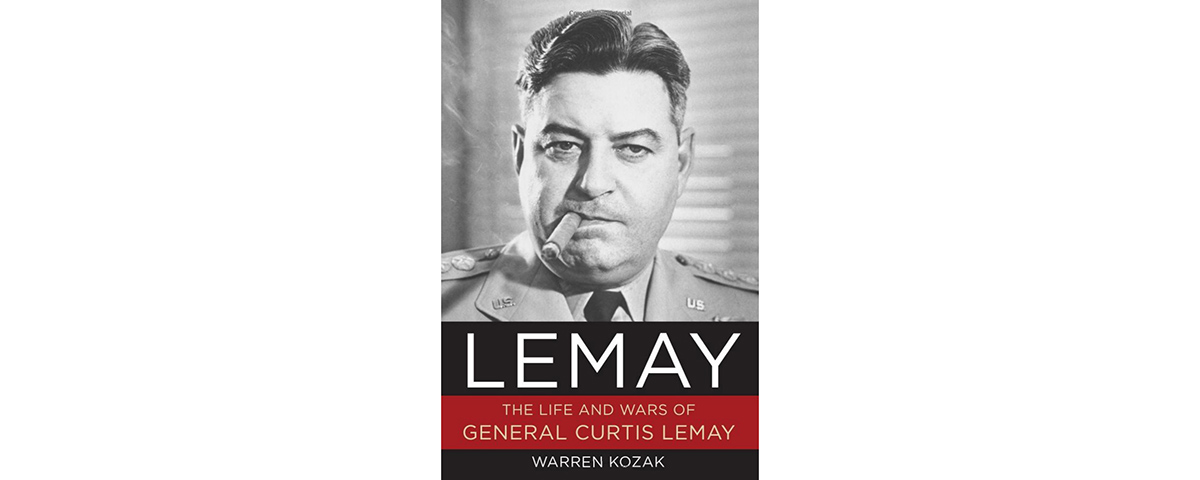

LeMay: The Life and Wars of General Curtis LeMay

by Warren Kozak, Regnery, Washington, D.C., 2009, $27.95.

Curtis LeMay remains one of the most controversial figures in American history. His reputation as an unrepentant destroyer of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japanese cities, as well as his decidedly un-PC attitude toward thermonuclear war while he was running Strategic Air Command, earned him the lasting enmity of the political left. What’s more, when he died in 1990, his decision to run for vice president in 1968 under segregationist George Wallace still colored the perceptions of his contemporaries.

Yet LeMay had proved to be one of the few indispensable military leaders of the 20th century. He was almost solely responsible for saving the high-risk Boeing B-29 bomber from failure, which could have destroyed not only General Hap Arnold but also the prospect of an independent U.S. Air Force. Even today, two decades after his death, in the minds of many Americans Curtis LeMay remains the ultimate “operator”—the unrivaled master of strategic air power.

In Warren Kozak’s sympathetic biography the emphasis is upon LeMay the man, and in that context it largely succeeds. But unfortunately Kozak’s book also reminds us that aviation history really needs to be written by aviators, or at least by authors who understand aviation. It’s full of factual errors as well as peculiar phraseology (“bi-wing airplane”), and is bound to confuse some readers new to the subject. There is little understanding of the relationship between squadrons, groups, wings, air divisions, bomber commands or numbered air forces. And often terms are used incorrectly, as when “21st Air Force” is used as a reference to XXI Bomber Command in the Marianas.

But air power purists should not immediately discount Kozak’s work based solely upon its many factual and technical errors. His valuable research includes interviews with LeMay’s daughter as well as colleagues and subordinates, who provide perspective on the man as well as the commander. Considering the vilification that has been heaped upon the late general, a deeper look into his human side is not only welcome but long overdue.

Meanwhile, the definitive LeMay biography is as yet unwritten. At this point the seminal sources remain his 1965 memoir and the authorized biography of 1987. But for anyone interested in what lay beneath the general’s bluff, gruff exterior rather than concentrating on the machines and institutions he wielded so effectively, Kozak’s treatment should come as a welcome change of pace.

Originally published in the January 2010 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.