In the final week of the war in Virginia, small villages, crossroads and railroad depots previously untouched by the fighting took on enormous importance as Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant sought to bring General Robert E. Lee to bay and the Confederate chieftain struggled to escape a Federal encirclement. Among the most important of these newly crucial junctures were the spans at High Bridge crossing over the Appomattox River. These routes would either buy Lee desperately needed time if he possessed them or push the staggering Army of Northern Virginia closer to capitulation if he didn’t.

After Grant finally broke Lee’s overstretched lines on April 2, 1865, his opponent had no choice but to abandon his positions along the Petersburg and Richmond fronts. While his overall aim was to march south and join General Joseph Johnston’s forces in North Carolina, the Confederate commander’s immediate need was to secure the time and space necessary to concentrate and resupply the fragmented Army of Northern Virginia. Lee’s skill in evacuating his forces bought him a day’s lead over Grant’s swarming soldiers, and he paused at Amelia Court House, west of the former Confederate capital, to allow Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s men from north of the James River and Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Richmond garrison to join up with the troops escaping from Petersburg.

Unfortunately for the Rebels, the rations which were expected at Amelia failed to arrive, and Lee’s men were forced to scour the countryside for food. Worse, the time spent attempting to revictual his army erased Lee’s one-day lead and allowed Grant to close up with both the Army of the Potomac and the Army of the James. When Lee pushed westward toward Danville on April 5, hoping to secure rations from Lynchburg via the Danville & Richmond Railroad, he found Federal cavalry in front of him. Unsure if Union infantrymen were there as well, he altered his plan and headed toward Farmville on the South Side Railroad. Once again Lee was faced with the critical problem of outracing Grant’s armies who were constantly harassing his retreating columns. More dangerously, Grant and his lieutenants were striving to get west — in front of Lee — and bring the Virginia campaign to a victorious close.

Events would shortly force the Southern chieftain to search for another means of putting some space between his hungry, dwindling forces and Grant’s legions. Only one route seemed to offer any prospect of success — crossing to the northern side of the Appomattox River by means of the spans at High Bridge and Farmville. With the river between his men and the Yankees, Lee might yet have time to rest, feed and reorganize his army before facing the ultimate challenge of wheeling southward to North Carolina.

Lee’s decision to cross to the opposite side of the Appomattox was necessitated by the disasters which befell the Army of Northern Virginia on April 6. On that day, south of the Appomattox near Little Sailor’s Creek, Federal forces exploited two gaps in Lee’s columns and succeeded in attacking Ewell’s and Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson’s commands — which constituted the center, and weakest, part of the retreating column — from both the southwest and east. After tough initial resistance, Northern numbers overwhelmed the Confederates, and Union troops bagged large numbers of prisoners, including Generals Ewell, Custis Lee, Montgomery Corse and Joseph Kershaw. What was left of the Rebel units fled westward where the van of Lee’s army, Longstreet’s First Corps, had paused.

|

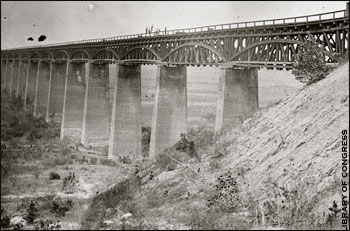

| The crossings at High Bridge, including the railroad bridge and the wagon bridge below it and to the right, spanned the Appomattox River. The Confederates’ inability to destroy both the crossings on April 7, 1865, after the Battle of Sailor’s Creek guaranteed that they would not be able to fend off Grant’s armies. |

Meanwhile, Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, who commanded Lee’s rear guard, was leading his men along the Jamestown Road north of the Little Sailor’s Creek battlefield. Earlier in the day, Ewell and Anderson became concerned that the army wagon train, carrying supplies and ammunition, was slowing their march. To allow the infantry to move more rapidly, the heavy vehicles were directed to take an alternate route north of the army’s path. As the wagons rolled northward across his front, Gordon was forced to halt his troops and let them by. No one thought to inform Gordon which route the army itself was taking, and he mistakenly turned away from Ewell and Anderson and followed the wagons along the Jamestown Road. Unbeknownst to Ewell, the army’s rear guard was no longer behind his men, which set the stage for the Confederate debacle at Sailor’s Creek.

Burdened by the cumbersome wagons, with his troops suffering from a lack of food and rest, Gordon found himself hard pressed by Union Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys’ II Corps. At about 5 p.m., as the Rebels were wrestling the wagons across the boggy ground bordering the northern reaches of Sailor’s Creek, Federal generals Nelson Miles and Philip Regis DeTrobriand, commanding the II Corps’ 1st and 3rd Divisions, respectively, attacked Gordon’s men. The Southerners fell back to high ground behind the creek, though Miles and DeTrobriand captured about 1,700 men and 13 stands of colors, three cannons and more than 300 wagons and ambulances. The action at Lockett’s Farm, as the fight between Gordon and Humphreys became known, was halted by darkness. Gordon then withdrew westward, drawing closer to the Appomattox spans known as High Bridge.

The importance of the Appomattox crossings became increasingly apparent to both Confederate and Union leadership as the events of April 6 unfolded. In the morning, before the Confederates were overrun at Little Sailor’s Creek, both Grant and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade reached the conclusion that Lee was headed toward either Farmville or Lynchburg. To prevent Rebels using the northern (actually western at that point due to a turn in the river) bank of the Appomattox as a shield, Grant ordered Maj. Gen. Edward Ord, commander of the Army of the James, to destroy the river crossings at High Bridge. The trestle, built by the South Side Railroad in 1854, was an engineering marvel of the age. The span extended 2,400 feet and rose 125 feet. Twenty-one brick piers supported the tracks. A smaller wagon bridge ran parallel to the towering railroad trestle, and both bridges offered an escape route across the 75-foot-wide Appomattox River. Theodore Lyman, Meade’s volunteer aide, was suitably impressed when he later came upon the structure. “Nothing can surprise one more,” he wrote, “than a sudden view of this viaduct, in a country like Virginia, where public works are almost unknown….The river itself is very narrow, perhaps 75 feet, but it runs in a fertile valley, a mile in width, part of which is subject to overflow.”

Around 4 a.m., Ord dispatched a raiding column, consisting of the 54th Pennsylvania and 123rd Ohio, plus three companies of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry, with orders to burn the bridges. Ord considered the mission important enough to place his chief of staff, Brevet Brig. Gen. Theodore Read, in command of the strike force. Shortly after Read’s men moved out, however, Lee and Longstreet received reports of Federal cavalry heading toward the spans. Lee was already beginning to think that a shift to the opposite side of the Appomattox might become necessary, and both men recognized how critical possession of the crossings would be. Longstreet quickly dispatched the cavalry units of Brig. Gen. Thomas Rosser and Colonel Thomas Munford to intercept the Yankees. The Union cavalry had to be destroyed, “Old Pete” emphasized to Rosser, exhorting him to finish the job even “if it took the last man of his command.”

Unaware of the Southern horsemen closing fast behind them, the Yankees reached the spans. Read remained with his infantry at a nearby farm while the cavalry, under Colonel Francis Washburn, drove off troops from the 3rd Virginia Reserves who were stationed in two redoubts below the river crossings. Shortly after, Rosser and Munford caught up with the Yankee raiders. They quickly ordered their men to dismount, and the Rebels slammed into Read’s soldiers on their front and right flank. The sound of the fighting reached Washburn, who turned his companies about and hurried back to help Read. The furious collision between the dismounted Southern cavalry and their mounted Yankee counterparts resulted in a savage hand-to-hand fight during which Washburn was shot in the mouth and then slashed across the head with a saber. Confederate Brig. Gen. James Dearing, who had led the assault on Read’s right, was mortally wounded while firing at Read, who also fell dead, possibly from Dearing’s bullet. Dearing became the last Confederate general killed in the war.

Washburn’s charge had been brave but futile, and his men were virtually annihilated. The Federal infantry fell back to the bridges, but surrendered after the Rebels attacked again. Rosser and Munford tallied up their spoils, which included 780 prisoners, six flags, an ambulance and even a brass band. When the Southern cavalrymen trotted back into their camp later in the day, Rosser was riding a fine black horse and carrying a new saber. “It was a gallant fight,” he announced to Longstreet. “This is Read’s horse and this is his saber. Both beauties aren’t they?” More important than the prisoners and trophies was the fact that High Bridge remained in Southern hands, and Lee kept hold of an escape route from the fast deteriorating situation south of the river.

That night, seeing no other way to shake off the Northern pursuit and rest and feed his men, Lee ordered his dwindling army over to the north side of the Appomattox. The decision was reached at a council of war attended by the most senior surviving generals of the Army of Northern Virginia — Longstreet, Gordon, Anderson and Maj. Gen. William “Little Billy” Mahone. Mahone, a railroad man before — and after — the war, was familiar with the South Side line and recommended that the army cross to the bank of the river by means of the spans at Farmville and High Bridge. Lee agreed and orders were issued to transfer the army to the presumed safety of the north bank. Longstreet, Maj. Gen. Harry Heth and Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox, whose men were farthest west, would continue to Farmville where they hoped to receive rations sent from Danville via the South Side Railroad. Once the food was distributed, the troops would cross the Farmville bridges and then burn them. Gordon, Mahone and what was left of Anderson’s Division were to cross at High Bridge, destroy the spans and reunite with Longstreet’s troops who would be waiting on the north bank of the river opposite Farmville. If all went as planned, the withdrawal would be completed before dawn, and the army would link up in the morning, while the Yankees stood frustrated on the south bank staring at the smoldering and ruined bridges and waiting for their pontoons. While it was the longest of long shots and allowed no room for error, Lee might yet make it to Lynchburg or even Roanoke. From there, he could wheel south toward Johnston and North Carolina.

This gambit, however, handed Grant an enormous opportunity. The Federal forces south of the Appomattox River now had a shorter distance to cover in order to reach Appomattox Station, the nearest point where Lee could receive supplies from Lynchburg and possibly steal a march south. If one wing of the Federal army could block Lee at Appomattox, and another pin him down north of the river, the Confederates would be doomed.

The river crossing went largely as planned at Farmville, where Longstreet’s men finally received some rations. Distribution was cut short by the approach of Union troops and the trains bearing the badly needed food were ordered away. Longstreet then directed his men over the river and set the bridges ablaze, successfully preventing the Union VI Corps from following him.

At High Bridge, however, the Confederate plan began to unravel. The crossing was delayed when Anderson, acting on earlier orders to collect stragglers, posted guards at the High Bridge spans, who refused to let Mahone’s men cross. Mahone, who was in almost constant motion throughout the night, rode back and straightened things out, but valuable time was lost. Finally, the tattered gray columns began trudging the walkways over the Appomattox valley. A former governor of Virginia, Henry Wise, led his brigade across the wagon bridge while the remainder of the units followed him or used the walkway on the trestle. Gordon took on the almost hopeless task of organizing the retiring troops by brigades. Though the Confederates still spoke in terms of “brigades,” the word had lost much of its meaning as many of them were smaller than a poorly outfitted regiment should have been. Not only were the units a shadow of their former selves, but most of the soldiers had been worn to a frazzle by the continuous marching, fighting and lack of food. Some of the men making their way across the wagon span were so exhausted that they fell asleep while walking only to be awakened when they hit the ground.

In the early morning hours of April 7, while their commands staggered across the Appomattox River, Mahone, Anderson and Gordon began to discuss the long-dreaded topic of surrender. After a brief conference the generals concurred that capitulation seemed increasingly likely, if not inevitable. Since Anderson had served under Longstreet, and temporarily led his corps, Mahone and Gordon convinced him to go to “Old Pete” and convey their opinion that resistance was no longer possible.

As the meeting ended, Mahone reminded Gordon that an order was needed for Colonel Thomas M. Talcott of the engineers to destroy the High Bridge crossings. Gordon sent no order and probably expected Mahone, who commanded the rear guard, to take care of it. Back at the bridges, the engineers preparing to ignite the spans anxiously awaited their orders. But as the dark hours slipped away and no word arrived, they sent out parties searching for Mahone. They finally met up with him as he was returning to High Bridge from a night of conferences and scouting. With the first streaks of dawn beginning to color the sky, the wiry general quickly ordered the torching of one span of the railway bridge and the complete destruction of the wagon bridge.

The burning detail, under the immediate command of Captain William R. Johnson, soon set the railroad span blazing, but the hardwood on the wagon bridge was tougher and took flame reluctantly. In any event, the engineers were too late. The disorganization — and probably mental fatigue — of the Confederate command had fatally delayed the destruction of the bridges. As the Confederates belatedly began to destroy the crossings, the Union 2nd Division of the II Corps rushed to the scene.

Though the man who led the 2nd Division onto the field had been in command less than a day, he was well-known in the Army of the Potomac — and probably among many in the Army of Northern Virginia as well. Sometimes called the “Boy General” due to his lithe frame and beardless face, 29-year-old Maj. Gen. Francis Channing Barlow had carved out a reputation as one of the most pugnacious generals in the Army, rising from private to major general and seeing action in almost all the major battles in Virginia. But even his driven personality was sapped by the incessant fighting of the Overland-Petersburg campaign, and physical and mental exhaustion forced him to take convalescent leave the previous August. But with the last campaign of the war clearly at hand, a rested Barlow reported for duty on April 1 and five days later he took command of the 2nd Division.

When Barlow arrived at Amelia Springs to assume command of his new unit he became its third commander in 24 hours. On the morning of April 6, Humphreys set out to inspect the 2nd Division’s preparations to move forward against Lee’s fleeing troops. Instead of finding the regiments ready to march, the division lay in its camps with no orders given to prepare to advance. Infuriated, Humphreys rode to the headquarters of division commander Brig. Gen. William Hays, where he found everyone asleep. Humphreys immediately relieved Hays of command and sent him off to the artillery reserve. He then installed Maj. Gen. Thomas Smyth as the new division commander. Smyth was a seasoned officer who had commanded the Irish Brigade under Barlow at the Wilderness, but had transferred back to the 2nd Division before Spotsylvania. When Barlow caught up with the army later in the day and took command of the division, Smyth resumed command of the 3rd Brigade. Barlow’s energy was immediately felt, and the division was quickly on the march against the retreating Rebels. The 2nd Division was on Miles’ right flank during the fighting at Lockett’s Farm, but remained unengaged in the fight.

Around 5:30 on the morning of the 7th, the II Corps left its lines around Lockett’s Farm and renewed its pursuit of Gordon’s forces. Barlow’s division was on the corps’ right, or northernmost, flank closest to High Bridge, and he was determined to not let the Rebels escape. The 2nd Division reached High Bridge at 7 a.m., just as the last Confederates to cross the river blew up one of the two redoubts covering the spans. The tall railroad trestle was already blazing, and Barlow ordered Colonel Thomas L. Livermore of the II Corps staff and his engineers to save it. Engaging in a high wire act 125 feet above the river, Livermore’s pioneers managed to save part of the bridge, but three sections were already gone and a fourth soon gave way, making it unusable as a crossing. Seizing the smaller wagon bridge, which was burning but still intact, was essential if Lee was to be captured. If the II Corps failed to get across the river, Lee would have gained the breathing space he desperately needed to continue his resistance.

Eight months rest and recuperation had not dulled Barlow’s military skills. While Livermore and his detachment struggled to salvage the burning railroad bridge, Barlow ordered his 1st Brigade, led by Colonel I.W. Starbird of the 19th Maine, to seize the wagon bridge and hold it. The Down East troops raced across the span and secured a bridgehead on the north side of the river, though Starbird himself fell seriously wounded in the assault. While Starbird’s skirmishers laid down a covering fire, the remainder of the 19th Maine fought the fire with blankets and canteens. Colonel William A. Olmstead then brought the rest of the brigade across for support, and sent two regiments along the railroad as skirmishers and flankers.

Clearly realizing the stakes, Mahone threw a counterattack against the isolated Yankees on the west bank, and the Rebels began to gain ground, pressing the Federals back toward the crucial structure. As the struggle around the bridgehead grew desperate, Miles’ division reached the field, and Union artillery was soon hurling shells into the charging Southerners. Barlow’s 3rd Brigade, under Smyth, then surged across the bridge and broke the Confederate counterattack. With Miles’ men now reinforcing Barlow, Mahone called off his assault and resumed his retreat toward Longstreet’s lines. Counting up his spoils, Barlow found he had captured 18 abandoned guns and several hundred Enfield rifles. Significantly more important, the capture of the bridge meant Lee would have no respite from the relentless Union pressure.

Once his entire corps was across the river, Humphreys sent Barlow after Gordon’s column, which was moving southwest along the railroad track toward Farmville. The II Corps’ other two divisions followed a slightly northwest course in pursuit of Mahone. Barlow caught up with the Confederates at the intersection of the High Bridge and Farmville roads, where they had paused to entrench. The Rebels were preparing to evacuate the position when Barlow struck their lines, cutting off a wagon train of 135 vehicles, which he promptly set ablaze. But Lee’s men, dazed by fatigue and hunger, were still capable of a fight. At the beginning of the attack, Smyth, who led his skirmish line to within 50 yards of Gordon’s rear guard, was shot in the face by a sharpshooter. The bullet entered above the mouth, fractured several cervical vertebrae, and forced a piece of bone against his spine. He was carried off the field totally paralyzed. Smyth succumbed to his wound two days later, unaware of Lee’s imminent surrender, and earned the unfortunate distinction of being the last Federal general killed in the war. In the confusion following Smyth’s wounding, an advance line of 103 men from the 7th Michigan and 59th New York were captured by North Carolina troops.

But Barlow quickly redressed his lines and was again pushing after the retreating Southerners. He followed the Confederates as far as the north bank of the Appomattox facing Farmville when orders from Humphreys forced him to abandon his pursuit. In his absence, the main body of the II Corps had run into stiffening resistance at Cumberland Church, and the 2nd Division was called back for support. Though they had no way of knowing it at the time, the fighting at High Bridge, the Farmville Road and Cumberland Church was the last the II Corps would see in the war. On the following day, Humphreys advanced without making serious contact with the retreating Confederates. As the Federals drove inexorably westward, rumors of a truce began to spread. Major General Philip Sheridan and Ord had beaten Lee to Appomattox Station. Blocked to the south and southwest, hemmed in from the east, with nothing in the way of supplies or hope to the north, Lee surrendered on April 9.

Whatever dim hope Lee retained for shaking off his pursuers and finding a place to move south died at High Bridge. Instead of buying time and space, the Confederates were constantly pressed and harried, unable to move effectively due to the necessity of fighting off attacks. High Bridge tied one string on the box Grant was preparing for Lee. The arrival of Union forces at Appomattox Station later tied the other. Unable to move forward or back, his men falling in battle, dropping by the wayside from exhaustion or surrendering, Lee submitted to the inevitable. While it seems impossible Lee could have prolonged the campaign much longer, Humphreys believed the fighting at High Bridge shortened the war in Virginia by at least a few days. Had Barlow not seized the bridges, he wrote, Lee “could have reached New Store that night, Appomattox Station on the afternoon of the 8th, obtained rations there and moved towards Lynchburg. A march the next day, the 9th, would have brought him to Lynchburg.” The Federal success at High Bridge made that impossible, and the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia inevitable.

This article was written by Richard F. Welch and originally published in the March/April 2007 issue of Civil War Times Magazine. For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!