When last we left the Eastern Front, the Wehrmacht teetered on the brink of disaster. Well planned Soviet attacks had first encircled an entire German field army (the 6th, under the unfortunate General Friedrich Paulus) at Stalingrad, then systematically dismantled the Allied armies serving alongside the Germans: first the Romanians (hit in the initial offensive north and south of Stalingrad, code-named Operation Uranus); then the Italians defending up the Don (Operation Little Saturn); followed by the Hungarians upriver (the “Ostrogozshk-Rossosh operation”); Operation Gallop, targeting German forces on the Donets river and into the Donets basin (the Donbas) itself; and finally, Operation Star on the extreme Soviet right, tearing great gaps in the defensive front of the German 2nd Army.

When last we left the Eastern Front, the Wehrmacht teetered on the brink of disaster. Well planned Soviet attacks had first encircled an entire German field army (the 6th, under the unfortunate General Friedrich Paulus) at Stalingrad, then systematically dismantled the Allied armies serving alongside the Germans: first the Romanians (hit in the initial offensive north and south of Stalingrad, code-named Operation Uranus); then the Italians defending up the Don (Operation Little Saturn); followed by the Hungarians upriver (the “Ostrogozshk-Rossosh operation”); Operation Gallop, targeting German forces on the Donets river and into the Donets basin (the Donbas) itself; and finally, Operation Star on the extreme Soviet right, tearing great gaps in the defensive front of the German 2nd Army.

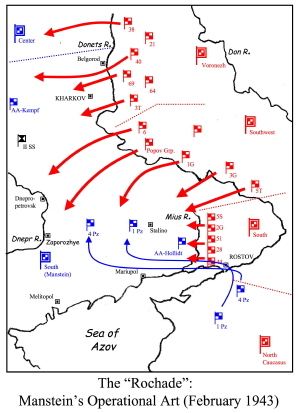

All across the southern portion of the massive front, Soviet offensives were churning forward, reaching out ever farther to the west and south, seeking the German flank over the middle Donets river, and indeed, threatening the crucial crossing points over the mighty Dnepr river itself at Kremenchug, Dnepropetrovsk, and Zaporozhye. For the first time, the Soviets were going deep on the Wehrmacht, and the stakes were high. If the Soviet crossed the Dnepr, they would succeed in smashing Army Group South itself—an operational victory that might well have strategic consequences. Confidence was high in all levels of the Soviet command, and that confidence extended all the way up to Moscow.

As the Book of Proverbs tells us, however, “pride goeth before a fall.” At the very moment that the Soviets were riding high, driving all before them and motoring into the clear, the wheels were already beginning to come off of their offensive. Each mile that their tank divisions “went deep” was another mile away from their own supply bases. Their mighty T-34s were wearing down, treads and transmissions above all; the lines of communication were no longer delivering replacements in a timely fashion; and even soldiers who were accustomed to pushing beyond their limits, as the men of the Red Army certainly were, were beginning to succumb to fatigue.

Of course, none of this would have mattered in the absence of an enemy. Unfortunately, the Soviet drive to the Dnepr had to contend with a German army that, no matter how battered and bruised, still retained some formidable operational skills: veteran tank crews who hung together even when losses had reduced their battalions to battle groups (Kampfgruppen); infantry who fought with the courage of desperate men a long way from home who still hoped to get there; and, above all, ruthless commanders trained to maneuver boldly on the operational level—i.e., in large formations like divisions, corps, and armies—in order to win battles even when they happened to be outnumbered.

Exhibit A in that last category was the new commander of Army Group South, Field Marshal Erich von Manstein. Despite the godawful situation maps laid out in front of him, he could still perceive some old truths. He had an enemy lunging forward at top speed, while his own formations were falling back on their supply bases over the Dnepr. At some point, the iron laws of war told him that the Soviets would begin to wane while his own strength would be waxing. All he had to do was predict the precise moment.

His biggest worry were the German formations still lying far to the east in the Caucasus region, the legacy of an exceedingly ill-fated campaign in late 1942. They needed to be recalled, and soon, but Manstein knew that he had to tread carefully there. Asking Adolf Hitler to issue retreat orders rarely ended well for anyone, he well knew. The situation was so dire this time, however, that even the Führer had to agree, and soon, 1st Panzer Army (General Eberhard von Mackensen) was scurrying back to the west as far as a bad road and network would permit.

What Manstein had in mind was nothing less than a Rochade, what a chess player would call a “castling” move. Mackensen’s 1st Panzer Army and the 4th Panzer Army of General Hermann Hoth had, up until now, formed the extreme right wing of the German battle array. They now received orders to hurry clear over to the other side of the theater to form the German left. If they arrived in time, Manstein would deploy them facing north, a position from which they would have a clear shot at all those immense Soviet formations fighting deep battle and driving helter skelter towards the Don river crossings to the west.

It wasn’t a sure thing. The German formations to the south were advancing over ground that was soggy from the early thaw, while the Soviet armies to the north were still motoring over good, hard frozen ground. Nothing about war is ever a sure thing, however, and this was about the only shot that Manstein had. If 1st and 4th Panzer Armies arrived in time, his plan just might work.

A big if.

More next week.

For the latest in military history from World War II‘s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.