The conclusion of four years of grueling civil war called for a celebration, according to The New York Times. “This war has been singularly wanting in pomp and pride and circumstance,” the paper opined on May 4, 1865, expressing its hope that “before Sherman’s and Meade’s armies are broken up, arrangements will be made for a great military display when the public could express its obligations to these great and famous armies in some striking and worthy manner to both their soldiers and their leaders.” Three weeks later, courtesy of the War Department, the Times got its wish.

The Grand Review had to be the most enormous spectacle the nation had ever seen. As a pageantry of power, it had to display the soldiers and their generals who had won the war. It would have to be held in the nation’s capital. It also had to be a catharsis for the nation, alleviating four years of anxiety and grief.

The 150,000 triumphant soldiers assigned to participate in the Grand Review included 90,000 from the Army of the Potomac, which had fought Robert E. Lee’s army for more than a year in Virginia and forced his surrender at Appomattox. Another 60,000 were in 178 regiments from William T. Sherman’s Army of the West, made up of the Army of Georgia and Army of the Tennessee. Both had battled Joseph E. Johnston’s and other Confederate armies for more than a year, capturing Atlanta and Savannah, Ga., and forcing Johnston’s surrender near Durham, N.C.

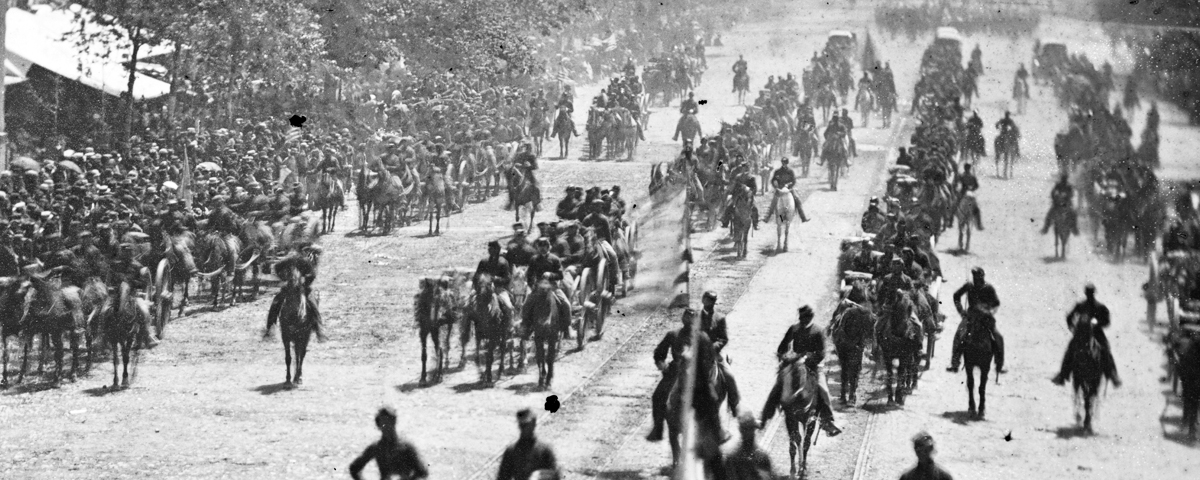

These bronzed veterans, the most superb material ever molded into military might, marched in a glorious two-day military pageant through the nation’s capital. At least 250,000 men, women and children cheered themselves hoarse while shedding tears of admiration and joy, showering the men with thousands of flowers, singing, laughing and waving for more than six hours each day. The men marched better than ever. Every soldier became an instant celebrity; the whole country claimed them as its heroes.

For a week before the parade, hotels and boarding houses were jammed to their rafters while many spectators slept outdoors or stayed up all night. Private homeowners rented bed space in parlors and attics, rooftops, window space and porches at “fabulous prices” for the legions of visitors.

They, plus the city’s residents, added considerably to the monumental logistical problems created by the 150,000 soldiers and 25,000 horses participating in the two-day review. Providing food, accommodations, water, forage and sanitary facilities—including the disposal of manure—strained the capacity of all concerned.

Upon Sherman’s arrival in his camp on the Washington Road three miles north of Alexandria, Va., Commander in Chief Ulysses S. Grant directed him to prepare his troops for the review. “I will be all ready by Wednesday [May 24] though on the rough,” he replied. “Troops have not been paid…and clothing may be bad but a better sort of arms and legs cannot be displayed on the continent!”

In Sherman’s Army of the West, the XV and XVII Corps were in Maj. Gen. O.O Howard’s Army of the Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum’s Army of Georgia included the XIV Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis, and the XX Corps, headed by Maj. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams. All four corps had been with Sherman’s army since it left Chattanooga, Tenn., in May 1864.

In the afternoon of May 19, the Army of Georgia marched to Arlington Heights, Va., footsore and exhausted. The men set up tents near Fort Runyon not far from Arlington House, Lee’s former home, which had been used as Union Army headquarters and its grounds as a cemetery for Union soldiers. They joined a thousand other camps on both sides of the Potomac River. Regimental bands played daily and smoking campfires twinkled nightly. They could see the unfinished Washington Monument, the White House, the Capitol and the Smithsonian Institution. They had marched 1,400 miles in the year since they left Chattanooga at the start of Sherman’s march on Atlanta.

Slocum’s army remained in Arlington Heights until May 24, preparing for its review before President Andrew Johnson, his Cabinet, Generals Grant and Sherman, selected congressmen and other dignitaries.

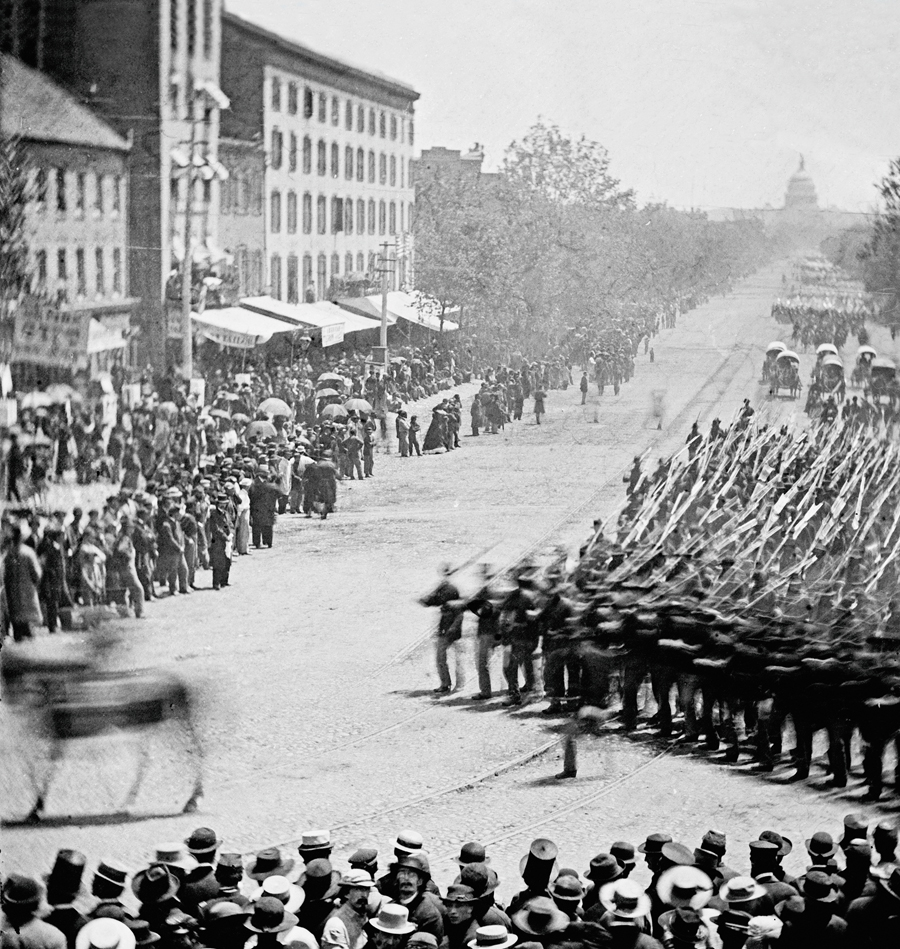

Grog shops closed for three days to minimize possible brawling, upsetting a number of thirsty men; but some speakeasies were in business on the city’s outskirts. Police were busy arresting pickpockets, thieves, prostitutes and counterfeiters. By daybreak on the first day, crowds lined Pennsylvania Avenue. Buildings along the parade route were bedecked with American flags; red, white and blue bunting; and floral displays and black crepe ribbons to reflect mourning for President Abraham Lincoln. For the first time since his assassination, flags were raised to full staff, signifying the end of the official mourning period. Welcome signs and banners hung from buildings and across street intersections. “THE ONLY NATIONAL DEBT WE CAN NEVER PAY IS THE DEBT WE OWE TO THE VICTORIOUS UNION SOLDIERS” read a banner on the Treasury Building. Over its entrance hung the torn battle flag of the Treasury Guard Regiment. Arches of flowers and evergreen boughs bridged Pennsylvania Avenue. Another banner over the avenue read, “ALL HAIL OUR WESTERN HEROES.”

Cavalry patrols were posted along the parade route to keep crowds clear of the tree-lined, cobblestone avenue. At intersections they kept vehicles and spectators out of the line of march. Mathew Brady set up large glass-plate cameras on tripods on temporary scaffolding above 15th Street. Hawkers sold purple lemonade.

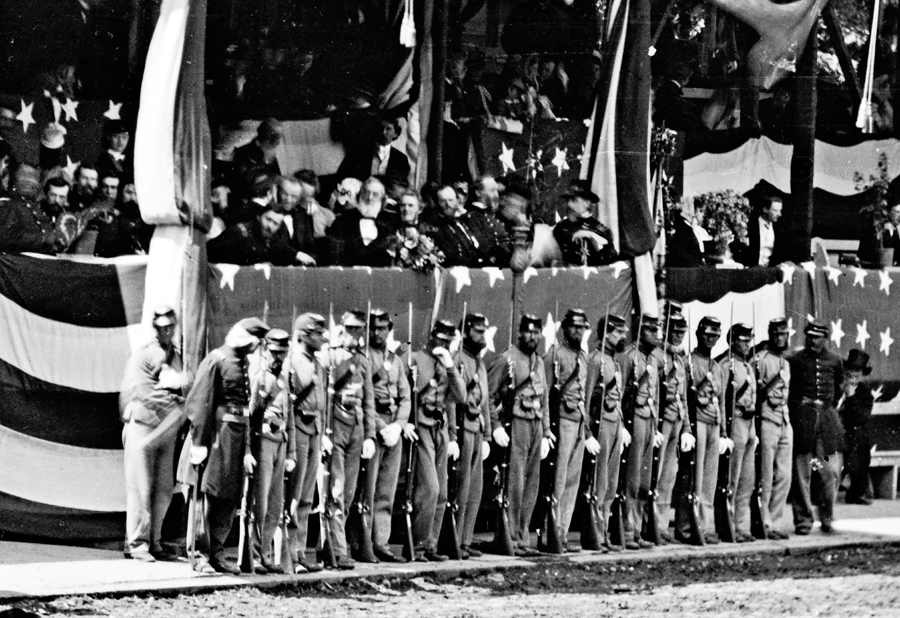

The reviewing stand was at the end of 1½-mile parade route on Pennsylvania Avenue. On the White House lawn facing the avenue were long rows of elevated, terraced seats reserved for special guests. In the center of these seats was a separate, elevated section for the covered presidential reviewing stand. It was handsomely decorated with national colors, flags and banners bearing names of the armies’ famous battles.

Another section was reserved for governors and their citizen guests. Two other reviewing stands were erected by private citizens, including a Boston financier; one for wounded and sick soldiers and the other for deaf children. Behind these terraced seats was the White House. A separate stand was erected across the avenue in Lafayette Square for use by congressmen, public officials, lesser notables and the press.

The military trial of John Wilkes Booth’s alleged co-conspirators in the assassination of President Lincoln—which had already attracted a number of onlookers to the city—was adjourned during the review. From May 20 through May 23, visitors arrived to greet their sons and husbands, sightsee and witness the parade. Beginning May 21, boats from Alexandria unloaded passengers throughout the day, and roads from Maryland and Virginia delivered buggies filled with travelers, including parents with children. Washington was already overcrowded with visitors when another 100,000 appeared on scheduled and special excursion trains from across the country. The first overcrowded train arrived from New York at 10 a.m. May 23—an hour after the Army of the Potomac’s review had already begun.

The first part of the two-day parade began promptly at 9 a.m., with the single boom of a cannon. From around the Capitol a solitary horseman swung into view. It was bespectacled Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade, riding Blackie, his favorite horse. As the crowd roared “Gettysburg, Gettysburg!” Meade and his staff headed the Army of the Potomac’s parade until it reached the presidential reviewing stand. Next to the president sat Grant, his young son Jesse on his lap. His wife Julia was there, too. The other seat by the president was reserved for Meade on May 23 and Sherman on May 24. Also present were Meade’s wife Margaretta and his two sons, Spencer and Willie; Sherman’s wife Ellen and his son Tom; and various Cabinet members, diplomats and other high-ranking generals.

There, he saluted President Johnson, Grant, Sherman and the other dignitaries, while they stood in acknowledgment. He dismounted, entered the stand, shook hands with the president and others, and took his seat next to Sherman, while his entire army continued to march past.

While watching the “spit and polish” men of the Army of the Potomac march by, Sherman said to Meade, “I’m afraid my poor tatterdemalion corps will make a poor appearance tomorrow, when contrasted with yours.” Meade, pleased with his army’s performance, replied, “people will make allowances.” Sherman actually wanted the crowd to see his army as the Confederates had seen it—including bummers, freedmen and pioneers—when it marched the next day.

Maj. Gen. George Custer, true to form, provided added excitement for the thousands of spectators just as he approached the reviewing stand astride his horse, Don Juan. According to the Times, “Custer rode a powerful horse, restive, and at times ungovernable. When near the Treasury Department, the animal madly dashed forward to the head of the line. The General vainly attempted to check his course, and at the same time endeavoring to retain the weight of flowers which had previously been placed upon him. In the flight, the General lost his hat. He finally conquered his horse, and rejoined his column. Passing the President’s stand he made a low bow, and was applauded by the multitude.”

Nobody in Sherman’s army slept the night before its parade began. The last two days had been spent furiously preparing for their review. They knew that the uniforms of the “Easterners” from Meade’s army would far outshine theirs. The pants, shirts and jackets of the “Potomacs” were newer, and they wore shiny shoes and buttons, paper collars and white gloves. In contrast, the Westerners were mostly a ragtag mob of unkempt ruffians. Some had floppy caps of wool or straw that looked like empty flour sacks, while others wore black slouch hats like Sherman’s. Still others were bareheaded and barefooted. “I think it is a shame that the government does not pay off Sherman’s army so that the officers can appear [decent] for the Review,” an embarrassed Capt. George I. Robinson of the 123rd New York Infantry wrote his wife on the day they arrived in Arlington.

A few had obtained parts of new uniforms after their arrival at Goldsboro, N.C., but some refused to wear them. If their old clothes were good enough to wear to Washington, they were good enough for the parade. “Their uniforms looked dingy [as if] the smoke of numberless battlefields had dyed their garments, and the soil of insurrectionary states had adhered to them,” remembered the 123rd’s Sgt. Rice C. Bull. They had brushed, mended and washed their mudsplattered, tattered, and for some, bullet-pierced, uniforms in the Potomac, polished their buttons, blackened what was left of their shoes, burnished their leather straps, and cleaned and polished their cartridge boxes, rifles, and bayonets until they glistened.

“Our guns, which were our pride and joy, could not have looked better,” Bull observed.

Brig. Gen. John D. Geary, commander of the XX Corps’ 2nd Division purchased, with his own money, white gloves for his men.

Many in Sherman’s army were convinced they had done more to end the rebellion than the Army of the Potomac while it was trying to capture Richmond. They had taken Chattanooga, Vicksburg, Atlanta, New Orleans and Savannah, and made it possible for the Mississippi to flow “unvexed to the sea,” as Lincoln put it. They had also freed hundreds of thousands of slaves in Mississippi, Tennessee, Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia and the Carolinas.

At midnight, the soldiers ate breakfast of hardtack and coffee, still on short rations. They were called into marching order at 2 a.m. The 123rd New York led its brigade, which in turn led the XX Corps and Slocum’s Army of Georgia. Each man marched with his blanket roll over his right shoulder and two days’ cooked rations in his haversack at his left hip.

By 6 a.m., they halted at the Long Bridge spanning the Potomac, about three miles from their Arlington camp. The weather was pleasant; the trees in Lafayette Square were leafing out. As sergeants issued orders, they marched by company across Long Bridge and along Maryland Avenue on the eastern side of the C&O Canal, gaping at the just-completed Capitol dome in the distance. They assembled in rutted side streets around the Capitol grounds, the dust settled by recent rain.

In the fall of 1862, when the untested army had crossed Long Bridge in the opposite direction, the 123rd New York had numbered 1,000. Now, four years later, a scant 400 remained as it passed in review. Before the parade began, they had a last sip of ice water from barrels placed by citizens on Maryland Avenue, adjacent to the Capitol.

Government clerks sat on the Treasury Building roof. Boys perched in trees and on lampposts waved handkerchiefs and flags. By the parade’s start, the crowd lined the street 8 to 12 feet deep, waving miniature flags and shouting, “Sherman, Sherman!” Those with curb tickets were allowed to pass through the line of guards holding back the rest of the crowd. The troops marched under blue skies with light, white clouds, moderate temperatures and a cool breeze.

One reporter wrote that a large number of those who came to witness the Army of the Potomac’s review on the first day stayed over to witness Sherman’s “rough-necked cowboys” on May 24, helping to make the second day’s audience even bigger. Jam-packed as they were, the visitors remained “gay and jovial, ignoring all vexations. Good feelings were aided by the recent, cooling rains and breezes.”

Spectators had seen the “Potomacs” for four years, but Sherman’s “greasers” were novelties as well as celebrities. Sherman’s men were getting their first glimpse of the capital while its citizens got their first glimpse of them.

At 9 A.M., while church clocks chimed, an artillery piece was fired. Sherman’s 60,000 men, accompanied by 14 artillery batteries, uncoiled from around the Capitol like a gigantic 15-mile-long python. At the front of each company were its tallest men, with veterans as left and right guides for each company. Sherman led the parade, accompanied by Howard, an ardent abolitionist who recently had been named head of Lincoln’s newly formed Freedmen’s Bureau. With his empty right sleeve pinned to his jacket, Howard guided his horse with his left hand.

Looking straight ahead and taut with pride, “Uncle Billy” rode slowly and calmly like a Roman emperor on Lexington, his favorite horse, both of them bedecked with flowers. He adjusted the stiff-brimmed hat, part of his unfamiliar new uniform. A New York World reporter claimed the cheering was “greater than the day before…the whole assemblage waved and shouted, as if each was his personal friend….Sherman was the idol of the day.”

As Sherman passed Lafayette Square on his dark bay, followed by his staff and escort, he recognized and saluted Secretary of State William H. Seward standing at the window of Blair House. Seward, still feeble from the severe wound he received the night of Lincoln’s assassination, returned the gesture.

At the reviewing stand, Sherman saluted with his sword as the band played the popular new song “Marching Through Georgia” in his honor. Everyone in the presidential stand acknowledged his salute by taking off their hats, rising to their feet and cheering. He then dismounted and entered the stand with Howard.

Sherman greeted his wife and son, and shook hands with the president and Grant. Next in line was Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton with his round, whiskered and expressionless face. Sherman, still smarting over Stanton’s interference in his surrender negotiations with Joe Johnston, stiffened as Stanton extended his hand and looked coldly past him long enough to make evident his insult—then moved past to shake hands with the other Cabinet members. Convinced Stanton had wanted to ruin his reputation, Sherman nursed his resentment for years. But on this day, he remained in the stand to review his troops.

The stage-struck country boys of Sherman’s army marched 20 abreast, as straight as tightened twine from curbstone to curbstone. Those who had watched the “White Collar galoots” march the day before knew they were “no great shakes at marching.” Each brigade marched to its own band, some looking like “moving flower gardens,” covered with bouquets the crowd had tossed to them. The troops marched in perfect cadence as each guided left to keep exact alignment. Only a single footfall was heard as boots and bare feet struck the cobblestone pavement in unison.

“The marching was hard on our feet,” one soldier wrote, but “the march had to be in stile [sic].” The interval between companies was maintained with precision as they passed the reviewing stand with long elastic strides, their polished guns at right shoulder shift. There was power and confidence in that long stride, as if they were lords of the world. “We couldn’t look at the reviewing stand,” one private remembered. “If Lincoln had been there, I’m afraid our line would have broken up.”

The spectators and reporters who stayed over on the second day consistently noted that Sherman’s “Wolves” were taller, they looked older and stronger, and their marching stride was several inches longer. Their beards and hair were untrimmed. But even Meade’s officers conceded that Sherman’s men marched better, and their faces were more intelligent, self-reliant and determined. Overall, Sherman’s “slouch hats” overtopped the Easterners in their physical appearance and soldierly bearing.

Spectators also wondered why the soldiers did not seem excited, but marched with an easy, satisfied nonchalance—though with some exceptions. When a shout of “Hurrah for Ohio” came from a group of Buckeyes, or a regimental colonel would call three cheers for the president or Grant, their facial expressions showed instant animation and enthusiasm as dirty caps were tossed by brawny arms and wild whoops as loud as Niagara Falls rent the air. Yet not one in 50 of Sherman’s men would cast his eyes at the adoring audience.

It was noon before the Army of Georgia began its march around the Capitol onto Pennsylvania Avenue, with a tremendous roar of welcome from the crowd. Slocum’s staff followed in a single line that stretched across the avenue. Behind the staff, Slocum’s escort was led by Lt. Walter F. Martin of the 123rd New York. He had been captured on the skirmish line during Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, escaping twice with the assistance of slaves. After returning to the regiment in Atlanta, Martin refused an offer of leave so he could participate in Sherman’s March to the Sea.

The XX Corps led off, looking even better, some of its men believed, than any other corps. “An army like that could whip the world,” observed the Prussian ambassador. Former Ohio Sen. Tom Corwin concluded, “They marched like lords of the world.”

Brig. Gen. H.A. Barnum of Syracuse, commander of the 3rd Brigade, 2nd Division, XX Corps, was roundly cheered. In his first battle, he was left on the field, dying. But he recovered to fight four more battles before he was wounded again. When he arrived in Washington for the review, he brought 35 enemy flags that his men had captured.

Apprehension finally overcame Sherman as the column of troops turned right to pass the Treasury Building. He glanced once over his shoulder to see how well his men were aligned, noting how the “glittering muskets [with fixed bayonets] looked like a solid mass of polished steel swinging with the regularity of a pendulum.” His eyes were wet. The sight, he said, was the most satisfying moment of his life. They were his war-torn warriors, at their best fighting weight and strength.

The crowds had cheered and wept for the more than six hours it took Sherman’s army to complete the review. Not a soul departed. None seemed weary of gazing at the troops. Sherman stood for the entire review. Spectators who had been glued to the spectacle lingered after it was over. Sherman, with his wife and son, did not leave until 4:30 p.m., after the last of the pack mules and their riders were out of sight. Then the street and fire departments took on the task of cleaning up the aromatic manure from thousands of horses.

Sherman bid his troops farewell. “As in war, you have been good soldiers, so in peace, you will be good citizens,” he said.

Within a week, the armies were disbanded.

D. Reid Ross is the author of Lincoln’s Veteran Volunteers Win the War (2008, SUNY Press), which includes soldiers’ reflections on the review—and their commitment to Lincoln, ending slavery, and saving the Union.

This article was originally published in the May 2015 issue of America’s Civil War.