ON AUGUST 15, 1945, millions across Japan stared at radios, listening in amazement to their emperor’s voice, reproduced on a 78-rpm phono disc. Hirohito was reading an edict declaring that his military forces would surrender unconditionally. Many listeners missed his meaning—most commoners had never heard an emperor speak and Hirohito, who was using classical Japanese difficult for most of his countrymen to follow, never actually said “defeat” or “surrender.” Afterward, an announcer drove home the god-king’s stunning point. For the first time in Japan’s 2,600-year history, the nation had met defeat.

ON AUGUST 15, 1945, millions across Japan stared at radios, listening in amazement to their emperor’s voice, reproduced on a 78-rpm phono disc. Hirohito was reading an edict declaring that his military forces would surrender unconditionally. Many listeners missed his meaning—most commoners had never heard an emperor speak and Hirohito, who was using classical Japanese difficult for most of his countrymen to follow, never actually said “defeat” or “surrender.” Afterward, an announcer drove home the god-king’s stunning point. For the first time in Japan’s 2,600-year history, the nation had met defeat.

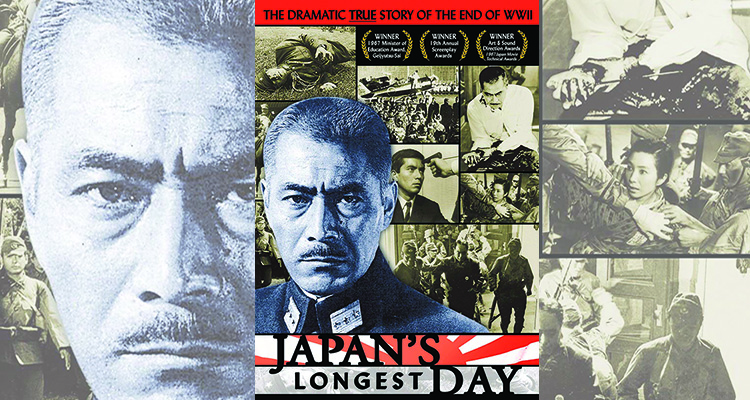

In 1967, Toho Company, Ltd.—famous in America for its Godzilla franchise—released Japan’s Longest Day, an account of the 24 hours before Hirohito’s broadcast. Directed by Pacific War veteran Kihachi Okamoto, whose 39 films include many with World War II themes, Japan’s Longest Day—in the style of The Longest Day, its 1962 Hollywood namesake—featured an all-star ensemble led memorably by Toshirō Mifune, Japan’s John Wayne. The film, closely based on fact, became Japan’s second highest grossing film of 1967.

The title refers to the gripping events between noon August 14, when Hirohito importuned his cabinet to end the war, and the following day’s Gyokuon-hōsō, or “Jewel Voice Broadcast.”

In a 21-minute documentary-style opener, Okamoto portrays the cabinet struggling to answer Potsdam Declaration demands for unconditional surrender, with the only alternative “prompt and utter destruction.” The cabinet splits. A pro-peace faction centers on Prime Minister Baron Kantarō Suzuki (Chishū Ryū). The diehards’ strongest voice is the empire’s war minister, General Korechika Anami (Mifune). Reluctant at best to accept surrender, Anami argues that the Potsdam Declaration does not offer adequate assurance that the Allies will permit the emperor to keep the throne. The cabinet, he insists, must force the Allies to be clear on this point. “Because if that is not the case,” the general tells the cabinet, fist on the hilt of his long sword, “we must fight to the last man.”

Unable to decide even with Hiroshima and Nagasaki in radioactive cinders and the Soviets invading Manchuria, the cabinet finally meets with the emperor to seek resolution. Suzuki, then Anami, pleads his case. As Hirohito (Hakuō Matsumoto) rises to respond, Okamoto superimposes a clock, then the film’s title. The documentary structure falls away and Japan’s Longest Day plays out as a drama intercutting the cabinet and emperor as they make their final deliberations, the push to record and air the capitulation edict, and hardcore militarists plotting to keep the emperor’s speech from reaching the Japanese people.

“It is impossible to continue to prosecute this war,” Hirohito tells the cabinet, voice halting as he tries to control his emotions. “No matter what happens to me . . . my people . . . save my people. I can no longer endure letting them suffer any longer.” Kihachi photographs this scene carefully, hiding Hirohito’s face. Besides showing deference to the emperor, this framing focuses our attention on Anami’s reaction to his sacred leader’s declaration. When the rest of the cabinet is bursting into tears, the dry-eyed Anami, who knows of the would-be coup, wears an expression of austere resignation. His heart is with the hardcore militarists, but to join the resistance would be to defy his emperor, and he is too traditional a man to do so.

For the rest of the film, characters race one another and time. The cabinet wrangles over the edict’s wording. Staff-level officers deduce what is underway and plot a coup d’état. Commanders at key air bases Atsugi and Kodama vow to fight on by sending kamikazes against an American fleet off the coast. Anami, after sternly instructing his staff to obey the emperor, goes into foreboding seclusion.

Okamoto’s juxtapositions can be startling. Civilians, including many schoolchildren, throng an airfield to sing an anthem of support for pilots preparing to fly to their deaths. The song continues as the perspective cuts to officials placing the finished edict before the emperor, who signs it. The recording session takes place; the emperor’s men hide the disk at the Imperial Household Agency. The plotters invoke the impending kamikaze attacks as they plead with General Takeshi Mori (Shōgo Shimada), commander of the 1st Imperial Guard Division, to join their coup. Rebuffed, the conspirators murder Mori, forge orders in his name, and transmit them to the empire’s remaining forces. Imperial Guard detachments surround the palace and ransack the royal household looking for Hirohito’s surrender recording.

The coup begins to fall apart. The guardsmen cannot find the record. The forged orders’ origins come to light. General Shizuichi Tanaka (Kenjiro Ishiyama), commander of the Eastern District Army, arrives at the palace to stop the plot for good. In counterpoint, Anami, alone but for two young subordinates, resolutely prepares to commit seppuku—self-disembowelment. He tells his companions, who are there to witness his suicide, that they must help to rebuild Japan. “Each and every Japanese must stand by their station, live on, and work earnestly,” Anami urges the pair. “In no other way can the nation be rebuilt.”

Anami kills himself. Separately, so do the plotters, whose bodies are on screen as we hear the announcer’s voice introducing the emperor’s recording. Japan’s Longest Day ends not with an outright rejection of militarism—70 years on, Japan has yet to come to terms with what its aggression wrought—but with the suggestion that for a new Japan to rise, the old Japan had to die.

Originally published in the September/October 2015 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.

Image credit: Toho Company/The Kobal Collection