By the afternoon of December 30, 1862, the cannoneers of Captain Warren P. Edgarton’s Battery E, 1st Ohio Artillery Regiment, were exhausted and worn down from hard marching and coping with adverse weather. Now, moving in column with their infantry support, Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson’s 2nd Division of Major General William S. Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland, the Buckeye gunners were on their way to cover the right flank of Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis’ division, advancing down the Franklin Road three miles or so west of Murfreesboro, Tennessee. As soon as Davis’ column came within range, Confederate artillery began to lay in spherical case shell among the Union infantrymen. The enfilade fire quickly drove the men of the division to lie flat on the ground, and Brig. Gen. Edward N. Kirk ordered Edgarton’s battery forward, supported by a regiment of infantry.

Covered by a cedar thicket, the gunners moved to within 700 yards of the Rebels, went into battery, and blasted out six rounds of solid shot. The shellfire forced the Confederate artillery to limber up and retire, leaving behind a wrecked caisson. Edgarton’s Ohioans then turned their attention to Confederate infantry coming up in support and kept up a brisk fire until dark.

The artillerists of Battery E were tired and famished after the action, and Kirk allowed them to go into bivouac amid a grove of cedars 100 yards behind their initial position. Edgarton complained to his brigadier that he could not properly place his guns in battery at that site. Kirk assuaged the young captain’s fears by replying that his cannons would be well-protected and that the Union infantrymen would provide sufficient time to limber up the guns and go into battery in the event it proved necessary.

Orders were circulated that no fires would be permitted that Tuesday evening, and Edgarton’s Ohioans bit down on flinty hardtack and drank cold and brackish water as they sullenly watched the brigade of Union Brig. Gen. August Willich form on their flank facing due south. The battery’s horses needed water, but in the darkness, with the enemy so near, the horses would have to wait until morning. Edgarton kept the horses in harness, hobbled near the guns and caissons.

Willich’s 1st Brigade lay on the extreme right of Maj. Gen. Alexander McD. McCook’s line, refusing the Federal right flank along the intersection of the Franklin Road and Gresham Lane. Willich issued orders for the 39th and 32nd Indiana to push forward a strong line of videttes without delay. At 3 a.m. Lt. Col. Fielder A. Jones, commanding the 39th Indiana, sent a company forward to probe the woods on the regiment’s front.

On Willich’s left, in a southwest-northeast line, the brigades of McCook’s 1st, 2nd and 3rd divisions fell in, anchored on their left by the Wilkinson Turnpike, a road that ran east of the Nashville Turnpike. Major General George H. Thomas’ center wing took up the Federal line, followed by Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden’s left wing, whose own left was secured by Stones River. Altogether, Rosecrans counted nearly 60,000 effectives.

Rosecrans’ nemesis, General Braxton Bragg, had taken up residence in middle Tennessee, south of Nashville, with the intention of providing his long-suffering troops with the opportunity to forage. Bragg had come under severe censure following his ill-fated invasion of Kentucky and the climax of the campaign, the Battle of Perryville, on October 8, 1862. The ignominious retreat of his army into Tennessee after that fight, as well as the paucity of forage and victuals, had inflicted incredible suffering on the Confederate rank and file. The emaciated ragamuffins marched out of Kentucky, a trek of more than 200 miles, subsisting only on parched corn and fouled water.

To make matters worse, Brig. Gen. Samuel Jones, commanding the district, failed to procure all the rations for Bragg’s army that Bragg expected to issue upon his arrival in the region. At the same time, the Confederate government unwisely permitted Robert E. Lee’s commissary general, Lucius Northrop, to purchase existing foodstuffs for the Army of Northern Virginia in the middle Tennessee region while Bragg’s command was fighting at Perryville. The final insult, delivered by an unsympathetic Mother Nature, was a 6-inch snowfall on November 1. Near starvation and now freezing, the Army of Tennessee began to disintegrate.

The unionists were in something of a quandary as well. On October 28, President Abraham Lincoln had replaced Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, commander of the Army of the Ohio, with Rosecrans. The new commander’s primary responsibility was to return the army to its nominal strength–nearly 7,000 soldiers had deserted since the bloodbath at Perryville–in order to prepare it for an advance into Tennessee.

Also troubling the Federal general were reports that Nashville, recently seized by Union troops, was about to fall. Rosecrans put his army’s three wings on the road for the Tennessee capital on November 4, with the van of the army arriving three days later. For the next two months, the opponents warily watched each other.

Once in Tennessee, Rosecrans began immediately to correct disciplinary problems within the army, improve morale and rejuvenate his cavalry. He also created a pioneer command of combat engineers whose specialized duties included constructing field fortifications, corduroying roads and building repair bridges. It was obvious that the Union army intended to stay in Tennessee for a long time.

By Christmas, Rosecrans had solved his most vexing problem, the lack of rations. A two-month supply was stored in Nashville warehouses. Meanwhile, he had received information that two of Bragg’s cavalry brigades, under redoubtable raiders Nathan Bedford Forrest and John Hunt Morgan, had been ordered west to assist other departments. With that threat removed, Rosecrans moved south at once to challenge Bragg.

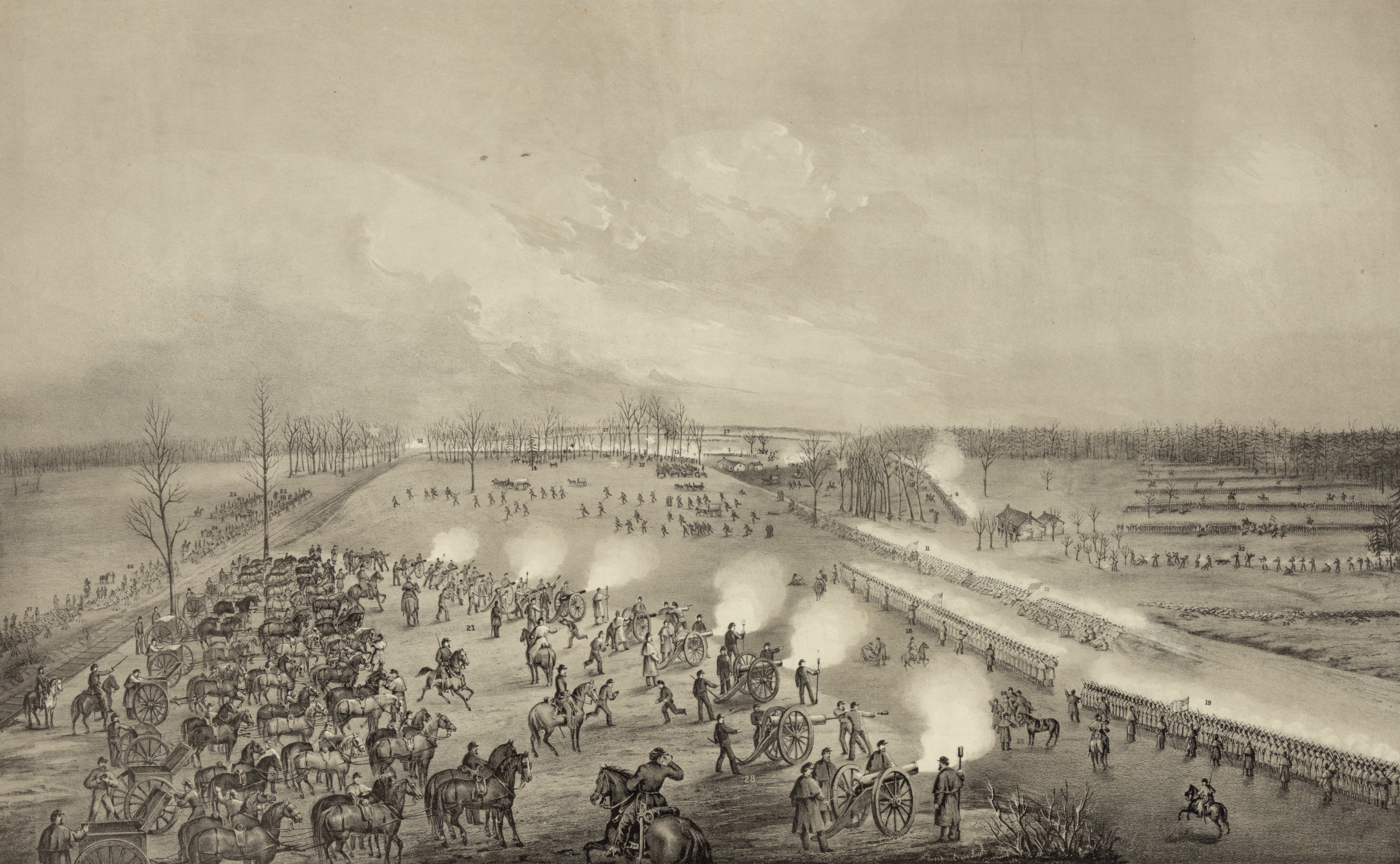

On the evening of Tuesday, December 30, Rosecrans and Bragg faced each other a few miles west of Murfreesboro. Bragg had waited all day Tuesday to receive a Federal attack that never materialized. Eager to seize the initiative, he took advantage of the Union lethargy to plan an assault of his own. After much discussion between Bragg and his corps commanders, Lt. Gens. Leonidas Polk and William J. Hardee, Polk suggested that his corps strike the right wing of McCook’s corps. Without debate Bragg assented; the assault would begin at dawn on Wednesday, December 31.

Unaware of these momentous Southern plans, Captain Edgarton kept busy prior to sunrise on December 31, finding a creek to the rear of his position and ordering half the battery’s horses taken back to the stream to be watered. Colonel William H. Gibson, commanding the 49th Ohio of Willich’s brigade, recalled later that ‘at dawn of day orders were received to build fires and make coffee. A little later the colonel ran into Willich, who was riding to his left to confer with his division commander, Johnson. Willich told Gibson to support the picket line in the unlikely event the Rebels advanced.

By early morning on the 31st, some 4,400 Confederates were ready to attack. Just after 6 a.m. the order to advance was quietly given, followed a few minutes later by the command to go double-quick. Five hundred yards in the rear, Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s division anxiously awaited the order to join the advance.

Kirk’s bluecoats saw them first. Moving swiftly, Maj. Gen. John McCown’s Confederate division piled out of the fog and mist, rushing toward the Union line. Colonel J.B. Dodge, who would eventually command the bri-gade after Kirk fell, reported that the Southerners came on formed in close columns, with a front equal to the length of a battalion in line and ten or twelve ranks in depth. The Union videttes managed to fire a single volley at the rumbling mass of graycoats, then fell back in panic, sounding the alarm.

Major Alexander P. Dysart’s 34th Illinois formed a double column in front of Edgarton’s artillery park on the right of Kirk’s brigade. When the firing started, Dysart quickly got his regiment moved into line, then went looking for Willich. Along the way he ran into Kirk, who ordered him to advance the 34th and give Edgarton’s Ohioans time to go into battery.

Dysart moved his regiment into an open field just as McCown’s Rebels broke through the cedar brakes to the east. The Union regiment immediately took a volley of musketry and smartly returned a fusillade of its own. Dismayed, the major saw more Rebels than he had ever seen before–five times as many men as he had himself. In a few short minutes nearly 70 of Dysart’s men were down, either dead or wounded.

The 34th got the order to retire on Edgarton’s battery. Dysart’s stalwart lads had no sooner reached the guns than they were swept away in the inexorable tide of fleeing soldiers, losing five color-bearers at the guns.

Southern bullets were now beginning to zip and hum into the clutch of men gathered about Edgarton’s battery. Kirk was shot down while attempting to rally his infantry. Although the tide was rolling against them, the Union troops gamely tried to slow the Confederate attack. Edgarton, Lieutenant Albert G. Ransom and their men managed to get one or two of their Parrot rifles into battery and fired shells and canister at the fast-closing enemy. Colonel J.C. Burks, commanding the 11th Texas Cavalry, fell disemboweled by the Union fire.

The Ohio artillerists made the dismounted Texans pay a heavy price for assaulting the battery, but the Lone Star soldiers succeeded in overrunning the gun crews, capturing Edgarton and a number of his men and horses. Several of the Ohioans were bayoneted in the fight for their guns.

On the left of the 34th Illinois, the 29th Indiana was responding promptly to the Confederate assault. Upon hearing the initial firing, Lt. Col. David M. Dunn ordered Lieutenant S.O. Gregory’s Company C forward in support of the picket line, and the unit soon found itself being enfiladed. After firing four or five volleys while lying in a prone position, the obstinate Hoosiers joined the dash to the rear.

On the left of the brigade line, the 77th Pennsylvania faced the assault of the 1st Arkansas Rifles, under the command of Brig. Gen. Evander McNair. The Federal pickets fell back on the regiment as the Pennsylvanians fought with desperate valor. The charge of the 1st Arkansas Rifles was broken, and the attackers were driven into a nearby cornfield, where the Union soldiers then found themselves without support and all but surrounded by Confederates. Without delay they fell back.

Kirk’s 2nd Brigade had suffered 826 casualties out of 1,933 effectives. More important, the brigade’s unity had been broken and individual soldiers scattered, running for their lives. In their flight southwest, they disrupted other Federal lines.

The 32nd and the 39th Indiana, posted on the Franklin Road, were hit simultaneously by McNair’s shock troops and Kirk’s fleeing men. Lieutenant Colonel Frank Erdelmeyer was unable to get his seven companies of the 32nd Indiana into line before they were swamped. Lieutenant Colonel F.A. Jones, commanding the 39th Indiana, managed to get Company A and part of Companies D and K into line behind a fence when the enemy opened a murderous fire. Almost half of Jones’ command fell dead or wounded under the first Confederate volley. They returned fire as best they could before Jones ordered a withdrawal.

The 49th Ohio was hit in flank and rear simultaneously by the 14th and 15th Texas Cavalry (dismounted). During the melee, Willich had been captured, and Colonel Gibson of the 49th Ohio assumed command of the brigade. Lieutenant Colonel Levi H. Drake then briefly led the 49th until he fell dead while cheering on his men. The Ohioans did not even have time to grab their stacked muskets before the wild-eyed Texans swept through their campsite.

The 10th and 11th Texas Cavalry (dismounted) and the 4th Arkansas drove into the 89th Illinois. Colonel M.F. Locke, commanding the 10th Texas, had suffered at the hands of Edgarton’s guns earlier; nearly 80 soldiers of the regiment had been knocked down in the assault. As Locke’s Texans closed upon the line of Illinois troops, pushing ahead of them the fugitives from Kirk’s brigade, Lt. Col. Charles Truman Hotchkiss, commanding the 89th, ordered his men to lie down. When the Texans came within 50 yards, Hotchkiss ordered his left wing to volley, and the Union musketry swept the line of the Texans.

Still the Rebels came on, overrunning the ranks of the last regiment to offer organized resistance, the 15th Ohio. The Ohioans joined the swarm of Federals sprinting for the rear. We stood to deliver our fire and say good morning, then took to our heels and ran, Private Robert Stewart recalled.

Inadvertently, the retreating Federals hurt the Rebel advance by sowing confusion among the attackers. While they were falling back, Cleburne’s usually well-oiled division was attempting to execute the right wheel movement that Bragg had ordered. But in the melee that followed the initial breakthrough, Cleburne’s complex maneuver became unhinged. His left brigade, under Brig. Gen. St. John Liddell, found itself running to perform the movement, while the center brigade, led by Brig. Gen. Bushrod Johnson, marched at a measured parade-ground stride. On the right, Brig. Gen. Lucius Polk’s command was becoming dangerously exposed as it moved to keep up with the other brigades. Hardee solved Polk’s dilemma by bringing up Brig. Gen. S.A.M. Wood’s brigade to fill the gap.

General Davis, hearing the firing on his right, ordered back Colonel Sidney Post’s 1st Brigade, in effect refusing the division’s right flank. Post’s amalgamated force of three Illinois regiments and one Indiana regiment fell in along a lane, with the 74th and 75th Illinois, both novice regiments, posted behind a split-rail fence on the east side of the road. The two remaining regiments, the 59th Illinois and 22nd Indiana, formed on the west side of the lane, with Captain Oscar Pinney’s 5th Wisconsin Battery dropping trail in a cornfield between the two regiments. Pinney’s well-maintained Parrott rifles had the benefit of a half-mile-deep field of fire, and his gunners worked swiftly to go into battery.

Load solid shot, fire by section, on my command! Pinney shouted as he cast his gaze along the line of eager Confederate infantrymen 1,000 yards to his front. Section One, Fire! came Pinney’s command, and the roar of 12-pounder Parrott rifles thundered across the glen. Section Two, Fire! Section Three, Fire!

Pinney’s fire found the mark. The 17th Tennessee, commanded by Colonel A.S. Marks, had advanced in fine style before halting 150 yards in front of the Federals and firing a volley. In the ensuing artillery fire, Marks fell severely wounded, and command devolved upon Lt. Col. Watt Floyd. At the same time, Colonel John M. Hughes, commanding the 35th Tennessee, took a serious head wound and was carried to the rear. His replacement, Lt. Col. Samuel Davis, observed later that I never saw in any battle a more regular and constant fire.

Captain Hendrick E. Paine, commanding the 59th Illinois, which was posted west of Pinney’s guns, ordered his men to fire, and lie down and load. Bushrod Johnson, seeing the damage being inflicted on his Confederates, sent a message to Captain Putnam Darden of the Jefferson Flying Artillery to bring up his guns. I immediately moved by the left flank, Darden reported, to an elevated position, and came into battery to the right under a murderous fire of canister, from one of the enemy’s batteries, posted about 400 yards distant.

Both Union and Confederate brigades became locked in battle. Sam Davis of the 25th Tennessee reported, Although a great many of our men were killed and wounded at this place, the line was not confused, and the men continued to fire without noticing those killed or wounded. Paine commented, I do not know how long we remained in that position, but my men poured a deadly and destructive fire upon the enemy.

Bushrod Johnson’s Tennessee regiments paid special attention to Pinney’s Parrott guns, and men and horses began to fall to the Southern musketry. For 30 minutes, the forces fired on one another at a distance of 75 yards. Casualties began to rise. Pinney fell beside his guns–he and many of his cohorts would be left on the field. Post ordered the guns limbered up and withdrawn, but 18 of the battery horses were down, leaving two badly shot-up beasts to pull one of the Parrott rifles. The men of the 59th Illinois ran to the guns, tied ropes to them and began to pull them out of the fray. They got off five of the guns under a deadly fire.

Four hundred yards northwest of Post’s position, Colonel Philemon Baldwin, commanding the 3rd Bri-gade of Richard Johnson’s 2nd Division, had no sooner prepared for the Confederate assault than the enemy, in immense masses, appeared in my front at short range, their left extending far beyond the extreme right of my line. Baldwin’s regiments took up a truncated line, with the 6th Indiana and 1st Ohio making up the front and a section of guns from the 5th Indiana placed in advance. Two additional sections went into battery in a cornfield to the rear of the Ohioans. The 5th Kentucky (Union) formed the second line, with the 93rd Ohio acting as brigade reserve.

Major Joab A. Stafford, commanding the 1st Ohio, reported that at a range of 150 yards he opened fire on the Confederates. First Lieutenant Henry Rankin, commanding the two 12-pounders to the left of the 1st Ohio, opened with canister on the butternut columns, while the two other sections of Captain Peter Simonson’s 5th Indiana Battery opened with case shell.

Facing the ferocious Federal gunfire, the attacking Southerners threw themselves down in order to avoid the deadly blasts. Battle smoke swirled about the cornfields, obscuring the ranks of both sides. Remnants of Willich’s and Kirk’s brigades, broken and dispirited, halted long enough to show the flag, fire a volley, then run again, with the Confederates in battle-crazed pursuit.

The Union infantry along Baldwin’s line began to break for the rear. Simonson, however, switched his battery to canister, obliqued his Parrott rifles, lowered his barrels to zero degrees and fired. Several dismounted Rebel cavalrymen were killed or wounded. A retaliatory volley from the Arkansans, however, put down 24 of the Union cannoneers killed or wounded. With great difficulty and valor, the shredded remnants of the 5th Indiana Battery managed to drag off all but two of their pieces with the help of some infantrymen.

To the right of Baldwin’s collapsing line, the Confederate brigades of Wood and Polk plowed into the cedar brakes, confident that their way was unobstructed. Within minutes both units had been bushwhacked. Union regiments of Colonel William Carlin’s 2nd Brigade caught the unsuspecting Rebels in motion and volleyed into their massed lines. In just another of the day’s hurried maneuvers, Polk right wheeled his bri-gade, called up one 12-pounder from the Helena Battery, and enfiladed Carlin’s line.

Carlin tried to withdraw his brigade in an orderly manner, but both he and his mount were hit by rifle fire and knocked down. Colonel Hans Heg, commanding the 15th Wisconsin, maneuvered his regiment where it could best cover the retreat of the remaining troops and slowed down the Confederate advance long enough to get out the infantry and the brigade’s artillery. The hard-fighting 15th Wisconsin was the last out to safety.

By now, two of McCook’s Union divisions had been broken and scattered. Only one officer stood to stem the Confederate tide: the irascible, bandy-legged Ohioan, Brig. Gen. Phil Sheridan.

Unlike the two Federal divisions farther south, Sheridan had his soldiers alert and ready prior to the dawn attack. At this time the enemy, who had made an attack on the extreme right of our wing against Johnson and also on Davis’ front, had been successful, and the two divisions on my right were retiring in great confusion, he reported. Sheridan’s 3rd Division made a valorous stand along the Wilkinson Pike, slowing down the Confederate attack long enough for Rosecrans to cobble together a second line.

The following day, January 1, 1863, both sides paused to catch their breath and regain some of their strength, and no major fighting took place. On the 2nd, though, the tempestuous battle resumed when Bragg commanded Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge’s division to assail the Union left. Massed Union artillery smashed this effort, and it was the Confederates’ turn to fall back in gory confusion. Bragg retreated from the area on January 3, and Rosecrans claimed victory–an unlikely outcome considering the catastrophe his forces had suffered on December 31. Overall, both sides lost more than 18,700 killed or wounded in the midwinter battle.

For the unfortunate Captain Edgarton and his gunners, Stones River held no moments of glory. Captured, discredited and dishonored, Edgarton would be exchanged a few months later and then be called upon to report why he had sent half his horses to be watered on the morning of the fateful assault. Laying much of the responsibility for the battery’s terrible location on his slain brigadier, Edward Kirk, Edgarton requested, As I have been charged with grave errors on the occasion of the battle, I respectfully request that I may be ordered before a court of inquiry, that my conduct may be investigated.

Such an investigation was never completed, but a note was made of Edgarton’s performance at Stones River and placed in the official records: Edgarton, captain…Company E, 1st Ohio Artillery…was guilty of a grave error in taking even a part of his battery horses to water at an unseasonable hour, and thereby losing his guns. Edgarton’s military career was over, but at least he had his life–unlike many soldiers who were there during the rout of the Union right that cold December morning in 1862.

This article was written by Robert Cheeks and originally appeared in the September 1999 issue of America’s Civil War magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!

More Battle of Stones River Articles

Stones River: Philip Sheridan’s rise to military fame Brigadier General Philip H. Sheridan sat pensively in his command tent the evening of January 9, 1863, and stared at the paper on his camp desk. ‘At 2 o’clock on the morning of the 31st [December 1862] General Sill, who had command of my right brigade,’ he began. Words eluded him as he set aside his post-action combat report and mused for a moment, remembering an old friend, now dead. His face flushed red, and his thoughts went back to the day before the New Year, the day of the Battle of Stones River, the day he wrecked his division to save the army.

Read the rest of the Stone River Battle Article

Battle of Stones River: Union General Rosecrans Versus Confederate General Bragg Steadily the rain had pelted down all day, and now as wintry winds and darkness ushered in another miserable night at the mercy of the elements, the battle-tried veterans of Perryville, both Blue and Gray, struggled to find what fitful sleep they could. The following morning, the last one of 1862, would certainly be the last for many of them. In just a few hours, the fields and cedar thickets around the Tennessee village of Murfreesboro would shake with the angry roar of cannons and the sharp crackle of musketry

Read the rest of the Stone River Battle Article