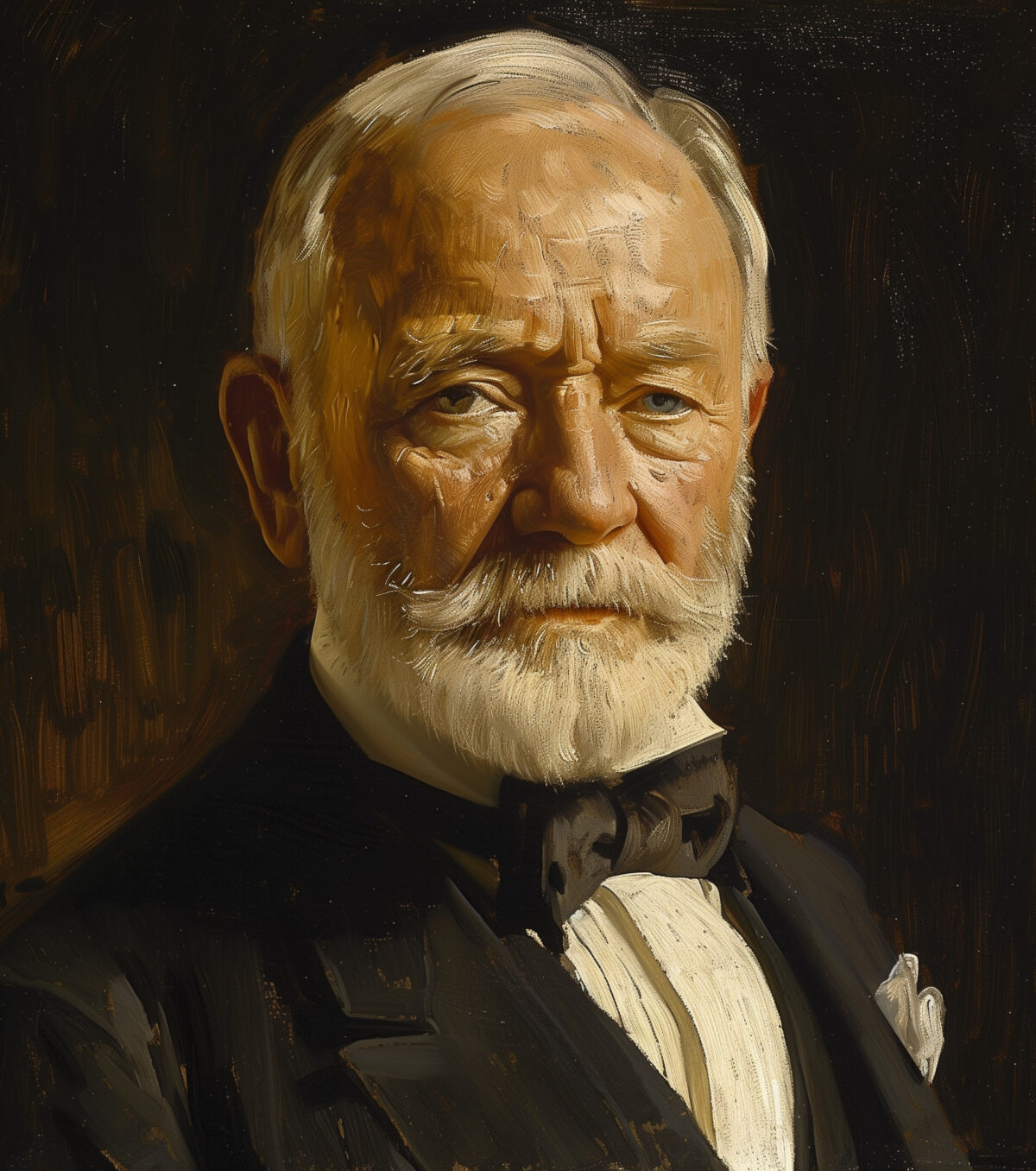

Author and historian David Nasaw, who specializes in early 20th-century American social and cultural history, is a professor of history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. His books Andrew Carnegie (2006) and The Patriarch: The Remarkable Life and Turbulent Times of Joseph P. Kennedy (2012) were nominated for the Pulitzer Prize.

How did a tough businessman like Andrew Carnegie become a pacifist?

He read a lot of philosopher Herbert Spencer, which convinced him that through evolution progress was inevitable. Carnegie had lived through the Civil War as a civilian. He recognized that in war there are no winners, only losers. He saw war as backward, barbaric, outmoded. There had to be a better way to settle disputes between nations—which, for Carnegie, was arbitration. Carnegie pledged himself to hasten war’s extinction.

What inclined him to this point of view?

He was as committed to ending war as he had been to making a profit. He often said that he worked harder after his retirement from the steel business than he had as an industrialist. I don’t think Carnegie’s anti-war sentiments had much to do with his Scottish Calvinist upbringing. And I don’t think it fair to say he was just a tycoon who embraced an admirable cause.

Who else influenced Carnegie, and what were some of his pacifist ideas?

Until Carnegie, the international peace movement was the province of Quakers and international lawyers. Carnegie brought pacifism into the mainstream through articles, speeches, pamphlets, and conferences he sponsored at, among other venues, Carnegie Hall. The major impetus for a revitalized peace movement may have been the Spanish-American War, notably the American invasion and occupation of the Philippines. For people like Carnegie, Mark Twain, William James, and others, the United States was abandoning its principles and donning the mantle of European imperialism in occupying the Philippines with troops who engaged in torture and deprived a people of their independence.

What was Carnegie’s relationship with Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft?

Theodore Roosevelt held Carnegie in contempt. He abhorred Carnegie’s self-righteousness, his unquestioned belief that war was inhumane and wrong. Roosevelt refrained from publicly criticizing Carnegie because he needed the industrialist. Republican businessmen assailed TR as a radical for his trust-busting. The principal industrialist who stood by him was Carnegie, who was admired for his philanthropy. So TR played a double game: in public he feigned friendship and praised Carnegie but in private ridiculed him and opposed his ideas for international arbitration and a world court.

Roosevelt played Carnegie?

Yes. After he left the White House, Roosevelt wanted to hunt in Africa. To pay for that expedition, he accepted Carnegie’s donations. In exchange, Carnegie asked TR to broker a peace between the cousins who ruled Germany and Great Britain—Kaiser Wilhelm and King Edward VII. TR agreed, then sabotaged the initiative when he told the kaiser he stood firm in his judgment that war was sometimes necessary, and that no leader should embrace pacifism. When Edward VII died, the peace plan was scuttled for lack of a partner to work with Wilhelm.

How about Taft?

Taft was part of the Republican establishment that did not want to alienate Carnegie, a Republican and a donor. Taft admired Carnegie but had little need of him. He invited Carnegie to the White House and listened to him. And Taft worked to get the Senate to agree to treaties binding the United States to arbitrate its differences with selected European nations rather go to war. Those treaties never were ratified.

Carnegie refused to give up.

He was a utopian, a visionary. He was not naïve, but he also knew that he’d succeeded at everything he had put his mind to; why not international diplomacy? He believed the world was moving away from the barbarism of war and toward greater civilization. It was not absurd to think that the 20th century would be a century of peace through arbitration.

Should Carnegie have taken his case to the people?

Carnegie was no populist. He believed, with Spencer, that the “fittest” should and would not only survive but would prosper and lead. And remember: he lived a century ago, when kings, queens, and emperors were alive and well in Europe. Carnegie reached out not to the masses, but to university students, because he believed they were the leaders of tomorrow. He was an adherent of the “great man” theory—that the Roosevelts, the Gladstones, the Carnegies, the emperors and kings, made history.

The Great War devastated him.

He was broken by the war and more by national leaders’ enthusiasm and that of the young men following them into war. He hoped President Woodrow Wilson might broker a settlement—he urged Wilson to do so—but when this failed, he retreated into himself. We would say that he had a nervous breakdown. He stopped reading newspapers, ceased writing to dear friends in England, including Liberal Party statesman John Morley, to whom he had corresponded every Sunday for decades. He saw no visitors, stopped talking to his wife and daughter. Only when a truce was signed did he rouse himself, write President Wilson a congratulatory note, offer best wishes on Wilson’s plan for a League of Nations, and propose his Peace Palace at The Hague as a venue for a peace conference.

Was Carnegie’s $25 million-plus outlay for the cause money well spent?

His palaces of peace, certainly at The Hague, are living monuments to his dream. So, too, the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Have these institutions brought peace on earth? Of course not. But have they kept alive a dream; have they contributed to the promotion of peace? I think so.

What’s the lesson in Carnegie’s crusade?

He was very much a “fool for peace.” His legacy is the notion that civilized people should not consider war inevitable but, rather, an aberration to be abolished. He was a “possibilist,” not a realist. We need more such men, men willing to dream of a better world and to do what they can to bridge the gap between the present and that better future they envision. Andrew Carnegie’s dreams of a world without war are as relevant today, perhaps more so, than they were a century ago.