“It was a great day for flying,” my father always said afterward. But August 24, 1943, turned out to be a thoroughly bad day for the crews of seven Consolidated B-24D Liberators of the 425th Squadron, 308th Bomb Group (Heavy), on a mission to Hankow, in Japanese-held China.

On that day my dad, 24-year-old aircraft commander 1st Lt. John T. Foster, and the rest of the crew of B-24D No. 42-40879, dubbed Belle Starr, were awakened at 4 a.m. in Kunming and briefed on the mission. For the recently formed heavy bomber force of Maj. Gen. Claire Chennault’s Fourteenth Air Force, this would be only the 15th mission.

The crews were well aware that they were on their way to the scene of a recent bloodbath. Just three days earlier, a group of Liberators based at Chengkung—14 B-24s from the 374th and 375th squadrons of the 308th Bomb Group—had bombed Hankow. Leading that flight was Major Walter “Bruce” Beat of the 374th. They flew to the rendezvous spot over the fighter field at Hengyang, but when a promised escort of Curtiss P-40s and Lockheed P-38s failed to appear, Beat decided to continue on to the target without any escort.

As the B-24s approached Hankow, they were met by a swarm of an estimated 60 Japanese fighters, which pounced on the lead squadron’s ships. Almost immediately, Beat’s Rum Runner burst into flames amidships, then exploded. Seeing that, as one co-pilot of another B-24 said, “We just poured on all the power we could to get the hell out of there.” Only one plane of the 374th and six of the 375th returned, carrying badly wounded crewmen.

The 308th’s commander, Colonel Eugene H. Beebe, watched as the shattered survivors landed at Kweilin. One crewman recalled: “Colonel Beebe didn’t say a word. He just stood there with tears streaming down his face as he saw the condition we all were in.”

Now, three days later, the 308th was going back to Hankow. For dad and the rest of Belle Starr’s crew, it would be their first combat mission since their arrival in China three weeks earlier.

My father grew up near Waterbury, Conn., but his earliest childhood years had been spent in Changsha, China, where my grandfather taught medicine. When civil unrest made life there risky for foreigners, he and his family slipped out of Changsha on a cold foggy morning in January 1927 in a small riverboat, making a stop at Hankow, then on to Shanghai and the ocean liner that took them back to the States.

Dad graduated from college in 1940 and after a year of selling insurance enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces in September 1941. He had never even been inside a plane and had no particular interest in flying, but it seemed preferable to a life “in the mud” as an infantryman. Once he was accepted, he went to an airfield and paid $5 for his first ride—just to see what it was like.

Ten days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, dad was inducted. During primary training, he later recalled, “It was soon clear, to me at least, that I really wasn’t cut out for all this, and in the first weeks I was confused, disoriented and scared.” In advanced flying school some cadets found they could put holes through the target sleeve in aerial gunnery drills, while others could not. Cadet Foster was among the latter, and he was assigned to B-17 training. In an August 1942 letter to his parents, he rationalized: “We’re all pretty satisfied with this heavy stuff. Not so glamorous as pursuit, but it is important and [it is] the offensive end. At the same time it’s the safer branch of flying.” The B-17s and B-24s, he had been told, “are so well defended that the Japs just aren’t attacking formations”!

Their instructors told them how lucky they were to be in B-17s, not the homely, slab-sided B-24s—“the box the B-17 came in.” But his graduation was followed by orders to Tucson and crew training. In the B-24.

In mid-June 1943, the crew was assigned a factory-new B-24D, one with the newly introduced “hi-tech” ball turret in the belly, and learned they were headed for the China-Burma-India Theater. Before they left the States, a former Disney artist airbrushed a sexy cowgirl and the name Belle Starr on the nose of 42-40879.

In later years my dad mused: “Let it be said that I never boasted of having much flying skill. Yet the Army Air Forces was handing me a fresh new quarter-million-dollar B-24, telling me, at age 24, to fly myself and my crew to China on my own. Was the Air Force so desperate? Or so overconfident?” His crew included Lieutenant Sheldon Chambers, co-pilot; Lieutenant Harry Rosenburg, navigator; Lieutenant Lionel “Jess” Young, bombardier; Tech. Sgt. Bill Gieseke, engineer and top turret gunner; Tech. Sgt. Jack Miller, assistant engineer and gunner; Staff Sgt. Alvin Hutchinson, ball turret gunner; Staff Sgt. Ray Reed, tail turret gunner; Staff Sgt. Don Smith, radioman and waist gunner; and Staff Sgt. Ray Pannelle, armorer and waist gunner.

Belle Starr left Homestead, Fla., headed for Trinidad, then Belem and Natal. After that came the hop across the Atlantic to Ascension Island, and finally on to Chabua, India—the primary supply station for the 308th Bomb Group. The next day Belle Starr made its first crossing of the Himalayas—“the Hump”—and continued on to Kunming, where it would be based.

After pulling the B-24 into a revetment, the weary fliers relaxed, pleased that their nine-day, 12,000-mile trip had at last come to an end. But while they were still in their seats, filling out the usual reports, the crew got a shock. “Alongside came a truck,” dad recalled, “and with it came a carrier piled with very real bombs and, as one group of men hurriedly threw boxes and baggage from our airplane onto one part of the truck, others were bringing aboard boxes of .50-caliber ammunition and pushing the bomb carrier under the bomb bay and starting to load. Someone said, ‘We have a mission in the morning.’ I was stunned because throughout our bomber training there had been the consistent message that when we reached our particular war zone there would be a period of training in local tactics.”

After a restless night, my father was told early the next morning that Belle Starr had a fuel leak, so they wouldn’t be going along on that mission after all. “I don’t remember going back to sleep, but I do remember the wave of relief,” he recalled. Three weeks of waiting, interrupted by one supply flight back over the Hump, still brought no training for Belle Starr’s crew. Finally on the evening of August 23 came word that there’d be an early call the next morning for a mission.

In the dim light of the briefing tent the next morning, they learned that seven B-24s from the 425th Squadron would rendezvous en route with seven more from the 373rd. Then a major said, “They clobbered our friends over Hankow the other day, and we’re going back to show they can’t do that to us!” Another officer announced they were going back to “get those Zeros” that had mauled the 374th and 375th squadrons on the 21st.

Last to speak was the charismatic squadron commander, Major William W. Ellsworth, who had previously impressed the men as a confident leader. My father recalled: “I watched and listened, and suddenly I felt a growing chill—not so much from the words I was hearing but more from growing recognition that this was a very different major than the one I had expected. This was a very uncertain man. His voice shook. His words were slow. The man seemed aged. We were going back to Hankow, and the major was as frightened as I was!”

Oddly, the name Foster came up three times during that briefing. Major Horace Foster, the group operations officer, would fly the lead plane. Captain “Pappy” Foster, the squadron’s intelligence officer, would be waiting at Kweilin, where the flight would land and be debriefed before returning to Kunming. Then Major Ellsworth said: “I’ll fly you, Lieutenant Foster. Meet you at your ship.”

“It should have been a thrill, but this changed man was no longer reassuring,” my dad said. Sheldon Chambers, Belle Starr’s usual co-pilot, would be staying behind that day, and dad moved to the right seat to make way for Major Ellsworth. Ed Uebel, a darkroom technician who had volunteered to take bomb damage photos, would replace assistant engineer Jack Miller for that mission.

Clustered fragmentation bombs were loaded aboard Belle Starr, and long belts of .50-caliber ammo were fed into each gun position. Without any greeting, Ellsworth bounded onto the flight deck, took his place in the left seat and began flicking switches. To dad’s amazement, the squadron commander abruptly started two engines at once, violating normal checklist procedures.

Soon the seven Liberators were roaring down the runway and into the air. The formation slowly climbed and turned left, with Belle Starr on the right, or outside, of the others as one by one they faded into a cloud layer. But when Belle Starr emerged, the other planes were not to its left anymore, but to the right. It had flown through the entire formation in the clouds!

Dad’s uncertainty about Ellsworth increased as they flew on: “He seemed oblivious to me as though absorbed in a world of his own. He wrestled, at times angrily, with the plane, jockeying the throttles back and forth and profanely cursing our plane’s ‘lack of trim.’ In truth, our plane with its belly turret was new to the theater, and it was a heavy addition to the tail, but he seemed to have unusual trouble keeping in formation.” (Much later my father learned that Ellsworth had had a premonition about the mission, telling his roommate that he knew “his number was up.” In an effort to calm Ellsworth, the roommate had shared a bottle of whiskey with him the night before—finally getting the major to bed only about an hour before he had to get up for the briefing.)

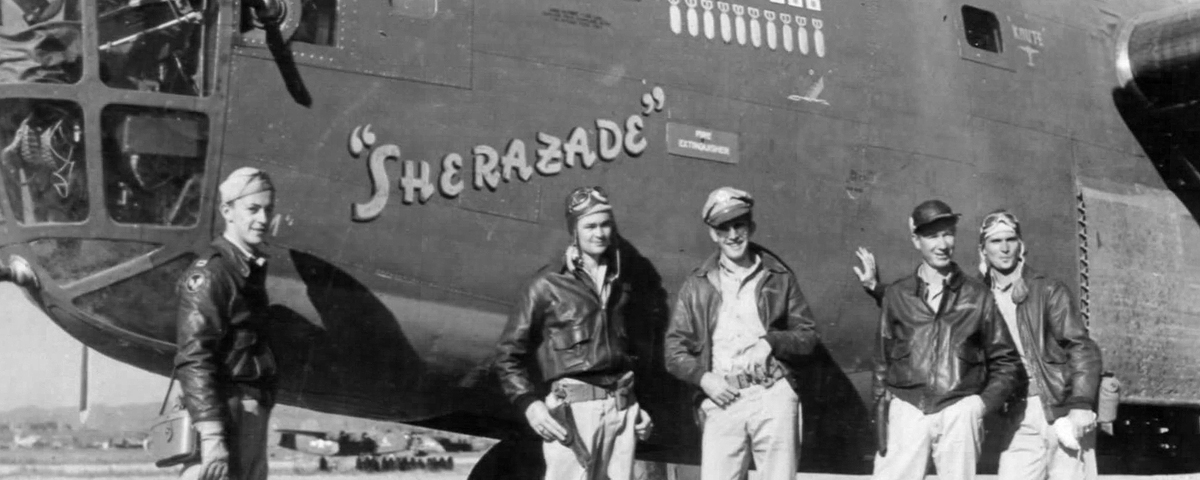

As the bombers flew on, word came over the radio that their sister squadron, the 373rd, would not be joining up—they were fogged in at their base in Yankai. Just as Major Beat had to decide whether to continue without fighter escort or to abort, now Major Horace Foster, leading the formation in Sherazade, had to call the shots. He too decided to continue on.

The weather was beautiful, with bright sun and high cumulus clouds. Feeling rather useless in the right seat, my dad started thinking about Changsha. He wondered whether he would ever see his childhood home and beloved Amah (Chinese for nanny) again.

Suddenly four P-40s appeared off to the right. The pilots of the shark-nosed fighters flew alongside for a bit, saluted, then snaked on ahead. “At least,” thought my dad, “it is reassuring to know the P-40s are out there somewhere.”

Major Foster in Sherazade, leading A Flight, was flanked by new planes and their novice pilots, Lieutenant Clarence Robinson in the unnamed “938” on his left and Lieutenant Linus J. Austin in Star Dust to his right. Leading B Flight in Chug-a-Lug, Captain Leland Farnell (ordered to command that aircraft by Major Foster, who had displaced Farnell in his usual position in Sherazade) had 1st Lt. Joe Hart on his left in Glamour Gal. On the right of B Flight was Belle Starr. Below and behind them was Cabin in the Sky, piloted by 1st Lt. David W. Holder.

After five hours the Liberators approached Hankow and its twin city of Wuchang along the Yangtze River. The bombers lined up on their target, the second of two airfields. Flak started bursting around them, and then the little red light flickered on the pilots’ instrument panel, indicating bombs away. But instead of rapidly turning away from the target, they continued straight ahead, eventually beginning a slow turn to the left. Then came a cry over the intercom: “I see fighters taking off!” Meanwhile, the 30 P-40 and eight P-38 escorts that had been promised were nowhere to be seen.

Off to the right my dad saw a distant airplane paralleling their course. Next he spied a speck straight ahead, heading right at them. Then it grew into another plane, with little “lights” blinking on and off along its wings—a Japanese fighter, firing at them!

Ellsworth gripped the controls tightly, and all dad could do was close his eyes and sink down in his seat. Belle Starr shuddered as its gunners returned fire. The smell of gunpowder permeated the plane. Then came shouting over the interphone—“Get that one!” and so forth, like cheering at a football game.

Robinson’s plane started streaming a trail of gray smoke from its right wing, then dropped out of the formation in a flat spin. Crewmen from other planes said they saw three chutes emerge from 938 before it crashed.

The B-24s had been under attack for some time when my dad heard a popping sound somewhere behind him. Suddenly Ellsworth leaned over and shouted: “Call the lead plane and tell them to slow down. They’ve got a cripple back here!” At first dad thought he meant that Holder was in trouble behind them. Then he saw Ellsworth’s hand thumbing over his shoulder and turned—to face an inferno in the bomb bay.

Three days earlier the lead B-24 had experienced this same sort of fire over Hankow and exploded. Like that plane, all the Liberators on this mission were carrying extra fuel in bomb bay tanks. My dad needed no further instructions. He hit the red bailout button repeatedly.

In the nose, bombardier Jess Young turned from firing his .50-caliber to ask Rosenburg if the alarm was what he thought it was, just in time to see the heels of Rosenburg’s shoes going out the floor escape hatch. Young quickly followed him.

Across the formation, bullets ripped through Glamour Gal’s nose, skimming over the heads of the navigator and bombardier and into the back of the pilot’s instrument panel, setting it afire and sending glass and metal fragments into pilot Lieutenant Hart’s face, temporarily blinding him. Bombardier 2nd Lt. Gordon Ruhf and navigator Lieutenant Fred Scheurman scrambled up to the flight deck. Standing behind Hart and co-pilot 2nd Lt. Clarence B. Stanley, Ruhf put a comforting hand on the co-pilot’s shoulder. Just as he did so, more bullets crashed through the side windows and into Stanley’s chest, killing him. Despite his injuries, Hart managed to dive the bomber and then ordered the crew to bail out.

Major Foster was still leading the small formation in Sherazade, with Lieutenant Donald J. Koshiek in the co-pilot seat. When Sherazade was raked by cannon fire in its bomb bay, right wing and rear fuselage, the No. 3 engine oil tank was punctured, and fuel began pouring from a broken line in the bomb bay.

Then things got even worse, as Koshiek later explained: “A 20mm shell entered the cockpit in front of me and exploded at Major Foster’s head. My face was full of plexiglass and shell fragments, and the shock of the shell knocked me out. I came to in time to take the plane out of a stall.”

In Chug-a-Lug’s nose, bombardier Lieutenant Elmond J. Purkey watched a fighter coming right at him. A shell exploded at his feet, and shrapnel peppered his legs. Substitute tail gunner Staff Sgt. Louis Kne was hit and killed instantly, and four other crewmen were seriously wounded. Co-pilot John White headed to the back of the plane to administer first aid, saving two of the gunners. White subsequently manned first one and then the other waist .50s until the ammo ran out. Chug-a-Lug had more than 200 holes from cannon and machine gun fire by the time Captain Farnell flew into cloud cover and turned south, headed home.

As the attack continued, the Japanese turned their attention to the trailing plane, Cabin in the Sky, piloted by Lieutenant Holder and co-pilot 2nd Lt. George E. Mosall. The B-24 was soon riddled with holes, and both engines on the left were knocked out. Even with full power on Nos. 3 and 4, it couldn’t keep up with the formation. No guns were firing, and Holder and Mosall got no response from the nose or tail. When they were only a thousand feet up, they agreed it was time to get out. But to their horror, as the two teetered on the narrow catwalk near the bomb bay, they saw the engineer, Staff Sgt. William Spells, staring at them from the far hatchway—without a parachute. The plane then rolled to one side, and Holder and Mosall dropped out. They landed safely, but they never forgot the look on Spells’ face.

Back in Belle Starr there was a crisis in front and rear. Bail-out procedures had seemed obvious during training. But figuring out how to follow those procedures was a different matter when Belle’s bomb bay was a holocaust, and flames were also streaming from the right wing and engine No. 3.

Dad leapt up and unlatched the small hatch above the engineer’s position, then pulled himself up into the 200-mph wind—and his seat parachute caught on the lip of the opening. He struggled for a few minutes, then fell back into the cockpit, exhausted. Sitting there, he was vaguely aware of Bill Gieseke dropping down from the upper gun turret. When dad tried once again to get through the hatch, he felt Gieseke’s hand on his left heel, pushing hard enough to pop him through the opening. “I know I laughed out there in space,” he said. Starting his free fall from 18,000 feet, he delayed opening his parachute and landed with only a broken rib to show for his brush with combat.

Gieseke, wearing a chest-pack type chute, had an easier time exiting the plane. But then he made a crucial error, opening his chute immediately. A fighter made several passes at him, shooting off half of one foot as he floated down.

Belle Starr’s waist gunners had watched a hole appear behind the No. 3 engine and a long streamer of flames flowing back toward them. Then they saw the hit to the bomb bay, followed by a roaring fire. The two gunners, Pannelle and Smith, were working frantically with tail gunner Ray Reed to extract Hutchinson from inside the ball turret. Uebel stood waiting to jump with the others. They were snapping Hutchinson’s chest-pack parachute to his harness when “Suddenly everything turned red,” Pannelle recalled. The right wing broke off, and the bomber went into a tight spiral. Centrifugal force threw Pannelle out one of the open waist windows and Uebel out the other. The other gunners died when Belle Starr hit the ground. Also left aboard was Ellsworth—still at the controls when Gieseke and dad last saw him.

Chinese guerrillas collected the downed fliers near the village of Hsiung Chian Tung and, carrying Gieseke on an improvised stretcher, managed to evade Japanese searchers. Eventually the party would number 11 survivors of the Hankow raid: dad, Rosenburg, Young, Pannelle, Uebel, Hart, Ruhf, Scheurman (navigator of Glamour Gal), Solberg (Glamour Gal’s engineer), Holder and Mosall. Gieseke died of his injuries a day after the mission.

Chug-a-Lug, riddled with holes, had escaped via that fortuitous cloud. Flying on a compass heading that navigator Lieutenant Irwin Zaetz provided from memory (his maps had blown out of the shattered nose), it headed straight back to Kweilin. Captain Farnell told the wounded crewmen they could bail out over the field rather than risk landing. They all decided to ride it down. Farnell landed without flaps, at 150 mph. He later explained, “With all the damage that plane had had, I was going to make sure it didn’t quit flying until I got her on the ground!” Without brakes, and given all that speed, he ground-looped at the far end of the runway, spinning the bomber around and around until it came to a stop neatly in the parking area.

Sherazade had its own problems but was still flying. Bombardier Morton Salk climbed up to the flight deck, helped to remove Major Foster’s body from the left seat and sat down to help Koshiek fly the plane. But then they got lost. After three long hours navigator Charles Haynes eventually got them on course to Hengyang. They too landed without brakes, managing to stop at the end of the runway. But Hengyang was too close to the Japanese for comfort. Frantic work patched up Sherazade’s fuel and hydraulic lines, at least sufficiently for the crew to fly back to Kunming the next morning.

Star Dust, piloted by Lieutenant Austin, landed at Kweilin without apparent damage and was scheduled to return to Kunming the next morning. “Pappy” Foster, on hand to debrief the returning crews, decided to return with Star Dust. The bomber took off normally, and Austin called Kunming when they were 40 minutes away from landing. Shortly after that, Star Dust flew into a mountaintop. Miraculously, two sergeants were thrown from the plane and survived.

In the end, only one of seven B-24s that left Kunming that morning returned to its base. Of the 73 men present at that early morning briefing, just 12 returned to base on August 25. Fifty men had died (31 at the scene of the battle), and then there were the 11 who were walking back.

For 10 strenuous days dad and the others were escorted through the country, mostly on foot—up and down mountains, across rice paddies, through villages and hiding in secret camps. During most of the journey the Americans had no idea where the Chinese were taking them, but eventually they learned their destination: Changsha, my father’s childhood home.

When they arrived, a small party of Westerners was waiting to greet them. An Englishman walked up to dad and said, “My name is John Foster.” “That’s my name too,” said my father. The Brit was John Norman Foster, a Methodist minister who worked for the Red Cross. When the fliers were assigned billets, dad chose a house across the street from the home where he had lived as a boy.

Nine fliers were invited to lunch the following day by Ethel Davis, another Methodist missionary. As they introduced themselves, Davis exclaimed “Johnny!” and hugged my very surprised father. She had known his family during the 1920s. After lunch she announced, “If the rest of you wouldn’t mind returning to the living room, I have a surprise for Johnny.” She then went into the kitchen and returned with a weeping Chinese woman. My father was at first stunned, but then he too began to cry—this was his Amah! With Davis translating, they spent an hour catching up on family news.

The next day brought a ceremony with speeches and gifts for the “American air generals,” a noisy parade and an elaborate banquet. But before the fliers began eating, an Army sergeant went to each man and whispered that Japanese infiltrators were rumored to be in Changsha. They would have to leave immediately. One by one the Americans rose and slipped out the back door, where rickshaws waited to take them to a boat.

Thus for the second time in his life dad surreptitiously exited Changsha by riverboat. As an evadee he was required to go back to the States, where he spent the rest of the war.

The August 24 Hankow raid represents just one mission in one theater of a global war. Yet it embodies the universal story of American volunteers thrust into combat. As for my father, John T. Foster, his experience with China had come full circle—and he had lived to tell about it.

Alan Foster is the younger of two sons of the late U.S. Air Force Major John T. Foster, who lived until 2003 and self-published an account of his experiences, China Up and Down. Additional reading: Chennault’s Forgotten Warriors: The Saga of the 308th Bomb Group in China, by Carroll V. Glines; or B-24 Liberator Units of the Pacific War, by Robert F. Dorr.

This article by Alan Foster was originally published in the January 2008 issue of Aviation History Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!