The Battle of Fort Sumter was the first battle of the American Civil War. The intense Confederate artillery bombardment of Major Robert Anderson’s small Union garrison in the unfinished fort in the harbor at Charleston, South Carolina, had been preceded by months of siege-like conditions.

Facts

Where was the battle of fort sumter?

The battle took place at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina.

when was the battle of fort sumter?

The battle took place on April 12 and 13, 1861.

Generals

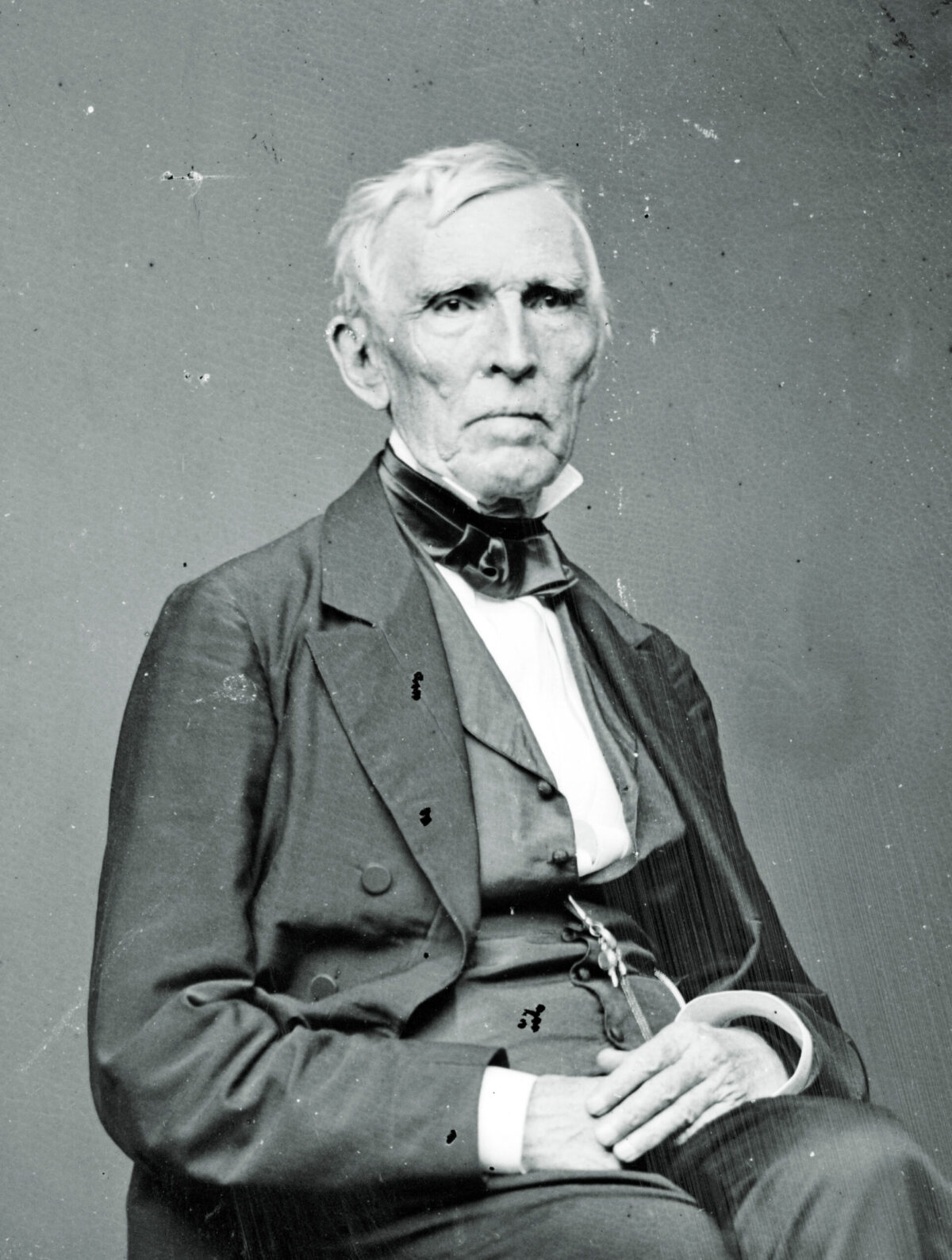

- Union: Major Robert Anderson

- Confederate: Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard

Soldiers Engaged

- Union: 80

- Confederate: 500

Important Events & Figures

- Edmund Ruffin

- Abner Doubleday

- Louis WIgfall

- Private Daniel Hough

- Private Edward Galloway

Who Won the Battle of Fort Sumter?

It was a Confederate victory.

Fort Sumter Casualties

- Union: 0

- Confederate: 0

Related Stories & Content

What Happened at the Battle of Fort Sumter?

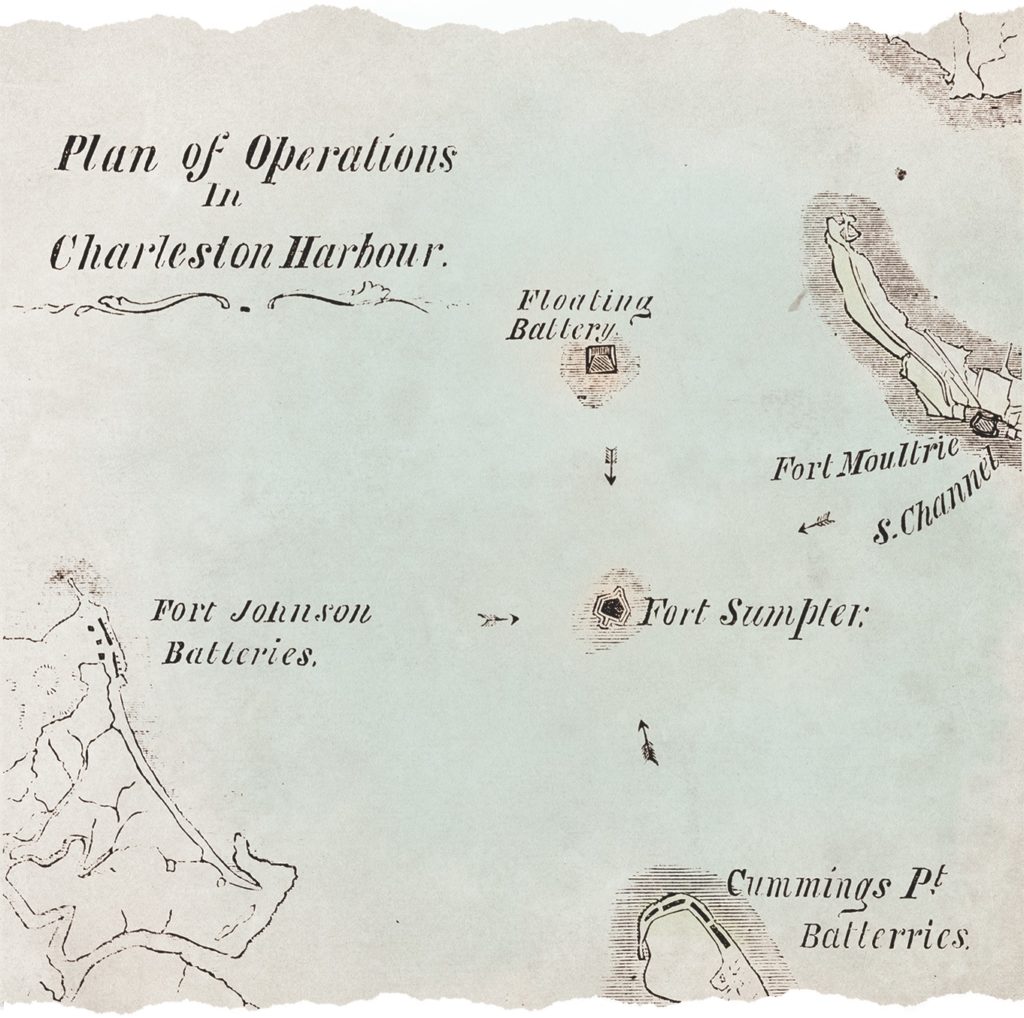

During the secession crisis that followed President Abraham Lincoln’s election in November 1860, many threats were made to Federal troops occupying forts in the South. Anderson, in command at the difficult-to-defend Fort Moultrie on Sullivan Island across the harbor from Charleston, began asking the War Department for reinforcements and making plans to move his men to one of the fortifications on more secure islands in the harbor—Castle Pinckney closer to Charleston or the unfinished Fort Sumter near the harbor’s entrance.

Following South Carolina’s secession on December 20, 1860, Governor Francis Pickens was pressured to do something about Anderson and his men since many believed that Anderson would not stay at Fort Moultrie but would take a better position at another of the harbor’s forts. On December 24, Pickens sent proxies to Washington to negotiate what would be done about the occupied forts and to ensure Anderson remained at Fort Moultrie. However, on December 26 Anderson put his plan into action: he assembled his men, loaded them and their families onto boats, and rowed to Fort Sumter. What followed was basically a siege of Fort Sumter, with supplies and communication controlled by Pickens.

On January 9, 1861, the Star of the West, a side-wheel merchant steamer that had been sent from New York with supplies and reinforcements for Anderson, was unable to reach Fort Sumter because Pickens had built up the harbor defenses and fired on it. Anderson, under orders to fire only in defense, could only watch as the ship was turned back.

Shortly after, on January 11, Pickens demanded surrender and Anderson refused. By January 20, the food shortage had become acute enough that Pickens was under criticism from moderates and sent food to the fort, which was refused by Anderson. Shortly after, Pickens allowed the evacuation of 45 women and children to provide some measure of relief.

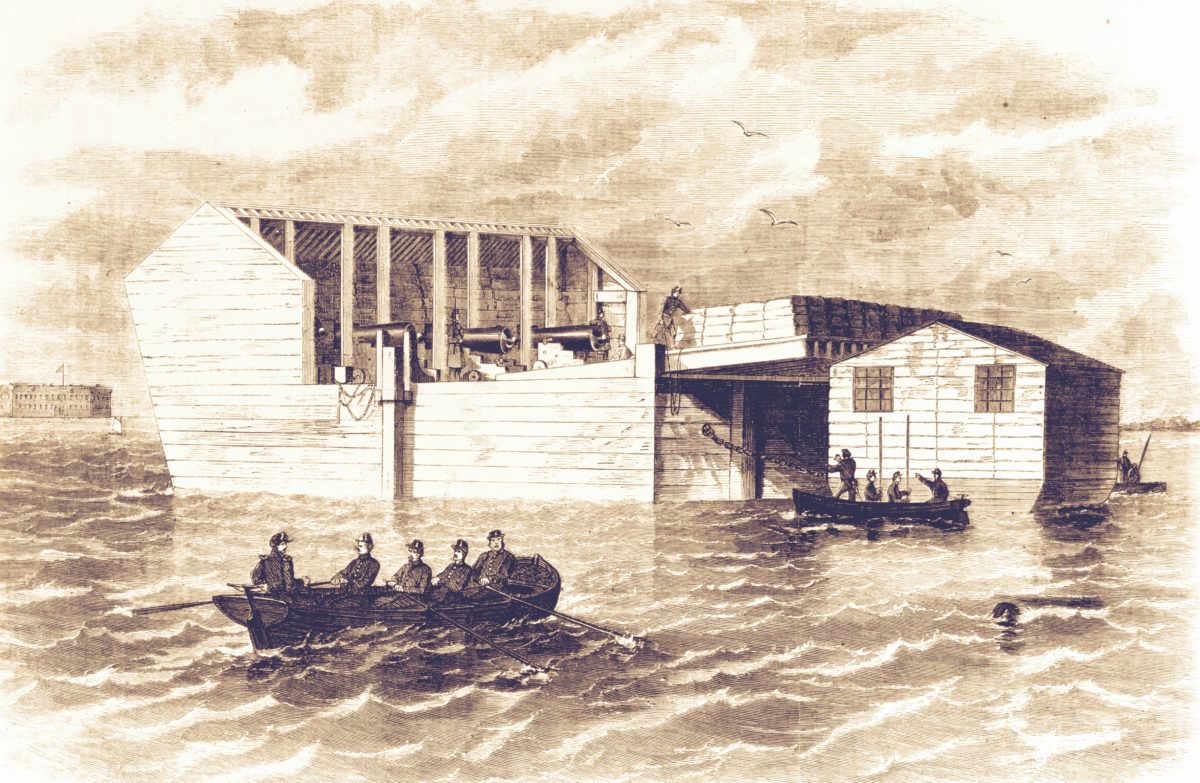

On March 1, Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard arrived in Charleston. He had been appointed by Confederate president Jefferson Davis to take command of the military situation in Charleston. In the sort of twist of fate that would happen frequently during the war, Beauregard had been one of Anderson’s artillery students at West Point. Beauregard continued strengthening the harbor defenses and gun emplacements facing Fort Sumter.

Following his inauguration on March 4, 1861, Lincoln sent unofficial emissaries to observe the situation and report back to him while official negotiations with the Confederate government took place in Washington. He learned that Anderson would probably be out of food by mid-April. Anderson had indicated he needed supplies and reinforcements in early March and again on April 3, but did not received news or further instruction until April 8, when he received a letter from Washington informing him of that a relief expedition was being mounted. The Lincoln administration left the question of war up to the Confederates, which would be determined by whether or not they fired on the Federal supply ship and the fort, which the Federals did not intend to give up.

As news of the relief expedition percolated through the Confederate government, Beauregard was instructed to demand the fort’s surrender and fire on it if surrender was refused. Beauregard began moving men and artillery into place and on April 11 and sent envoys to Fort Sumter to demand surrender. Anderson, after polling his men, once again refused. Following the refusal, Beauregard was asked to assess how long it would be before Anderson would run out of food and be forced to surrender, so just after midnight on April 12, the envoys arrived back at the Fort. Hoping the relief expedition would arrive before then, Anderson said he would surrender at noon on April 15. He was informed that was not soon enough, firing would began at 4:30 a.m.

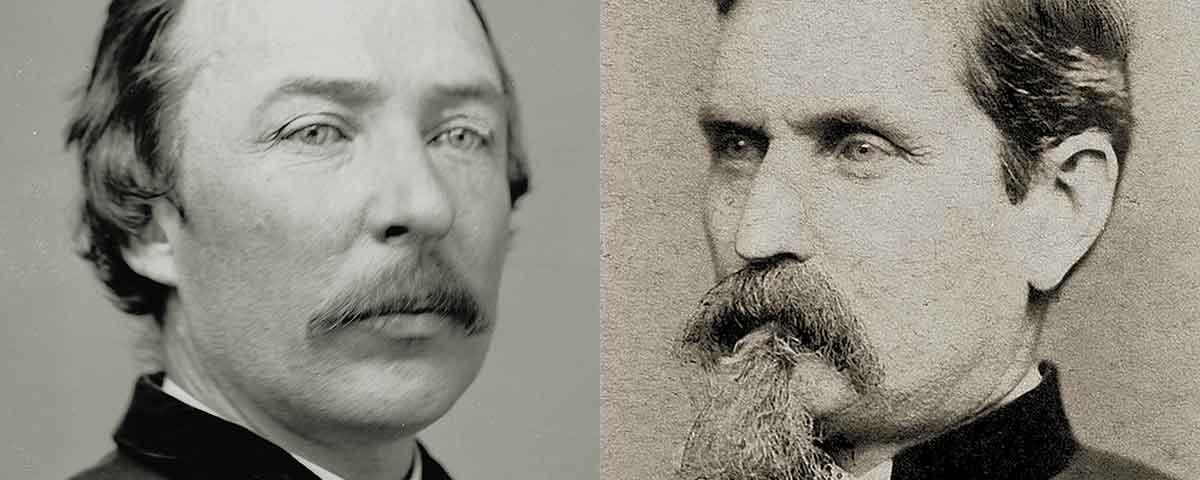

After a signal gun was fired, Virginia fire-eater Edmund Ruffin, who had campaigned relentlessly through the 1850s for states’ rights, slavery, and secession, was given the honor of firing the first shot at Fort Sumter. Anderson, to reduce his casualties and conserve ammunition, did not return fire until just before 7:00 a.m. when Captain Abner Doubleday fired the first return shot. Anderson also tried to reduce casualties by only using the guns from his lower casemates, where his men would be less exposed. Later in the morning, the barracks caught fire and many of his men had to be used as a fire crew. In the afternoon, they spotted the three ships flying the US flag just outside the harbor and thought they would be resupplied during the night, not realizing that the ships were actually on their way to Fort Pickens in Pensacola, Florida.

As night fell, Anderson stopped firing and the Confederates reduced their fire but resumed it the next morning. April 13, the barracks again caught fire and threatened the ammunition store, in spite of the rainy day. At about 1 p.m. the flagstaff was shot away and the flag was raised on the ramparts on a makeshift staff. On seeing the flag shot away, Louis Wigfall—aide to Beauregard, fire-eater, and former U.S. senator—rowed out to Fort Sumter on his own initiative, without the knowledge or approval of Beauregard, amid the continuing barrage to see if Anderson was attempting to surrender. Although initially told that Anderson was not surrendering, Wigfall was able to negotiate a surrender. At 1:30 p.m., the flag was replaced with a white sheet. On seeing the flag of surrender, Beauregard ceased firing and sent his envoys to the fort, where they learned of Wigfall’s unofficial mission. After further negotiation, the same terms were eventually agreed to: surrender would occur April 14 at noon.

The people of Charleston came out in boats on April 14 to watch the surrender and evacuation. As part of the surrender terms, Anderson had received permission to fire a 100-gun salute while lowering the American flag before departing. Halfway through, one of the guns discharged prematurely, killing Private Daniel Hough, who had emigrated to the U.S. from Ireland in 1849, and mortally wounding Private Edward Galloway. Reportedly, Hough was buried at the fort, but that has not been proven. The rest of the men were taken by boat to the relief ships just outside the harbor. On April 15, 1861, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the Southern rebellion. The Civil War had begun.