Deputy U.S. marshals were responsible for maintaining law and order over tens of thousands of square miles in the Western territories. A federal marshal could appoint as many deputies as he saw fit to carry out a wide range of duties, from serving subpoenas and executing warrants to investigating crimes and capturing outlaws.

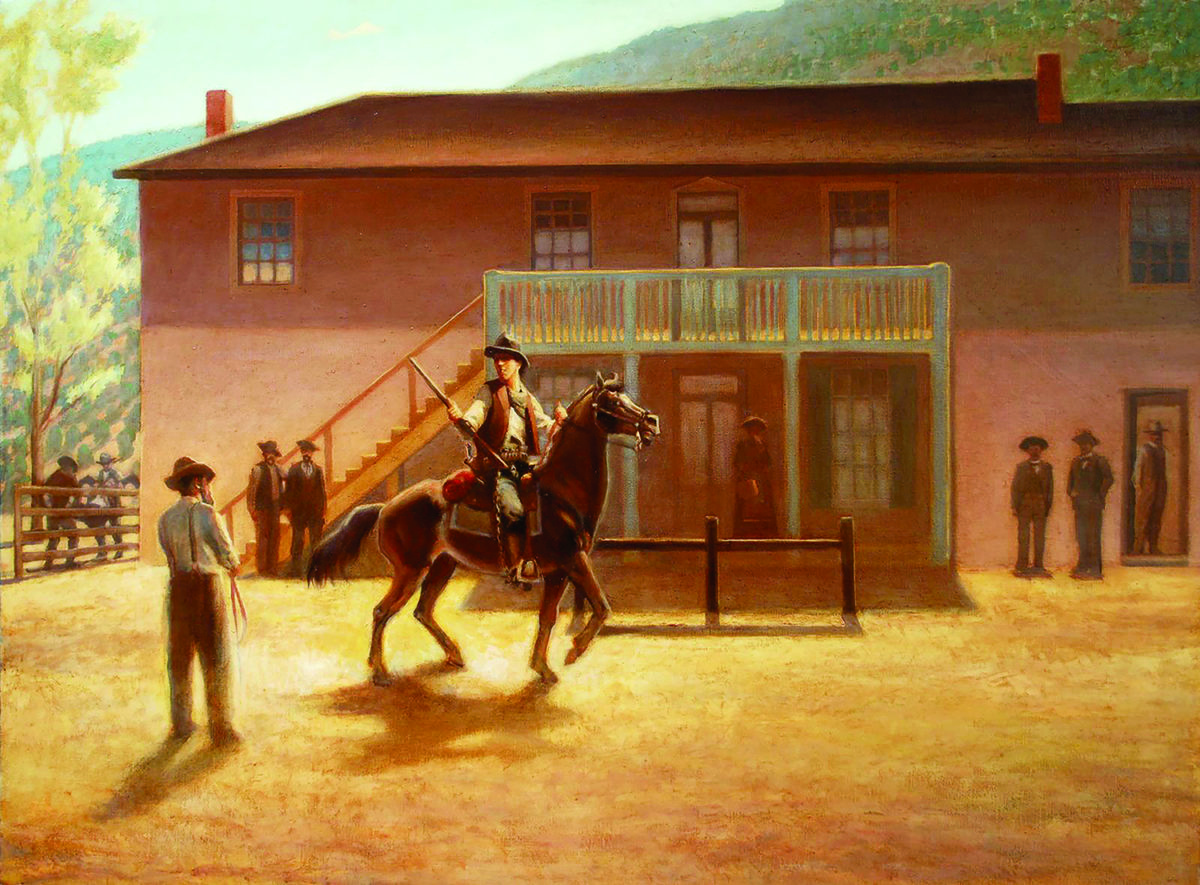

These symbols of Western frontier justice have been portrayed both as heroes and villains, but most of the deputies were just ordinary men trying to do difficult jobs. During the Lincoln County War in New Mexico Territory, which began in 1878, deputy U.S. marshals served on both sides.

What started as a power struggle between two rival factions of ranching and mercantile stores eventually dragged the U.S. Marshals Service into its quarrels and gunfights.

Recommended for you

John E. Sherman Jr., a nephew of Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman, had been the U.S. marshal for New Mexico Territory since his Senate confirmation on May 24, 1876. Upon arriving in Santa Fe, he had spent much of his initial time arranging the transport of prisoners to Fort Leavenworth, Kan., or Jefferson City, Mo. The few experienced deputies available to him were spread across the territory.

In 1878, he realized he needed help in the Lincoln County area, but finding local deputies with the proper background and no hidden agendas proved challenging. He decided to employ a number of former soldiers and adventurers in the area.

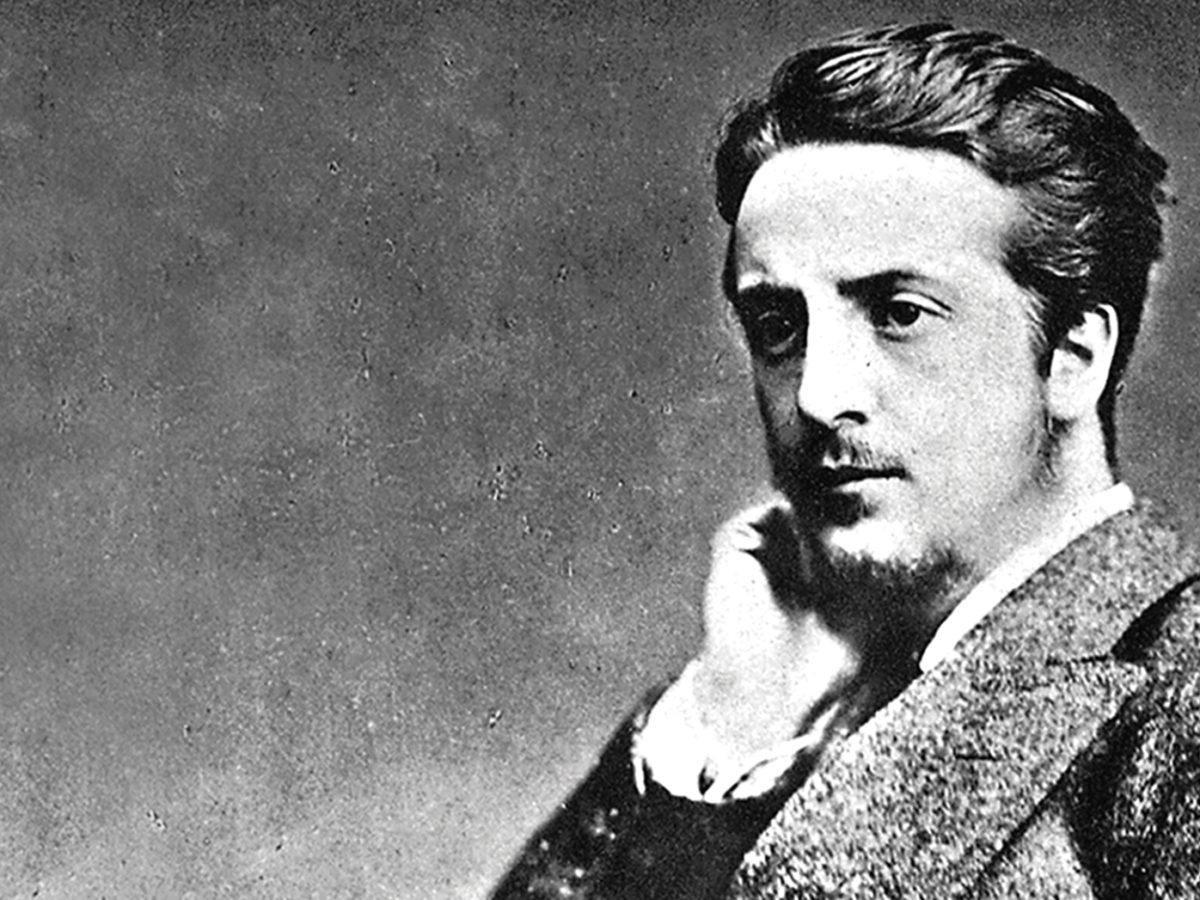

One of the men who Sherman appointed U.S. deputy marshal was Robert Widenmann, the son of a Michigan businessman and personal friend of U.S. Interior Secretary Carl Schurz. Widenmann quickly made friends, and he found one in British subject John H. Tunstall. In early 1877, Tunstall moved to the Lincoln County area and invested in the burgeoning cattle trade. Widenmann soon followed.

Tunstall and Widenmann learned that the cattle trade in this part of New Mexico Territory was a power struggle between cattle baron John Chisum and entrepreneurs Lawrence Murphy and James J. Dolan. Tunstall and many newly settled ranchers allied with the Chisum faction, while lawmakers of the territory, particularly Governor Samuel Axtell, backed Murphy and Dolan. The territorial lawmakers, collectively called the Santa Fe Ring, put U.S. Marshal Sherman in an awkward position.

slaying triggers lincoln county war

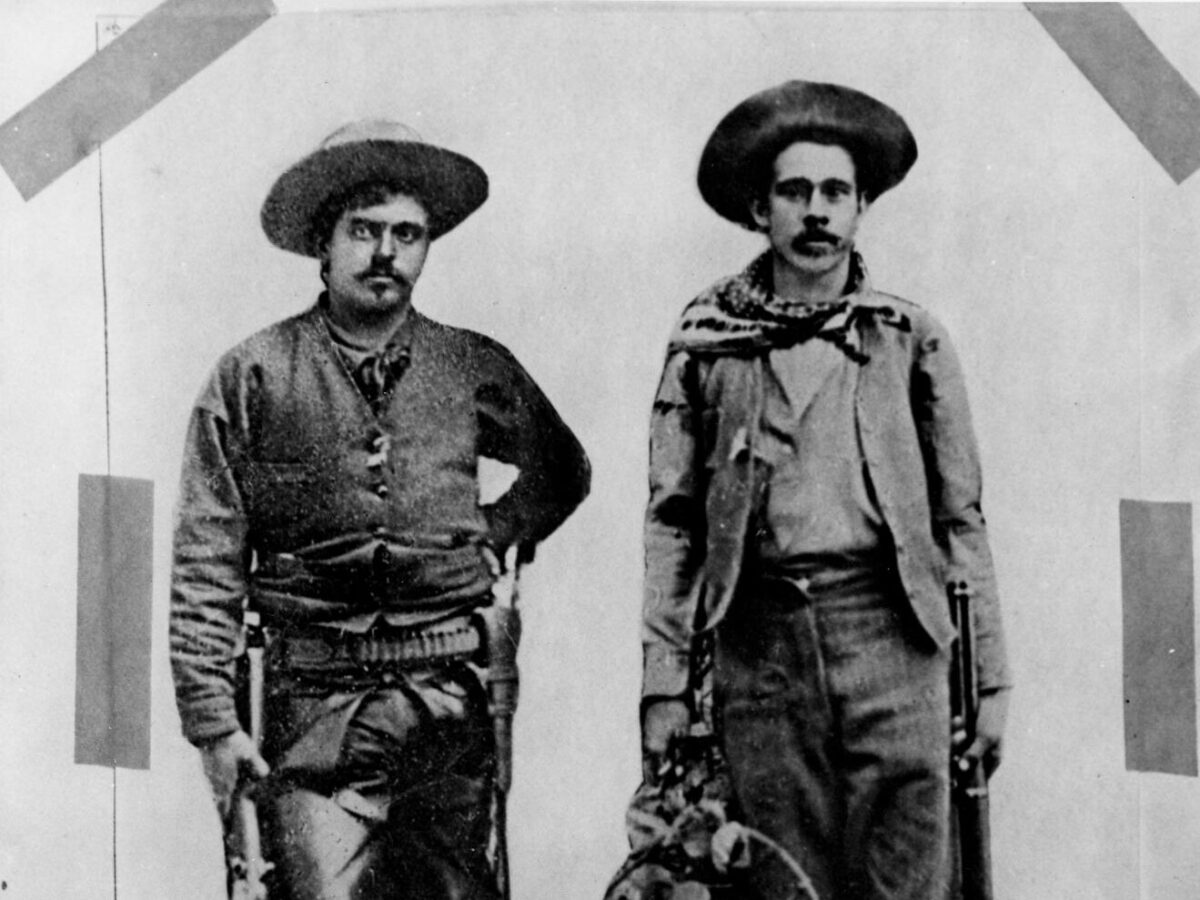

Violence in the region broke out when a subposse allied with Dolan rode down Tunstall in the hills of Lincoln County on February 18, 1878. Several of the men filled the Englishman with shot. Widenmann and a youthful ranch hand named William Bonney, best known today as Billy the Kid, were nearby to witness much of the commotion, but they escaped Tunstall’s fate.

The death of Tunstall triggered the Lincoln County War and brought the marshals into the region’s power struggle. After securing a position as deputy U.S. marshal, Widenmann immediately set out to find the members of the subposse, notably Jesse Evans, a ne’er-do-well from Texas. Marshal Sherman probably misunderstood Widenmann’s only agenda when the deputy requested soldiers from nearby Fort Stanton to serve in a posse to find the murderers at the Dolan residence and store in Lincoln.

On February 23, Deputy Widenmann, Bonney, cowhand Fred Waite and a small number of soldiers and civilians searched the desired buildings but couldn’t find any of the wanted men. As a deputy marshal, Widenmann had it within his power to deputize men to form a posse, and Bonney and Waite must have been two of the men he deputized. A March 8, 1878, letter from Sherman to Colonel Edward Hatch, commander of the Military District of New Mexico, mentioned Widenmann’s posse:

Sir:

I have the honor to again state that I am unable to execute the processes of the U.S. Dist Courts in the County of Lincoln, with the civil machinery under my control, and I most respectfully request that a detachment of U.S. troops not exceeding three (3) companies, be furnished me as Marshal with instructions to act in cooperation with a civil posse under direct command of U.S. Deputy Marshal, R.A. Widenmann, for the purpose of arresting and bringing to jail, the bodies of Jesse Evans, Frank Baker, Thomas Hill, Nicolas Provencio, and Geo. Davis, indicted at the last term of Court held at La Missella [sic] November 1877. Special instructions will be sent Widenmann, to employ these troops only for the arrest of the above mentioned desperadoes.

Very respectfully

John Sherman Jr.

U.S.M.

billy the kid becomes deputized posseman

A civil posse consists of nonmilitary members. Deputation routinely took place prior to the event and lasted the period needed to meet its goal or capture the subject. In order to participate in the search, Billy the Kid must have become a federally deputized posseman on February 23 and possibly for seven additional days. He was not in federal capacity prior to the 23rd. Several letters support the deputation. After Widenmann approached Captain George Purrington at Fort Stanton on February 20, the officer wrote: “….Mr Widenmann again made application for troops to arrest Evans Baker Hill and others whom he asserted were at the store and residence of J.J. Dolan and Co. in the town of Lincoln. The house was surrounded at night by the troops and searched by Widenmann and citizens under him.”

A controversial document assigning this posse to county officials was an unsigned deposition by Lincoln County Deputy Atanacio Martinez. It mentioned a civil posse under his authority that searched buildings in Lincoln during the same time period. However, this was packaged with the collected reports of lawyer Frank Angel, a special agent dispatched to New Mexico Territory to investigate the Lincoln County atrocities.

The deposition must be regarded as suspicious for several reasons. Angel investigated months later, after further violence between the factions. Any involvement by a deputy U.S. marshal favoring either side promised embarrassment. Most important, the deposition was unsigned and therefore invalid as physical evidence.

An April 3, 1878, letter from Marshal Sherman to U.S. Attorney General Charles Devens noted that Frank Baker and Thomas Hill died while resisting officers in their official duties. Baker, along with William Morton and William McCloskey, was executed on March 9 by Billy the Kid and other supporters of the late Tunstall — the so-called Regulators. It follows that the Kid considered himself a local lawman at the time of Baker’s death, and that Sherman saw it that way, too.

On the same day as those killings, Governor Samuel Axtell proclaimed that he had relieved Widenmann of his duties as deputy marshal. But Widenmann protested his innocence, and Sherman reinstated him in late March. In fact, Sherman continued to call Widenmann a deputy marshal even after the April 1 shooting of Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady (who earlier had refused to arrest Tunstall’s murderers). In an April 8, 1878, letter to Lt. Col. Nathaniel Dudley at Fort Stanton, Sherman announced that Jesse Evans was finally captured, and the marshal signed the letter “John Sherman jr for R.A. Widenmann Deputy.”

But Widenmann’s downfall was coming because Brady was not only the county sheriff but also a special deputy U.S. marshal. The Dolan supporter had attained that latter position sometime in early 1878. Axtell utilized Brady to curb Widenmann’s powers and detain him, while the military was used to enforce new warrants against the key Chisum ally, lawyer Alexander McSween. The sheriff was legally pursuing McSween on April 1 when he was killed in a shootout in the streets of Lincoln. Both Deputy Widenmann and Bonney were present. If there was no posse officially recorded in the McSween faction that day, there was one in fact. Therefore, at the moment of Brady’s death, there were two posses, one on each side, and deputy U.S. marshals serving on both sides. On the Dolan side, Lincoln County Deputy George Hindman was also a special deputy U.S. Marshal, and, like Brady, he was killed on the 1st.

In a November 20, 1882, letter to Attorney General Harris Brewster, Sherman sent in his final expense report. He mentioned that voucher No. 7 was for $365, adding: “This expense was incurred by direction of Attorney General Devens, at the request, I think, of the British Minister, in the investigation of the murder of one Tunstel [sic], a British subject, and also of the murder of Deputy Marshals William Brady and George Hindman in Lincoln County, New Mexico.”

Although Billy the Kid was accused of killing Brady, and Widenmann had not likely killed Brady or Hindman, the Dolan forces came after him. Widenmann was imprisoned at Fort Stanton at his own request, since he felt safer in military custody rather than in the hands of Lincoln County Deputy George W. Peppin.

line of sheriffs serve as marshals

Meanwhile, the Lincoln County War continued, with U.S. Marshal Sherman continuing to draw deputies from the Lincoln County’s Sheriff Office. Brady’s successors as sheriff — John Copeland, Peppin, George Kimbrell and Pat Garrett — all doubled as special deputy U.S. marshals. The arrangement allowed Sherman to distance himself from both the violence and the politics of the conflict. When Peppin took over in June 1878, he obtained arrest warrants for 10 men, including “William Bruner; alias Kid, alias Antrim, alias The Kid.” He vigorously went after those named, and even asked the military for aid and a howitzer to capture them. His request led to the Posse Comitatus Act of June 18, 1878, that forbade use of the military by lawmen unless authorized by the Constitution or act of Congress. Despite that act, Dudley aided Peppin, and the results were bloody — the July 19 burning of McSween’s house and the shooting of the lawyer and five others (though not Billy the Kid, who escaped).

By early 1879, Peppin was out of the picture and Kimbrell was both sheriff and special deputy U.S. marshal. Billy the Kid unsuccessfully sought a pardon from new Governor Lew Wallace, then withdrew from the area. He soon became a wanted man in the territory for rustling and counterfeiting near his old stamping grounds. In October 1880, Treasury Agent Azariah F. Wild arrived in Lincoln from New Orleans to investigate counterfeiting operations in that town and in White Oaks. In a report that month, he noted: “There is an outlaw in the mountains here who came here from Arizona after committing a murder there named William Antrim alias Wm Bonney alias Billy the Kid with whom these cattle thieves meet, and by many it is believed that they [the cattle thieves] receive the Counterfeit money. I have found no evidence thus far to support their suspicions.”

Special Operative Wild used deputies to assist him, knowing that it was the U.S. marshals who formerly executed warrants related to counterfeiting prior to the creation of the Secret Service. Robert Olinger, deputized in April 1880, and John Hurley, a former soldier living at Fort Stanton prior to his appointment as deputy U.S. marshal, helped Wild. These appointments, unlike the naming of possemen (such as Billy the Kid back in February 1878), required Marshal Sherman’s signature. In November 1880, former cattle driver Pat Garrett joined the group. After defeating Kimbrell that month in the election for sheriff, Garrett was appointed deputy sheriff and was basically running the show until he officially became sheriff on January 1, 1881. Raids by separate posses led by Olinger and Hurley succeeded in shutting down the counterfeiters.

“Deputy U.S. Marshals who have been appointed on my request have now in their hands…about fourteen criminals,” Wild reported on November 27, 1880.

Billy the Kid and other outlaws were still on the loose, though, so the hunt continued. On December 23, 1880, the Kid surrendered to a Garrett-led posse at Stinking Springs, east of Fort Sumner. Garrett had not officially been made a deputy marshal, although he was so called by Wild. The treasury agent explained in a January 3, 1881, report to Secret Service Chief James Brooks: “I will respectfully state that I applied to Marshal Sherman to appoint P.F. Garrett as Deputy Marshal to which he paid no attention. I was in great need of Mr Garrett at that time and took one of the Commissions Sherman sent to John Hurley — he having sent two — and substituted the name of P.F. Garrett the very man who has rendered the Government such valuable service in killing and arresting these men who I was in pursuit [of].”

Wild was concerned because the deputy U.S. marshal commissions expired on January 1, 1881. He was particularly worried about the “deputation” of Garrett and wanted to ensure it. Wild turned to U.S. Attorney Sidney Barnes, who shared Wild’s enthusiasm for the deputations, as he would prosecute the captured men. Barnes sent Sherman a telegram to authorize renewal deputations for all under his direction. Garrett officially became a special deputy U.S. marshal in January, but at the time he captured the Kid, it could be argued that he had been only a posseman at best (in which case, it could be said that a posseman, Garrett, under Special Deputy Kimbrell, captured a former posseman, William Bonney, at Stinking Springs). Perhaps more would have been made of Wild’s improper use of authority had Garrett not succeeded in capturing Billy.

Wild left New Mexico Territory, mission accomplished, and Garrett, based in Lincoln, thrived in his dual roles of county sheriff and special deputy U.S. marshal. Deputies (including Chief Deputy U.S. Marshal Tony Neis) and guards transported Billy the Kid from jails in Las Vegas, Santa Fe and Mesilla. While in the Santa Fe jail, the Kid complained in a March 4, 1881, letter to Governor Wallace that Marshal Sherman allowed “every stranger that comes to see me, but will not let single one of my friends in, not even an Attorney.”

Billy the kid captured but escapes

On April 13, 1881, Judge Warren Bristol in Mesilla pronounced a death sentence for the outlaw, and Deputy U.S. Marshal Olinger brought him back to Lincoln. The Kid was now Sheriff Garrett’s prisoner again, and he was kept in restraints at the Lincoln County Courthouse. On April 28, Garrett was out of town collecting taxes, so Olinger and guard J.W. Bell were watching the prisoner. While the overbearing Olinger was eating his supper across the street, the Kid escaped his restraints and killed Bell, with some regret because Bell had treated him right. Minutes later, he kneeled in the courthouse window and shot down the returning Olinger with no regrets. The Kid made good his escape, according to one later account, on Garrett’s own horse.

Garrett, known as sheriff but still also a special deputy U.S. marshal, pursued Billy the Kid for several months after the deaths of Olinger and Bell. It was in the middle of July that Garrett and his deputies found Billy at old Fort Sumner, and Garrett shot the Kid dead in the dark bedroom of one Pete Maxwell. That traditional account — as told by Garrett himself (with the help of a ghostwriter) in The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid — has been questioned many times over the years, with some accounts suggesting that the Kid got away to live another day or decades, and others indicating that somebody else besides the Kid died in Maxwell’s bedroom. In any case, the criminal career of Billy the Kid was over, and the Lincoln County War, though it had petered out some time earlier, was now ended.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The fate of the marshals involved in the Lincoln County War was varied. U.S. Marshal Sherman resigned on March 23, 1882, and returned east. During his stint as marshal, some of the known deputies who served under him in Lincoln County were Pat Garrett, John Hurley, George Peppin, George Kimbrell, Robert Widenmann, John Copeland, Tony Neis, Robert Olinger, William Brady and George Hindman. With the exception of Widenmann and perhaps Copeland, all these known deputies were allied with or favored the Murphy-Dolan faction during the Lincoln County troubles. Garrett, of course, achieved everlasting fame for shooting Billy the Kid and was himself shot to death in a 1908 dispute near Las Cruces, New Mexico Territory. Deputy Hurley met his end in a gunfight with a rustler near Las Vegas, New Mexico Territory, in January 1885. Widenmann’s post–New Mexico career took him to Great Britain, where he visited Tunstall’s family, and to Haverstraw, N.Y., where he died on April 17, 1930. According to his daughter, Widenmann lived in fear of his life for many years because of his role in the Lincoln County War and in bucking such powerful New Mexico politicians as Stephen B. Elkins.

There was plenty of confusion in the roles of marshals in the Lincoln County War. While Marshal Sherman was blamed for inaction, the scarce number of available deputies, caution in a politically divided area and the poor communication with Washington officials all played a hand in his behavior. He was constantly manipulated by those around him who had agendas — Wild, Barnes, Axtell and Widenmann. Both sides in the Lincoln County War felt they had lawful intentions, even that one-time posseman Billy the Kid.

epilogue

Written deputations of federal (or marshals) possemen are rare. More likely to be found are some notation of deputation in a list or register used in reimbursement from the Department of Justice. But in Billy the Kid’s case, there is little chance that any such notation exists. The references in official letters from U.S. Marshal John Sherman establish the Kid’s tie with the position of posseman.

Since Deputy U.S. Marshal Robert Widenmann deputized the Kid, I went to the few known places in the United States that contain collections with papers written by or about Widenmann. I found several interesting things, but no personal papers and nothing about the old deputy marshal’s hiring of the Kid. Next, I located a grandson, who filled me in on some of Widenmann’s post-New Mexico movements, such as his visiting with John Tunstall descendants in England and his becoming director of the Haverstraw Light and Fuel Gas Company in Rockland County, N.Y. The grandson knew of no personal papers. In an article published by historian Bruce T. Ellis in the July 1975 New Mexico Historical Review, Robert Widenmann’s daughter Elsie mentioned some papers from the New Mexico years that she has seen inside a wrapper. However, when she went to retrieve the papers following her father’s death in 1930, only the wrapper remained.

The old Widenmann house in Haverstraw, where Elsie cared for her father until his death, no longer stands, having been leveled for new construction. If Widenmann indeed did have personal papers about his time in New Mexico, they are either in private hands or lost forever. —D.S.T.

Virginia author David S. Turk is the historian for the U.S. Marshals Service, the nation’s oldest federal law enforcement agency. Suggested for further reading: Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life, by Robert Utley; Alias Billy the Kid, by Don Cline; and History of the Lincoln County War, by Maurice Garland Fulton.

This article originally appeared in the February 2007 issue of Wild West magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.