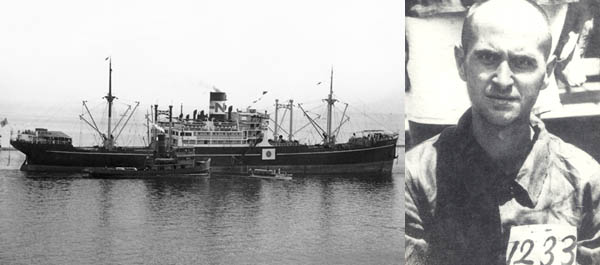

On the morning of July 17, 1944, U.S. Army private Andrew Aquila, 26, stood in a line of 1,600 American prisoners of war that stretched down Pier 7 of Manila Harbor. It was early, but the men were already sweltering under the rising tropical sun. Sent to Manila from POW camps throughout the Philippines, the prisoners waited to board the 6,527-ton, 420-foot Nissyo Maru, a rusting Japanese cargo ship that seemed barely seaworthy.

Nothing was worse than a World War II Japanese POW camp—except a trip on a prisoner transport ship

Shouts from the Japanese guards started the line of men moving forward. Aquila, clad only in tattered, cutoff dungarees, slung the canvas bag with his few possessions over his shoulder. He checked his pocket for the ball of rice he’d been issued, felt his half-full canteen on his belt, and finally patted the small pocket on the inside of his shorts, checking for his high school ring, which he’d managed to keep hidden from the guards. The youngest of eight children, Aquila had been the first in his family to graduate; his older siblings had all been forced to quit school and go to work when their father died. The ring was important, a thing of pride, but also a reminder of a place outside the hell he’d lived through since the American surrender on Bataan two years before. Every time he touched it and felt the cold, smooth gold, he knew he’d do all he could to get back home to his Italian neighborhood in Cleveland. He wondered about his family. Had any of his three brothers been drafted? Were they fighting? Were they even alive?

Another round of shouts from the guards snapped him back to reality, and he started up the gangplank. Barbarous treatment from the Japanese, harsh labor details, starvation, and disease had worn down his five-foot-eight frame to just 85 pounds, about half his normal weight. Like the others, he was suffering from dysentery, dengue fever, beriberi, malaria, and malnutrition. Still, Aquila felt lucky to be alive.

He’d already lived through so much. Drafted in 1941, he had arrived in Manila two weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor. A headquarters messenger with B Company of the 192nd Tank Battalion, he had taken part in the heavy fighting on Luzon after the Japanese invaded. He had survived the infamous Bataan Death March that killed thousands, and the nightmare of Camp O’Donnell, his first prison, where grisly conditions and rampant disease killed an average of 300 men every day. Next, at the Cabanatuan prison camp, he’d become so sick that he’d been sent to what the men called the Zero Ward, a dark hut that housed prisoners the doctors felt had no chance of living. Aquila had made it, and over time, he had grown accustomed to deeper and deeper levels of a hellish existence that few could imagine. But as he boarded the ship, he didn’t know that an even worse hell awaited him.

From the start, the Japanese bolstered their war effort at home by using “liberated” civilian populations and POWs as workers in factories, fields, mines, and mills. Prisoners were invariably given the most difficult and dangerous jobs.

To bring the POWs to Japan, the Japanese used transports that would earn the name “hellships.” By 1944 these ships were carrying prisoners in numbers six times greater than what the Japanese had deemed acceptable at the beginning of the war. This practice, called chomansai, or super-full capacity, gave each man less than one square yard of space for voyages that lasted up to 70 days. The crowded, disease-ridden conditions, says historian Gavin Daws, were comparable to those on the slave ships of the 18th century.

Adding to the horror was the chance that Allies would sink these ships. Among combatants on both sides, the Japanese alone refused to guarantee the safety of POWs at sea or mark their prisoner transports. Friendly fire accounted for a staggering 93 percent of the POW deaths on these ships, according to Gregory Michno, author of Death on the Hellships.

Conservative estimates suggest that, in all, 50,000 Allied POWs boarded hellships during the war. Michno says that 21,000 didn’t survive—more deaths than were sustained in combat by the U.S. Marines during the entire Pacific campaign.

****

On board the Nissyo Maru, the guards moved the men toward the rear of the ship and had them remove their shoes and drop their bags through a hatch into hold number three. The men were then directed to a narrow, wooden stairway that led into the dark hold. “I was in one of the first groups to go down,” Aquila recalls. “I remember that heat. It just came up at you like a furnace.”

As his eyes adjusted, Aquila saw a series of long wooden tiers that lined the forward, starboard, and aft sides of the hold. There were three levels, each about 4 feet high and around 10 feet deep. At the guard’s orders, Aquila got into the lowest tier on the forward wall. “They motioned for us to sit in rows with our legs open so that the next guy in front of us could sit in between them, back to chest. They just kept packing us in.”

The Japanese seemed intent on cramming in all 1,600 prisoners. To make more room, the guards had the prisoners put the baggage into another hold directly below. Though the tiers were soon filled, the guards kept shoving in more men. Those who could move their arms twirled their shirts above their heads to stir the air. “It’s too hot in here!” men shouted. “I can’t breathe!” More men kept coming. The heat grew more oppressive. On deck the guards shouted and beat anyone who refused to go into the hold. Fights broke out as men vied for space and struggled to breathe.

Soon, the pressure of bodies pinned each man’s arms to his sides. “Movement occurred only in mass waves, like jelly in slow motion,” remembered one survivor. Men fainted; some fell and got trampled. The men lifted some of the unconscious above the crowd and passed them hand over hand back up the stairs and onto the deck. Panic set in. Prayers mixed with curses and screams echoed off the steel walls of the hold. Those with water quickly drank it or risked having their canteens stolen. The desperate began to drink their own urine.

The guards kept screaming, pressing in more men. They shoved and clubbed those near them, kicking back to consciousness those who’d been passed up to the deck. “There was so much panic and noise. Men were losing their minds,” says Aquila. “I felt trapped, but I couldn’t do anything. It was getting hotter and I was having a lot of trouble breathing. I knew that if I let myself go, I would have passed out. So I just tried to hang on and stay as calm as I could. Then I started to pray. That helped me. I did a lot of praying.”

Finally, hold number two, just forward of the bridge, was opened. Some 900 of the men were ordered there, leaving roughly 700 in number three, a space that would have comfortably held no more than a hundred. No one knows how many prisoners died that first morning, but the hell of the voyage had only just started.

****

Around 9 p.m., the Japanese lowered a few large wooden buckets of steamed rice into the hold. There was no organized system of distribution yet, so men too weak to move did not eat. Many who did get some rice found their mouths were too dry to swallow.

“That first night was pretty rough,” Aquila remembers. “We hadn’t had any water and we were all in bad shape. A lot of men were screaming and moaning. Most of us had dysentery but there was nowhere for us to go. People just went where they were. No one slept that night, so I just kept praying and hoped for the best.”

The Nissyo Maru left the dock the next morning and anchored farther out in Manila Bay. It would wait there a week for the other elements of Convoy HI 68, which had left Singapore on July 14. Once assembled in Manila, the group was to head to Formosa, then Japan.

Some 30 hours after the men boarded, they were given their first water ration. Throughout their voyage, each man was issued no more than a pint a day, despite temperatures in the hold that topped 120 degrees. “If the hatch was open,” Aquila says, “we would stand under it when it rained and try to catch some of the drops in our mouths or in our canteen cups. Other guys were so thirsty they kept drinking urine. I felt bad for them. But that thirst was always there, and it made us all a little crazy.” Some used pieces of their clothing to soak up condensation on the rusty, metal hull, wringing this foul liquid into their mouths. One man went berserk, ripped open another’s throat, and drank his blood. When water was sent down, the guards laughed at the mad scramble of the prisoners.

Eventually, the Japanese lowered into the hold wooden buckets to use as latrines. They also set up on deck a benjo—a small, wooden outhouse built over the side of the ship. “But we were all so sick with dysentery and we couldn’t control it,” Aquila remembers. The buckets were always overflowing and spilling. “It was filthy and we just had to live in it.” The stench in the hold was overwhelming, especially when the hatch was closed.

Aquila tried to stay positive. He knew this would help him make it through yet another level of hell. He and the POWs on board were, above all, survivors. Their years of captivity had taught them how to adapt and live with horror. Those who couldn’t were already dead.

During the week in Manila Bay, the men tried to establish some sort of routine. “Most of the day was spent waiting in line,” Aquila remembers. “We’d wait in line twice a day when food and water were distributed. Then we’d wait hours for the benjo. We’d go up, then come down, and get right back in line because we knew we’d have to go again in a little while.”

A few men foraged for food in the bags stowed in the lower hold. When someone found one belonging to a Catholic priest, some prisoners ate communion wafers with their rice that evening.

On July 24, other elements of Convoy HI 68 arrived in Manila Bay. There were 21 ships in all—four transports, six tankers, two landing ships, a seaplane tender, and seven escorts. The convoy headed north, toward Formosa, and a new danger.

At dawn on July 25, the USS Angler, one of three submarines patrolling the South China Sea, spotted the convoy and flashed word to its sister subs the USS Crevalle and the USS Flasher. The three were known as Whitaker’s Wolves, after Lieutenant Commander Reuben Whitaker, skipper of the Flasher.

At 12:22 p.m., the Crevalle went to battle stations, submerged, and fired four of its stern tube torpedoes at the two largest freighters on the port side of the convoy, the Aki and Tosan Maru. All four missed. The Japanese, now aware of the enemy, began dropping depth charges.

After dark, the USS Flasher surfaced and regained contact with the convoy. A little after 2 the next morning, the Flasher radioed the other two subs that it was beginning the attack. Still surfaced, it fired six torpedoes at the same two freighters the Crevalle had missed.

The watch on the Aki Maru saw the trails approaching. The ship turned hard to port, only to be hit in the bow. Twelve men were killed in the explosion. Right behind it, the Tosan Maru was hit twice. The ship started to drift, and fires broke out on board.

The shrieking whistle of the ship’s alarm woke the men in the holds of the Nissyo Maru. “It was pitch black,” Aquila says, “but we could all feel the ship vibrating as it picked up speed and then began to move in a zigzag. Men began shouting, ‘What’s going on?’”

Aquila heard the Japanese ship drop depth charges, followed by the deep thuds when they exploded. Then some of the navy men started to shout, “Torpedoes! Torpedoes are in the water! They’re going under the ship!”

“Men started to really panic,” Aquila says. Two of the Flasher’s torpedoes missed their targets on the convoy’s port side but hit the tanker Otoriyama Maru, which was in the middle of the column.

“All of a sudden we heard this big explosion,” Aquila says, “and the ship rocked. We saw this wall of flames come over the top of the hatch, and our hold just lit up like daytime.”

The Otoriyama’s cargo of gasoline had exploded; the ship went down in minutes. Men on the Nissyo Maru remember hearing a boiling hiss as the burning metal of the hull slipped under the sea. Unexpectedly, the bright light from the explosion outlined the USS Flasher, and the submarine was forced to dive as the Japanese escorts fired frantically on its position.

The attack continued, along with the panic in both holds. The men in the third hold ran for the staircase, pushing and screaming, “Get me out of here!”

“I’ve never seen so much horror,” Aquila says. “I remember fingering my ring and just closing my eyes. I was so scared at that point that I felt numb. It was almost like I was hovering over everything and watching the whole thing from above. We were expecting to be hit any second.”

As the panic increased, guards at the hatches to both holds pointed machine guns down and warned that they would open fire. Just as the guards looked as though they would shoot, one of the chaplains, Father John Curran, worked his way onto the staircase. “Now there’s nothing we can do about this, men,” he said. “So let’s go ahead and start praying.”

“His voice was so sure, and it calmed everyone down right away,” Aquila remembers. “Then he led us in prayer for the rest of the attack.”

Whitaker’s Wolves eventually sank two freighters, the Aki Maru and Tosan Maru, in addition to the tanker Otoriyama Maru. They also severely damaged the tender Kiyokawa Maru. About 30 hours after first firing on the convoy, the submarines disengaged, their cache of torpedoes nearly spent. The American sailors had no idea how close they had come to killing 1,600 of their countrymen.

****

The Nissyo Maru put into dock at Takao, Formosa, at 1 p.m. on July 27, ten days after the American prisoners boarded. A large cargo of sugar was loaded into the lower hold below hold two. The convoy was reorganized, and the transport and a dozen other ships went on to Japan. Finally, at 4 p.m. on August 3, after an uneventful but choppy week at sea, Convoy HI 68 arrived at the port of Moji on the Japanese island of Kyushu. “We came up on deck and I’ll tell you, it felt so good when that fresh air hit us,” Aquila remembers. “I just kept breathing it in as deeply as I could. We were all filthy and we were sick but we were alive. I remember thinking, ‘I made it again. I’m still alive, thank God. I made it again.’”

The ordeal of the men aboard the hellship Nissyo Maru was finally over; official records put the death toll of prisoners at 12. After disembarking, Aquila and the other men in hold three were sprayed with DDT, put onto trolleys, then transported to Fukuoka Prison Camp 3, where they went to work in the Yawata steel mills. The men in hold two were sent to different POW camps throughout Kyushu.

Aquila endured another 13 months of brutal captivity before Japan surrendered and U.S. forces landed on Kyushu. His work days began at dawn, and he and the other Americans spent long hours shoveling iron ore, hauling bricks, and cleaning hot furnaces. At their prison camp, the guards beat them severely, particularly after American air raids. Men who fought back were killed.

Sixty-seven years later, time has smoothed the sharpness of Aquila’s memories from his years as a POW. But those 18 days of horror aboard the Nissyo Maru won’t fade away easily. “That ship was the worst of it,” says Aquila, now 93, while rubbing the high school ring he still wears. “But you know, I made it. And I almost feel like the rest of my life has been a bonus for me, a gift. Just like frosting on the cake.”