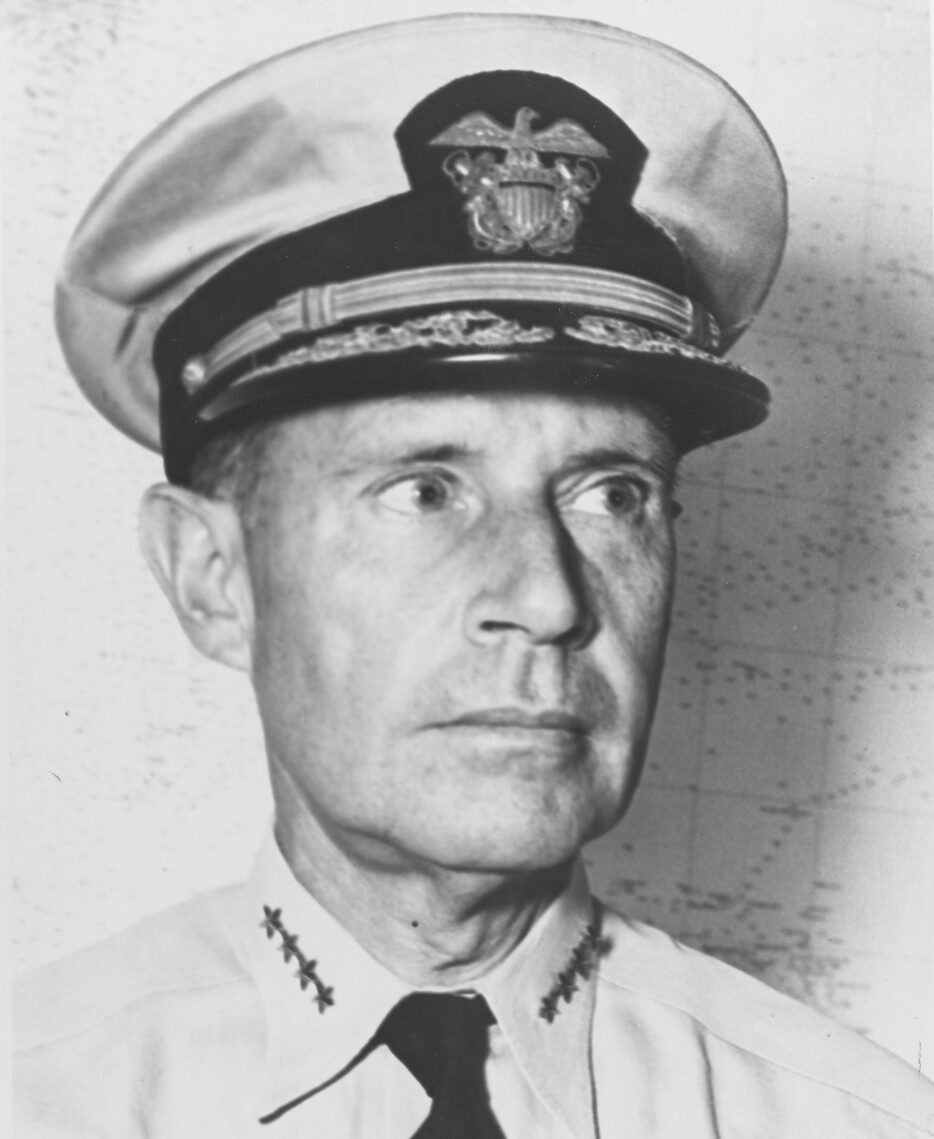

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz called him ‘a fine man, a sterling character, and a great leader, and said, nothing you can say about him would be praise enough. Admiral William L. Calhoun saw him as a cold-blooded fighting fool. Historian Samuel Eliot Morison believed he was one of the greatest fighting and thinking admirals in American naval history.

Yet because of his modest, retiring nature, Spruance was never a popular hero in the manner of Admirals Nimitz, William F. Halsey and Marc A. Mitscher. He disliked personal publicity and had a reputation for freezing reporters who invaded his privacy.

His entry in Who’s Who in America was only three lines long (including his full name), and a footnote in Morison’s monumental history of the U.S. Navy in World War II testifies to his modesty. Morison’s text refers to …Spruance, victor at Midway. In the footnote Morison says, Admiral Spruance, in commenting on the first draft of this volume, requested that I delete ‘victor at’ and substitute ‘who commanded a carrier task force at,’ but…I have let it stand.

Recently promoted to rear admiral, Spruance was assigned to command a division of cruisers in the Pacific under Admiral Nimitz in 1941. He was then 55. He was in this post on June 4, 1942, when the Japanese navy attacked Midway Island in force.

The month before, American and Japanese naval units had fought the Battle of the Coral Sea, and both closely matched sides had suffered. The enemy units were forced to withdraw their battered aircraft carrier Shokaku, while the Americans had to abandon the old, cherished carrier Lexington. The other U.S. flattop, Yorktown, escaped with one bomb hit. The Americans lost 74 carrier planes; the Japanese 80. The U.S. fleet lost fewer men, but it lost a fleet carrier while the Japanese lost only the light carrier Shoho.

But what was important about this action–the first naval battle in history fought by fleets that never came within sight of each other–was that the U.S. Navy had thwarted the enemy’s planned capture of Port Moresby in strategic New Guinea. The Coral Sea fight was virtually a warm-up for the Battle of Midway, regarded later as the turning point of the war in the Pacific.

The Japanese planned to outwit the U.S. forces at Midway. They would draw them north to deal with a Japanese invasion in the bleak Aleutian Islands, and then strike at unprotected Midway.

For the main Midway assault, the Japanese force consisted of the main battle fleet under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, composed of three battleships, a light carrier and a destroyer screen; Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s combined fleet of two battleships, two heavy cruisers, destroyers and four fleet carriers carrying more than 250 aircraft; and an invasion task force led by Admiral Nobutake Kondo, consisting of a dozen transport ships carrying 5,000 troops, closely supported by four heavy cruisers, two battleships and a light carrier; and a three-cordon submarine force intended to neutralize U.S. countermoves. To the Aleutians, the Japanese dispatched an invasion task force of three transports carrying 2,400 troops, supported by two heavy cruisers, a two-carrier support force and a covering group of four battleships.

The battle would open in the mist-shrouded Aleutians with airstrikes against Dutch Harbor on June 3, followed by landings at three points on June 6. The Japanese expected no American ships in the Midway area until after the landing there, and they hoped that the Pacific Fleet would dash northward as soon as it received word of the opening strikes in the Aleutians. If this happened, it would enable the Japanese to pinch the Americans between their two carrier forces.

Spruance was about to face the sternest test in his long, distinguished career. He was drafted on short notice for his date with destiny. When Vice Adm. Bull Halsey was confined to a hospital with a skin disease, Pacific Fleet Commander Nimitz appointed Spruance to succeed him as commander of Task Force 16.

Things did not look hopeful for Spruance and his force on the eve of Midway. The Americans were gravely outnumbered by the lurking enemy armada. Nimitz had no battleships left after the Pearl Harbor attack, and after the Battle of the Coral Sea there were only two flattops ready for action, Enterprise and Hornet. The Americans were able to count on Yorktown, however, after patching her up in an astonishing two days instead of 90 days as had been estimated. Yorktown and Task Force 17 were under the command of Rear Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher. The combined American force consisted of three carriers, eight cruisers, 15 destroyers, 12 submarines and 353 aircraft, ranged against a grand total of 200 Japanese vessels and 700 planes. While both Fletcher and Spruance were rear admirals, Fletcher was senior and nominally in overall command. When Yorktown was struck at Midway, however, Fletcher transferred his flag to the cruiser Astoria and placed Spruance tactically in charge.

With their 233 planes and crews at the ready, the three U.S. flattops were stationed well north of Midway, out of sight of enemy reconnaissance planes. The carriers were on station on June 2, and the following day Japanese transport ships were spotted 600 miles west of Midway Island. Because of gaps in the search patterns flown by the Japanese, the American carriers were able to approach unseen. Adding to the surprise factor was the fact that Admirals Yamamoto and Nagumo did not believe the U.S. Pacific Fleet was at sea.

Early on the morning of Thursday, June 4, 1942, Nagumo’s carriers launched a 108-plane strike against Midway and inflicted

serious damage on the island’s installations. For about 20 minutes, fighters, dive bombers and torpedo bombers pounded the island, carefully avoiding damaging the runways because the Japanese hoped to eventually use them. The small Marine Corps garrison scrambled its handful of Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat and Brewster F2A-3 Buffalo fighters, but they were too weak and slow to deter the Japanese. Fifteen Buffaloes and two Wildcats were lost, but the garrison’s anti-aircraft fire was effective. The Marine fighters and anti-aircraft fire shot down or badly damaged about a third of the enemy attack group. The first Japanese airstrike was followed by another.

At 8:20 a.m., Nagumo’s observers reported a group of American ships 200 miles away. His torpedo bombers–having switched to bombs for the attack on Midway–were away, and most of his protective fighters were out on patrol. So he changed course northeastward, avoiding the first wave of dive bombers launched against him from Spruance’s carriers. Nagumo ordered his planes rearmed on their return. Meanwhile, his search planes found no sign of any American warships. Then Nagumo was dumbfounded to receive a search plane’s report of 10 enemy ships to the northeast, where no U.S. ships were supposed to be.

After the enemy’s raids on Midway, Admiral Spruance ordered the launching of every possible plane to search for and attack the Japanese carriers. He decided to launch the planes from Enterprise and Hornet when they were about 175 miles from the enemy’s calculated position instead of postponing takeoff for another two hours in order to diminish the distance. Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat fighters, Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless dive bombers and Douglas TBD-1 Devastator torpedo bombers thundered off the flight decks and rose to search for the enemy carriers. By shortly after 9 a.m., planes from Yorktown were also on their way. It was a cool, clear day.

Aboard the battleship Yamato, Admiral Yamamoto received word that the U.S. fleet was at Midway–not Pearl Harbor as he had thought. Then Nagumo’s force was spotted by torpedo bombers from Hornet‘s squadron VT-8, led by Lt. Cmdr. John C. Waldron. The Japanese carriers were beginning to launch fighters as Torpedo 8 roared down to attack, without fighter cover. The slow-moving Devastators were easy targets for the Japanese gunners and Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters, and all 15 were shot down. The sole survivor of the squadron’s 30 officers and men was Ensign George H. Gay, Jr., who spent several hours floating in the water, watching the battle. Word of the sacrifice of VT-8 stunned the United States, and Churchill was reported to have wept when he heard about it.

The Japanese felt that they had won the encounter. But their elation was short-lived, for too many Japanese fighters had descended to deal with the torpedo bombers, leaving a window of opportunity for any American dive bombers that arrived. Two minutes later, 37 dive bombers from Enterprise, led by Lt. Cmdr. Clarence McClusky, swooped from 19,000 feet onto Nagumo’s ships. They met practically no opposition because most of the Zeros were still close to the water, not having had time to climb and counterattack. McClusky led one squadron, VB-6, against the carrier Kaga, while the other Enterprise squadron pounced on Nagumo’s flagship, Akagi. Lieutenant Commander Maxwell Leslie’s VB-3 from Yorktown attacked the carrier Soryu.

Aboard the Japanese flattops, many torpedo-carrying planes were waiting for fighters to take off as the American planes dived. Akagi was lashed by bombs, which exploded torpedoes that were being loaded onto her planes, and the crew abandoned ship. Yorktown‘s planes hit Soryu as she was turning into the wind to launch aircraft. Three bombs hammered her. Bombs destroyed the bridge of Kaga and set her ablaze from stem to stern. After six furious minutes, the three carriers were left burning. Akagi and Kaga subsequently went down. The Japanese were trying to tow Soryu to safety when she was torpedoed and sunk by the U.S. submarine Nautilus.

From the remaining enemy carrier, Hiryu, Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi launched bombers and torpedo planes against Yorktown. The gallant carrier was crippled but nearly succeeded in reaching safety before torpedoes from Japanese submarine I-68 finally sank her three days later. Retribution was not long in coming. On the afternoon of June 4, 24 American dive bombers–including 10 refugees from Yorktown–scored four hits on Hiryu. She went down with Admiral Yamaguchi, an outstanding flag officer who, it was said, would have been Yamamoto’s successor had he lived.

Admiral Yamamoto had hoped to fight a classic-style sea battle with battleships, but Spruance had proved that the aircraft carrier was now emerging as the capital ship of naval combat forces. The gloomy reports from Nagumo and his other commanders led Yamamoto to suspend his assault on Midway. He withdrew his ships westward, still hoping to draw Spruance into a trap. But the American commander, who could be daring and resourceful when necessary, could also exhibit shrewd caution when his experienced mind sensed an ambush.

Meanwhile, the Japanese attack on the Aleutian Islands had been carried out as planned on June 3. After air assaults, two rocky islands, Kiska and Attu, were occupied by Japanese ground forces. Japanese propagandists pointed to their success in the Aleutians to offset the defeat at Midway, but actually the Aleutians were of little strategic value. Covered by fog and lashed by storms most of the time, they were generally unsuitable for air or naval bases.

At Midway, Spruance’s force inflicted on the Imperial Japanese Navy its worst setback in 350 years. Four fleet carriers and the heavy cruiser Mikuma were sunk; a cruiser, three destroyers, an oiler and a battleship were damaged. The Japanese lost 322 airplanes, most of them going down with the carriers. The American losses were Yorktown, destroyer Hammann and 147 planes.

A number of strategic and tactical errors contributed to the Japanese defeat: Yamamoto’s virtual isolation on the bridge of Yamato and his failure to maintain an overall grip on the strategic situation; a loss of nerve on the part of Nagumo; tradition that led Yamaguchi and other enemy commanders to go down with their ships instead of trying to recover the initiative; insufficient reconnaissance against the U.S. carriers; a lack of high-altitude fighter cover; inadequate fire precautions aboard the ships; and the launching of airstrikes from all four fleet carriers at the same time, so that there was a critical period when the Japanese carrier force had little defensive capability. The Japanese had been overconfident, and the Americans taught them a bitter lesson.

Midway bought the United States valuable time until the new Essex-class fleet carriers became available at the end of the year. Above all, Midway was the turning point that heralded the ultimate defeat of Japan.

Admiral Nimitz praised Spruance for a remarkable job. Historian Morison later described Spruance’s performance at Midway as superb. Morison said: Keeping in his mind the picture of widely disparate forces, yet boldly seizing every opening, Raymond A. Spruance emerged from this battle one of the greatest fighting and thinking admirals in American naval history….He was bold and aggressive when the occasion demanded offensive tactics; cautious when pushing his luck too far might have lost the fruits of victory.

Spruance was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal, and in May 1943 he was promoted to vice admiral. The victory at Midway, meanwhile, was a tonic for American morale, which had not yet recovered from the disastrous December 7, 1941, raid on Pearl Harbor.

Raymond Spruance was born in Baltimore on July 3, 1886, the son of Alexander and Annie Spruance. He attended grade and high schools in East Orange, N.J., and in Indianapolis. He was a diligent, neat and gentle boy. His father wanted him to go to West Point, but young Raymond yearned to go to sea. He managed to gain an appointment from Indiana to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis. He readied himself at Stevens Preparatory School in Hoboken, N.J., and entered Annapolis in July 1903 at age 17. He studied hard, and when he graduated in September 1906, he stood 26th in his class.

After serving aboard the battleship Iowa, Spruance went on a world cruise aboard the battleship Minnesota. He was commissioned an ensign in 1908, and during a tour of shore duty he took a postgraduate course in electrical engineering in Schenectady, N.Y. He was then ordered to the China station, with sea duty aboard the battleship Connecticut and the cruiser Cincinnati. The young, ambitious officer was then assigned to Bainbridge, U.S. destroyer No. 1, and he commanded her until 1914. By that time, he was said to be an expert on the many engines, instruments and guns that go into a battleship.

On December 30, 1914, Spruance married Margaret Vance Dean, the daughter of an Indianapolis businessman. That same year he received a new assignment: assistant machinery inspector at the Newport News, Va., dry dock, where the battleship Pennsylvania was being outfitted. When she went to sea in 1916, he went with her.

I was shanghaied ashore in November of the next year to take over as electrical superintendent at the New York Navy Yard, said Spruance. I finally wangled two months at sea, in 1918, before the war was over. The following year, they made me executive officer of the transport Agamemnon, bringing troops home from France. It was interesting work, but I wouldn’t want to do it for a living.

More to his liking was the study of foreign methods of naval fire control, which took him to London and Edinburgh. His next assignment was command of the destroyer Aaron Ward, and then USS Perceval. His tour of sea duty ended in 1921, and he spent the next three years with the Navy Department’s Bureau of Engineering and the Doctrine of Aircraft board. Then followed two years as assistant chief of staff to the commander of naval forces in Europe; a year of study at the Naval War College in Newport, R.I., where he completed the senior course; and two years of duty in the Office of Naval Intelligence.

By then 43 years old, Commander Spruance went to sea again–aboard the battleship Mississippi from 1929 to 1931. Then he returned to the Naval War College as a staff member. He was promoted to captain in 1932, and the following year he was assigned as chief of staff and aide to the commander of a destroyer scouting force.

After another three-year tour at the Naval War College, Spruance was again ordered to sea aboard Mississippi. This was in July 1938, and this time he was the battleship’s commander. By 1939, at the age of 53, Spruance had spent 18 years at sea. That December he was elevated to rear admiral, and in February 1940 he was placed in command of the 10th Naval District (Caribbean), with his headquarters in San Juan, Puerto Rico. The following year, the new admiral was ordered to the Pacific.

Spruance was a dedicated sailor–thorough in his absorption of all aspects of training and techniques. His steady rise, according to Newsweek magazine, has borne the imprint of his personality–unobtrusive but undeviating. Early in his career he was

catalogued as someone to watch; there was never any possibility that he would be passed over in the lists for promotion.

Spruance’s performance at Midway so impressed Admiral Nimitz that he made him his chief of staff. His new duties involved planning rather than operations, and Spruance chafed for more action. His chance would come. When Nimitz named him commander of the disputed Central Pacific Area, this made him responsible for the planning and execution of the attack on the Gilbert Islands in November 1943. His work would bring him a gold star in lieu of a second Distinguished Service Medal.

The heavily fortified islands, former British possessions, were of strategic value because of their good landing strips and naval base. The assault began at dawn on November 20, 1943, and the fighting raged for 76 hours. The struggle by the U.S. Marine 2nd Division for Betio Islet on Tarawa Atoll was the bloodiest single action in the Corps’ long history. The American toll was 1,100 dead and almost 2,300 wounded. Only 17 of the island’s 4,690 Japanese defenders survived to become prisoners.

The Gilberts attack was planned and directed by Spruance, with the assistance of Rear Adms. Richmond Kelly Turner and Harry W. Hill and Marine Generals Holland M. Smith and Julian C. Smith. The airstrips in the Gilberts were put to good use two months later when they were used in the invasion of Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands. For that assault, Spruance led the most powerful naval strike force in history.

After three days of pre-invasion bombardment, Marines landed on Roi Islet and captured it the same day. One commentator said: The quick success of the offensive was attributed to the strategic daring by which Vice Admiral Spruance’s forces cut behind the eastern chain of the Marshalls. The Japanese had been battered for weeks by aerial bombardment, and knew the invasion was imminent. But they expected it to come at the obvious and exposed outer fringe, and when we struck at the heart of the archipelago with a huge fleet that had approached undetected, we enjoyed complete tactical surprise. Four days after the invasion, all immediate objectives had been taken, and by February 8, 1944, all organized resistance had ceased. Navy Secretary Frank Knox said of Kwajalein: The Japanese had been there 20 years. But we went in and took their possessions in a few days, without the loss of a single ship.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt nominated Spruance for promotion to full admiral on February 10, 1944, and he was approved. But due to a printing error on the executive calendar of nominations, Spruance was officially promoted only to his former rank of vice admiral.

Kwajalein was in American hands, but the rest of the Marshalls group–about 30 islands and more than 800 reefs scattered over hundreds of miles of ocean–remained to be dealt with. Spruance launched an assault on February 16-17 against Truk, the Japanese Pearl Harbor, at the same time that Admiral Turner’s forces were attacking Eniwetok Atoll in the Marshalls, about 700 miles to the west.

Spruance himself directed a task group of battleships, cruisers and destroyers that left the main body to go after Japanese ships that were fleeing Truk, sinking the light cruiser Katori and destroyer Maikaze. This was said to be the first time that a four-star admiral took part in a sea action aboard one of the ships engaged. The Japanese lost 19 ships sunk, seven probably sunk and more than 200 aircraft destroyed, and their installations were bombed and strafed. The Americans lost only 17 planes and no ships. Admiral Spruance commanded with deadly precision, reported an observer.

The American offensive in the Pacific theater was now enjoying considerable momentum, aided in no small measure by Rear Adm. Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58, the most powerful and destructive unit in the history of sea warfare. Five days after the Marshalls campaign, Spruance sent the Mitscher force to attack Tinian and Saipan in the Mariana Islands. The defenders fought fiercely but were unable to inflict any damage on the U.S. vessels.

>On March 29, 1944, Admiral Spruance took tactical command of a three-pronged assault against the Palau Islands, 550 miles east of the Philippines, and against Yap Island and Ulithi Atoll in the western Carolines. The three-day operation was the most extensive ever undertaken by carriers. U.S. losses were low: 25 airplanes and 18 lives. On April 22, Task Force 58’s guns and planes supported the U.S. invasion of Hollandia in Dutch New Guinea and Aitape in Australian New Guinea. On April 28, the last day of the invasion, Spruance’s command was redesignated as the Fifth Fleet. Admiral Halsey was given command of the Third Fleet, and later that year Task Force 58 was transferred to Halsey’s fleet.

Meanwhile, Task Force 58 was busy in the forefront of clearing the Japanese from the 600-mile-long Marianas chain. The Saipan campaign began with air attacks on June 10, 1944. Spruance’s naval guns started their bombardment two days later. On June 14, while Mitscher led a diversionary attack on the Bonin Islands 800 miles to the north, U.S. Marines and infantrymen stormed ashore. British Royal Navy units helped support the landings.

>A few days later, Mitscher rejoined Spruance and the Fifth Fleet. Both commanders hoped for a classic battle with the Imperial Japanese Navy, but only Mitscher’s carrier planes were able to reach the enemy. On June 19, however, hundreds of planes from nine Japanese aircraft carriers attacked the Fifth Fleet. They were hurled back decisively, and the losses–353 enemy planes downed, 21 U.S. aircraft lost–amazed the Americans. The Japanese managed to inflict only superficial damage on three ships.

Mitscher’s force pursued the Japanese fleet and engaged it the following day in the Philippine Sea, sinking the light carrier Hiyo and two oilers (in addition to which submarines Albacore and Cavalla had sunk Taiho and Shokaku the previous day). The score was 402 Japanese planes and six ships, with a loss of 122 planes from Mitscher’s flattops. Spruance’s fleet had prevented the Japanese from reinforcing the Saipan garrison. That achievement brought praise from Churchill, who wrote to Navy Secretary James Forrestal, Admiral Spruance is again to be congratulated for another fine job. My personal congratulations.

>The fleet units shielding the Marianas invasion forces were also under Spruance’s command. In the seven-week campaign, 55 Japanese ships were sunk, five probably sunk and 74 damaged. A total of 1,132 enemy planes were put out of action. The U.S. casualties were 199 planes, 128 flight personnel and damage to four warships. During the operation, the Fifth Fleet burned up 630 million gallons of fuel–more than the entire Pacific Fleet used in 1943.

Admiral Spruance’s last campaigns were the invasions of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, and he was awarded the Navy Cross for extraordinary heroism. The Fifth Fleet commander’s citation read: Responsible for the operation of a vast and complicated organization which included more than 500,000 men of the Army, Navy and Marine Corps, 318 combatant vessels and 1,139 auxiliary vessels, [he] directed the forces under his command with daring, courage and aggressiveness. Carrier units of his force penetrated waters of the Japanese homeland and Nansei Shoto. The Iwo Jima and Okinawa actions lasted from January to May 1945, and in August the Japanese surrendered.

Spruance was detached from command of the Fifth Fleet on November 8, 1945, and he relieved Fleet Admiral Nimitz as commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet and Pacific Ocean areas. He held that post until the following February, when he was ordered back to the Naval War College at Newport–this time as president. In October 1946 he was awarded the Army’s Distinguished Service Medal for his exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services during the capture of the Marshall and Mariana islands.

Shortly before leaving the Naval War College and retiring from the Navy on July 1, 1948, Admiral Spruance received a letter of commendation from the secretary of the Navy that read: Your brilliant record of achievement in World War II played a decisive part in our victory in the Pacific. At the crucial Battle of Midway, your daring and skilled leadership routed the enemy in the full tide of his advance and established the pattern of air-sea warfare which was to lead to his eventual capitulation.

Samuel Eliot Morison agreed: Power of decision and coolness in action were perhaps Spruance’s leading characteristics. He envied no one, rivaled no man, won the respect of almost everyone with whom he came in contact, and went ahead in his quiet way, winning victories for his country….When we come to the admirals who commanded at sea, and who directed a great battle, there was no one to equal Spruance. Always calm, always at peace with himself, Spruance had that ability which marks the great captain to make correct estimates and the right decisions in a fluid battle situation.

Summing up his appraisal of this outstanding sailor, Morison noted: Spruance in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, overriding Mitscher the carrier expert in letting the enemy planes come at him instead of going in search of them, won the second most decisive battle of the Pacific war. And, off Okinawa, Spruance never faltered in face of the destruction wrought by the kamikazes. It is regrettable that, owing to Spruance’s innate modesty and his refusal to create an image of himself in the public eye, he was never properly appreciated.

Spruance had earned a restful retirement at his home in Pebble Beach, Calif., 125 miles south of San Francisco, with his wife, son and daughter. But his service was not yet finished. President Harry S. Truman appointed him ambassador to the Philippines in January 1952, and he served until March 1955. Then it was back to Pebble Beach.

Spruance was an active man who thought nothing of walking eight or 10 miles a day. In the course of a two-hour interview, he stood or walked about all the time–not restlessly, but slowly and deliberately. He was fond of symphonic music, and his tastes were generally simple. He never smoked and drank little. He enjoyed hot chocolate and would make it for himself every morning. Besides his family, he loved the companionship of his pet schnauzer, Peter. Fit and spare in his 70s, Spruance spent most of his retirement days wearing old khakis and work shoes and working in his garden and greenhouse. He loved to show them to visitors.

Spruance became a shadowy sort of legend in the Navy. His achievements were well-known, but the man himself was a mystery. He did not discuss his private life, feelings, prejudices, hopes or fears, except perhaps with his family and his closest friends.

He was uniquely modest and candid about himself all his life. When I look at myself objectively, he wrote in retirement, I think that what success I may have achieved through life is largely due to the fact that I am a good judge of men. I am lazy, and I never have done things myself that I could get someone to do for me. I can thank heredity for a sound constitution, and myself for taking care of that constitution. About his intellect he was equally unpretentious: Some people believe that when I am quiet that I am thinking some deep and important thoughts, when the fact is that I am thinking of nothing at all. My mind is blank.

He lived quietly at Pebble Beach until December 13, 1969, when he died of arteriosclerosis at the age of 83. He was survived by his wife and a daughter, Mrs. Gerald S. Bogart of Newport, R.I. His only son, Navy Captain Edward D. Spruance, who served for 30 years, was killed in a car accident in Marin County, Calif., in May 1969.

Admiral Spruance was buried with full honors alongside Admirals Nimitz and Kelly Turner in a military cemetery overlooking San Francisco Bay. The Navy honored Spruance by giving his name to a new class of 30 destroyers, the first of which, USS Spruance, was launched in 1973. An academic building at the Naval War College was also named for him.

This article was written by Michael D. Hull and originally appeared in the May 1998 issue of World War II magazine. For more great articles subscribe to World War II magazine today!