Royal Air Force fighter pilots, including a group of American volunteers, paid a heavy price during their brave defense of the strategic archipelago.

On March 21, 1942, Pilot Officer Howard Coffin, an American from Los Angeles and a volunteer in the Royal Air Force, sat down to record the day’s events in his diary. He had been flying Hawker Hurricanes in defense of Malta for six months. “Our hotel was bombed,” he wrote. “P/O Streets, the third of the four Americans to go, P/O Hallett, F/L Baker, F/L Waterfield, P/O Guerin, P/O Booth, lost their lives. This day will never be forgotten….Four ships sunk in the harbor. Hospitals bombed, churches and town after town cleaned out. What a slaughter of human lives. Unless help comes soon, God save us. No food, cigarettes, fuel. They are doing a lot of evacuating of English wives.”

Malta, just 17½ miles by 8¼, is the largest of several islands forming an archipelago in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, south of Sicily and almost equidistant from Gibraltar in the western approaches and Alexandria, Egypt, in the east. An outpost of the British empire since the early 19th century, Malta was especially important during World War II, providing British naval and aircraft units with a base from which to strike at Axis supply routes between Italy and North Africa.

On June 11, 1940, the day after Italy declared war on Britain and France, the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force) commenced operations against Malta. Shortly before 0700 hours, Macchi C.200 fighters escorted a group of Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 bombers across the 60 miles of sea separating the archipelago from Sicily. British anti-aircraft guns engaged the Italians while Malta’s Fighter Flight scrambled Gloster Sea Gladiators. It was the first of countless actions that would continue for 2½ years, as the Italians, later aided by their German allies, attempted to neutralize and seize the island.

Initially, Fighter Flight’s outdated biplanes were Malta’s sole aerial defense. They would soon be immortalized as Faith, Hope and Charity (although there were at least four aircraft on strength). The Gladiators were joined on June 21 by two Hurricanes, which were retained after landing on Malta while en route to the Middle East. The following day, six more in-transit Hurricanes arrived, three of which were reallocated to Fighter Flight. But it took nearly two months before an effort was made to send further reinforcements. On August 2, a dozen Hurricane Mk. Is took off from the aircraft carrier HMS Argus and flew 380 miles across the Mediterranean to Malta. One Hurricane crash-landed at Luqa aerodrome and was written off, but the remainder joined surviving fighters there to form No. 261 Squadron.

Benito Mussolini’s faltering offensive against Malta and the British Mediterranean fleet, together with the North African campaign and Italy’s invasion of Greece, ultimately led Adolf Hitler to come to the aid of his ally. Toward the end of 1940, elements of the Luftwaffe’s X Fliegerkorps (Air Corps) began to arrive in Sicily from Norway. By mid-January 1941, the Luftwaffe had gathered in Sicily a formidable array of aircraft that included Junkers Ju-87s and -88s, Heinkel He-111s and Messerschmitt Me-110s.

The arrival at Malta’s Grand Harbour of the damaged carrier Illustrious in January was followed by days of intense action as the Luftwaffe tried, but failed, to sink the ship at its moorings. The episode is still remembered as the “Illustrious Blitz.” For Malta’s fighter pilots, the worst was yet to come when, in early February, Messerschmitt Me-109Es of the 7th Staffel (Squadron) of Jagdgeschwader (Fighter Wing) 26 were transferred from Germany to Gela, in Sicily. The outstanding squadron commander was Oberleutnant Joachim Müncheberg, a Knight’s Cross recipient with 23 victories. The faster, cannon-armed Me-109E was more than a match for Malta’s Hurricanes, and German tactics were arguably more effective than those of the Royal Air Force. During the next four months, 7/JG.26 would claim at least 42 aerial victories (including two during the unit’s brief involvement in the invasion of Yugoslavia). Twenty were credited to Müncheberg. Incredibly, not one Messerschmitt was lost over Malta.

Squadron Leader Charles Whittingham probably expressed the general feeling among the RAF pilots when he wrote in his diary on May 14: “Another pilot hacked down. The position is getting very serious. The morale of the squadron is naturally very bad. People are being hacked down with no results by 109s—much superior A/C in very large numbers and able to position themselves behind the sun. The Maltese themselves are complaining that it is murder to send them up. But HQ will not give way.”

Malta’s fighter pilots had something of a respite when, in mid-1941, the balance in air power shifted between the opposing sides in the central Mediterranean. For Hitler, the priority in June would be the invasion of Russia. Accordingly, the Luftwaffe redeployed the majority of its aircraft in Sicily. The war in the Western Desert also had to be considered, and so 7/JG.26 was sent south to Libya. For a few months, the RAF would once again have only the Italians to contend with.

Meanwhile, a new Malta unit, 185 Squadron, was raised, and 249 Squadron, en route from Britain to the Middle East, also arrived. Its pilots were informed they were to remain on Malta so that 261 Squadron could be relieved. In June the island was further reinforced with fighter pilots of 46 Squadron, after which the unit was redesignated 126 Squadron. On November 12, 34 Hurricanes flown by pilots of 242 and 605 squadrons arrived from the carriers Argus and Ark Royal. (The next day Ark Royal was sunk by the German submarine U-81.)

With the onset of winter, the Germans reappeared, as aircraft were transferred from Russia and northern Europe, south to Sicily. Soon, II Fliegerkorps took over from the Regia Aeronautica during daylight operations over Malta. German raids, which began on a relatively small scale, increased in intensity toward the end of December, with daylight bomber sorties heavily escorted by the latest Me-109Fs.

By this stage of the battle, Malta’s air force was becoming increasingly cosmopolitan. Initially, fighter pilots were nearly all British officers and senior noncommissioned officers serving in the RAF or Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. Over time, pilots arrived from the Dominions (in particular, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa), Rhodesia and the United States.

The first Luftwaffe bomber to fall on Maltese soil in 1942 was engaged by pilots from several countries. On January 3, two Ju-88s departed Sicily and headed south toward Malta. For Oberleutnant Viktor Schnez and his crew, recently arrived from the Eastern Front, it was their third Mediterranean mission. It would also be their last. After Schnez had carried out their task, Hurricanes and anti-aircraft guns singled out his Junkers. Canadian Sergeant Garth Horricks of 185 Squadron noted in his logbook: “I attacked Ju. 88 from quarter astern and set its port engine on fire. It crashed near Takali. Rear gunner put 10 bullets in my plane. I was hit in left arm.”

Another Hurricane pilot, American Pilot Officer Edward Streets of 126 Squadron, reported: “On patrol as Red One – at about 18,000 ft. Saw one Ju 88 over Luqa – Also 3 or 4 109’s. Attack one (88) immediately after Yellow 2 delivered attack – Followed enemy until all types bailed out firing all the time from ¼ to stern until it spun in and burned up – Followed it down to 0 feet. 250 Rounds of ammunition fired – Return fire from Rear Gunner until he bailed out.”

The German bomber crashed near the town of Żebbuġ. Anti-aircraft fire also downed an Me-109, killing Unteroffizier Werner Mirschinka of 4/JG.53. Among Malta’s fighter pilots, 126 Squadron’s Pilot Officer Howard Coffin was slightly injured when he crash-landed after being shot up by a pair of Messerschmitts.

Coffin had been one of the first Americans to arrive on Malta in September 1941, together with Pilot Officers Edward Steele (reported missing December 19, 1941), Donald Tedford (missing February 24, 1942) and Streets. “Junior” Streets was among the six men lost when their hotel at Mdina was bombed on March 21, 1942. Of the four, only Coffin outlived his time on Malta.

Just three American dead were buried in Maltese cemeteries. Four times as many have no known grave. Among the latter, Pilot Officer James Tew was killed in the early afternoon of March 3, 1942, after Hurricanes of 242 and 605 squadrons scrambled to intercept three Ju-88s and a number of Me-109s. On that occasion, three British fighters were lost. Tew’s Hurricane crashed at Marsaskala Bay, and very little was found of the pilot. Canadian Flight Sergeant David Howe bailed out over land, injuring his ankle, while another Canadian, Sergeant Ray Harvey, bailed out into the sea badly burnt and mortally wounded. He was dead by the time Air-Sea Rescue arrived. It was rumored at the time that he had been shot up after taking to his parachute.

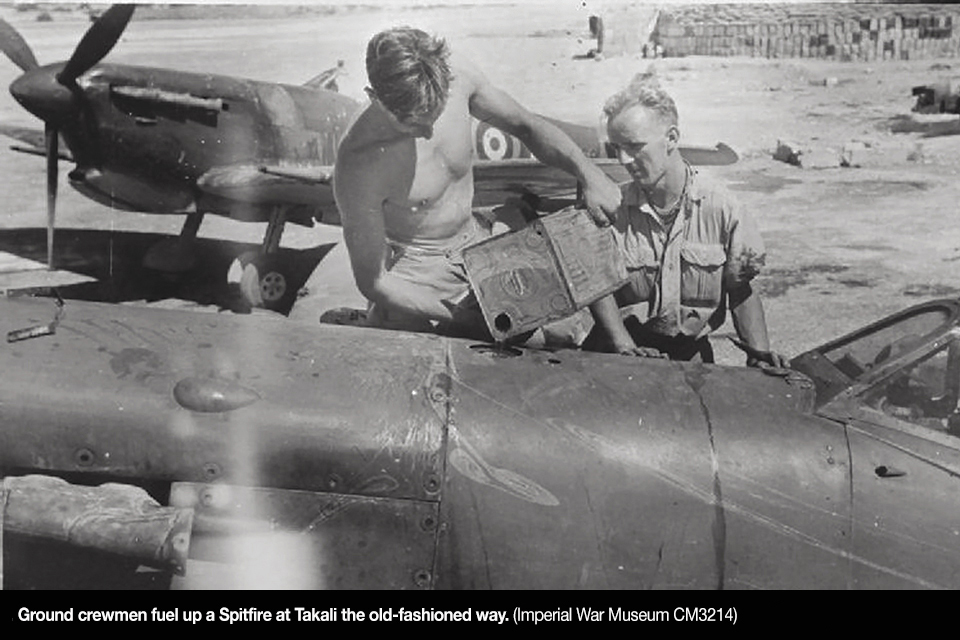

In 1942 the odds were raised in favor of Malta’s defenders when, on March 7, 15 Spitfire Mark Vbs flew in from the carrier HMS Eagle and joined 249 Squadron. Here, at last, was a British fighter with the speed and firepower to match the Me-109. Before the end of the month, Malta was reinforced with 16 more Spitfires. Meanwhile, fighter units underwent some reorganization. Numbers 242 and 605 squadrons were absorbed by 126 and 185 squadrons and, on the 27th, Hurricane IIcs of 229 Squadron were transferred from North Africa to Malta.

The contribution made by the Maltese was formally recognized on April 15, 1942, by King George VI: “To honour her brave people I award the George Cross to the Island Fortress of Malta to bear witness to a heroism and devotion that will long be famous in history.” It was the highest honor that a British sovereign could bestow on a community.

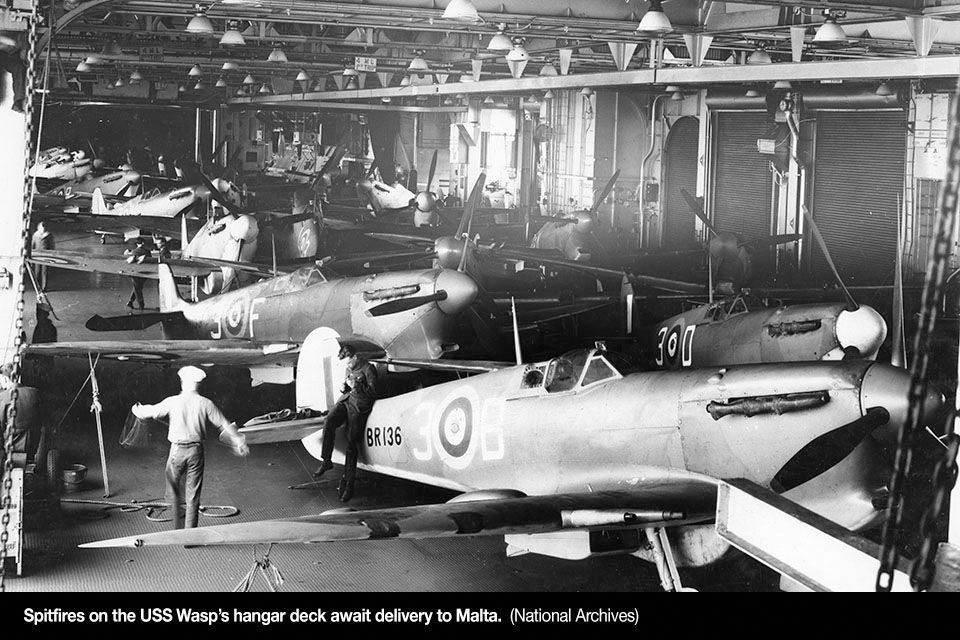

Malta’s ordeal, however, was far from over. Five days later, 47 Spitfires comprising 601 and 603 squadrons flew off the U.S. Navy carrier Wasp. All but one, an American pilot who diverted to North Africa, arrived at Malta. There were three major raids against the island nation the next day. The third attack ended with claims for at least four enemy aircraft destroyed and several probably destroyed and damaged. But Malta’s fighter pilots came off worse. Of five 126 Squadron Spitfires that took to the air, three failed to return. One crashed after the pilot flew too low through a bomb explosion and bailed out. Two fell to Me-109s of JG.53. Flight Sergeant George Ryckman, a Canadian, was reported missing, while American Pilot Officer Hiram Putnam was critically wounded by cannon fire. His Spitfire flew into a steel radio mast before crashing nearby. “Tex” Putnam died of his injuries the next day.

By the end of the month, as other fronts were given priority, preparations were underway to redeploy Luftwaffe units, thereby reducing the number of German bombers and fighters in Sicily. Attacks against Malta would continue, supplemented by additional Italian aircraft.

According to Luftwaffe records, Malta operations between March 20 and April 28, 1942, involved 5,807 sorties by bombers, 5,667 by fighters and 345 by reconnaissance aircraft—a total of 11,819 sorties. In this 5½-week period, the weight of bombs dropped is reported to have exceeded 7,228 tons.

The recent Spitfire deliveries meant that Malta could carry on the fight without Hurricanes. Toward the end of May, therefore, 229 Squadron departed for the Middle East. On June 9, Eagle delivered another 32 Spitfires, nearly all of which landed without mishap. One of the newly arrived pilots was Sergeant George Beurling, a Canadian who was assigned to 249 Squadron. Beurling would become Malta’s top-scoring ace and the most successful of Canada’s fighter pilots. He was “a positive master of air combat and possessed phenomenal skills in deflection gunnery,” according to American Pilot Officer Leo Nomis, who also recalled that of all the fighter pilots in Malta, “The only person I ever met who liked it there was Beurling.”

At the end of June, 601 Squadron departed Malta to join the hard-pressed RAF in North Africa. July began with a renewed Axis offensive against Malta that would continue for the next two weeks.

During a morning raid on July 3, several enemy fighters crossed the coast at high altitude. Twelve Spitfires of 126 Squadron were airborne. Although neither side made any claims, two Spitfires were lost due to mechanical problems. One aircraft came down off the coast: Pilot Officer F.D. Thomas bailed out and was picked up soon afterward. The other Spitfire dived headlong into a field near the town of Siġġiewi, crashing with such force that both of its 20mm Hispano cannons were firmly lodged in bedrock. (Efforts to remove them were unsuccessful, and one cannon, less working parts, and the barrel of the other were left in situ, an unintentional yet impressive monument to the air battle for Malta.) Pilot Officer Richard McHan, an Idaho native, bailed out and landed close to his crashed Spitfire. He was taken to an army medical aid post and treated for his injuries, including a broken ankle and concussion.

That summer, Spitfire deliveries continued, enabling 1435 Flight, previously rendered ineffective as a Hurricane unit, to be re-equipped and retitled 1435 Squadron. But in order to survive, Malta needed a constant resupply of aviation fuel and ammunition, replacement fighters and other essential provisions. On August 3, Operation Pedestal left Scotland on the first stage of its journey to the Mediterranean. Pedestal would result in the delivery of about 32,000 tons of supplies, as well as 37 Spitfires, which were flown off HMS Furious. Of 14 merchant vessels, nine were lost, together with Eagle, two cruisers and one destroyer. Of the five surviving merchantmen, the Texaco oil tanker Ohio came to epitomize the Malta convoys. After being disabled by torpedo and bombing attacks, in which one bomber crashed onto its deck, the battered ship was guided into Grand Harbour lashed between two destroyers and with another secured to the stern as an emergency rudder. The date was August 15, the Feast of the Assumption, known locally as the Feast of Saint Mary. Ever since, the Maltese have referred to Operation Pedestal as Il-Konvoj ta’ Santa Marija.

Only a few American fighter pilots had been posted to Malta in 1941. Forty-two are known to have served there in Spitfire units in 1942. They included Sergeant Claude Weaver from Oklahoma, who was shot down during an offensive sortie over Sicily on September 9, 1942. He chose to force-land on the enemy coast rather than take his chances bailing out over the Mediterranean. Weaver was taken prisoner, but he escaped a year later and returned to Malta before being flown to Britain soon after. On January 28, 1943, while serving in 403 Squadron, he was again shot down and this time fatally injured. Pilot Officer Weaver, DFC, DFM and Bar, is buried at Meharicourt Communal Cemetery in France.

As summer gave way to fall, the battle continued. On October 11, 1942, the Luftwaffe and the Regia Aeronautica launched the first in a series of attacks in a major effort to crush Malta. This, the final Axis onslaught, would continue for a week before the Luftwaffe changed its strategy, replacing daylight bomber sorties with fighter sweeps and fighter-bomber attacks. But now there was hope at last for beleaguered Malta.

Following a successful Allied offensive at El Alamein in Egypt, Anglo-American forces landed in French North Africa on November 8. For Malta, lack of provisions was still an issue, although the situation was alleviated by supply runs undertaken by individual ships and submarines. It was not until November 20 that the siege could be considered as over, with the arrival during Operation Stoneage of four merchantmen: Bantam (Dutch), Denbighshire (British), Mormacmoon (American) and Robin Locksley (American).

Enemy air attacks continued for some time, albeit only sporadically and on a much reduced scale. The cost to both sides had been high, with well over 1,000 aircraft written off and thousands of military personnel and civilians killed and injured. But Malta was never defeated.

In July 1943, two months after the Afrika Korps surrendered in Tunisia, Malta played a prominent role as Allied headquarters and as a forward air base during the Allied invasion of Sicily. Italy capitulated soon afterward, on September 8. Two days later, the Italian naval fleet began to assemble under escort at Malta. It was a fitting tribute to the Maltese and to all who had defended their island.

British author Anthony Rogers specializes in researching and writing about the Mediterranean theater during World War II. His books include the recent Air Battle of Malta, which is recommended for further reading.

This feature appears in the March 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!