To some it was the “Magnificent Leviathan,” to others “Mitchell’s Folly.” Its detractors considered the giant triplane a waste of taxpayer money, and dismissed it as reflection of the outsized aspirations of air power advocate Brigadier General William “Billy” Mitchell. Popularly known as the Barling Bomber, it was the largest aircraft of its day, and although ultimately a failure, it presaged a future in which even larger bombers would become the mainstay of American air power.

Walter H. Barling, the airplane’s British designer and namesake, had already fathered the Tarrant Tabor, a large experimental six-engine triplane bomber built in May 1919 for the Royal Aircraft Establishment, when he took on this new project. The Tabor turned out to be so heavy and out of balance that it nosed over on the takeoff roll for its maiden flight, killing its pilots. But Mitchell, then assistant chief of the U.S. Army Air Service, was impressed with the basic concept. He was convinced that such huge planes, loaded with bombs, were capable of sinking battleships. Moreover, he believed the Army Air Service deserved a budget that would fund them.

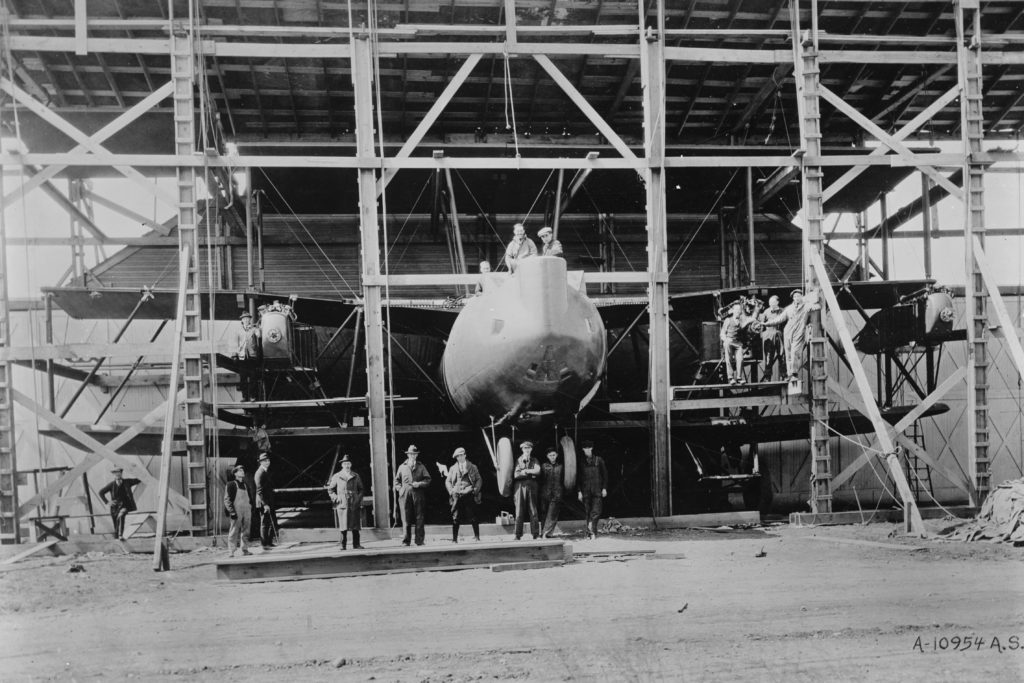

After Barling emigrated to the United States, in 1920 Mitchell approved specifications for two prototypes of a similar triplane to be designed by Barling and officially designated the Experimental Night Bomber, Long Range (XNBL-1). The Witteman-Lewis Co. of Teterboro, N.J., was contracted to manufacture the planes’ components, with the stipulation that war surplus Liberty engines were to be used. The parts were delivered by train from New Jersey to the U.S. Army Engineering Division at McCook Field near Dayton, Ohio, where the planes were actually constructed. Due to this splintered system— with components manufactured 400 miles from where they would be assembled—there were serious problems with parts not fitting together properly. After it was discovered that the fabric wings had trapped rainwater, distorting the initial weight and balance measurements, a large hangar was built at old Wright Field at a cost of $700,000, so that construction could continue unimpeded by the weather.

While Barling labored on the first bomber and monitored manufacture of its parts over the next three years, Mitchell forged ahead, eager to prove his assertions about the need for aircraft capable of combating warships. His July 1921 sinking of the German battleship Ostfriesland and three other ships seemed to validate his hypothesis. But when Kansas Congressman Daniel R. Anthony learned about the Barling Bomber’s cost, initially estimated at $375,000 though later increased to $525,000, he objected. Congress canceled further development work as well as the second prototype.

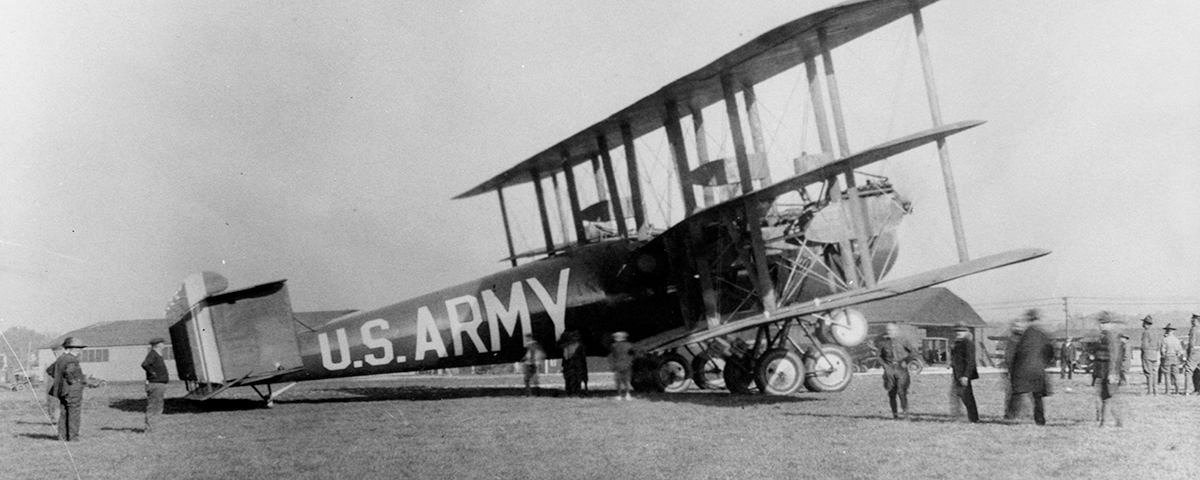

The bomber’s vital statistics, in addition to its cost, staggered the public’s imagination. The largest heavier-than-air bomber of that period, it featured three mammoth wings and an empennage with four rudders and an elevator plane controlled by the pilot, held together in a box-like framework resting on a fixed tail skid. Powered by six 420-hp Liberty 12A liquid-cooled engines—four tractors and two pushers mounted behind the two inboard tractor engines—it was 65 feet long and 27 feet high, with a wingspan of 120 feet. Its empty weight was 27,703 pounds, with a gross weight of 32,203 pounds and a maximum takeoff weight of 42,569 pounds. Top speed was 96 mph and cruising speed was 61 mph; its range with a full bombload of 5,000 pounds was approximately 170 miles. It was also equipped with seven .30-caliber defensive machine guns.

The Barling was meant to have a crew of six: two pilots in an open cockpit in the nose and a flight engineer seated behind them, with separate compartments for a navigator and radio operator, and a bombardier positioned on a small bicycle seat in the lower nose under the pilots. The bombardier had to send requests for course or speed changes to the cockpit via a pulley and rope assembly.

The main cockpit had a single control wheel and one throttle lever for all six engines that the pilot pushed forward or side-to-side to control the engine speeds for taxiing or to assist in making turns in the air. An unusual 10-wheel adjustable landing gear with oleo struts distributed the huge plane’s weight on the ground, a concept that is seen on some of today’s large aircraft. Dual wheels under the nose helped keep it from pitching too far forward during takeoff, as had happened with the Tarrant Tabor. Other futuristic features included reinforced bulkheads and special materials in the fuselage to help protect the plane and crew from anti-aircraft fire.

The day finally came for Barling’s “monster” to take to the air. On August 22, 1923, test pilots Lieutenants Harold R. Harris and Muir S. Fairchild, accompanied by civilian flight engineer Douglas Culver and Barling himself, taxied out onto the grass runway at Wright Field and took off in 960 feet after a run of only 13 seconds. An enthusiastic Barling described his reactions:

You can perhaps imagine my thoughts after these many years of intense study, repeated discouragement, worry, nervous tension, and hopeful expectation, on hearing the cheery call of Lieutenant Harris, “Let’s go!”

I was not anxious about the ship’s ability to fly. It has been observed that the engine mounts were absolutely rigid even at low engine speed, which tests this feature better than higher speeds. We knew, too, from previous tests that the wing structure and fuselage could be relied upon for strength and rigidity. With these points in its favor the only uncertainty lay in the controls and landing gear. As for the latter, I had great faith in the oleo legs.

I stationed myself in the rear upper gun cockpit. From here I could see each of the engines, the wings, fuselage and tail. We made the turn at the takeoff point. I could not but marvel at the ease with which the great ship made the turn. She can turn on the ground on an axis inside of a wingtip and almost on one undercarriage. I was a bit worried, however, that the abrupt turn would injure the skid.

From my lofty aerie I surveyed the structure of my gigantic plane and was glad that I had been given this part to write in this romantic manuscript of human accomplishment.

Harris and Fairchild flew the bomber to several Midwest airshows, including the International Air Meets in St. Louis in 1923 and 1924. Everywhere it went, the giant Barling attracted attention. It set duration and altitude records for lifting payloads of 4,400 pounds to 6,800 feet and 6,600 pounds to 5,344 feet, but its slow top speed and modest range with a full bomb-load, not to mention the engines’ inability to get the plane to its estimated ceiling of 7,725 feet, were major disappointments. Those shortcomings were highlighted when an appearance at Bolling Field in Washington, D.C., had to be canceled because the bomber couldn’t get over the Appalachians with a full load of fuel.

Altitude, load and range limitations, as well as cost overruns, ultimately doomed the XNBL-1. The Barling’s last flight was in 1925, the same year that Billy Mitchell was court-martialed for his criticisms of the military.

The big bomber was dismantled, and its components were stored in a warehouse at the Fairfield Depot. When Major Henry H. “Hap” Arnold discovered the plane’s remnants there in 1929, on becoming the depot commander, he ordered them burned. All that remains today are two wheels from its revolutionary landing gear, housed at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson in Ohio.

The Barling Bomber had served as a lingering embarrassment to Arnold and others like Mitchell who had seen its unique potential despite its high cost and disappointing “built-in headwind” performance. In his memoir Global Mission, Arnold wrote: “People generally do not understand that a plane like that cannot be classed as a one hundred percent failure. It is true, the Barling itself failed to fly as planned, but many aeronautical engineering problems were solved by it. Records from wind-tunnel tests, theoretical analyses of details of assemblies, and newly devised parts on paper are all right, but there are times when the full-scale article must be built to get the pattern for the future.”

Earl H. Tilford Jr., a noted strategic bombing historian who studied the Barling episode in great detail, agreed with Arnold’s assessment. He pointed out that “progress cannot always be measured in unqualified successes. The Barling Bomber may have been a failure but was also a bold step in the attempt to develop a large multi-engine aircraft.”

Originally published in the September 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.