dick summed up. “I got expenses down and back—not a two-dollar bill extra.”

Merrill interrupted his flying exploits in 1938 to wed showgirl and actress Martha Virginia “Toby” Wing in a surprising match announced first by broadcaster Walter Winchell, one of Dick’s many celebrity pals. Toby, at 22, was two decades younger than the captain. On meeting the new Mrs. Merrill at a party, comedian Bob Hope said he was pleased to see her, adding, “and I’m glad to see you brought your father along.” According to Toby, her husband was not amused.

To the skeptics’ surprise, the couple would spend their life together, enjoying socializing at nightclubs and racetracks at both ends of Eastern’s New York–Miami route. But it wasn’t all fun and games. Despite Merrill’s skill with cards and dice, he could lose as big as he could win, and his gambling remained a problem for years. In Rickenbacker’s autobiography, he claimed credit for suggesting to Toby that buying an expensive home with a big mortgage would restrict her husband’s gambling. Whether following his advice or Toby’s own sharp eye for real estate, the couple bought a showplace Spanish-style home on Miami Beach’s De Lido Island. “Dick had to forgo the ponies to pay for the house,” Rickenbacker wrote.

Their storybook lives were disrupted by the death of their infant son, Henry, who died in his crib in 1940. (Their second son, Richard Wing Merrill, known as Ricky, would be murdered at his Miami home in 1982.) In their grief over Henry’s death, they were comforted by their Catholic faith and a growing circle of friends. Those friends would come to include Dwight D. Eisenhower, for whom Dick commanded a campaign charter leading up to Ike’s November 1952 election as president. That campaign covered 40,000 miles. Dick took special pride in being able to ease Mamie Eisenhower’s fear of flying, as he had calmed so many others (including Toby, whose father had been crippled in a plane crash). After Eisenhower won, the Merrills attended the inaugural dinner.

New federal regulations caught up with Merrill on October 3, 1961, when he made his last LGA-MIA flight as the Federal Aviation Agency’s new age-60 limit on airline captains went into effect. Although he was already 67, it was a bitter pill for a man who still met all the FAA’s physical requirements. “It finally took the FAA to put me out of business,” he complained. EAL wasn’t about to let its star pilot vanish into retirement, however. It created a consulting title that would allow him to continue flying, at reduced pay, so long as there were no revenue passengers on board. He would remain as the airline’s captain emeritus, piloting publicity flights and even handling the dangerous task of ferrying aircraft with failed engines to a maintenance base.

His “retirement” took a novel turn in 1966, when he was invited to help pilot an unprecedented round-the-world sortie in a new Rockwell Standard executive jet. The 72-year-old aviator immediately replied, “When can we get started?” Merrill asked entertainer Arthur Godfrey, a friend he had checked out previously in a Lockheed Constellation, to join a four-man crew. Merrill and Godfrey would share flying duties with Fred Austin, a TWA captain, and Karl Keller, an engineering test pilot for Rockwell Standard.

The Jet Commander departed from New York LaGuardia on June 4, 1966, returning 90 hours and 23,524 miles later after touching down in a dozen countries. Their trip included an unscheduled stop in Karachi when suspicious Pakistani fighter pilots forced them to land and explain what they were doing. The crew set 21 international speed records en route.

After the 1970 death of Sidney Shannon, a onetime airmail pilot who had risen to senior vice president of EAL, Merrill agreed to serve as curator of an aviation museum that Shannon’s son founded in Fredericksburg, Va., to honor his father. Merrill donated his own memorabilia to the museum as part of a collection that includes a JN-4 Jenny, a Pitcairn Mailwing and a sister ship of the transatlantic Vultee V-1A. That collection is now housed at the Virginia Aviation Museum in Richmond.

In 1972 Merrill helped EAL deliver its first L-1011 TriStar from California to Miami. Boosted by a hurricane-like tailwind, the aircraft averaged a record 710 mph groundspeed. Although he would take the controls of the supersonic Anglo-French Concorde six years later with an EAL evaluation team, the TriStar flight was his last record-breaker. Merrill would close his logbook with about 45,000 hours in the air, nearly five years. He had accumulated almost 8,000 of those hours after officially retiring from EAL in 1961. Because of more restrictive modern limitations on airline flying time, an FAA representative told Dick that his record was unlikely to be broken.

That record and his other achievements earned him a gold medal from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale in 1970, validating his life’s work. He cherished the award, which had been won in 1927 by the aviator he wanted to beat across the Atlantic, Charles Lindbergh. Merrill already possessed a Harmon Trophy, awarded to him a decade after Lindbergh won the honor.

Dick and Toby would spend their final years at their home in Lake Elsinore, Calif. But as Dick told his biographer, “My runway is running out.” He died at the age of 88, with Toby at his bedside, on October 31, 1982. Toby would follow him in March 2001, working until the end to preserve her husband’s legacy in aviation history.

Don Bedwell has contributed to numerous publications through the years. He edited and published American Airlines’ employee and retiree newspaper, Flagship News, until he retired to Ohio in 1998, and authored Silverbird: The American Airlines Story. Further reading: Jack King’s biography, Wings of Man: The Legend of Dick Merrill; and Rickenbacker: An Autobiography, by Edward V. Rickenbacker.