Birdsong greeted me as I arrived on a crisp spring morning. A pale sun hung in a blue sky. It was one of those days when you can feel nature emerging from winter recess. The birds seemed to sense the shift, tweeting from the beech trees that gave the place its name—Buchenwald.

I had arrived early at the concentration camp memorial, the first visitor that day through wrought iron gates whose inscription declares Jedem das Seine (literally, “To each his own”; colloquially, “We get what we deserve”). I closed the gate behind me, walking out of the watchtower’s shadow and into sunshine on what once was the camp’s muster ground. I listened to the birds, trying my hardest to imagine the scene here 70 years ago; I could not.

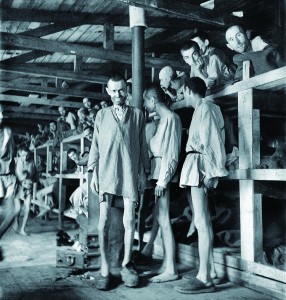

However, I could recall a British film I had watched recently, Night Will Fall, and that 2014 documentary’s gruesome account of the Allied liberation of the camps. I remembered the words of one of the first Americans into Buchenwald in April 1945. Sergeant Benjamin B. Ferencz was a GI with General George S. Patton’s Third Army. “You couldn’t tell if they were dead or alive,” Ferencz, in civilian life an attorney who later served as Chief Prosecutor for the Nuremberg trials, said of the inmates. “You’d step over a body and they would suddenly wave at you or raise a hand…. The smell of the camps, the crematorium was still going, the dead bodies piled up like cordwood in front of the crematorium. It’s hard to imagine for a normal human mind. I had peered into hell.”

How does one turn hell into a place of pilgrimage? With sensitivity, of course, but also without sanitization. In many ways the simplicity of the Buchenwald Memorial and the silence of its surroundings convey this diabolical story.

Visitor center guide in hand, I walked the few hundred yards to the camp’s main gate, past buildings that once held SS guards. I read as I walked. One can watch a short introductory film as well; I knew the basics. I learned that the Germans built Buchenwald in 1937. The site is six miles northwest of the city that was the creative hub of the German Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries: Weimar, where 20th-century residents jeered at wretches being carted to the rail station, bound for Buchenwald. Initially, the guide booklet said, the camp was to hold those with “no place in the National Socialist people’s community”: political dissidents, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, Gypsies.

Once the war began, Buchenwald became a labor camp populated by slaves from across Europe. Prisoners of war, civilians, young, old; by 1945 some 250,000 people had come to Buchenwald. Approximately 56,000 died—from disease, overwork, starvation, and medical experimentation. Guards murdered a minority in horrible intimacy.

Moving counterclockwise from the gate, I came to the crematorium—six brick ovens served by an electric elevator that stoked the flames with human fuel. The ovens have been preserved in original form. The masonry work is clean; so, too, the cast-iron doors, always open. Through a window I studied an open stretch of ground. Fifty yards or so away, beyond the fence, I could see a cluster of stone and masonry ruins and made a note to take a closer look.

The ovens are not the crematorium complex’s most chilling touch; that comes in rooms at either side. One housed the pathology department, a small space dominated by an autopsy table with two enamel basins. At the far end, a glass cabinet displays medical instruments: hacksaw, tweezers, mallet, scalpel. Benign on their faces, these implements saw use during the Nazi era, one of many signs explains, to remove gold teeth from corpses and in the “production of articles from human skin and human heads.” Unproven rumor has it that Ilse Koch, wife of Buchenwald’s first commandant, owned at least one lampshade made from human skin. A pathology annex has over the years been transformed into a shrine, adorned with memorial plaques and tablets placed by relatives of inmates who never left Buchenwald. The names of the dead are Russian, Belgian, Italian, German, Bulgarian, Polish, British, a borderless realm of death and sadness. The heartfelt simplicity of the memorial plaques is deeply affecting. One, which names a Frenchman, reads simply, “For my dear son. 1921-1944.”

On the other side of the crematorium is a low-ceilinged basement that was closed to the public for repairs the day I visited. In German it’s der Leichenkeller—the mortuary cellar. Standing by the crematorium elevator hatch, I could see into the downstairs space. Originally camp managers stored bodies there until they could be burned, but as Buchenwald grew, guards converted the basement into an execution chamber. They led more than 1,000 inmates down the steps to be garroted, then stuck on one of the meat hooks mounted near the ceiling. Those who did not die quickly enough were finished off with wooden clubs wielded by guards

Leaving the crematorium, I resurfaced to blue sky and birdsong, and a Buchenwald swelling with visitors. I noticed one or two English and American accents, but most were German, and youngsters at that.

My next stop was the disinfection station, which now houses sketches and drawings prisoners created here, works of art that illustrate the strength of the human spirit. Painter turned French Resistance hero Boris Taslitzky, for example, made more than 100 sketches of life in Buchenwald on scraps of stationery stolen from guards. One from 1945 depicts two wasted inmates asleep at a table. Taslitzky titled it, “Exhausted comrades wait to be summoned.”

Next door to the gallery is Buchenwald’s main exhibit, in the former depot where incoming inmates, by now clad in striped uniforms of blue and gray, had their clothing and possessions taken from them. Artifacts, documents, and photographs tell how Buchenwald came to be and came to grief.

Besides these highlights Buchenwald’s 470 acres contain so much history that one needs a full day to absorb what was done in this peaceful corner of Germany—and not only by Germans. From 1945 to 1950, the Soviet secret police interned 28,000 people here at what they called “NKVD Special Camp No. 2”; a separate display on that period details the experiences of those guests of the U.S.S.R.

Some Buchenwald history asserts itself in absentia. Walking from the depot, I wove among neat rectangles of black copper slag, each delineating the wartime location of an inmate barracks. I exited through the main gate, beneath the watchtower, and followed a path beyond the fence that brought me to the masonry pile I had seen from the crematorium. A sign read, “The zoological garden of the SS.” Beside the placard was a photograph taken in 1938 of two bear cubs cavorting where I stood. I looked up and saw the crematorium chimney. So this was how off-duty SS officers and their families relaxed: in a bear garden, a stone’s throw from the ovens.

That evening at my hotel in Weimar I fell into conversation with two fellow tourists. One of these young German women taught English in a high school. As our chat was winding up, curiosity led me to broach the subject of Buchenwald. I briefly described my visit to the camp, commenting that most of my fellow visitors had been German youths on school field trips. Was this common, I asked. Was it necessary? These things happened 70 years ago, after all, I said; perhaps it was time to look to the future and not dwell on ancestral sins.

“What happened was a long time ago,” the teacher said. “But Germany must never forget what it did.”

Originally published in the May/June 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.