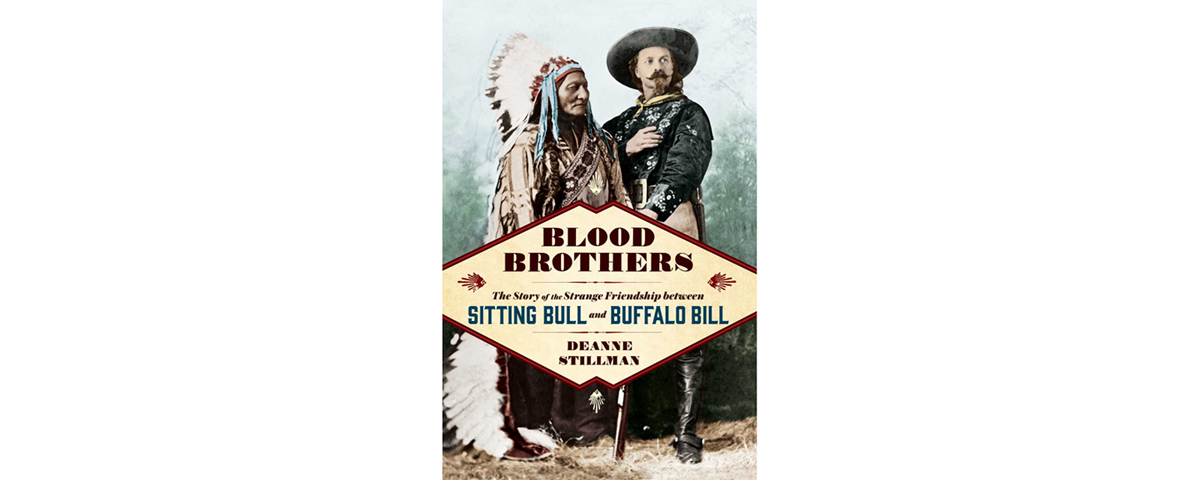

Blood Brothers: The Story of the Strange Friendship Between Sitting Bull and Buffalo Bill, by Deanne Stillman, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2017, $27

Their story might be well known to readers of this magazine and such informative books as Robert Utley’s The Lance and the Shield and Louis Warren’s Buffalo Bill’s America. No matter. Some of us can’t get enough of this pair, and to this day the Sitting Bull–Buffalo Bill Cody alliance still seems incredible. One man sought to be left to roam freely in the northern Plains and, when pressed, to kill white soldiers (though he was no longer an active warrior when George Custer fell at the Little Bighorn in 1876). The other was an Army scout who took an Indian scalp for Custer and then went on to become arguably the best showman America has ever known.

They shared a love of horses and freedom but didn’t actually see that much of one another. They came together briefly when Sitting Bull joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1885, and they seemed to find mutual respect. “They were joined in ways that could not be publicized or spoken of,” Deanne Stillman writes. “They shared something that was written in their blood perhaps, in the blood of the buffalo, whose name was linked to theirs.” Unfortunately, necessity compels the author to speculate about the pair’s supposedly deep connection. In many ways the bond between Sitting Bull and Annie Oakley is more engaging, and Stillman devotes much attention to it.

Five years after Sitting Bull left Cody’s Wild West, Bull and Bill just missed connecting at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, where the former lived and then died when the Indian police came for him during the Ghost Dance trouble. If the two men had reunited in December 1890, could Cody have saved Bull’s life? Stillman admits the question is unanswerable (though she suggests Cody himself might have died). “But this most horrific event should not be seen as a near-miss between the two unlikely friends,” she adds. “At the time of the ambush there was an unexpected convergence of their lives in a way that brings a moment of grace, wrenching though it may be.” When the shooting erupted at the great medicine man’s cabin, the horse Buffalo Bill had given Sitting Bull five years earlier started to prance in a circle, paw the ground and rear up as if performing in the arena. And so it goes—a nice story amid tragedy that would soon expand with the horror later that month at Wounded Knee.

Stillman refers to Sitting Bull as “our great Native American patriot” and seems to think more highly of him than Buffalo Bill, but the two get equal time in this engaging book. Some readers won’t learn much new about either man, but Stillman uses her sources well and writes with a flourish worthy of two legends.

—Editor