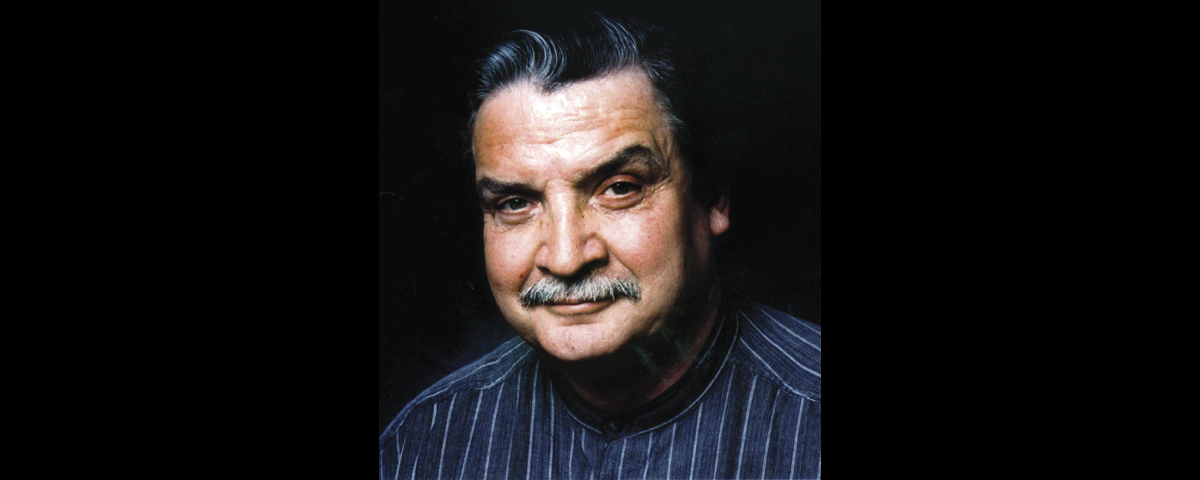

Michael Wallis isn’t afraid to tackle Western icons. He’s written best-selling biographies about David Crockett (David Crockett: The Lion of the West) and Billy the Kid (Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride) and recently signed a contract with W.W. Norton for his 20th book, a biography of outlaw Belle Starr. His latest best seller is The Best Land Under Heaven: The Donner Party in the Age of Manifest Destiny (see review), in which he rounds out the oft-told story of the snowbound emigrants who resorted to cannibalism in the Sierra Nevada during the winter of 1846–47. Wallis recently spoke with Wild West about his Donner Party book and more from his Tulsa, Oklahoma, home overlooking the Arkansas River and Route 66 (he’s also the author of Route 66: The Mother Road).

Why write another book about the Donner Party?

These 1846 pilgrims were the foot soldiers of Manifest Destiny. What I saw in the Donner Party was a chance to emphasize the foibles, the follies, really the sheer arrogance of Manifest Destiny and how in the end even it turned against them. A lot of the horrific yellow journalistic articles ripping into the Donners were written by the establishment press with the backing of other champions of Manifest Destiny, because these people failed to do what they were supposed to do. You’re supposed to go out there and conquer the land. You’re supposed to take it all on. Cut down timber. Dam up that river. Mine that gold. Raise that cabin. Get out there, and it’s your land for the keeping, because there’s no one else out there—forgetting, of course, that three-quarters of that territory belonged to Mexico, and there were a fair amount of Indians out there.

“Instead of becoming the 16th president of the United States, Abe Lincoln might have ended up an entrée.”

Why did you single out party member James Reed?

I found Reed a most interesting character.…[One] new story was the relationship between Abraham Lincoln and Reed. And it put Lincoln in a human light, too, because [the Reeds] were declaring bankruptcy, and [Lincoln] helped his clients squirrel away some money, which [James Reed] put to good use when he was in California…buying up land while putting together rescue parties. And he served a hitch in the military to lead dragoons in the Mexican War. That’s why Reed is so fascinating, because of the multitasking he did and the fact he damn near had Lincoln talked into going with them.

I tell that story in presentations, but I don’t tell who Reed’s lawyer was. I talk about this young prairie lawyer who helped him out, and who almost went, but the lawyer’s wife had a toddler and was pregnant again and didn’t want to go, and this man, always, his whole life, wanted to go to California but never got there.…But maybe that’s a good thing, because instead of becoming the 16th president of the United States, Abe Lincoln might have ended up an entrée.

That always draws a response.

You retraced some of the Donner Party’s route. What was that like?

I learned the Donners went due west out of Springfield, Ill., crossed the Mississippi into Hannibal, Mo., then worked their way down in a southwesterly direction and crossed the Missouri into Independence.

I was on that trail—or close to it as I could get on a rural, two-lane Missouri road—when a storm came up, the likes of which I’d never seen. I mean it was just raining and raining, and I pulled over a few times. Sheets of rain—I couldn’t see. Finally, after a warm shower and a bit of grub, I’m in bed and thinking: Wow, what would that have been like in a whole string of wagons with children and old people and trying to control cattle, dogs, animals? That would’ve been unbelievable.

It became more apparent up in Kearney, Neb., on the Platte. My wife, Suzanne, and I found this spot along the river that was like a jungle—really tall grass, taller than me, and vines and stuff. Suzanne asked, “Are we going to walk through that?” And I said, “Well, we’ve got to, to get to the river.” She took a deep breath and followed me in there, and I pushed and shoved my way through all that and down to the river and soaked it up and made some notes and came out.

By the time we got to the car, we were eaten up with chiggers, as I figured we would be. It was just awful. I asked Suzanne to forgive me, and she did. We drove back to Kearney, to the motel and hot showers. We’ve got medicine, a good steak that night, an air-conditioned room. But what if we were sleeping back there tonight, and were wearing heavy clothes and had screaming babies, dogs, howling, pain?

I don’t want to make a big deal out of it, but I think those experiences are always good.

It was a hell of a trip for them. I don’t want to be judgmental of the Donners when I call them “foot soldiers for Manifest Destiny.” They were people of that time, and they did what they did for different reasons.

Wasn’t Lansford Hastings’ faulty 1845 Emigrants’ Guide to blame for the tragedy?

Well, he’s certainly not guiltless, but I wouldn’t say Hastings is a total black hat villain. James Reed has to take some of the blame, and he did. He was adamant about talking that trail. Certainly cagey, crusty old Jim Bridger lied to those people and didn’t show them the letters that told them don’t go any further. They should have listened to Reed’s old friend James Clyman, who said, “Don’t do this—this is stupid.”

Then, of course, there was that unbelievable winter like no other. And going through all those trials and travails, they’d sometimes reward themselves, saying, “Well, let’s stay an extra day,” even before they got to Truckee Meadows to began the final descent. They stayed too long down there. All that took a toll, and the descendants will tell you they waited way, way too long to begin consuming human flesh. They should have started a lot earlier.

You write: “Survival calls for commitment. Survival was about living. To survive, one must live.”

I tell people it was survival cannibalism, not ceremonial, and they weren’t the first, nor will they be the last, to do it.

If you were trapped in 20 feet of snow and had no food.…You had killed the oxen and horses. You had boiled their hides and made this awful gelatin stew and picked the marrow out of the bones. You had eaten mice and are just now chewing on ponderosa pine cones and bark to chew on something. You’re starving to death, suffering from hypothermia, and your children, your babies, are right in front of you starving to death, too. And you knew in those snowbanks were stores of protein, and those people, damn near all of them, would have said, “Do this—keep yourself alive.”…I don’t know about you, but I’d take my knife out of my sheath, and I would save my life and my children. And that’s what they did.

They also killed and ate a pet dog?

Oh, that scene where Margret [Reed] has to kill Cash, the family dog…and [they] ate all of Cash, one of the girls said, even his paws. That’s pretty rugged.

What drew you to Belle Starr?

The first book written about her was written right after her death in 1889. It was by Richard Fox, publisher of the National Police Gazette. The title was Bella Starr, the Bandit Queen; or the Female Jesse James—so right away you know it was.

The only fairly decent book about Belle is Glenn Shirley’s [1982 book Belle Starr and Her Times: The Literature, the Facts, and the Legends]. I like Glenn, and I think he did some good research. Don’t misunderstand me, but I don’t think he was the greatest writer in the world.

To me it’s all about the research, not wishing to regurgitate what others have said. I tend to stay away from what others have said about Crockett or Billy the Kid or the Donners for that matter. There have been tons written about those two fellows and the Donners, but I always think there’s something new to be said.

There’s so much about Belle that hasn’t been explored, starting with her girlhood in southwestern Missouri. A lot of people think she was just a renegade half-whore. She grew up in a very prominent family, a slave-owning family. She studied Greek, Hebrew, Latin, classical piano. There was a bit of tomboy in her, but she was a Southern belle. But the Civil War and the death of her brother—those are what really snapped her. Once her brother was killed, she stepped over that line and never came back.

As is the case with such characters, there were no white hats or black hats—just a lot of gray hats. Work I’ve uncovered at the Detroit correctional facility where [Judge Isaac] Parker sent her has been interesting. Younger woman with no means would bring their children, their babies, with them, to live with them in prison. Myra Belle apparently mentored quite a lot of these young women and read to the children.

Perhaps writing about Starr won’t be quite as tough?

You never know. I don’t anticipate cannibalism, though. WW