“Jump off and scatter! Every man for himself!”

George Wilson, Perry Shadrack, and the 16 other Union men hiding in the locomotive boxcar recognized the voice as that of James Andrews, the civilian spy who commanded the clandestine mission they had volunteered for a few days prior. Each of them knew what jumping meant; trapped behind enemy lines in northern Georgia, escape back to Union forces in Tennessee would be almost impossible given that they had no maps of the surrounding terrain, and would be hunted by Confederate personnel on the train that was fast closing in on them.

However, with their stolen locomotive, the General, running out of steam, remaining on board would surely seal their fate. As grim as the odds were, bailing out was the best option left—six hours and 90 miles after hijacking the train near Marietta, GA. Within seconds, Wilson, Shadrack, and the others leaped from the General, scattering as quickly as possible into the surrounding wood line.

In many respects, the story of the Medal of Honor, America’s highest award for combat heroism, begins with these men. They were the heroes behind the legendary “Great Locomotive Chase”; the first combat action which resulted in the creation of the Medal of Honor. However, although Wilson and Shadrack were eligible for the Medal and performed the same acts of heroism as the 19 other recipients from this bold yet failed mission, the two men have yet to receive the Medal of Honor, despite years of effort to correct this injustice by descendants, active duty military personnel, members of Congress, and other patriotic Americans.

In the spring of 1862, plans were under way for the Union Army to capture Chattanooga, TN. Although the city’s population was approximately only 5,000 people, the town was strategically important to the Confederates because two rail lines intersected there. Over two-thirds of all American railroad lines were laid in the North, therefore, any stretch of Southern track was at a premium for the Confederate army.

Against this backdrop, James Andrews, a civilian spy for the Union, devised a daring, unconventional plan: to steal a Confederate train and drive it through northern Georgia, destroying railroad track, burning bridges, and cutting telegraph wires before returning to Union lines near Chattanooga. The goal was to isolate Chattanooga as a prelude to Union forces attacking and seizing the town. In April 1862, while Brigadier General Ormsby Mitchel and his division of Ohio Soldiers were encamped near Shelbyville, TN., Andrews approached Mitchel and sold him on the plan. Before long, Union commanders covertly asked for one volunteer from each company of Joshua Sill’s brigade. None of the men were provided details of the top secret operation. Wilson and Shadrack were among the volunteers, whose numbers would swell to 22 soldiers and two civilians.

Shortly after nightfall Andrews rendezvoused with his team, who had changed into civilian clothes, in the woods a mile outside of Shelbyville. He briefed them on the mission, emphasizing that capture likely meant execution as spies. When Wilson, Shadrack, and the others were given the chance to back out, none did so. With that, the Andrews Raiders set out for Chattanooga, traveling in smaller groups to avoid arousing enemy suspicion.

They traveled under the guise of being Kentuckians heading south to join the Confederate Army. Despite no prior espionage training, they were able to traverse 100 miles in enemy territory in only three days despite storms, mountains, enemy soldiers, and hostile civilians.

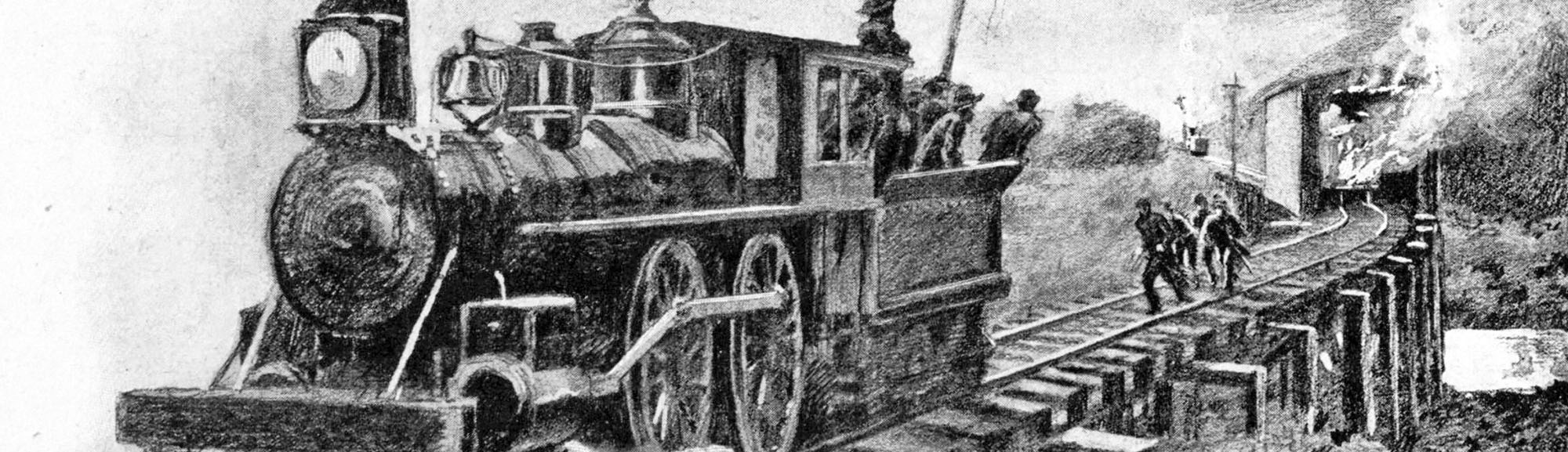

The raiders met up in Chattanooga where they purchased train tickets to Marietta, GA. From there, the men secured lodging before rousing early on the morning of April 12, 1862 for a final review of their plan. At the train station, they boarded the train named General and began their ride north. When the General stopped eight miles later at Big Shanty, the Raiders made their move. Despite thousands of Confederate soldiers encamped within view, the Union men calmly uncoupled the locomotive, tender, and three empty boxcars from the rest of the train. William Knight, who had experience operating locomotives, manned the General while Wilson, Shadrack, and the others hid themselves in one of the empty boxcars. Finally, Andrews whispered, “Let us go now, boys,” and minutes later, Knight shot the General away from Big Shanty, much to the surprise of the Confederate soldiers and civilians around them.

The raiders dashed north towards Chattanooga, all the while severing Confederate lines of communication. Believing that the greatest moment of danger was the engine heist itself, the men breathed a collective sigh of relief, convinced that the remainder of their mission would proceed smoothly until they returned to the safety of Union forces in Tennessee.

Due to this belief, they advanced with caution to avoid arousing suspicion among the Southerners they would encounter. As such, the men kept the speed of the locomotive down to that of a normal passenger train, and had a cover story ready as to why they had to proceed through subsequent stations without delay.

Unfortunately for Wilson, Shadrack, and their comrades, the mission would soon unravel.

The Rebels were in pursuit from Big Shanty. After setting off on foot and later securing a crude rail car they pushed with their feet, the Southerners eventually secured another locomotive further north along the line and gave chase. While the pursuers closed in, the Yankees were still stopping to cut wire and destroy track. Furthermore, they faced an hour delay at one station when they were directed to let a southbound train pass. Recent rainfall also prevented the men from burning bridges after crossing them. These factors collectively disrupted the raiders’ plan and gave the Southerners’ the chance to catch them before Andrews and his men could return the General behind Union lines in Tennessee.

As a result, the Confederates soon closed the distance of the two trains to within rifle range. Realizing the danger, Andrews and his men opened up to maximum speed. The “Great Locomotive Chase” was on.

The Northerners, however, were unable to resupply wood sufficient to keep the fires hot in the General. Wilson, Shadrack, and others in the boxcar threw onto the track anything that would act as an obstacle, all the while giving Andrews and Knight whatever combustible materials they could get their hands on. In spite of these efforts, the stolen engine began to lose steam. Ninety miles and six hours after blazing out of Big Shanty, the raiders abandoned the General and scattered into the woods some 15 miles short of Chattanooga. Wilson, Shadrack, and their fellow raiders were all captured within a few days.

In the weeks to come, the raiders were moved around the South to different jails. After their initial imprisonment in Chattanooga, the raiders were relocated to Atlanta before being transferred back to Chattanooga. Upon their return, they were separated into two groups, with 12 men (including Wilson and Shadrack) being transferred to Knoxville, TN. All throughout, the men endured the hostility of Southern civilians as well as abysmal living conditions, marked by torture, scant food, and cells plagued by vermin and stifling heat. In Chattanooga, they were housed in a cell so grossly undersized that the only way for the raiders to fit was to “spoon” each other while shackled together. Nicknamed by the raid’s survivors as the “hell hole,” the memory of it would come to haunt them in the years following.

On May 31, 1862, the raiders’ worst nightmare started to be realized when Confederate authorities sentenced James Andrews to death without a trial. A week later, he hung from the gallows. The rest of the men housed in Knoxville were charged for being spies. The men were represented by a local law firm, but the trials were mainly for show. In reality, the guilty verdict was a foregone conclusion.

On May 31, 1862, the raiders’ worst nightmare started to be realized when Confederate authorities sentenced James Andrews to death without a trial. A week later, he hung from the gallows. The rest of the men housed in Knoxville were charged for being spies. The men were represented by a local law firm, but the trials were mainly for show. In reality, the guilty verdict was a foregone conclusion.

The Rebels succeeded in trying Wilson, Shadrack, and five other of the Union men before the proceedings were disrupted by the approach of the Union army. As a result, the raiders in Knoxville were moved to Atlanta, where they were once again reunited with their comrades.

For a brief while, the Ohioans held out hope that they had gained a stay in their executions, but such optimism proved fleeting when on June 18, the seven who had been tried were suddenly informed that they were to be executed immediately. As Wilson, Shadrack, and the five others were led off to the gallows, they passed off trinkets and other personal effects in the hope that their fellow raiders would eventually return the items to their families. Although heroic men made up the Andrews Raiders, they wept as they said their final good-byes to their condemned friends.

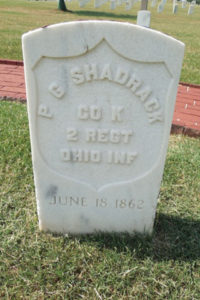

On the day of the execution, Rebel guards argued for the honor of being the hang-man. Surrounded by jeering crowds, Perry Shadrack, George Wilson, and their five brothers-in-arms died from at the end of a rope in Atlanta on 18 June, 1862.

The deaths of Wilson, Shadrack, and their six comrades, fortunately, would be the last executions to take place, partly due to indecisiveness among the Rebel leadership as to if the trials should resume. During that time, eight of the Raiders escaped shortly after the hangings and returned to Union lines and negotiations between the North and South on including the Raiders in a prisoner exchange was successful. The survivors’ ordeal was far from over, though. In the months to come, they were moved between various Southern prisons, experiencing the deprivations of Civil War prisoner of war camps. The six remaining prisoners were eventually released in a prisoner exchange in the spring of 1863. When Secretary of War Edwin Stanton summoned them to the War Department on 25 March, 1863, he was so moved by their account of the ordeal that he presented them with the first Medals of Honor in recognition of their bravery and sacrifices for the Union. It is for this reason that National Medal of Honor Day is celebrated annually on the 25 of March.

Wilson and Shadrack were eventually laid to rest in Chattanooga National Cemetery, alongside the other six Raiders who were also executed in Atlanta. In the years to come, more Medals of Honor would be presented to members of the “Great Locomotive Chase,” to include personnel who escaped from Confederate captivity and found their way back to Union lines, as well as some of the men who died in Atlanta with Wilson and Shadrack.

Wilson and Shadrack were eventually laid to rest in Chattanooga National Cemetery, alongside the other six Raiders who were also executed in Atlanta. In the years to come, more Medals of Honor would be presented to members of the “Great Locomotive Chase,” to include personnel who escaped from Confederate captivity and found their way back to Union lines, as well as some of the men who died in Atlanta with Wilson and Shadrack.

However, for reasons that have been lost to history, Wilson and Shadrack have never received our nation’s highest award for combat heroism, and this injustice continues to the present day in spite of efforts to correct it by descendants, military personnel, members of Congress and their staffers, and other concerned citizens.

Of the 24 men who participated in the mission, 19 have received the Medal. In addition to Wilson and Shadrack, these non-recipients include civilians James Andrews and William Campbell, who were ineligible because the Medal’s regulations at the time limited its presentation only to military members. Additionally, Sam Llewellyn of the 10th Ohio Infantry Regiment turned it down because he felt he did not deserve it since he failed to reach the rendezvous point in Marietta on time and thus was not part of the theft of the General.

Wilson and Shadrack’s unrecognized valor has not completely escaped notice, as evidenced by Sections 564 and 565 of the 2008 Department of Defense Authorization Bill, which “authorized and requested” that the President award the Medal to Wilson and Shadrack. However, even though 2008 was over eight years ago, the Pentagon has not completed this action.

As we approach the 155th anniversary of Wilson and Shadrack’s deaths, one can only hope that the nation they gave their lives to defend will finally bestow upon them the recognition they have waited far too long to receive.

Andrew J. DeKever is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army who hails from Mishawaka, Indiana. He chronicled the “Great Locomotive Chase” in his book, Here Rests in Honored Glory – Life Stories of Our Country’s Medal of Honor Recipients.