At 4 p.m. on September 18, 1891, Oliver Cromwell Gould, son of 10th Maine Infantry veteran John Mead Gould, took a photograph of Antietam’s East Woods, where his father had witnessed momentous events 29 years earlier. Three days later, at 8 a.m., Oliver focused his camera on a nearby 10-acre field that included a prominent mulberry tree. In the far distance, a wooden fence stretched along the old Smoketown Road—the route his father took to battle on September 17, 1862. We know precisely when and where these historic images were taken because of the meticulousness of John Gould, who accompanied his 21-year-old son to Antietam and wrote details about each photograph in pen on the back mounting for each. According to a detailed logbook kept by his father, Oliver Gould took at least two dozen images at Antietam in 1891, including an unknown number of shots of the iconic Dunker Church. Unfortunately, just about all of those images are believed lost to history. One, displayed above, is in the possession of Virginia-based collector Nicholas Picerno, and six more (shown here in the chronological order in which they were taken) surfaced in New Jersey in January 2018. They provide a reverent window into the early, postwar appearance of one of the nation’s most hallowed battlefields.

The discovery of these additional six images has excited Antietam historians, increasingly hopeful that even more “Goulds” might now be found. The photos once belonged to Irving B. Lovell, an uncle of Bill and Marie Trembley, who noted that they had seen them for the first time decades ago. In 2016, four years after Lovell, a World War II veteran, died at age 92, the Trembleys found the package containing the Antietam images in a closet while cleaning out their uncle’s house and small cabin in Eastport, Maine. When, where, and how Lovell—who lived most of his life in New Jersey—acquired the images is unknown, however.

“These images are truly stunning,” said Stephen Recker, author of the 2012 book Rare Images at Antietam and the Photographers Who Took Them. “They offer an early, pristine view of Antietam…that many of us never thought we would see, complete with the voice of a veteran pointing out particulars in a way we usually just dream about.”

Collaborating with Picerno, the world’s leading 10th Maine expert, and preeminent Antietam historian Tom Clemens, Recker pieced together in his book the story of the Gould images, which were taken before the U.S. War Department greatly altered the lay of the land in 1895, when it added avenues for tourists to use to view the battlefield. “While we found the documentation for his 1891 images at Duke University,” Recker noted, “it was those ‘undiscovered’ images that we really wanted to see.”

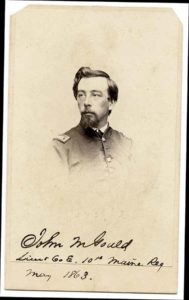

Intelligent and good with numbers, John Mead Gould worked for his father’s bank in Portland before the Civil War. In April 1861, he enlisted in the Portland Light Guards, Company C of the 1st Maine. The regiment served in the defenses of Washington, D.C., returning to Maine to be mustered out in August 1861. That September, Gould reenlisted in the new 10th Maine for two years’ service. Eventually promoted to second lieutenant, he served in the Shenandoah Valley Campaign of early 1862 and saw his first significant action at the August 9, 1862, Battle of Cedar Mountain near Culpeper, Va.

Antietam had by far the most dramatic impact on Gould’s life. It was in the East Woods on the morning of September 17, 1862, that the 22-year-old adjutant was the first to reach a mortally wounded Maj. Gen. Joseph King Fenno Mansfield, who had been shot atop his white horse as he directed troops in his 12th Corps. Gould was among four soldiers to carry Mansfield to the rear.

“Passing still in front of our line and nearer to the enemy, [Mansfield] attempted to ride over the rail fence which separated a lane from the ploughed land where most of our regiment were posted,” Gould wrote to Mansfield’s widow on December 2, 1862. “The horse would not jump it, and the General dismounting led him over. He passed to the rear of the Regimental line, when a gust of wind blew aside his coat, and I discovered that his whole front was covered with blood.”

Antietam was Mansfield’s first and last battlefield command. The 58-year-old officer from Middletown, Conn., died the next morning.

After the war, Gould—who became historian, treasurer, and secretary for a Maine veterans’ group—was especially keen on documenting his regiment’s role at Antietam. Seemingly no detail was too small. For years, he kept up a lively correspondence with veterans on both sides regarding Mansfield’s wounding and death, troop movements, and much more. In the 1890s, he provided hundreds of those letters to the Antietam Battlefield Board, adding significantly to the understanding of the battle. And in 1895 Gould published a pamphlet on Mansfield’s death, noting minute details of the 12th Corps commander’s demise.

Clemens, who edited an authoritative history of the Maryland Campaign by Union veteran Ezra Carman, has high praise for Gould: “He was only interested in the fighting in the East Woods and who killed Mansfield, but wound up getting into a lot more than that. At one point there were six or seven different accounts of where Mansfield was killed, and Gould sorted them out, determining that at least three were people mistaking Colonel William Goodrich of the 60th New York for Mansfield. He really grilled his subjects, asking detailed questions, and his letters, which he routinely shared with Carman, are very helpful for details on fighting in the north end of the field.”

In 1889, John Gould tried to document the battlefield photographically himself. Using the newly developed Kodak camera, among the first deemed simple enough for amateurs to use, he spent a few days taking photos of the East Woods. He would find the experience both unsatisfying and unproductive. The camera he used was cumbersome and did not even have a viewfinder.

“I got ‘rattled’ & made ‘doubles’ & I forgot to make a note of what I was doing,” he wrote in 1894 to 128th Pennsylvania veteran Frederick Yeager. “So when I got my pictures from the printer I couldn’t identify many of them. In truth the visit of 1889 was little more than an aggravation, but it resulted in determining me to go again…”

Thankfully John Gould was diligent in his documentation when he and Oliver returned to the battlefield in 1891. The captions of the six photos shown below are taken verbatim from what Gould penned on the back-mounting of each. The care he took in doing everything possible to set the record straight has greatly enhanced our comprehension of that fateful day.

John Banks, a frequent America’s Civil War contributor based in Nashville, Tenn., is the author of Connecticut Yankees at Antietam and Hidden History of Connecticut Union Soldiers.

The Record Keepers

Nicholas Picerno

Preeminent 10th and 29th Maine collector I hold here image #33. I wonder what John Mead Gould was thinking on September 18, 1891, as he was photographed by his son Oliver standing in the East Woods. This was a very special place for John. Was he transported back to the early morning of September 17, 1862, when his regiment went into action? A prolific chronicler of the 10th Maine Infantry’s exploits, he had an intense interest in the regiment’s history. After the war, he conducted an exhaustive study to determine which Confederate regiment the 10th Maine met on the battlefield. He was also determined to prove that Maj. Gen. Joseph K.F. Mansfield received his mortal wound in the East Woods while leading the 10th Maine and not some other regiment. Gould wrote: “It was bad enough and sad enough that General Mansfield should be mortally wounded once, but to be wounded six, seven, or eight times in as many locations is too much of a story to let stand unchallenged.”

Stephen Recker

Author, Rare Images of Antietam Image #49 is my favorite of the six Gould photos that surfaced in 2018. It is the quintessential image of the golden era of Antietam battlefield photography—after 1888 when George Eastman made dry, flexible photographic film accessible to the masses, and before 1895 when the War Department laid out avenues that forever altered the historic viewsheds. The “ten-acre corn-field,” or the “little corn field,” in this Gould image was never on my radar. It is now bisected by postwar Mansfield Avenue, but in this beautifully photographed and meticulously annotated gem, I travel back to an unforgettable scene, lost to time. The images are a photo historian’s dream come true.

Tom Clemens

President, Save Historic Antietam Foundation, and Editor, The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vols. 1–3 Having worked with John M. Gould’s papers for years, I was aware of his dogged pursuit of any information regarding the East Woods at Antietam and his beloved 10th Maine Infantry. His effort to document exactly where General Joseph K.F. Mansfield was mortally wounded was extremely useful when I wrote a monograph of him for a book a few years ago. The faded ink in Gould’s handwriting pasted on the back of the photograph

evokes memories of the hundreds of times I had seen his familiar scrawl as he quizzed veterans on their memories of Antietam. Holding this photograph (#62), which shows the location of his regiment and the exact spot where Mansfield was shot, is a thrill I will never forget.