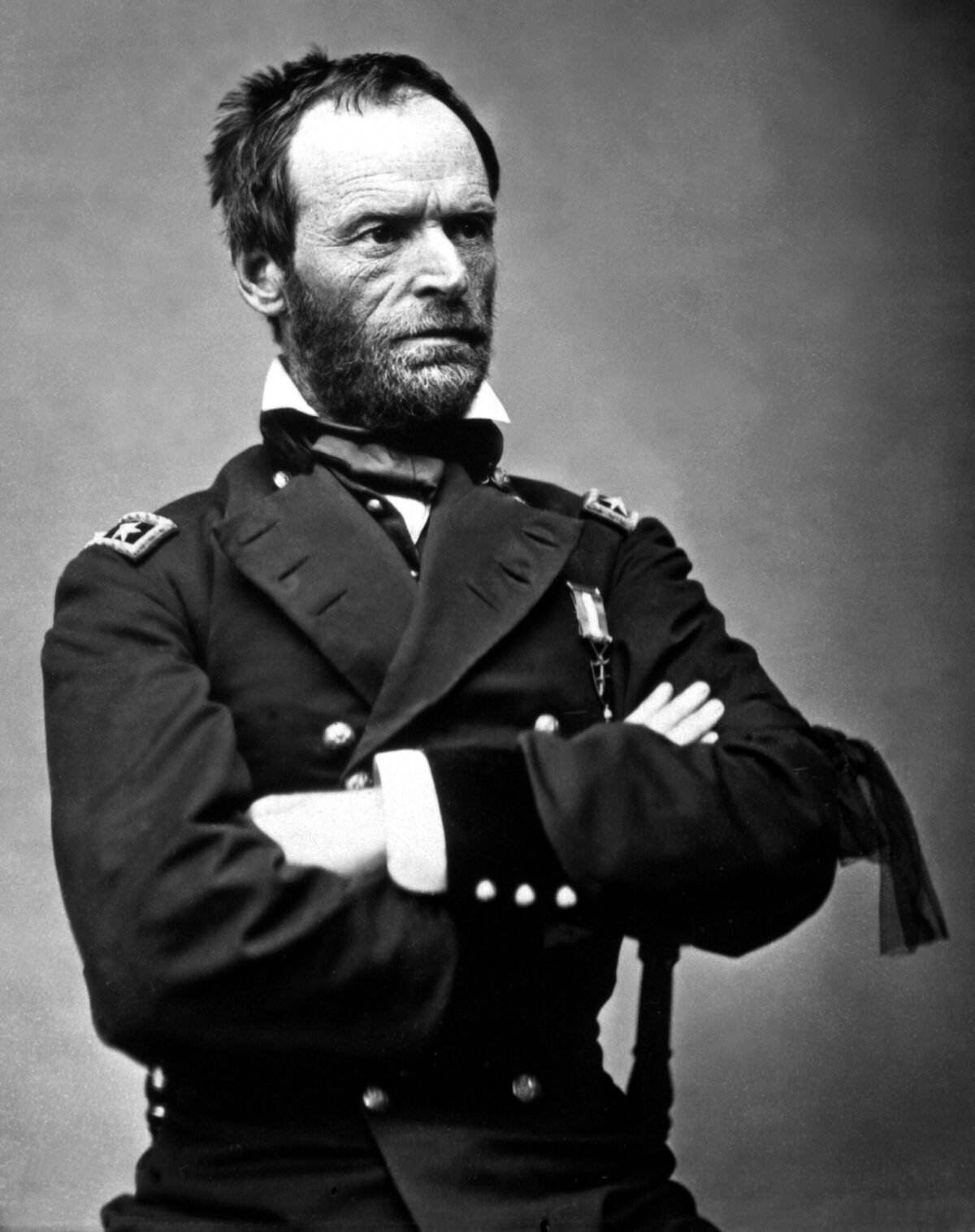

Working historians tend to Xerox first and think later. In trying to do all our research as quickly as possible, we collect reams of evidence from the archives and printed documents, most of which is ultimately forgettable and usually ends up in the recycle bin. This was almost the case when I came across a brief telegram in the Official Records, dated July 21, 1864, from William T. Sherman to Abraham Lincoln. It appeared to be a minor but friendly dispatch demonstrating Sherman’s acquiescence to the highest political authority of the land. Only much later, when I was working through the documentary materials surrounding this seemingly innocent missive, did I suddenly realize that Sherman was saying exactly the opposite of what his words appeared to mean.

It hit me like a bolt of lightning that, far from being cooperative, Sherman had been completely insubordinate, more profoundly and far more explicitly than even Douglas MacArthur was during the Korean War when he ignored President Harry S. Truman’s orders to stop his army well south of the Yalu River—the Chinese border—a move that provoked powerful Chinese intervention and thus prolonged and stalemated the war at great cost. For that, Truman famously sacked MacArthur.

None of the previous Sherman biographies had noted this major collision of military and civil authority, a fundamental danger to the American constitutional system during wars. Coincidentally, none had been much interested in Sherman’s racial attitudes, which given the rapidly evolving participation of newly emancipated African Americans in the Federal army, proved to be a profound policy issue dividing the military and Northern voters.

Immediately after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, his administration had put a major effort into creating a vast number of black troops. In part this policy answered growing manpower concerns—as the war ground on, fewer whites were enlisting, which led to the unpopular draft. Lincoln often argued for African-American enlistment in the most practical terms. As he wrote a conservative backer on August 26, 1863, trying to elicit his support on hardheaded grounds, “I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union.”

And yet in the same letter Lincoln revealed his idealism when he linked practical applications to a moral imperative: “If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom….And the promise made, must be kept.” He believed it would be morally liberating for black soldiers to fight for their own freedom, that they would later remember “with silent tongue and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation [of freedom].” As for white men who opposed using black troops “with malignant heart, and deceitful speech,” their spiritual dishonor would later come back to haunt them, Lincoln said.

At about the same time Ulysses S. Grant had written Lincoln that he had “given the subject of arming the negro my hearty support. [It is] the heaviest blow yet given the Confederacy. [They] will make good soldiers,” powerful allies, while simultaneously weakening the enemy “in the same proportions as they strengthen us.” As Lincoln and Grant believed would be the case, arming blacks proved to be a major upside for the Union Army, even though the men enlisted were often abused and treated as second-class soldiers.

Sherman disagreed vehemently with this policy, and did everything in his power to negate it. When black troops were first recruited in April 1863, he wrote his wife: “I would prefer to have this a white man’s war….With my opinion of negroes and my experience, yea prejudice, I cannot trust them yet…with arms in positions of danger.”

Later that year Sherman wrote Henry Halleck that Confederates would submit only to white soldiers fighting courageously for a pure purpose, “to sustain a government capable of vindicating its just and rightful authority, independent of n——s, cotton, money, or any earthly interest.” Even after the Emancipation Proclamation, Sherman was still fighting for the Union, not for the freedman.

When Lorenzo Thomas, adjutant general of the Army, came west on an African-American recruiting drive that spring, he addressed Sherman’s assembled men, explaining that they would have to adjust to this new policy. Sherman followed, telling his soldiers he hoped the policy could be revised, and “that they should be used for some side purpose & not be brigaded with white men.” Reporting this speech to his brother John, the senator from Ohio, Sherman added his opinion that blacks “desert the moment danger threatens.…At Shiloh all our n—— servants fled…I won’t trust n——s to fight yet.”

The following spring Thomas made another recruiting trip in the West. This time he wrote to Sherman, now in charge of the entire Federal army in the West, that he expected “full cooperation on the part of all military commanders to enable me to execute these special orders of the Secretary of War….”

Despite this clear policy enunciation, Sherman issued a special order of his own that any recruitment officer who tried to enlist black laborers as soldiers would be arrested. Then, as his army began its summer campaign, he wrote additional letters refusing black enlistment. On July 14 in the trenches around Atlanta, he wrote Halleck, in a letter he must have known would be passed on to Stanton and Lincoln, “I must express my opinion that [black recruitment] is the height of folly.” As for Lorenzo Thomas’ recruiters, he said, “I will not have a set of fellows here hanging around on any such pretences.”

Finally, after all the normal military routes to a theater commander had failed, on July 18 Lincoln himself issued a direct order to Sherman: “To be candid I was for the passage [of the recruitment law]. I still hope advantage from the law; and, being a law, it must be treated as such by all of us.…May I ask therefore that you will give your hearty cooperation?”

In this context, the meaning of Sherman’s July 21, 1864, telegram was crystal clear. “I have the highest veneration for the law,” he telegraphed the president in reply, “and will respect it always, however it conflicts with my opinion of its propriety.” It seemed Sherman would obey Lincoln’s order, but then he added, “When I have taken Atlanta and can sit down in some peace I will convey by letter a fuller expression of my views.”

Whatever Sherman’s abstract understanding of the constitutional subordination of the military to the national executive might have been, he was in fact refusing to obey a presidential order. That was outright insubordination, slightly softened only by his promise to respond later in full. But even then, Sherman appeared to be saying that he would continue to stonewall indefinitely, that he would refuse to implement a major policy directive.

Why then did Lincoln not relieve Sherman the moment he received this telegram, as Truman fired MacArthur in a parallel situation? For one, Lincoln’s political fortunes were in a disastrous trough. After a brutal and indecisive campaign, Grant was now bogged down in the trenches at Petersburg, and war weariness was rampant in the North. Lincoln fully expected to be defeated in the approaching elections. Only Sherman might rescue him if he took Atlanta.

Sherman, of course, was playing a ruthless political game. He believed Lincoln was in no position to reprimand him or impose any policy on him. And in that he was right. Under these terrible circumstances, Lincoln put up with Sherman, hoping that the capitulation of Atlanta would serve his antislavery war aims despite the general in charge. He rank-ordered his priorities.

Lincoln’s calculation paid off. Atlanta fell on September 1, and Northern opinion concerning the war turned on a dime. Two months later Lincoln won a smashing electoral victory, in significant measure due to the generalship of his insubordinate commander in the West. Ironically, this bitterly prejudiced general served the ultimately victorious antislavery war policy of the Lincoln administration.

The week after claiming he was too rushed to think about acquiescing to Lincoln’s order, Sherman found time to reaffirm his defiant political sentiments in a letter to John A. Spooner, recruitment agent for black soldiers in Massachusetts. Sherman told Spooner to share the letter with other state agents, and sent copies to many of his military subordinates.

Sherman wrote Spooner that he opposed the policy because “the negro is in a transition state, and not the equal of the white man….I prefer some negroes as pioneers, cooks and servants, others gradually to experiment in the art of the soldier [with] the duties of local garrisons,” and none at all with his frontline forces. When news of the correspondence spread, he wrote to a friend: “I never thought my n—— letter would get into the press….I lay low. I like n——s well enough as n——s, but when fools and idiots try and make n——s better than ourselves, I have an opinion.”

In the coming weeks, Sherman remained furious about black recruitment, often referring to the dangers of enlisting “n——s and vagabonds,” who would prove to be worthless, cowardly, slothful “trash.” When Atlanta fell, Sherman wrote to Halleck, “I hope anything I said or done will not be construed unfriendly to Mr. Lincoln or Stanton.” He had never intended his Spooner letter for publication, he professed, but now he urged Lincoln, through Halleck, to drop the policy, saying, “I am honest in my belief that it is not fair to our men to count negroes as equals.” Yes, a negro might be “as good as a white man to stop a bullet [but] a sand bag is better.” Black troops were incapable, he believed, of skirmishing, improvising roads and creating spontaneous flanking movements.

Many in Washington began writing Sherman that he was both pigheaded and wrong in his opinions, including key allies such as Halleck, Samuel Chase and his own brother. After Sherman’s army had taken Savannah, Ga., at the end of his March to the Sea, Edwin Stanton came down by cutter to impose on Sherman a regiment of black troops that he had brought with him. Sherman, however, disarmed the black soldiers and gave them spades. His white troops rioted against the newcomers, killing at least three and reminding them that they had no place in this army, which remained lily-white until war’s end.

In what is perhaps the greatest irony of all, at Stanton’s urging, Sherman issued his Special Field Orders No. 15, which gave former slaves 40 acres of land, taken from the plantations of Confederates who had fled. This radical act seemed to absolve Sherman of his racist reputation while providing an alternative for the blacks who wanted to fight in his army. It was perhaps the single most dramatic act in race relations during the Civil War, and William T. Sherman, Negrophobe, was its effective father.

Sherman relished exercising control of his army’s racial composition, and he enjoyed fighting the administration over issues of racial equality. Lincoln managed to keep his cool. Sherman, he knew, was of more use as head of the Union army in the West than as an ex-commander.

This all exemplifies the often breathtakingly high level of the political struggle during this antislavery war, not just against the Confederacy but also within the Union, even the Army. Lincoln did not feel unconstrained enough to assert his authority as commander in chief to impose policy on this wildest of generals and fire him when he disobeyed—not just once, but over years. Other generals, particularly George McClellan, dragged their feet and sought to fight a less than fully committed war. Only Sherman was so insubordinate—and unlike McClellan, he got away with it. But Sherman’s vigorous and imaginative generalship and timely victories served Lincoln’s larger political goals, with which the general strongly disagreed.

And it all turned on that seemingly innocuous telegram!