The swift advance of German armies through Belgium and northern France in the opening weeks of the First World War brought with it rumors of alleged atrocities committed by German troops on the civilian populations in those areas. In 1915 the British government released the Bryce Report, a damning account of alleged German outrages. While the report described a variety of incidents, few if any witnesses to them were named, and questions arose as to the authenticity of many of the events. Despite that, the Bryce Report inflamed passions in Britain and France and provided a further rallying cry to defeat the hated Hun. Though most artists and illustrators shied away from the subject of the German atrocities, feeling them too gruesome to depict, one French artist, Pierre-Georges Jeanniot, created a series of 10 etchings in 1915 that showed ravaged women hanging from trees, rape scenes, massacres, maiming, executions, and other violations. French authorities banned the series as too shocking and panic inducing to be shown.

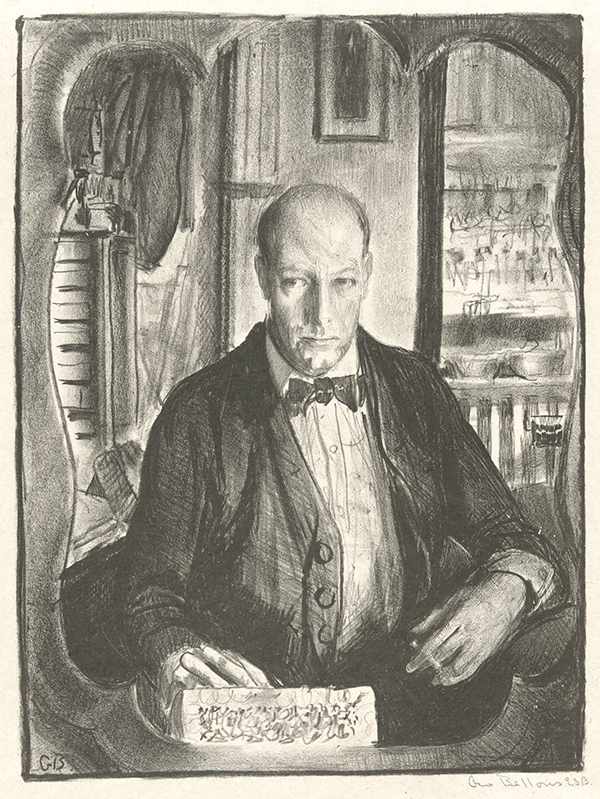

Related: Lithographs from George Bellows’s War Series

While the invasion of Belgium and France had been duly noted in the American press in late 1914, most Americans viewed the conflict in general as a European problem. It would be three more years before the United States entered the war, and even then many of its citizens opposed it, including artist George Bellows, a proponent of New York’s Ashcan school who had become famous for his gritty paintings of boxers in the ring, New York tenements, and other urban landscapes. Bellows soon changed his views on the war, however, and volunteered for the tank corps in 1917. Though he never saw active duty in Europe, he did devote over eight months in 1918 to his War Series—20 lithographs, more than 30 related drawings, and five oil paintings depicting the alleged 1914 German atrocities in Belgium.

THE LITHOGRAPHS FALL INTO three distinct groups, the first showing the fighting and treatment of casualties, the second the capture and treatment of prisoners, and the third brutalities against civilians. One of the most compelling works in the second group is The Murder of Edith Cavell. In it the heroic British nurse, dressed in white against an ominous dark background, descends the staircase from her prison cell on her way to execution in Brussels in 1915 for helping Allied soldiers escape to neutral Netherlands. When a contemporary of Bellows criticized him for creating a scene he had not witnessed, Bellows responded that Leonardo da Vinci did not have “a ticket to the Last Supper.” Another lithograph in the series, Gott Strafe England (May God Punish England), portrays what seems to be the crucifixion of three Allied soldiers. Though the subject was based on questionable sources, many chose to believe the Germans were capable of such violence.

Among the images focused on alleged inhumane treatment of innocent civilians, The Barricade, one of the five paintings, depicts soldiers with fixed bayonets cowering behind figures stripped naked, while another of the paintings, The Germans Arrive, shows a soldier strangling a young man who has had both hands cut off, as other soldiers watch; in the background women are being attacked near a burning cottage. The Bacchanale contains a graphic representation of two soldiers holding their rifles aloft, the limp bodies of infants impaled on their bayonets. (Rumors of Germans bayoneting babies were rife in the opening months of the fighting and were used to great effect in Allied propaganda.) Other works from the series include Belgian Farmyard, in which a dead woman lies on the ground as a soldier replaces his tunic, having just raped her, and The Cigarette, portraying a dead woman with her left hand nailed to a door and her left breast cut off.

MOST OF THE BRUTALITIES were rumored but not thoroughly substantiated. Not so Bellows’s Village Massacre. It is based on the actual events of August 23, 1914, when hundreds of inhabitants were executed in the town of Dinant, a strategic crossing point on the River Meuse. Under constant fire from French troops across the river from Dinant, the Germans nonetheless believed that civilians in the town were partly responsible for the attacks and by day’s end, they had killed 612 inhabitants, many by firing squad. In Bellows’s painting (also done as a lithograph), men, women, children, and nuns stand weeping and cursing above massacred bodies; the rifles of the German soldiers are barely visible off to the left, and an officer’s sword has just dropped in the command to fire. Bellows’s composition was clearly derived from plate 26 of Goya’s Disasters of War, which shows a similar line of weapons held by unseen perpetrators firing on civilians.

It is not clear why Bellows chose to do the series on the atrocities in Belgium four years after the fact. Even his dealer in New York was surprised at the brutality portrayed, but Bellows said only, “I had to draw them.” In a preface to an exhibition of some of the lithographs in November 1918, Bellows wrote, “In presenting these pictures of the tragedies of war, I wish to disclaim any intention of attacking a race or a people. Guilt is personal, not racial. Against that guilty clique and all its tools, who let loose upon innocence every diabolical device and insane instinct, my hatred goes forth, together with my profound reverence for the victims.”

Peter Harrington, a frequent contributor to MHQ, is curator of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University. He writes and teaches on military art and artists.