U.S. Navy submarine officer John P. Cromwell went to extraordinary lengths to protect a vital American secret from the enemy

[dropcap]“T[/dropcap]he day was a pretty one, with whitecaps coming over the decks.”

After seven hours of fire and fury and fear, that was Fireman 1st Class Joseph N. Baker’s clear memory of the November 1943 afternoon when an aggressive, infinitely persistent Japanese destroyer attacked the submarine USS Sculpin. All morning the two vessels had played a deadly game of cat and mouse some 250 miles northeast of Truk Atoll. The enemy had dropped more than 50 depth charges, finally forcing the submarine to the surface. Sailors dashed to the deck guns, Joe Baker among them. They were able to get off a few inconsequential three-inch rounds before the destroyer opened fire. The first volleys killed the sub’s skipper and two-dozen officers and men topside. Then came the order to abandon ship.

Baker jumped overboard, joining 41 others—half the crew—as they swam away from Sculpin and toward the destroyer, watching their ship slowly slip beneath the waves. “The last I saw of her was the radar mast going under,” said Torpedoman Harry F. Toney. “She made a beautiful dive.” Some of the men were still aboard—dead, trapped, or so badly injured they could not escape. But one man, 42-year-old Captain John Philip Cromwell, a senior submarine officer, chose to go down with Sculpin. As he told the only officer to survive: “I know too much.”

Cromwell’s decision was perhaps rooted in his upbringing in the patriotic town of Henry, Illinois. Its 2,000-some residents lived along the banks of the Illinois River surrounded by farms raising cattle and corn. His father, Dr. Edward Cromwell, was a prosperous and prominent physician active in local politics. John—nicknamed “Bud”—and his siblings grew up in a loving, church-going family.

For a boy, life in Henry could be idyllic—larking in the river in summer, skating on Mud Lake in winter. The family always looked forward to the town’s annual Fourth of July celebration. It started off with a roaring cannon salute, followed by a grand parade, athletic contests, a reading of the Declaration of Independence and a patriotic oration, and wrapped up in the evening with fireworks. Bud often participated in these displays of national pride, strutting with his classmates down Edward Street. When he entered high school, World War I was raging in Europe, which may have piqued his interest in a military career. He graduated in 1919 in a class of 22. After a year of military college prep, and with a congressional appointment to the United States Naval Academy in hand, he caught a train east to Annapolis in June 1920.

Midshipman Cromwell discovered he was fascinated by engineering, which became his passion. After graduating in 1924 the navy posted him to one of their newest battleships, the USS Maryland. When he was detached from the dreadnought two years later he volunteered for something altogether different: the submarine service. He qualified at the sub school in New London, Connecticut, in 1927, then joined the crew of USS S-24. Over the next 16 years, as he climbed rapidly through the ranks, Cromwell hopscotched between tours at sea and on land. Perhaps his favorites were a three-year postgraduate course studying the intricacies of diesel engineering and, in 1936, command of his first—and as it turned out, only—ship: USS S-20. One of his crew, Motor Machinist’s Mate Harvey D. Stultz, thought the world of him. “To me he stood at the very top as an officer and a gentleman. A dedicated, stern, just, man who helped you to the limit when you were in the right, and gave stern punishment when you erred.”

In May 1941 Lieutenant Commander Cromwell joined the staff in Pearl Harbor of the Pacific Fleet’s submarine commander, Rear Admiral Charles A. Lockwood, as engineer officer. His family—wife Margaret, son Jack, and daughter Ann—planned to follow in July. On his way out to Hawaii he made a last visit to Henry. Despite his peripatetic life Bud returned as often as he could to his hometown—a place, his son recalled in 2012, “my father loved dearly.” When his family joined him in Honolulu, they settled in for what they thought would be a pleasant tour of duty. Jack Cromwell said that his father’s new job would allow him to be home every night; “we would have led a very normal life.”

That normalcy was shattered just six months later, on Sunday, December 7, 1941. As the bombs rained down, Bud Cromwell was lying in a ward at the naval hospital being treated for hypertension, but he leapt from the bed to go to his duty station at Pearl Harbor. He spent the first half of 1942 helping put the sub force on a war footing. In midsummer Cromwell was assigned to command the six-boat Submarine Division 203.

By mid-1943 new submarines were steaming into Pearl in ever-increasing numbers. One way to take advantage of this growing capability, Admiral Lockwood thought, would be to develop a coordinated attack doctrine loosely based on German navy “wolf pack” tactics, in which multiple submarines concentrated on a single target. That summer the submarine force began running three-boat simulated attacks on incoming U.S. convoys, with Cromwell participating as a critical observer in the first two exercises.

Another of Cromwell’s regular responsibilities was standing watch at the Joint Intelligence Center Pacific Ocean Area. The center functioned as a clearing house for all incoming Imperial Japanese Navy radio traffic. U.S. Navy analysts decrypted, translated, and passed these intercepts, code-named “Ultra,” to relevant commands for action. The transmissions were often extremely detailed and included ship names, cargos, and routes with specific coordinates for daily noon positions that allowed the analysts to follow the formation of enemy convoys. Lockwood used this information to pinpoint-place his submarines for the greatest destructive effect on Jap-anese commerce. So precious and sensitive a resource was Ultra that the number of men privy to its secrets was strictly limited. John Cromwell was one of the few.

Ultra intelligence played a key role in the November 20, 1943, invasion of the Gilbert Islands, dubbed Operation Galvanic, the first step in the United States’ bold island-hopping strategy to wrestle control of the Central Pacific. The American submarine fleet’s contribution was to position nine submarines along the routes Ultra indicated the Japanese would use to reinforce their troops on Tarawa. Among the nine was USS Sculpin.

The Sculpin was one of 10 Sargo-class submarines built in the late 1930s. Each was 310 feet long, with a top speed of 21 knots and a range of 11,000 miles. One of the class, USS Squalus, made national headlines in May 1939 when it sank off the coast of New Hampshire during a test dive, with the loss of 26 sailors. Sculpin was first on the scene and stood by throughout rescue operations that hauled 33 survivors to the surface. The navy raised Squalus in the summer of 1939, rebuilt it, and recommissioned it in May 1940 with a new name—USS Sailfish. Nearly four years later, fate would have a tragic twist in store for Sailfish and Sculpin.

Sculpin was already a veteran of eight war patrols when it was assigned to Operation Galvanic. For the ninth run Commander Fred Connaway, 32, took over the helm. His only war patrol had been two months earlier as a “prospective commanding officer” on USS Sunfish, patrolling off Taiwan. In fact, a third of Sculpin’s 84 crew members were new to it; many of them, having recently joined the growing submarine force, had never seen combat. Others aboard had seen plenty. Diving officer Lieutenant George E. Brown Jr. had made five runs with USS S-40, and four on Sculpin. Nine others had been with the boat since the war began.

Admiral Lockwood decided to send now-Captain John Cromwell on the mission to form, if called for, a wolf pack to interdict enemy ships bound for the Gilberts. Before the sub departed Pearl, Lockwood cautioned Cromwell not to share any information about Ultra with anyone, “in case the submarine was sunk and prisoners taken.”

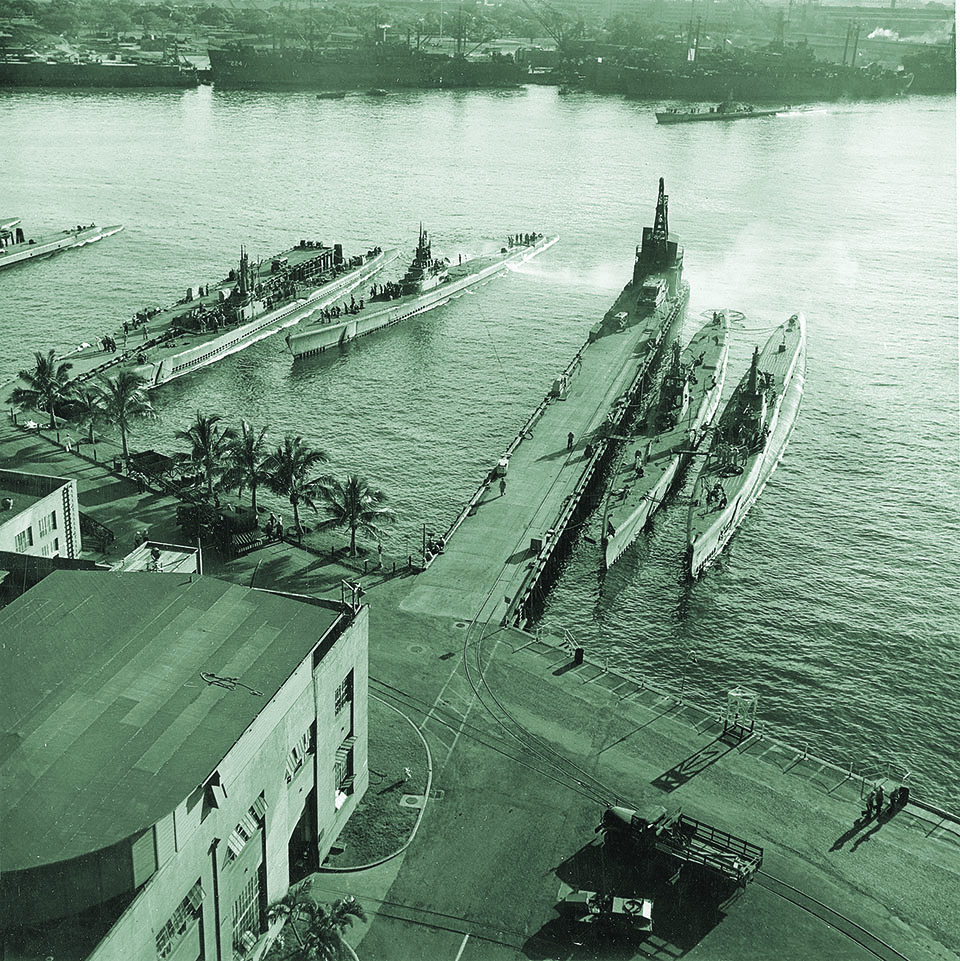

Just past 5 p.m. on November 5, 1943, Sculpin slipped its moorings at Sub Base, Pearl Harbor, and headed southwest. A few days later it reached its assigned area 200 miles east of the enemy naval base at Truk, along the Truk-Tarawa sea lane.

On the night of November 16, as Sculpin patrolled its sector, a crewman handed a decoded message from Admiral Lockwood to Commander Connaway. “ANOTHER HOT ULTRA,” it began. It told him that a Japanese freighter escorted by two destroyers and a light cruiser was headed his direction. It gave him their speed and course, and the convoy’s expected noon positions. “SCULPIN INTERCEPT IF POSSIBLE.”

Connaway shared the dispatch with Cromwell. The two officers agreed that a single merchantman escorted by three warships was exceptional and concluded that it must be carrying unusually valuable cargo, making it all the more worthy of pursuit. Leaning over a chart of the eastern Carolines, Connaway plotted the convoy’s projected route and where Sculpin might best set its trap. He ordered the steersman to head west by north.

Just before midnight on November 18 the radarman called the skipper to the conning tower to show him four blips on his screen, tracking at 14 knots. It was the fast convoy mentioned in the Ultra intercept. Connaway ordered an “end around”—a maneuver where the submarine races ahead on the surface, submerges, and waits for the targets to catch up. At 6:30 the next morning, an hour after sunrise, the boat dived. “Battle stations, submerged,” the skipper ordered. “Up periscope.” He could see the convoy just coming over the horizon. A brief peek, and “down scope.” He repeated the step several times. At this point the enemy was a few thousand yards off—a textbook setup.

On his last peek, though, Connaway saw the convoy suddenly turn toward him. His mind raced. Was it just a normal zig, or had he been spotted? “Take her down!” he ordered. As fireman Joe Baker recalled, “Down we go to about 180 feet and stand by to get worked on. [But the Japanese ships] pass right over the top of us and keep right on going.”

It appeared that Sculpin hadn’t been detected. After an hour submerged, Connaway reckoned it was time to do another end around; he didn’t want to let such a juicy target get away. “Surface!” he ordered. Quartermaster Billie Minor Cooper and executive officer Lieutenant Nelson J. Allen climbed to the bridge and began to sweep the sea with their binoculars. Soon the officer spotted something. “What does this look like to you?” he asked Cooper. “Looks like a crow’s nest,” the QM answered. What they spotted was the mast tops of the Japanese destroyer Yamagumo—a “sleeper” that had dropped back from the convoy to simply wait and see. They told the captain he’d “best take her down.” It was now 7:30. The game was about to begin.

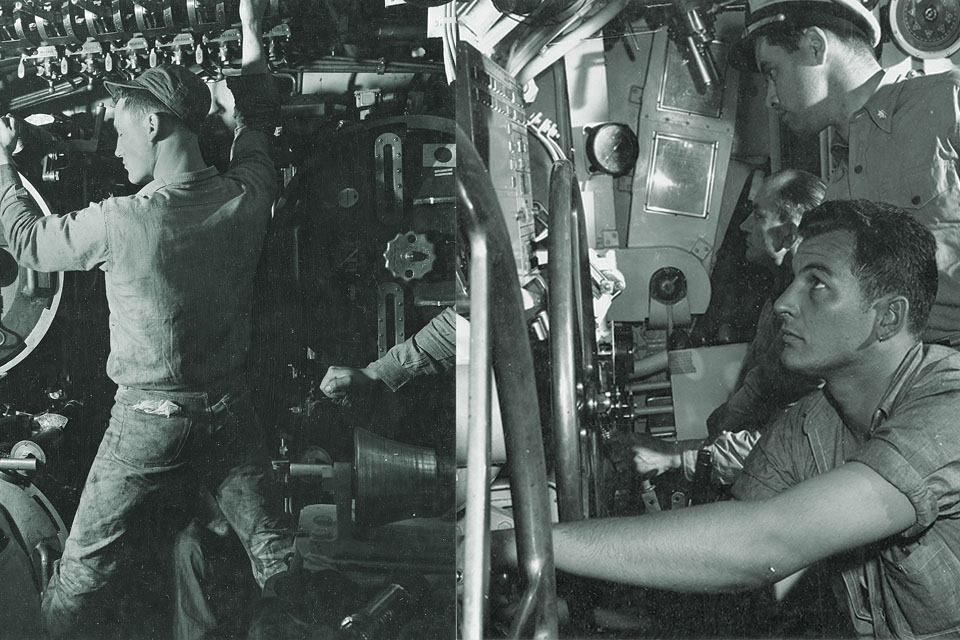

Diving officer George Brown barely succeeded in getting Sculpin down to 130 feet before the destroyer sped overhead, dropping a string of 18 depth charges. “It jarred the hell out of us,” Baker remembered of the attack. The detonations ruptured an engine exhaust valve, causing serious flooding in the aft compartments. An hour later the predator made a second run, dropping another 18 depth charges. Sculpin was so rocked by the concussions that, Brown recalled, “the hands of the depth gauge fell off in front of my face.”

Yamagumo’s battle-tested captain, Lieutenant Commander Ono Shiro, was a canny tactician. Now that he had an American submarine within his grasp, he settled in to patiently, methodically destroy it. At 9:30 a.m. he made his third attack.

The damage continued to mount, with the weight of the water aft tilting the sub to a 30-degree angle. Connaway sent Brown to inspect the situation. Then the skipper, thinking Yamagumo might have given up, ordered periscope depth so he could take another look. Brown’s replacement at the diving station, Ensign Wendell M. Fiedler, a reservist on his first patrol, fumbled and lost control of the boat’s buoyancy; Sculpin’s nose suddenly shot out of the water. The mistake did not go unnoticed by the sharp-eyed lookouts on Yamagumo. The destroyer turned toward the sub while Fiedler desperately struggled to dive the boat. He managed to get it down to 100 feet when, as Joe Baker recalled, “We could hear [Yamagumo’s] screws going right over our heads.” Eighteen more depth charges rained down, wreaking still more havoc.

But then Fiedler could not stop Sculpin’s plunge toward the bottom. The boat reached 700 feet—well in excess of its 250-foot test depth—before George Brown returned to his post, arresting its descent by blowing air into the ballast tanks. Connaway and Cromwell discussed waiting until darkness, still six hours away, before trying to escape from Yamagumo. Captain Ono, though, had other ideas. At 12:30, sensing the time had come to deliver the death blow, he pressed home a final attack on his stricken prey.

Things were looking grim for Sculpin. Temperatures inside the hull had risen to over 115 degrees Fahrenheit, the air was becoming unbreathable, and the crew was unable to stanch the sub’s myriad leaks. Here’s where Connaway’s inexperience showed: he wanted to surface and battle it out with Yamagumo. But Cromwell was adamantly opposed. He believed staying submerged was the boat’s best option. A heated argument ensued. Quartermaster Billie Cooper recalls hearing the senior officer say, “Keep her down or I’ll court-martial your ass when we get back to Pearl!” Connaway was insistent. “No, we’re going to battle surface!” Cromwell retired to the wardroom.

At 1:30 p.m. the submarine surfaced. Ono Shiro and his crew were so startled by the sudden appearance of Sculpin they did not immediately open fire. The sub’s gun crews were anxious to get topside, but Connaway had not issued orders to open the hatch. “I think the skipper had just given up. He knew we didn’t have a chance,” recalled Chief Signalman W. E. “Dinty” Moore. Cooper yelled out, “Give us a fighting chance,” and popped the hatch himself. Sailors poured onto the deck to man the guns. The Americans got off the first shot. It missed—and so did the next seven. When Captain Ono gave the command to fire, Yamagumo let loose with a five-inch salvo. It was wide, but the second made a direct, devastating hit on the conning tower, instantly killing Connaway and three senior officers.

In that terrible moment Lieutenant George Brown became Sculpin’s commander. The first order he gave as a skipper was, “Abandon ship and God have mercy on your souls.” Then he and Chief Philip J. Gabrunas began opening the sea vents to scuttle the sub. John Cromwell came into the control room and calmly told Brown that he had decided to go down with the ship to protect the Ultra secret. Brown was startled, later recalling, “He was afraid the information he possessed might be injurious to his shipmates if the Japanese made him reveal it by torture.” The lieutenant implored him to evacuate, but Cromwell said he had made up his mind “a long time ago.” He wasn’t going to let the enemy even have a shot at him. The last Brown saw of Cromwell he was sitting on an empty 20mm shell container, holding a picture of his wife and children.

Japanese sailors aboard Yamagumo pulled 42 Sculpin crewmen out of the water—and almost immediately threw one badly wounded American back into the sea and to his death. Once aboard, the Americans were herded together at the fantail, their hands tied. The ship sailed to Truk, where guards took the prisoners to an old jail and jammed them into three tiny cells. Brutal interrogations followed—the officers getting the worst of it.

After 10 days of beatings, meager rations, and little water, the Japanese captors divided Sculpin’s 41 remaining crew into two groups and put them aboard a pair of escort carriers, Un’yō and Chūyō, bound for Yokohama. As the ships neared Japan just after midnight on December 4, an American submarine, vectored there by an Ultra intercept, attacked the Chūyō. Despite mountainous seas, two torpedoes found their mark, explosions wrecking the enemy ship. Two more attacks finished it off. “One full day’s work completed,” the skipper cheerfully wrote in his patrol report.

What the captain didn’t know—couldn’t have known—was that there were 21 Americans aboard Chūyō. Motor Machinist’s Mate George Rocek was the only survivor. “I was underwater trying to break the suction and reach the surface. My whole life flashed before me. It was an eerie and serene sensation,” he later recalled. In one of World War II’s many tragic ironies, Sculpin’s survivors died at the hands of their sister ship, USS Sailfish.

The prisoners aboard Un’yō were delivered to Yokohama and sent to Ōfuna, a camp for high-value prisoners, where their captors again subjected them to intense questioning. In early 1945 the 21 remaining Sculpin survivors were transferred to a copper mine in the mountains north of Tokyo. “The work was hard, dirty, and dangerous,” Rocek said.

Their ordeal ended on September 4, 1945, when American troops freed them. Navy intelligence officers debriefed the submariners on Guam, and it was only then that the world learned about the captain who chose to die rather than have American secrets wrung out of him at the hands of a merciless enemy. Had the Japanese succeeded in uncovering the Ultra secret they would have immediately changed their codes and put the U.S. Navy code breakers out of business. By helping to preserve Ultra, Cromwell spared the lives of thousands of Americans.

Admiral Lockwood recommended John Cromwell for the Medal of Honor. In May 1946 the award was presented to his 17-year-old son, Jack. The citation began: “For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty.” Captain Cromwell, it said, had “stoically remained aboard the mortally wounded vessel as she plunged to her death. Preserving the security of his mission, at the cost of his own life, he had served his country as he had served the Navy, with deep integrity and an uncompromising devotion to duty.”

John Cromwell has been honored in many ways: Cromwell Hall at the Groton submarine base, the frigate USS Cromwell, a plaque outside his dorm room at the U.S. Naval Academy. But perhaps the highest honor comes from the people of his hometown, Henry, Illinois.

Each September 11, folks gather at the Cromwell Memorial in Henry’s Central Park to pay tribute on the birthday of their hometown hero. “Destiny touches many men for heroic deeds, but few possess the courage to volunteer their own lives that others may live,” wrote Rear Admiral Frank D. McMullen, then the commander of the Pacific sub fleet, to mark the 1974 dedication of a monument there. “John Philip Cromwell was endowed with such a quality.”

During World War II, 472 Americans were awarded the Medal of Honor. Their extraordinary acts of bravery were performed in the heat of battle; their unhesitating decisions were split-second reactions to immediate threats. They had no time to think about whether they would live or die. Among all those heroes John Philip Cromwell’s sacrifice was unique. He had the luck—or the curse—of deciding his own fate with deliberate forethought. His unhesitating decision was made knowing that his choice meant death. ✯