Union Sergeant Frank Donaldson of the 1st California struggled to help a wounded friend into a boat returning to Harrison’s Island, then turned to make his way back to the fight raging at the top of the 70-foot-high Ball’s Bluff. A man whose lower jaw had been shot away was in his path, but Donaldson had to ignore him; his mission was to help serve a mountain howitzer, not to render aid. Upon reaching the summit, he began to gather rocks that could be fired out of the cannon, as all the ordnance that had been brought over had been expended. During periodic lulls in the firing, he could hear the incongruous sound of a band on the island playing military airs.

Donaldson’s regiment was part of a 1,700-man force fighting an unintended and unplanned battle near Leesburg, Va. That day, October 21, 1861, was one that Donaldson would not likely soon forget.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff was a Union debacle that occurred during a period of quiet in the eastern theater, ensuring it a great deal of publicity. Southerners celebrated it as a follow-up thrashing to First Manassas, while Northerners bemoaned yet another defeat in northern Virginia. As such, the little fight would have major implications, particularly for the Union.

Despite traditional historical interpretations, the engagement was not the result of a preplanned Federal attempt to take Leesburg. It was rather an accident that evolved out of the carelessness of an inexperienced infantry officer who reported seeing something that was not there.

Captain Chase Philbrick’s Company H, 15th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, was picketing Harrison’s Island, an island 2 miles long and 300-400 yards wide that bisects the Potomac River at Ball’s Bluff. The bluff itself, some 35 miles northwest of Washington, D.C., runs for about 600 yards along the Virginia shore, rising steeply from the 50-yard-wide flood plain that separates it from the river.

On October 20, Philbrick’s commander, Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, whose Maryland-based division was rather grandly known as the Corps of Observation, began moving troops around to give the impression that he was about to cross in force in response to an order from Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George McClellan that he should conduct ‘a slight demonstration’ to see what effect it might have on the enemy.

McClellan’s belief that the Confederates might have abandoned Leesburg spawned that order, and on October 16-17, the Rebels had indeed left the town. Regional Confederate commander Colonel Nathan G. ‘Shanks’ Evans had been keeping a wary eye on the growing Federal forces across the river. The threat seemed to grow on October 9, when Union Brig. Gen. George McCall crossed his 12,000-man division at Chain Bridge and established a camp at Langley, Va., 25 miles east of Leesburg.

A week earlier, on October 3, Colonel Edward D. Baker’s large ‘California Brigade’ reinforced General Stone’s division, bringing the Union numbers to something over 10,000 men near Ball’s Bluff. Baker and his brigade were a story unto themselves. The four regiments were made up mostly of Pennsylvania men, but had been tagged the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 5th California because Baker had long been affiliated with California and wanted it formally represented in the Eastern army. Baker was, in fact, a senator from Oregon and a close friend of Abraham Lincoln from the prewar political arena. So close were the two that the president had named his second son Edward Baker Lincoln.

Evans interpreted McCall’s and Baker’s movements to mean an imminent advance on Leesburg. The town was strategically located on the Confederacy’s Potomac River frontier due to several militarily usable fords across the river and two working ferry sites. Whoever controlled the river there controlled invasion routes into Virginia. Several fortifications had been built to protect the area, including Fort Evans along the Edwards Ferry road, some three miles south of Leesburg. Evans, quite reasonably, became concerned that he did not have enough men. His brigade numbered only 2,500 to 2,800 men, and the closest supporting troops were 25 to 30 miles away along the Bull Run line.

On the evening of October 16, on his own authority, Evans began shifting his brigade south along what is more or less today’s U.S. Route 15. That night and all the next day, he moved to establish a new defensive line some eight miles south of Leesburg behind Goose Creek.

His commander, General P.G.T. Beauregard, was displeased by the move and indicated his displeasure through a sarcastic third-party message that said Beauregard ‘wishes to be informed of the reasons that influenced you to take up your present position, as you omit to inform him.’ Evans took the hint, and by late on October 19, his brigade returned to the town.

Federals observed Evans’ southward movement and reported it to McClellan, who ordered McCall to investigate by taking his division on a reconnaissance-in-force as far west as Dranesville, about halfway between Langley and Leesburg. McCall did so on October 19. By that evening each side must have been very puzzled about the other’s intentions.

General McClellan suspected a trap, thinking that Evans might be attempting to draw some of his forces forward in order to cut off and destroy them. When Evans learned that McCall was in Dranesville, he may well have thought that he had brought on the very advance that he earlier had feared.

On the morning of October 20, McCall was probing westward toward Leesburg. Evans was along another portion of Goose Creek four miles east of Leesburg and some eight or nine miles from McCall. McClellan then ordered Stone to conduct the’slight demonstration’ that led to Captain Philbrick’s involvement.

By the evening of October 20, Stone’s demonstration was over and the Federal regiments were on their way back to their camps. In order to determine the effectiveness of the movement, he ordered Colonel Charles Devens to send a patrol across the river at Ball’s Bluff. Philbrick got the assignment partly because his company was already on Harrison’s Island and partly because he had led a similar patrol on the evening of October 18 that had familiarized him with the area.

Around dusk, Philbrick and a handful of volunteers using two small skiffs quietly crossed to Ball’s Bluff. The patrol moved downriver along the flood plain at the base of the bluff, then up a winding path that came out just behind the current national cemetery. Philbrick’s men cautiously advanced away from the river along a cart path some 10 or 12 feet wide. They crossed a large clearing and passed through some woods to open fields. A full moon had bloomed on October 18, and still provided some uncertain light.

Lieutenant Church Howe later described the patrol: ‘We proceeded…three quarters of a mile or a mile from the edge of the river. We saw what we supposed to be an encampment. [There was] a row of maple trees; and there was a light on the opposite hill which shone through the trees and gave it the appearance of the camp.’Captain Philbrick took the patrol back across the river and reported the presence of ‘a small camp without pickets.’ General Stone called the discovery ‘a very nice little military chance.’ He decided to raid the camp, and the chain of errors that led to the Union debacle had begun. Captain Philbrick’s inaccurate, faulty report would lead to the Battle of Ball’s Bluff.

Preparations were made throughout the night and into the early hours of October 21 for a raid limited solely to the supposed camp. Indeed, General Stone specifically ordered Colonel Devens to make his raid ‘and return to his present position.’

A second crossing was also planned downriver at Edwards Ferry. Stone ordered Major John Mix, an old Regular Army man commanding a battalion of the 3rd New York Cavalry, to take 30 to 35 men across the river and move out the Edwards Ferry road toward Leesburg. Mix’s assignment was to draw Confederate attention away from Devens so that he would be able to conduct his raid and get safely back. Mix also was to scout the roads between the river and the main highway into Leesburg from the east (today’s Route 7 East, the road down which General McCall would march should he be ordered to move on the town). Having done those things, Mix was to recross the river. Believing that he would be back in Maryland by 8:30 or 9 a.m., he ordered the regimental cooks to have breakfast ready.

As things developed, Shanks Evans, also aware that McCall was only a few miles away in Dranesville, believed the Yankees were planning an envelopment of the town, but McCall had neither plans nor orders to advance on Leesburg. McClellan actually ordered him to return to Langley on October 20, but McCall needed an extra day to complete his reconnaissance survey of the roads. So quite by coincidence, McCall’s orders called for him to withdraw from the area just as the fighting at Ball’s Bluff was getting started.

Colonel Devens shuttled his raiding party, 300 men from the 15th Massachusetts, across the river in the patrol’s two skiffs and a slightly larger ‘Francis metallic lifeboat’ that held about 15 men and was dragged across the island for their use. Some 30 to 35 men at a time could make the crossing in the three boats. Just over 100 troops from the 20th Massachusetts followed the 15th Massachusetts men. Their job was to deploy on the bluff, cover the withdrawal of Devens’ men following the raid, and then recross to the island under cover of fire from infantry and two mountain howitzers stationed there.

Getting more than 400 men across the river in three small boats, in the dark and as quietly as possible, was a touchy assignment made more so by the fact that heavy rains during the previous three weeks had caused the river to rise well above normal. The shuttling of troops to the Virginia shore took most of the night.

Colonel Devens consulted with Colonel William R. Lee, who commanded the 20th Massachusetts and accompanied his 100 men to the bluff. Devens then ordered his men to the attack as soon as it was light enough to see. Sunrise that morning came at 6:26, so it may be presumed that he moved out at about 6.

Devens soon discovered that his raiding party had nothing to raid. Had he decided to return to the island at that point, the story would have ended there. General Stone, however, had given him the discretionary authority not to return immediately should he either drive the enemy easily or find that the situation was quiet and there was no threat. Colonel Devens decided to stay.

He sent Lieutenant Howe back to tell General Stone about the mistake and to request further instructions. Howe returned to the river, crossed over and rode to Edwards Ferry, reporting to Stone around 8. On hearing Howe’s report, Stone decided to turn the raid back into a reconnaissance and ordered the remainder of the 15th Massachusetts to join Devens. The force then was to advance toward Leesburg to gauge the enemy’s strength in the area. Howe went ahead of the reinforcements and told his commander of the new orders.

Howe’s message to Stone, however, was irrelevant before it was delivered. Devens actually was making contact with the Confederates as Howe was talking to Stone. Pickets from Captain William Duff’s Company K, 17th Mississippi Infantry, had briefly engaged a small patrol from the 20th Massachusetts near Smart’s Mill, a mile or so north of Ball’s Bluff. About four men on each side exchanged shots, then withdrew. First Sergeant William Riddle of the 20th Massachusetts was severely wounded in the elbow, the battle’s first casualty.

The Mississippians sent word to Colonel Evans that Union troops were across the river, but no one from the 20th Massachusetts bothered to inform Colonel Devens of the contact. He therefore was surprised when his scouts reported Confederate troops moving toward his position.

Captain Duff gathered his 40-45 men and moved southward in order to get between the enemy and Leesburg. He encountered Devens’ men near the home of Mrs. Margaret Jackson, a little north of where the camp mistakenly was reported to have been and several hundred yards from the bluff. Devens had 300 men with him, but, not knowing that he faced so few Confederates, he held most of his men in reserve and sent only Captain Philbrick’s 65-man Company H forward to meet Duff, triggering a 15-minute firefight at about 8 a.m. The Southerners got the best of it, as they killed one, wounded nine and captured three of the Federals while suffering only three minor wounds themselves. Both companies withdrew, and there was a lull of about three hours while both sides fed reinforcements into the area.

The balance of Devens’ 15th Massachusetts were the first Federals to arrive, and the initial Confederate reinforcements were troopers from several companies of the 4th and 6th Virginia Cavalry led by Lt. Col. Walter Jenifer. Jenifer had heard the firing, pulled together as many horsemen as he could, and ridden to the sound of the guns. Both sets of reinforcements arrived after the initial skirmish had ended.

Shortly after Howe left General Stone, Colonel Edward Baker had arrived at Edwards Ferry to find out what was going on. Neither he nor his brigade had played any part in the demonstration, the patrol or the raid, but Stone had ordered Baker to bring his men to Conrad’s Ferry, just above Harrison’s Island, in case they were needed.Relying on Howe’s outdated information, Stone gave Baker command of all Union forces around Ball’s Bluff, permitting him to order across additional troops or recall those already in Virginia, depending on his evaluation of the situation. Neither Stone nor Baker knew that fighting already had broken out. Both were thinking only of an expanded reconnaissance.

On his way back upriver between 9:30 and 10, Baker ran into Lieutenant Howe, now returning to Edwards Ferry with the new information about the Duff-Philbrick skirmish. Baker thus learned of the fighting before Stone did and said, according to Howe, ‘I am going over immediately, with my whole force, to take command.’ Instead of doing that, however, he began throwing as many troops across the river as he could while spending most of the next four hours directing a search for more boats. Baker not only failed to go the battlefield, he also neglected to put anyone in charge on the Virginia side. Nor did he give any orders to the men already there. Each unit that crossed was effectively on its own.

As additional troops arrived, two more skirmishes erupted near the Jackson house. One occurred around 11:30 between the roughly 650 men of the 15th Massachusetts and a mixed force of Mississippi infantry and Virginia cavalry of about the same size. At almost every point of contact during the day, the opposing forces were fairly evenly matched, though each side reported being heavily outnumbered by the other.

A third skirmish took place around 1 p.m., after the 8th Virginia (minus one company) arrived with just under 400 men. Though larger than the previous skirmishes, it also was indecisive and was followed by a lull. By about 2, Colonel Devens, whose men had done all the fighting on the Union side thus far, decided to withdraw to the bluff, where he knew that he would have some help.

Coincidentally, Baker finally had crossed to Ball’s Bluff and met Devens there at about 2:15. He approved of Devens’ withdrawal and ordered him to take a position on the right of, and perpendicular to, the Federal line. The position, sometimes called a chevron formation, would have looked from the bluff like a backward ‘L.’ In one wing, facing west or inland, the men of the 20th had their backs to the bluff. The other wing, the 15th Massachusetts, faced south. Together they faced an open field and covered the cart path on which any troops coming into the clearing would have to march, forcing them into a crossfire. To beef up the defense, the 20th had dragged two mountain howitzers up the slope and added them to the line. A short while later, a James rifle fieldpiece was also brought up the bluff.

Baker sent two companies of his 1st California Infantry up the slope on his left front. He thought that as many as 7,000 Confederates might be there (it actually was closer to 700), but he wanted to be sure. That move resulted in those two companies meeting a portion of the 8th Virginia around 3 p.m., marking the beginning of almost continuous fighting that lasted until after dark.

Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Wistar of the 1st California claimed the Virginians ‘rose up from the ground’ to blast his men, who took heavy losses and fell back. Confusion within the 8th Virginia, however, caused a good portion of the regiment to break and run. Colonel Eppa Hunton apparently ordered the 8th to withdraw to a better position a short distance to the rear about the same time that the clash occurred. That order and the shock of the clash seem to have combined to create a panic in the regiment’s rightward-most companies. Hunton reacted by moving the unit to the left and rear, where he spent nearly two hours reorganizing his men and getting them back into the fight.

As Hunton was moving to his left, Colonel Erasmus Burt moved his 18th Mississippi into their former place. After the men were situated, Burt almost immediately ordered them forward. Not seeing the right wing of the Federal chevron because those men were under the cover of woods and sloping ground, Burt marched directly into what Rebel cavalryman Elijah White, a local resident home on furlough and acting as a guide, later called ‘the best directed & most destructive single volley I saw during the war.’ More than half of the 18th Mississippi’s 85 casualties that day came from that volley. Burt was one of them. Shot through the hip, he was taken into Leesburg, where he died five days later.

The Mississippians pulled back and were split into two battalions by Lt. Col. Thomas Griffin. One moved to the left and the other to the right, creating an opening of some 200 yards in the Confederate line. The Federals did not exploit that gap, and it eventually would be filled by the 17th Mississippi. As the afternoon developed, the Rebels constructed a U-shaped line that penned the Union troops in along the precipitous bluff.

Mixed companies of the 18th and 17th Mississippi Infantry anchored the left flank, with the reorganized 8th Virginia next in line. The rest of the 17th Mississippi then filled in the aforementioned gap between 4:15 and 5 p.m., and seven companies of the 18th Mississippi held down the right flank of the gray line. Company H of the 18th was on the extreme right, separated from its comrades by a ravine.

The Union troops were even less organized than their foe, as various companies and battalions of the 15th and 20th Massachusetts, the 1st California and the 42nd New York were moved to threatened areas. Other elements of the 42nd New York were the final piece in the Union puzzle, crossing over later in the day and taking an initial position roughly in the Federal center.

After Burt’s mortal wounding, the fighting was almost continuous, becoming a swirl of individual company or battalion actions. One Yankee called it a fight ‘made up of charges.’

The 18th Mississippi kept working around the Confederate right, assaulting out of a ravine at least five times. Each time they were repulsed. The Union cannons, though in the open, contributed to holding the line. When the vulnerable artillerymen were quickly shot down, infantrymen came forward to man the guns.

It was probably during the final assault by the 18th Mississippi on the Union left, between 4:30 and 5, that Colonel Baker was killed. Many descriptions have been left of Baker’s death, though one of the most credible came from Captain Caspar Crowninshield of the 20th Massachusetts, who reported seeing Baker rallying his men when he was shot, ‘got up again and then fell, struck by eight balls….’ Hand-to-hand fighting occurred before Union troops could retrieve Baker’s body. The colonel remains the only U.S. senator ever killed in battle.

Colonel Milton Cogswell of the 42nd New York eventually took command of the Union forces and attempted to break through the Confederate right flank. Had that been tried earlier, it might well have succeeded. But by the time the beleaguered Yanks made their charge, it was a desperate move that fell apart almost before it began.

The fight continued to rage as the Federals made other failed attempts to drive away their Rebel tormentors. Things came to a head when the 17th Mississippi, about 700 fresh troops with full cartridge boxes, and supported by much of the 18th and possibly a company of the 13th Mississippi, advanced on the worn-out Federals.After filing into the gap in the Rebel line, the 17th’s commander, Colonel Winfield Scott Featherston, had his men lie down. ‘No lizards ever got closer to the ground than we did,’ remembered one Mississippian. The men soon rose again at Featherston’s command and moved forward in the final attack that drew in troops from the other Rebel regiments around dusk.

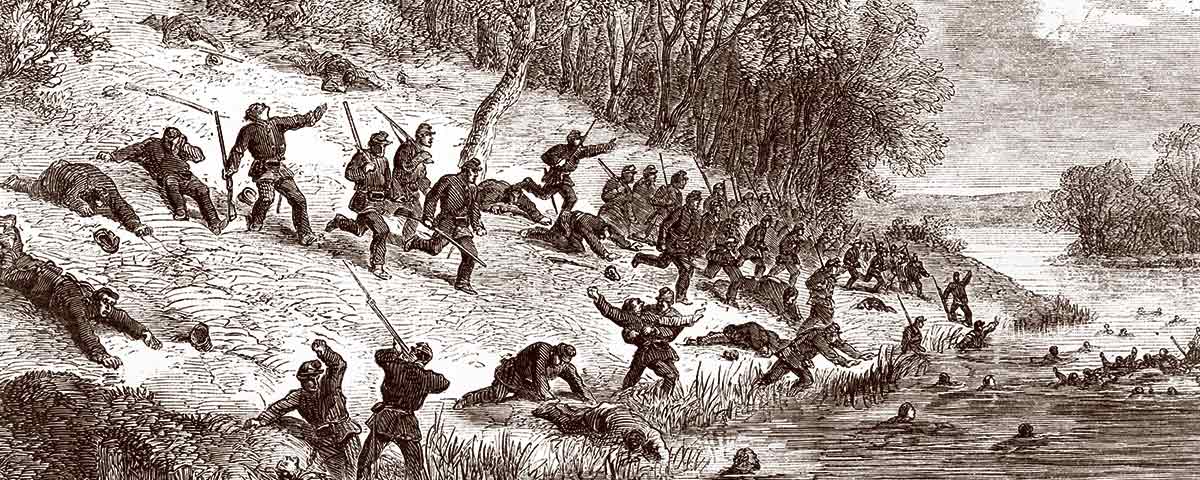

It was too much for the pressed Yankees. Cogswell made an effort to conduct an orderly withdrawal, but it was too late. One Rebel noted, ‘a kind of shiver ran through the huddled mass upon the brow of the cliff; it gave way; rushed a few steps; then, in one wide, panic-stricken herd, rolled, leaped, tumbled over the precipice!’

The Federals had nowhere to go but into the swollen river. Many of them drowned or were shot as they attempted to swim to Harrison’s Island. Private William Thatcher of the 1st California swam for his life as he could hear ‘balls going ploog in the water’ all around him. ‘I never felt so near death,’ wrote a relieved G.W. Davison of the 15th Massachusetts, ‘in the water, weak, and out of breath, and balls whizzing.’

Many other Federals took what cover they could at the base of the bluff and later surrendered. More than 50 percent of the Union force become casualties, making the Confederate victory as complete as any won by either side during the war.

Material in the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion notes that 49 Union soldiers were killed. Regimental returns, medical records and the many reports of bodies washing ashore along the Potomac in the days following the battle make it clear, however, that the Federal death toll approached 250. The Confederates suffered fewer than 40 killed.

The primary responsibility for the Federal disaster lies with Colonel Baker. Though personally brave, he made several very careless and costly decisions that hindered rather than helped the troops he ordered into battle.

The Southern command structure also had problems resulting from confusion and casualties. Walter Jenifer, Eppa Hunton and Erasmus Burt all were in charge of the Confederate forces at some point, until Winfield Scott Featherston took command and led the climactic assault that drove the Federals into the river at the end of the day.As events played out, Colonel Evans, who remained close to the Edwards Ferry road during the fight, moved troops to Ball’s Bluff at just the right times. Although his force never really outnumbered the Union troops, the pressure they applied was consistent enough to generate positive results for the Confederates despite the confusion caused by the numerous field command changes.

Ball’s Bluff was considered a significant fight in 1861, but by later standards it was a mere skirmish. General Stone later described it as being ‘about equal to an unnoticed morning’s skirmish’ in 1864. But it mattered at the time, and it had serious consequences. To the Confederates it was ‘a splendid success.’ For the defeated Federals, ‘a very nice little military chance’ became ‘that cursed Ball’s Bluff,’ which inspired the inquiry of committees and ruined careers.

Though Baker was primarily to blame, the Republicans who controlled Washington had no desire to smear a Senate colleague and friend of the president. Therefore, the ax landed on Stone’s neck. The congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War was formed partly in response to the debacle.

Stone, who had been a rising star in the Union Army, was grilled by committee members and eventually imprisoned for 189 days, although no charges were ever filed against him. After his release, he served in the Western theater before resigning from the Army in September 1864.

The Joint Committee existed throughout the war, a shadow over the shoulder of Union generals who did not function precisely in the manner the politicians thought they should.

And what of Sergeant Donaldson? Attempting to work his way downriver late in the day, he was captured and spent the night with more than 500 of his comrades in the yard of the Loudoun County Courthouse in Leesburg. Sent to a prison in Richmond, he was aided by his brother, Lieutenant John Donaldson of the 22nd Virginia, who got him released on the condition that he would not leave the city. He was even offered a job in the Confederate postal service, but refused.

In February 1862, Donaldson was exchanged and returned to the war, eventually becoming a captain in the 118th Pennsylvania. He survived the war and attended the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, dying at his home in 1928.

This article was written by James A. Morgan III and originally appeared in the November 2005 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!