It was a chilling sight. Thirteen men in sullied Union Army uniforms lined up on a scaffold, rough corn sacks over their heads, a noose around each one’s neck. A young lieutenant produced the execution order and read it as loudly as he could to the brigades of Confederate infantrymen formed in a huge square around the gallows. After that attempt to justify the impending doom of the condemned, a signal was given. The flooring of the gallows collapsed, simultaneously dropping the entire long row of faceless figures. The hooded victims dangled, jerked and died, their lifeless bodies suspended in midair. A captain of the 8th Georgia Cavalry remembered that it ‘was an awful cold, bad day and the sight was an awful one to behold.’

Many of the townspeople of Kinston, N.C., had left their usual activities that day, February 15, 1864, to observe the proceedings. Such grim military rituals had almost become a routine part of their existence. Two Federal soldiers had already been hanged at the same location by troops under Confederate Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett, the flamboyant Virginian who led the climactic charge against Cemetery Ridge on the third day at Gettysburg. Seven more would follow in a few days, but this was the largest group to be dispatched at one time.

All of the hanged Union soldiers and those still to climb the gallows steps had been captured by the Rebels during an abortive Confederate operation against New Berne, 32 miles to the southeast. The Federals had held the town since March 1862, when Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside had captured New Berne as part of his operations along the North Carolina coast. The loss of any of its ports hurt the Confederacy, and Pickett hoped to recapture the town by a three-pronged attack of about 13,000 men.

Brigadier General Seth Barton’s column of artillery, cavalry and infantry was to move on New Berne from the southwest, while Colonel James Dearing, with a smaller number of cavalrymen, infantrymen and guns, drove on the city from the northeast. Pickett accompanied the division of Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke as it pushed on New Berne from the northwest. The elaborate plan also called for Confederate warships to sail up the Neuse River, which flowed north of the town, in support of the attacks. The complex operation started well, but ultimately failed due to the strong Yankee forts and earthworks that surrounded New Berne. Pickett was irate. He had already been involved in one failed assault, and now his name was associated with another.

Although the Confederates had not recaptured New Berne, their assaults had snagged between 300 and 500 Northern prisoners, many taken by Hoke’s soldiers when they overran a blockhouse. For some of the captives ‘Northern’ had several connotations, for they were natives of the Old North State. In fact, many North Carolinians fought for the Union. Three Federal regiments composed of Tar Heels were raised during the war, while more than 10,000 North Carolinians fought for the Union in units raised by other states. Being a blue-coated North Carolinian captured by fellow Tar Heels in gray was not akin to an automatic death sentence. But the prisoners taken by Pickett’s men at New Berne had an additional twist to their story, for they were accused of switching sides — serving in the Confederate Army, then deserting and fighting for the Northern cause.

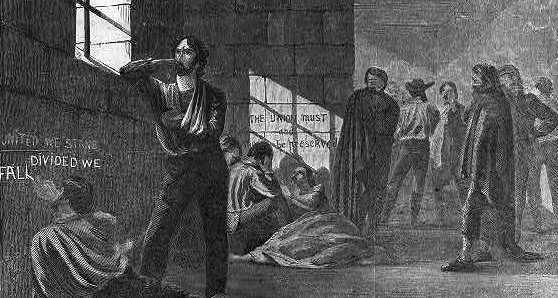

The Confederate authorities’ contempt for the soldiers who had left their army’s ranks was demonstrated from the moment of their capture. When the failed expedition against New Berne returned to Kinston, the prisoners were initially herded into the Lenoir County Court House and later transferred to the nearby Old Kinston Jail, where most were forced into a large, barren dungeon.

Elizabeth Jones, whose husband Stephen was one of the prisoners, said, ‘I carried bedding to him myself to keep him from lying on the floor.’ The men had to subsist on one cracker a day until relatives brought them additional food.

Some of the prisoners had formerly served in the 10th North Carolina Artillery and were recognized by one of their former officers. They were pointed out to Pickett, who berated them. ‘What are you doing here? Where have you been?’ he questioned, continuing: ‘God damn you, I reckon you will hardly ever go back there again, you damned rascals. I’ll have you shot, and all other damned rascals who desert.’

Fifty-seven of the other prisoners had served the Confederacy in the 8th Battalion Partisan Rangers, also known as Lt. Col. John H. Nethercutt’s battalion. Formed in the spring of 1863, the home guard unit rode patrols, conducted guard duty in the New Berne region and received its orders from authorities in the Neuse River town. When the battalion was incorporated into the 66th North Carolina Infantry Regiment in October, several hundred of Nethercutt’s men, unwilling to be placed under control of the Confederate government, deserted. The Federals who had once served with Nethercutt were mostly poor, illiterate farmers with no political or economic interest in the war that had disrupted their lives.

Those accused of serving the North faced certain execution. No official records of courts-martial of the prisoners have been found, but contemporary newspaper reports claimed that their fates were sealed in hastily convened military courts. At least some of the men evidently did go through a trial process, but it was more of a kangaroo court that a formal court-martial. It is also possible that some of the men were executed without any type of trial. To make their crime appear even more heinous, the decision was made to hang the turncoats, rather than have them face a firing squad, which was the normal punishment for deserters.

One man among the group, had he been granted the opportunity to summon witnesses and not been forced to sit before a kangaroo court, was in a position to present far stronger justification for his actions. Twenty-five-year-old Charles Cuthrell of Broad Grove, N.C., had resisted serving in the Confederate Army and was hanged apparently for simply maintaining his loyalty to the U.S. government. After the war, three of Cuthrell’s neighbors attested that in January 1862 Confederate authorities had notified men fit for military duty that if they did not come forward and enlist they would be conscripted into the Rebel army. Cuthrell was one of those who was drafted and, in fact, had to be taken by force from his home.

Cuthrell ended up at a ‘Camp of Instruction’ at New Berne and was placed in Captain Alexander C. Latham’s Battery, 3rd North Carolina Artillery. A family friend recalled that Charles insisted, as did his father and four brothers, that they were Union men and ‘that if compelled to go into the Rebel service against his will, he would be of no service to the Confederacy, from the fact that he would not fire upon the flag of his Country, or any of its defenders.’

Cuthrell remained in Confederate service only two months. During the March 1862 Battle of New Berne, the only engagement in which he was present, his neighbors remembered that Cuthrell ‘made good his previous intentions as before stated publicly, in refusing to fire upon his country’s flag’ and ’embraced the first opportunity offered for escape & entered the Union lines.’

During the subsequent Union occupation of the town, the 2nd North Carolina (U.S.) was formed. Cuthrell stepped forward and made his mark on an enlistment form on December 22, 1863, and swore that he would ‘bear truew faith and allegiance to the United States of America and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whomsoever….’ Less than two months later he would be captured by Pickett’s men, tried and executed for his Unionist stand in a seceded state.

After Cuthrell and the other men hanged on February 15 were cut down from the gallows, they were stripped of their blue uniforms, which were given to the civilian hangman — a strange, cross-eyed, nameless man from Raleigh — as he had demanded the garments as part of his pay for accomplishing the feat of mass execution. Georgia Corporal Sidney J. Richardson wrote his folks: ‘Oh! I fergotton to tell you I saw…Yankees hung to day, they deserted our army and jyned the Yankey army and our men taken them prisoners they was North Carolinians. I did not maned [mind] to see them hung.’

The bodies, some totally naked, were left lying by the scaffold until claimed by relatives, who had to provide their own transportation to carry their men back to their family burial plots. The army would not provide any of its wagons. Those not claimed by kin were simply interred in the sandy field by the gallows. It is likely that Charles Cuthrell was one of those buried in that fashion because he lived more than 30 miles away, and it is doubtful his 19-year-old wife, Celia Serle Cuthrell, could have traveled that distance to recover his remains even if she was aware of his hanging. The couple had also recently suffered the loss of an infant.

A few days after the 13 were put to death, another set of hangings took place in Kinston, as well as a number of shootings of Confederate deserters who had been rounded up in the area but who had not gone over to the Federals. So many executions were taking place, in fact, that one Confederate officer would later write in disgust: ‘Sherman had correctly said that war is hell, and it really looked it, with all those men being hung and shot, as if hell had broke loose in North Carolina.’

The Rev. John Paris, chaplain of the 54th North Carolina Infantry, was also struck by the enormity of the executions. He had attended the men before they took their final steps to the gallows and recalled: ‘The scene beggars all description. Some of them were comparatively young men; but they had made the fatal mistake; they had only 24 hours to live, and but little preparation had been made for death. Here was a wife to say farewell to a husband forever. Here a mother to take a last look at her ruined son; and then a sister who had come to embrace, for the last time, the brother who had brought disgrace upon the very name she bore by his treason to his country.’

Word of the executions spread throughout the North by way of newspaper accounts. The New York Times considered the hangings ‘Cold Blooded Murder.’ The outraged Union officers who had enlisted the executed Southerners vociferously called for action against those responsible. The protests of one Union general actually may have unwittingly helped the Confederates carry out the hangings.

Before the executions had begun, Maj. Gen. John Peck, the Union commander of the District of North Carolina, wrote Pickett to demand that the soldiers captured from the 2nd North Carolina (U.S.) be treated properly, and included a list of their names. Pickett wrote back a sneering letter thanking Peck for providing the list that would help in ferreting out those who might have previously served the Confederacy.

A thorough investigation of the entire affair, however, could not be conducted by the North until the war ended the following year. In October 1865, Maj. Gen. Thomas H. Ruger, commander of the Department of North Carolina, ordered the establishment of a board of inquiry to investigate the matter. From October to November the officers on the board questioned 28 witnesses about the hangings, including numerous townspeople, widows of the deceased and ex-Confederate officers in Kinston and New Berne.

The board of inquiry concluded that Pickett, who ordered the courts-martial of the men and approved the sentences, and Hoke, who was responsible for carrying out the executions, had ‘violated the rules of war and every principle of humanity, and are guilty of crimes too heinous to be excused by the United States government and, therefore, that there should be a military commission immediately appointed for the trial of these men, and to inflict upon the perpetrators of such crimes their just punishment.’

As a preliminary step to those punishments, Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt recommended to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton on December 30, 1865, that ‘Pickett be at once arrested and held to await trial.’ But even if they had wanted to take Pickett into custody for his actions against the North Carolinians, there was no way of getting their hands on the West Point-trained former U.S. Army captain. Having been tipped off by some old army friends of what was contemplated against him, Pickett had fled Virginia to Montreal, Canada, where he was living in a rooming house with his wife and baby under the assumed surname of Edwards. He had even taken the precaution of having his distinctive long, curly hair shorn short to avoid recognition.

There Pickett remained until Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the commanding general of the Army and an old friend of Pickett’s from prewar days in the Regular Army, provided him with a special pass protecting him from arrest. Pickett had written his former opponent asking for the favor. Later Grant would intercede with President Andrew Johnson to extend Pickett a full pardon for his Kinston actions. In his appeal to Johnson, Grant stated that ‘General Pickett I know personally to be an honorable man, but in this case his judgment prompted him to do what cannot well be sustained.’ He added, however, ‘I do not see how good, either to the friends of the deceased, or by fixing an example for the future, can be secured by his trial now.’

Doing so, Grant argued, would open up the question of whether the government was disregarding its contract entered into in order to secure the surrender of an armed enemy. After all, the terms Grant offered General Robert E. Lee at Appomattox said nothing about bringing George Pickett to trial as a war criminal. On Christmas Day 1868, outgoing President Johnson issued a general amnesty that got Pickett off the hook permanently for the Kinston hangings.

After the war, Charles Cuthrell’s destitute wife, Celia, sought compensation for her loss and found herself having to establish the validity of Charles’ Union Army service and the circumstances of his brief Confederate Army association to qualify for a widow’s pension from the U.S. government.

The adjutant general’s office in Washington provided her with a document attesting to the fact that Cuthrell was reported ‘murdered by order rebel Genl’s Pickett & Hoke at Kinston, N.C., in the Spring of 1864.’ Five different Craven County neighbors provided her with sworn affidavits attesting to Cuthrell’s outspoken Union sentiments and his conscription into Confederate service. Eventually she became eligible for Widow’s Pension No. 151963.

Two other widows, those of Lewis Freeman and Jesse Summerlin, also were able to make a case for an $8-a-month pension by establishing that their men had been coerced into joining the Confederate ranks. Both men had deserted their Rebel home guard unit. ‘My husband was a Union man and kept out of the war as long as he could with safety to himself but he finally enlisted in a company of Confederate troops,’ stated Freeman’s widow, who was left with six children to raise. ‘I think he was induced to enlist from fear of bodily harm.’

The pittances extended to the poor widows brought only further resentment from pro-Confederates within politically divided North Carolina. For those who remained loyal to the Southern cause, serving in the Union Army, no matter under what circumstances, amounted to disloyalty. The motivation of the men executed had varied from fear to patriotism. For Charles Cuthrell of Broad Grove, N.C., following his conviction to remain loyal to the United States cost him his life — not from disease or on the battlefield like most Northern soldiers, but from the hard bite of the hangman’s noose.

This article was written by Gerard A. Patterson and originally appeared in the November 2002 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!