The Union found to its chagrin that John Pope and the war in the east were not a good fit

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]pring 1862 had begun with such promise for the North. The “Young Napoleon,” Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, had methodically organized and, by April, launched an 80-mile thrust by the Army of the Potomac up the Virginia Peninsula to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond and thereby, he hoped, end the year-old war in one stroke. McClellan’s grand effort, however, would be slowed and eventually halted by miserable weather, his own overly cautious leadership, and an admirably stubborn defense by the outnumbered Confederates.

By the summer, after the Seven Days fighting had wrecked McClellan’s aspirations, the Federal army faced a choice of staying stalled outside Richmond or evacuating the Peninsula and returning north. President Abraham Lincoln presciently surmised Robert E. Lee would likely use McClellan’s setback as a springboard for a counter-campaign against Washington, D.C., and he began assembling a force to block any such effort. Gathering forces from several widespread Union armies, including ordering some units from McClellan’s own army to join it, Lincoln created the Army of Virginia to form in the vulnerable area west of the capital. He then tapped a “Western general,” Maj. Gen. John Pope, to command it.

Just as McClellan had on the Peninsula, Pope would by September find himself direly tested and then overwhelmed by Lee and his accomplished subordinates, Generals Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet.

John Pope came from the West with a chip on his shoulder. His singular accomplishment had come back in April with the capture of the Mississippi River strongholds of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Mo., bagging 5,000 prisoners (though he boasted of 7,000), 158 cannons, and extensive war supplies—all without losing a man. Now he was being called east to build an army out of the three bedraggled forces that Confederate Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson had chased through the Shenandoah Valley that spring. His command of the Army of the Mississippi had suited him, but this new Army of Virginia promised to be a most troublesome command for the 40-year-old Kentuckian: “I especially disliked the idea of service in an army of which I knew nothing beyond the personnel of its chief commanders, some of whom I neither admired nor trusted,” he would declare. Still, Pope understood he was there to bring new energy and a harder tone to the war in Virginia.

A member of West Point’s Class of 1842, Pope had served capably (two brevets) in the Mexican War. As a Republican in the antebellum Army he was a rarity, but with the coming of war his politics helped jump him from captain to brigadier general to major general. A journalist wrote: “In person he was dark, martial, and handsome—inclined to obesity…possessing a fiery black eye, with luxuriant beard and hair. He smoked incessantly, and talked imprudently.”

McClellan’s army was still mired in the Seven Days Battles when Pope assumed command of the Army of Virginia on June 27. The forces he had at his disposal comprised Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont’s Mountain Department, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ Department of the Shenandoah, and Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s Department of the Rappahannock. In the Army of Virginia, those departments would be corps. Although their commanders were senior in rank to Pope, only Frémont was affronted. There was bad blood there, and Frémont asked to be relieved. The authorities in Washington were happy to oblige.

Major General Franz Sigel assumed Frémont’s command, now designated 1st Corps. Sigel’s troops included Louis Blenker’s German division, which had gained infamy as the “Thieving Dutchmen” during the Valley fighting. Blenker was gone now, his men scattered among Sigel’s division commanders—Robert C. Schenck, the former Ohio congressman who had retreated infamously at First Bull Run the previous July; Adolph von Steinwehr, who had served without notice under Blenker; and Carl Schurz, a German revolutionary who, like Steinwehr, awaited his first test of battle.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]John Pope came from the West with a chip on his shoulder.[/quote]

Sigel, a lieutenant once under the Grand Duke of Baden and an 1848 insurgent, had compiled a spotty record out West and held his post due mostly to his connections in the German-American community. He was of high temper and large gesture—in his long cloak and wide-brimmed hat he looked, said Maj. Gen. Alpheus Williams, “as if he might be a descendant of Peter the Hermit.” Whatever Pope thought of Frémont, however, he thought far worse of Sigel, calling him “the God damndest coward he ever knew.” Sigel, equally blunt, appraised Pope as “affected with looseness of the brains as others with looseness of the bowels.”

The 2nd Corps belonged to Banks. A Massachusetts governor and congressman, and a Republican stalwart, Banks represented the purest expression of a political general. He had been derided as Stonewall Jackson’s commissary in the Valley that spring, but in fact managed a retreat that saved his men if not their supplies. His division heads were Alpheus Williams, the former militia officer whose command promise survived the Valley debacle, and West Pointer Christopher Columbus Augur.

McDowell’s 3rd Corps was the largest, soundest element of Pope’s army, with divisions led by Rufus King and James B. Ricketts. King was in his first command, and Ricketts, the veteran artilleryman wounded and captured at First Bull Run, was leading infantry for the first time. The martinet McDowell still looked to erase the Bull Run stain from his record, and remained as unpopular with the troops as ever. At a review his horse threw him, and from the ranks, sotto voce, came a call for three cheers for the horse.

Pope’s brigade commanders were a mixed lot. In McDowell’s and Banks’ corps such men as Abner Doubleday, Marsena R. Patrick, John Gibbon, Samuel S. Carroll, Samuel W. Crawford, George H. Gordon, and George Sears Greene would go on to achieve notice (or better) in the Army of the Potomac; less would be said of those in Sigel’s corps.

The variegated elements of the Army of Virginia lacked any shared experience, and what combat record they had was poor. At first glance, Pope said, his new command was “much demoralized and broken down, and unfit for active service….Of some service they can be, but not much just now.” Staff man David Strother entered in his diary: “There seems to be a bad feeling among the troops—discouragement and a sense of inferiority which will tell unfavorably if they get into action.” They had not been paid for months, and desertion was endemic; a thousand officers were absent without leave.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]At first glance, Pope said, his new command was ‘much demoralized and broken down, and unfit for active service’[/quote]

Angered at the lack of spirit and the defeatist attitude, Pope issued a blunt address to his men on July 14. “I have come to you from the West,” he proclaimed, “where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found.” Warming to his subject, he went on to decree that he was “sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of ‘taking strong positions and holding them,’ of ‘lines of retreat,’ and of ‘bases and supplies.’ Let us discard such ideas.” Strong positions should be taken in order to launch attacks, he said. Focus on the enemy’s lines of retreat, not your own. “Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.”

Marsena Patrick wrote that Pope’s address struck him as “very windy & somewhat insolent.” To George Gordon it implied “a weak and silly man.” Brigadier General John P. Hatch said he would “be astonished if with all his bluster anything is done.” But in the ranks many recognized Pope’s target as the officer corps and many agreed with him. In his diary, a cavalryman wrote: “Pleased with Gen’l Pope’s address. He seems an energetic—‘go ahead’ man—such a one as this department needs, and has ever needed, and has never had! Our Potomac Generals paid too much attention to reviews and inspections and parades….We have been out-generaled here.”

It was well understood that Pope’s address skewered McClellan’s way of making war. In Washington, Pope missed no chance to denounce the Young Napoleon. Dining with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, he claimed McClellan’s “incompetency and indisposition to active movements were so great” that should he, Pope, ever need assistance in his operations, “he could not expect it from him.” He urged Lincoln to relieve McClellan without delay. He testified to the Committee on the Conduct of the War on McClellan’s failings. And he spread his poison among his own generals. Gordon recalled a talk at headquarters in which Pope described mismanagement on the part of McClellan, “for whom he seemed to entertain a bitter hatred.”

‘They quarrel like cats and dogs’

Squabbles, intrigues, jealousies, and self-serving machinations among America’s generals were certainly not limited to McClellan’s and Pope’s armies and to the American Civil War; in fact, such “un-general-like” behavior is as old as the Republic itself. In 1778, for example, John Adams, disgusted at the continuous and petty in-fighting of George Washington’s Continental Army generals, wrote to his wife, Abigail, that he was “worried to death with the wrangles between military officers, high and low. They quarrel like cats and dogs. They worry one another like mastiffs, scrambling for rank and pay like apes for nuts.”

Victory in the American Revolution failed to stop the “dogfights” in what became the new United States Army. In the 1790s, Army commander Maj. Gen. “Mad Anthony” Wayne was constantly undermined, second-guessed and back-stabbed by his second-in-command and fellow Revolutionary War veteran, Brig. Gen. James Wilkinson (who, not incidentally, was eventually discovered to have been a paid secret agent of the Spanish crown). Wayne’s attempt to court-martial his insubordinate subordinate ended prematurely with “Mad Anthony’s” death in 1790; four years later Wilkinson became senior officer of the U.S. Army.

The War of 1812 prompted a notable “dogfight” between two American generals concerning which officer held seniority over the other that continued for decades. Winfield Scott and Edmund P. Gaines, both breveted major general in 1814, each claimed to be the Army’s senior officer. However, the two officers’ unseemly and very public “scrambling for rank” so disgusted President John Quincy Adams that when the position of commanding general of the U.S. Army became open in 1828 he passed over both of the scandalously feuding officers, instead appointing Alexander Macomb. Yet Scott eventually had the last laugh—he became commanding general when Macomb died in 1841. Gaines, no doubt still fuming over the success of his bitter rival, died in 1849.

Scott held the Army’s top slot for an unprecedented 20 years until, ailing and 75 years old, he was forced out of the position in November 1861. The ambitious young officer who replaced him as the Army’s commanding general, and whose behind-the-scenes scheming and blatantly self-serving use of influential political allies forced Scott out, was…Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan.

–Jerry Morelock

Pope’s address was followed by the notorious General Orders No. 5, which on paper promised to inflict the harshest treatment on Virginia’s civilians. Pope would tell General Jacob Cox that the orders were dictated, in substance, by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. But to all and sundry, the orders were Pope’s. The most draconian of them would not be carried out, but nothing lessened their initial impact. Robert E. Lee was roused to cold fury. “I want Pope to be suppressed,” he told Stonewall Jackson. “The course indicated in his orders if the newspapers report them correctly cannot be permitted.” He strengthened Jackson “to enable him to drive if not destroy the miscreant Pope.”

Pope’s general order, permitting the army to “subsist upon the country,” was interpreted by the rank and file as a license to steal, and Patrick was outraged. The troops, he told his diary, “believe they have a perfect right to rob, tyrannize, threaten and maltreat any one….This Order of Pope’s has demoralized the Army & Satan has been let loose.” An officer of Banks’ reported: “The lawless acts of many of our soldiers are worthy of worse than death. The villains urge as authority, ‘General Pope’s order.’”

Major General William Franklin, who knew Pope from the old Army, told his wife: “We look with a good deal of interest upon Pope’s movements, having a shrewd suspicion that if he does not look out he will be whipped. After his proclamation he deserves it.” Major General Fitz-John Porter too was acquainted with Pope, telling the New York World that he was “a vain man (and a foolish one)…who was never known to tell the truth when he could gain his object by a falsehood.” Porter wrote Washington insider Joseph C.G. Kennedy, “I regret to see that Genl. Pope has not improved since his youth and has now written himself down, what the military world has long known, an ass.” Pope’s army would only get to Richmond “as prisoners.”

When he learned Jackson was stalking Pope, McClellan declared that within a week “the paltry young man who wanted to teach me the art of war” would be in retreat or whipped. “He will begin to learn the value of ‘entrenchments, lines of communication & of retreat, bases of supply etc.’” McClellan issued orders to his own army that “will strike square in the teeth of all [Pope’s] infamous orders & give directly the reverse instructions to my army—forbid all pillaging & stealing & take the highest Christian ground for the conduct of the war—let the Govt gainsay it if they dare.”

McClellan’s prediction that Pope would be quickly in retreat or whipped wasn’t too far off the mark.

As he awaited resolution of the Army of the Potomac’s dilemma after the Seven Days, Pope posted his army along the Rapidan River’s north bank. Should McClellan march on Richmond from Harrison’s Landing, Pope felt secure. If he evacuated the Peninsula, however, Pope had reason for much concern until their two armies were united.

In mid-July, Lee sent Jackson to keep an eye on Pope and to guard Gordonsville, Va., and the Virginia Central Railroad, a vital link to the Shenandoah Valley. On July 27 he reinforced Jackson with a division, to enable him to “strike your blow and be prepared to return to me when done if necessary.” His boldness was rewarded. With Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s force arriving at Aquia Landing near Fredericksburg, as well as evidence of an evacuation and abandonment of the Yankee toehold at Malvern Hill, Lee knew it meant McClellan would not be reinforced. He responded by further strengthening Jackson’s hand as he also prepared to send James Longstreet’s Wing north. He needed to dispose of the Army of Virginia before the two Yankee armies could combine and dispose of him.

After Pope pushed Banks’ 2nd Corps forward to Culpeper, some 20 miles north of Gordonsville, Jackson too moved toward Culpeper. On August 9, Pope sent Nathaniel Banks an order, delivered verbally by a staff colonel. Banks lacked military credentials, but as a veteran politician he well knew that a verbal directive was worth far less than the paper it should have been written on. An aide took down the order and read it back for the colonel’s approval: “Genl Banks to move to the front immediately, assume comd of all the forces in the front—deploy his skirmishers if the enemy approaches and attack him immediately as soon as he approaches—and be reinforced from here…” Afterward Pope insisted his order obliged Banks only to take up a defensive position and wait to be reinforced.

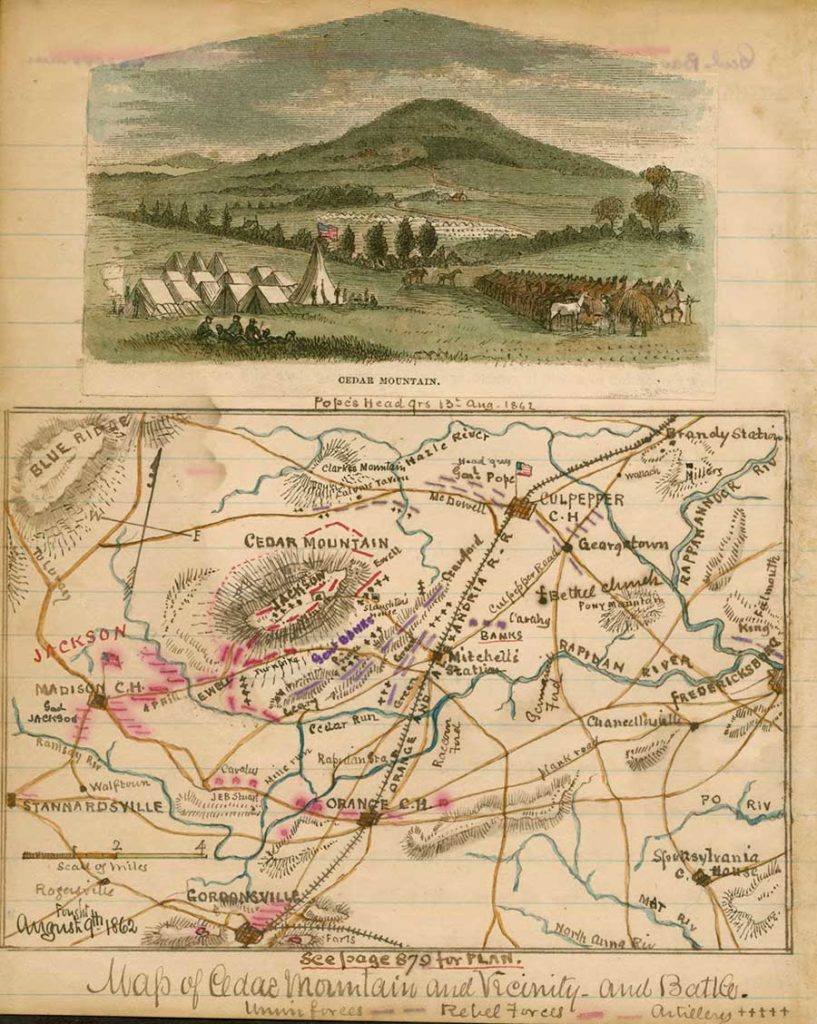

Knowing Jackson was close by, Banks positioned his force near Cedar Mountain, some seven miles south of Culpeper. Pope intended a general advance that day, with Sigel’s 1st Corps and half of McDowell’s 3rd moving forward in support of Banks’ 2nd. Sigel fumbled his marching orders, McDowell lingered in the rear, and so on August 9 Banks found himself alone with Jackson. As the Battle of Cedar Mountain unfolded that day, he would be outnumbered 15,000 men to 9,000.

The battle was a stalemate most of the day, but began to turn in the Federals’ favor by late afternoon. With the Confederate left on the verge of collapse about 5 p.m., however, counterattacks by Jackson, Jubal Early, and A.P. Hill sent Banks’ forces into disarray and retreat.

At dusk, one more adventure awaited the Union high command. Pope had reached the scene, roused by the thunderous gunfire, and was conferring with his generals when Rebel cavalry made a sudden dash into their lines. Chaos erupted. There was a mad dash for horses, and generals and staffs pelted away through the woods in every direction. “[T]he skedaddle became laughable in spite of its danger,” recalled Alpheus Williams.

Cedar Mountain was Nathaniel Banks’ battle from start to finish. He believed (properly so) that Pope’s verbal order required him to take the offensive. He might have confirmed the order, if just to learn whether Ricketts was his support. Banks was determined to settle scores with Jackson for his Valley trials, and believed his corps plus Ricketts’ division would be enough. “The day we have waited for so long has at last come,” he had written his wife. “I am glad.”

Fifty-six of Banks’ 88 officers became casualties that day, with the Federals suffering 2,403 total to the Confederates’ 1,418. There was “a good deal of hard feeling between the officers of Genl Banks and Head Quarters—they say that they were needlessly sacrificed.” Banks satisfied himself that he had given Stonewall a check (two days after his victory, in fact, Jackson pulled behind the Rapidan to regroup). Banks told his wife, “My command fought magnificently,” which was true. “It gives me infinite pleasure to have done well,” which was self-flattery.

The Army of Virginia’s check at Cedar Mountain rudely awakened Pope to his danger. He telegraphed General-in-Chief Henry Halleck: “I am satisfied that one-third of the enemy’s whole force is here, and more will be arriving unless McClellan will at least keep them busy and uneasy at Richmond.” Halleck sent a sharp dispatch to McClellan: “There must be no further delay in your movements. That which has already occurred was entirely unexpected, and must be satisfactorily explained.” Halleck told his wife, “I have felt so uneasy for some days about Genl Pope’s army that I could hardly sleep. I can’t get Genl McClellan to do what I wish.”

McClellan told his wife he found Halleck’s telegram “very harsh & unjust,” and in any event, Pope deserved what was coming to him. “I have a strong idea that Pope will be thrashed during the coming week—& very badly whipped he will be & ought to be—such a villain as he is

ought to bring defeat upon any cause that employs him.” Thus was McClellan’s frame of mind as he began moving the Army of the Potomac from the Peninsula to join Pope’s Army of Virginia.

It must be done by the book, McClellan ruled—a careful, calculated disengagement from a powerful, threatening enemy. Halleck’s evacuation order was dated August 3, but rather than beginning a march for Fort Monroe while removing the sick and the army’s baggage by water, McClellan didn’t begin the march for 10 days. There was no help for this—“Our material can only be saved by using the whole Army to cover it if we are pressed.” Porter’s 5th Corps left Harrison’s Landing on August 14, reached Fort Monroe on August 18, and shipped out for Aquia Landing on August 21. The corps that followed waited for shipping space. It was August 26 before the last of them began to embark.

On August 13, as McClellan husbanded his forces at Harrison’s Landing to fend off attack, Lee ordered the other wing of his army, under Longstreet, to join Jackson on the Rapidan. Lee himself left on the 15th to take command of the evolving campaign. He left two infantry divisions to guard Richmond and a brigade of cavalry to keep an eye on the Army of the Potomac. For more than four months on the Peninsula, George McClellan had faced a phantom Rebel army of his own devising. Now, as unknowing as ever, he faced the ghost of a Rebel army.

McClellan felt sure the troops realized he was not responsible for the retreat. “Strange as it may seem the rascals have not I think lost one particle of confidence in me & love me just as much as ever.” But he viewed once-favored lieutenants with less favor. William Franklin and Baldy Smith lacked energy and initiative and “have disappointed me terribly.” This rounded out his estrangement from Smith. As to Franklin, he no longer doubted his loyalty—a distrust dating back to Lincoln’s ad hoc war council in January—but “his efficiency is very little.” Only Fitz-John Porter still earned McClellan’s unwavering admiration.

Halleck had promised him command of the two armies as soon as they were united, but McClellan did not hurry north to claim the post. He watched from afar, expecting Pope to come to grief…and expecting to be called to pick up the pieces and once again save the Union. On August 21

he was elated to find his plan working. “I believe I have triumphed!!” he wrote Ellen. “Just received a telegram from Halleck stating that Pope & Burnside are hard pressed—urging me to push forward reinforcements, & to come myself as soon as I possibly can!….Now they are in trouble they seem to want the ‘Quaker,’ the ‘procrastinator,’ the ‘coward’ & the ‘traitor’! Bien…”

Adapted with permission from Lincoln’s Lieutenants: The High Command of the Army of the Potomac, by Stephen W. Sears (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April 2017)

‘Stay West, Young Man!’

Nothing good ever seemed to happen to John Pope whenever he ventured too far east of the Mississippi River. After his army’s setback at Cedar Mountain, Pope failed miserably at the Second Battle of Bull Run. Militarily outgeneraled by Robert E. Lee and politically outmaneuvered by his Union rival, George McClellan, Pope was relieved of command September 12, less than two weeks after the stunning Confederate victory. Yet instead of being stripped of his rank and cashiered from the Army—like his unfortunate subordinate, Fitz-John Porter, whom Pope unfairly blamed for losing the battle—Pope retained his general’s stars and was sent back west.

For nearly the next quarter-century, Pope served with significant success as commander of various Western military divisions and departments, from the Mississippi River to the California coast. Perhaps predictably, the notable exception to Pope’s Western service was another ill-fated sojourn “back east” when he was appointed in April 1867 during Reconstruction as commander of the Army’s 3rd Military District, encompassing the states of Georgia, Alabama, and Florida, with headquarters in Atlanta.

However, Pope’s energetic imposition of Radical Republican policies on the defeated South clashed with the more moderate stance of President Andrew Johnson. The president relieved Pope of command on December 28, 1867, and the again-disgraced general headed back west (stopping in Detroit to command the Department of the Lakes from January 1868 to April 1870).

In the West, Pope proved far more adept at achieving success against various Indian tribes than he did fighting Lee’s Confederates. Yet, virtually all of Pope’s acclaimed Indian Wars victories resulted from the skill and perseverance of talented subordinate field commanders who actually conducted the campaigns and operations, notably those against the Dakota Sioux, Comanche, and Apache tribes. In fact, it was an Indian uprising begun in August 1862 by the Dakota Sioux in Minnesota that prompted Pope’s return to the West immediately after his September 12, 1862, relief from Army of Virginia command. Pope commanded the Department of the Northwest (encompassing the states or territories of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, Nebraska, and the Dakotas) from September 16 to November 28, 1862, although the decisive victory over the Sioux was won by his field commander, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley.

Subsequently, Pope’s Western commands were: Military Division of the Missouri (February 4 to June 27, 1865); Department of the Missouri (June 27, 1865, to 1866 and 1870-1883); and the vast Military Division of the Pacific (November 30, 1883, to March 16, 1886). Pope’s last division command, in addition to Pacific Coast states and territories, notably included Arizona and New Mexico territories during the campaign that resulted in the final defeat of Geronimo and the successful conclusion of the Apache Wars.

Pope retired from the Army on March 16, 1886, at the rank of Regular Army Major General, having been promoted on October 26, 1882. That promotion, elevating an officer best known for presiding over one of the worst defeats suffered during the Civil War, later prompted Ezra J. Warner in his influential collection of Civil War Union generals’ biographies, Generals in Blue, to observe: “[Pope’s promotion] proving, if nothing else, that seniority in that era would win out over all imaginable obstacles.” The National Tribune, founded in 1877 in Washington, D.C., to support the Grand Army of the Republic and publish veterans’ accounts of the war, serialized Pope’s The Military Memoirs of General John Pope from February 1887 through March 1891.

Pope died September 23, 1892, at the quarters of his brother-in-law, former Civil War General Manning F. Force, at the Ohio Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Sandusky, Ohio. Fittingly, given his abysmal track record in the East versus his success in the West, John Pope is buried in St. Louis’ Bellefontaine Cemetery and lies under a modest, starkly plain, small, rectangular granite headstone (horizontally positioned just above ground level) inscribed: “Sacred to the Memory of John Pope, Major-General, U.S. Army, 1822–1892.”

Although Pope’s grave lies within “spitting distance” of the Mississippi River, which flows by only several hundred yards away, it is still safely west of it.–Jerry Morelock