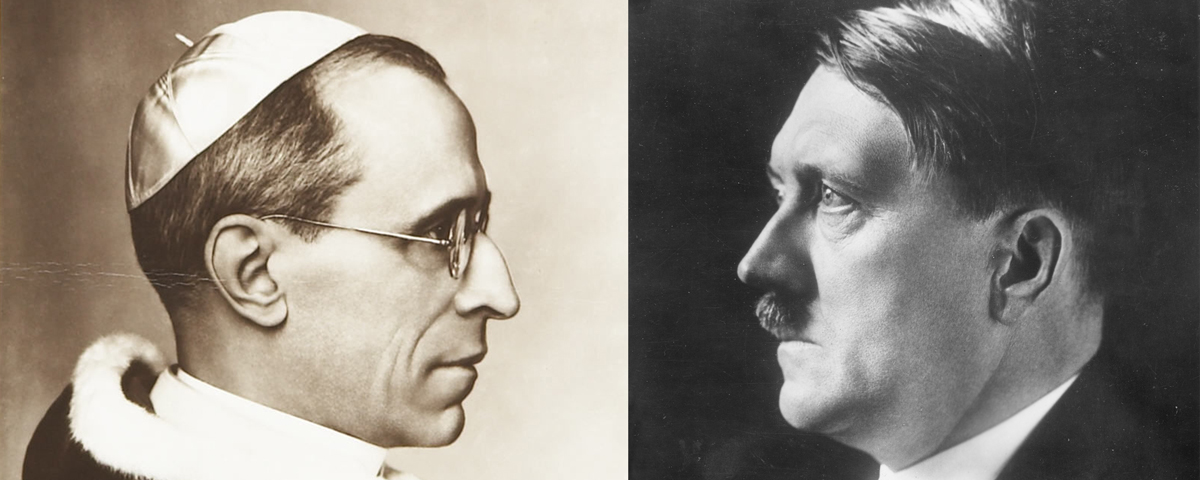

Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War Against Hitler, by Mark Riebling, Basic Books, New York, 2015, $29.99

Pius XII, who reigned from 1939 to his death in 1958, was among the most controversial popes of modern times. Critics maintain he took his job too literally, emphasizing his duty to preserve the Roman Catholic Church and remain above politics when he should have assumed moral leadership to actively fight Nazism and shield its victims. But in this revealing history of Pius’ wartime dealings with the German resistance to Nazi rule, Journalist Riebling makes a case the pope didn’t do badly.

Pius genuinely disliked Adolf Hitler. The Holocaust preoccupies historians, but Hitler also oversaw a vicious persecution of Catholics. Most readers recall the 1934 “Night of the Long Knives” purge, when the Nazi leader had many of his rivals murdered. The list of victims included influential Catholic politicians, magazine editors and even the leader of the Catholic Youth Sports Association. In the wake of the 1939 conquest of Poland, the Nazis launched a massive attack on its Catholics, executing or deporting thousands of clergy members.

Despite the book’s title there was no combat, but Pius nonetheless turns out to have been a pivotal figure in the resistance to Hitler. There was no shortage of Nazi leaders anxious to get rid of the führer. When he threatened to invade Czechoslovakia in 1938, they were certain Germany would lose the war that would follow. A planned coup when Hitler made his move fell apart when British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain agreed to dismember Czechoslovakia.

The Wehrmacht had little trouble conquering Poland, but Germany’s military leaders largely opposed invading France, then regarded as Europe’s leading power. While they considered deposing Hitler, many worried the Allies would take advantage of a leaderless Germany. They approached Pius XII, who agreed to vouch for them and act as an intermediary in negotiations with the Allies.

For the remainder of the war a half-dozen lay and ordained German Catholics kept in touch with the resistance in Berlin, traveling to and from Rome to inform the pope and relay his encouragement. Pius passed intelligence to Allied diplomats, who remained skeptical even when he provided such useful details as the dates of German offensives.

Readers will be surprised at the steady stream of anti-Hitler conspiracies, several of which reached the point where dates were set and bombs assembled. It’s no secret that all attempts failed, and the near miss on July 20, 1944, prompted a flurry of arrests, torture and executions, which Riebling describes in gruesome detail.

Despite knowing the outcome, readers will admire the author’s effort and won’t find it entirely depressing. The pope’s emissaries took terrible risks, and most died horrible deaths, but a few survived and went on to distinguished postwar careers in government and the church hierarchy.

—Mike Oppenheim