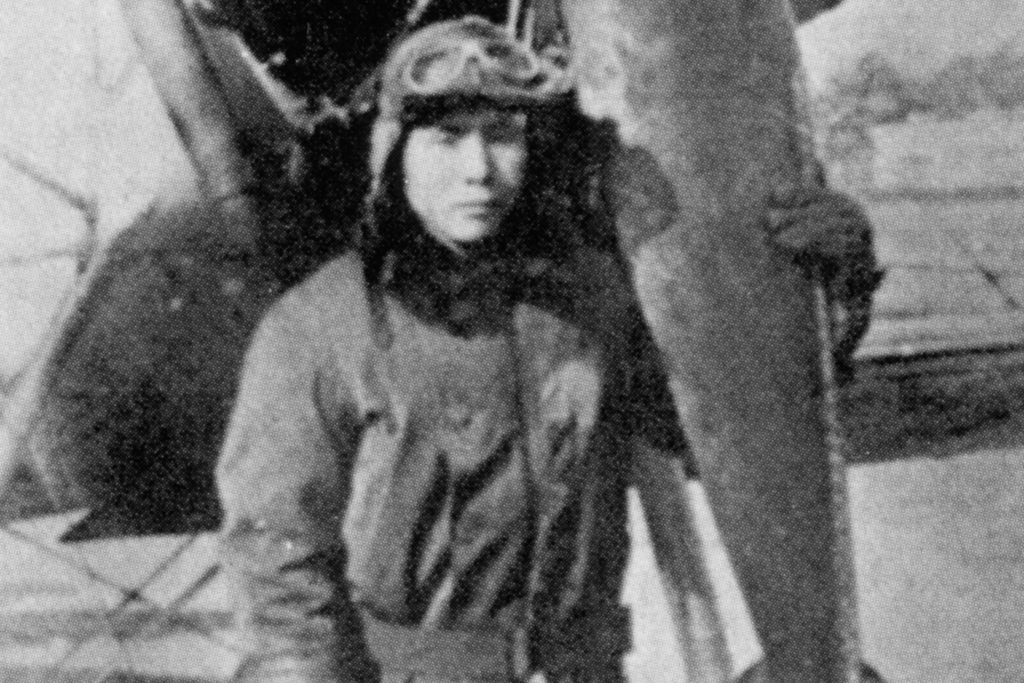

Early in the afternoon of December 7, 1941, 21-year-old Airman First Class Shigenori Nishikaichi nursed his crippled Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter west from Oahu. Nishikaichi had taken off from the carrier Hiryu in the second wave of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, but a bullet-punctured fuel tank barred his return. He was forced to land on Niihau, a small, isolated island about 150 miles from Oahu.

Nishikaichi’s choice of Niihau was not random. The Japanese Imperial Navy wrongly believed the island was uninhabited and had designated it as an emergency landing site. They arranged for a submarine, the I-74, to stand by for rescue work—but then ordered the submarine away prematurely.

The events that followed the pilot’s rough landing on this remote island—events including threats, bribes, and violence—would seem curious by any measure. But stranger still was that these occurrences, far from being a mere colorful historical footnote, played a role in the eventual evacuation and infamous internment of more than 100,000 Japanese Americans in the tumultuous weeks and months after Pearl Harbor.

In December 1941, Niihau’s only contact with the outside world was a weekly visit by boat. Approximately 182 Hawaiians called the island home, but three adults of Japanese descent also lived there. Sixty-year-old Ishimatsu Shintani was an issei—a Japanese immigrant to the United States—who had spent most of his life in Hawaii. The other two were Yoshio Harada, 38, and his wife, Irene. The Haradas were Nisei, second-generation individuals of Japanese descent, born in Hawaii. By American law, the Haradas were American citizens; Shintani was an alien.

It was one of the island’s native Hawaiians, a man named Hawila Kaleohano, who first approached Nishikaichi’s plane, which he recognized as Japanese. Kaleohano knew of the recent tense relations between the United States and Japan, but nothing of the Pearl Harbor attack. The landing had left Nishikaichi temporarily stunned, and Kaleohano alertly grabbed the pilot’s pistol and a set of papers with sensitive information such as attack details and radio codes. He then summoned two of the island’s Japanese-speaking residents, Shintani and Yoshio Harada, to act as interpreters. After a brief discussion with the pilot, Shintani departed, apparently to disavow by his absence any relationship with the aviator or his country. The pilot then reluctantly disclosed news of the attack to Harada—who did not share the information with his neighbors.

At first the islanders treated the pilot as an unexpected guest, but his status abruptly changed that night when the Hawaiians learned via a battery-powered radio of the attack on Pearl Harbor. They placed Nishikaichi under loose guard in anticipation of the weekly boat’s arrival the next day, Monday, December 8. But the boat did not come—American authorities had forbidden such trips. Nor did it come during the next four days.

The American-born Harada persuaded the Hawaiians to leave Nishikaichi with his family, with five Hawaiians to act as guards. On Friday Harada and Nishikaichi enlisted Shintani’s help again, dispatching him to Kaleohano’s house, where he offered Kaleohano 200 dollars—a gigantic bribe by Niihau standards—to return the pilot’s papers. He pleaded that Nishikaichi had threatened to kill him if he failed; when Kaleohano refused, the terrified Shintani went into hiding.

The Haradas proved more useful to the Japanese pilot. While Irene Harada played loud music as a distraction, Nishikaichi and Yoshio Harada overpowered the guard on duty. Using Nishikaichi’s pistol and a shotgun Harada had stolen earlier that day, the two men launched a miniature reign of terror in a desperate endeavor to recover the missing papers. They threatened to kill the nearby villagers, took hostages, and then released them to track down Kaleohano. But Kaleohano eluded them and, with five other islanders, secretly set out in a rowboat for nearby Kauai to summon help.

During their rampage, Nishikaichi and Harada set fire to the Zero, and to Kaleohano’s home when they couldn’t find the papers there. On the morning of Saturday, December 13, the two of them captured a rancher, Ben Kanahele, and his wife, Ella. They held Ella hostage and sent Kanahele, a man locally known for his strength and his height—he was six feet tall—to retrieve the missing Kaleohano. Kanahele knew Kaleohano was on his way to Kauai, so he feigned a search and then returned, concerned for his wife’s safety.

He begged Harada to take the aviator’s gun, but Harada replied that if he did, he would be killed. So Ben Kanahele took matters into his own hands. Catching the pilot momentarily off-guard, he and his wife jumped him. Harada pulled Ella away from the struggle; Nishikaichi ripped an arm free and shot Kanahele three times. The Hawaiian’s physical wounds were superficial—but the emotional wound was not. “I got mad,” Kanahele laconically reported. The big Hawaiian grabbed the diminutive pilot and dashed his head against a stone wall. Ella smashed a rock against the pilot’s skull, and Ben finished him with a knife. The “battle of Niihau” ended when Harada fatally wounded himself with the shotgun. In ways that few could have envisioned, however, the Niihau incident would reverberate from Hawaii to the highest office in the land.

On February 19, 1942, president Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Under this authority, the army uprooted from their homes 119,803 men, women, and children of Japanese descent, aliens and citizens alike, and transported them to hastily built camps in the nation’s interior. Besides bewilderment and shame, most internees experienced severe economic losses involving their homes, their businesses, and their employment. The episode remains a huge blot on the nation’s record in World War II.

The path from Pearl Harbor to Executive Order 9066 is often imagined as a crude story of public hysteria ignited immediately after the attack that soared inexorably to a peak in February 1942. But that was not the case. After the war, scholar Morton Grodzins studied 112 California newspapers dated from December 8, 1941, to March 8, 1942. He classified opinion articles, readers’ comments, and news articles as either favorable or unfavorable to Japanese Americans. The comments ultimately totaled 105.5 favorable to 163.5 unfavorable. Grodzins noticed that their timing was crucial, however. Prior to the week of January 26, 1942, favorable comments outnumbered unfavorable comments by a ratio of 10 to 1. But beginning the week of January 26, 1942, that dramatically reversed.

That week the war news remained grim—but no grimmer than at any point since Pearl Harbor. Stories and rumors questioning the loyalty of Japanese Americans had actually diminished. But, judging by their subsequent actions, local and national elected officials in California had no doubt about the trigger for this stunning shift: the publication of the Roberts Commission Report.

One week after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt appointed a commission to respond to the public outcry for an accounting for the disaster—and to head off a potentially divisive congressional inquiry. The head of the commission was Supreme Court associate justice Owen J. Roberts, a Republican appointee who had investigated both the spectacularly successful Black Tom German sabotage attack in World War I and the Teapot Dome scandal. The four other members were army generals Frank R. McCoy and Joseph T. McNarney, and navy admirals William H. Standley and Joseph M. Reeves.

Roosevelt directed the group, which became known as the Roberts Commission, to determine responsibility for the disaster and ascertain whether there was any dereliction of duty or errors of judgment. Beginning on December 17, 1941, the commission heard 127 witnesses, took 1,887 pages of testimony, and gathered over 3,000 pages of documents.

Its findings were released on January 23, 1942. The commission absolved leaders in Washington of any serious fault in the disaster. Instead, it unjustly heaped virtually all the blame on the two commanders in Hawaii, Adm. Husband E. Kimmel, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and Lt. Gen. Walter Short, commander of the army’s Hawaiian Department. The commission’s report found them guilty of the extremely onerous charge of dereliction of duty, a finding that not only triggers court-martial proceedings, but also suggests a disgraceful neglect of responsibilities.

Less definitive, but with far-reaching implications, were the commission’s comments—and Justice Roberts’s private beliefs—on Japanese American loyalty.

The issue of disloyal segments of the population was not novel in American history, with examples dating back to the American Revolution. But in 1941 the American lexicon had acquired a new term, “fifth column”—which stemmed from an episode in the Spanish civil war—to describe citizens of any nation who became agents of espionage, subversion, or sabotage against that nation. During Hitler’s parade of triumphs in western Europe, a series of real episodes and grossly exaggerated hearsay gave meaty substance to fears that subversives who might strike on behalf of the Axis powers were everywhere.

In the United States, the issue of fifth-column activities had emerged well before Pearl Harbor, during the bitter struggle between those who favored intervention on behalf of Great Britain and those who opposed it. Leaders of the isolationists charged Roosevelt with dictatorial aspirations. Roosevelt in turn flatly described isolationist leaders as “Fifth Columnist appeasers.” Administration figures goaded the FBI and Treasury Department to find evidence to support their belief that foreign direction and funding was behind the opposition to intervention. Meanwhile, actual Soviet spies had penetrated top positions in the administration, but were ineffectually and haphazardly pursued.

The issue of Japanese American loyalty after Pearl Harbor arose, therefore, in an already charged atmosphere. Add to that a powerful current of pure racism, and the clout of the economic competitors of Japanese Americans—who would instantly benefit from their elimination—and their mass evacuation would quickly come to be seen as a desirable option.

The commission had solid reasons to doubt the loyalty of at least some individuals in the United States with ties to Japan. As Admiral Kimmel, General Short, and other officers pointed out, documents taken from downed Japanese planes and a captured midget submarine revealed very accurate and detailed knowledge about American installations and the exact locations of ships in the harbor. It was beyond dispute that the work of Japanese spies had greatly facilitated the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The obvious source of the intelligence was the Japanese consulate in Honolulu, which had designated over 200 individuals of Japanese descent in Hawaii as consular agents. The commission learned of a torrent of intercepted coded messages flowing from the consulate to Tokyo. The head of the U.S. Navy’s counterespionage effort in Hawaii, Capt. Irving Mayfield, told the commission he believed the Japanese consulate knew of the espionage activities, but that the Japanese had partitioned their espionage apparatus from direct contact with the consulate. As it turns out, he was wrong: the espionage that supported the attack was, in fact, conducted from the consulate, particularly by Takeo Yoshikawa, a former ensign in the Japanese Imperial Navy.

Over four critical days, from January 5 to January 8, the commission gathered reams of testimony on the loyalty of Japanese aliens and citizens. Leading off was a diverse array of civilian witnesses, including the mayor of Honolulu and a University of Hawaii professor. All of them affirmed the loyalty of Japanese American citizens and resident aliens. They deemed that only a distinct minority of either category posed any threat. Buttressing the civilians was the eloquent testimony of Briant H. Wells, a retired army major general and former commander of the Hawaiian Department. Wells denounced stories of disloyalty, much less sabotage. “Our whole country is made up of people from all races,” he barked. “And one citizen is just as good as another citizen as far as rights are concerned.” Then he made a telling observation: “I cannot imagine a more favorable opportunity for sabotage than that which was here on December 7th and nothing happened.”

The territorial governor of Hawaii, Joseph B. Poindexter, was more measured. He provided statistics indicating that 34 percent of the islands’ population were aliens, or citizens of Japanese descent. Poindexter expected a “great many” Japanese Americans to be loyal. He said while there had not been “much evidence” of sabotage, this might be because of the martial law regime and the fear it engendered. One of the commission members, Admiral Standley, suggested that the absence of sabotage so far could be an indication the potential saboteurs were merely biding their time, but Poindexter insisted only “a few individuals” presented any danger.

Poindexter did, however, volunteer an unsettling comment. “You see, we have a great population of Japanese that have never been put to the test,” he told the commission. “We don’t know how they are going to react. One man’s opinion is just as good as another’s as far as what is going to happen so far as they are concerned. My opinion is that most of these young Japanese want to be loyal to the United States. I am not certain of all of them, and I am very certain that the old people still cling to Japan.”

The tide of emphatically—or at least cautiously—affirmative or mixed testimony on the loyalty of Japanese Americans ceased with the appearance of Angus M. Taylor, the United States attorney for Hawaii—and it was then that the incident at Niihau ballooned into significance. Taylor minced no words: those of Japanese blood would join Japan’s armed forces in an invasion. And Taylor knew the importance of buttressing argument with supporting facts. “The incident at Niihau should have convinced anyone if they needed convincing,” he insisted, “because [the Japanese Americans] went right over to help that aviator.”

Another civilian witness, Richard K. Kimball, told the commission that Japanese Americans would be loyal so long as it looked like the United States was “on top.” Very few, however, would “remain loyal long enough to go down fighting for the American flag—very few.” Kimball specifically cited the Niihau incident to support his opinion. With their attention obviously now drawn to the episode, the commission asked the very next witness, Lt. George Kimball, if he had personal knowledge of the Niihau incident. Lieutenant Kimball explained he lacked personal information, but recited the events as relayed to him in a report.

In addition to testimony, the Roberts Commission included accounts of the Niihau incident in its document collection. Among these was a report prepared for the 14th Naval District Intelligence Office on January 26, 1942. It concluded that the episode on Niihau “indicates likelihood that Japanese residents previously believed loyal to the United States may aid Japan if further Japanese attacks appear successful.”

The Roberts Commission Report was released to the public on January 24, 1942. In pertinent part, it proclaimed:

The commission heard much testimony as to the population of Hawaii, its composition and the attitude and disposition of the persons composing it, in the belief that the facts disclosed might aid in appraising the result of the investigative, counterespionage and anti sabotage work done antecedent to the attack of December 7, 1941.

And:

There were, prior to December 7, 1941, Japanese spies on the island of Oahu. Some were Japanese consular agents and others were persons having no open relations with the Japanese Foreign Service. The spies collected and, through various channels transmitted, information to the Japanese Empire respecting the military and naval establishments and dispositions on the island.

The effect of the report proved dramatic—and decisive. Before January 24, 1942, hysteria, racism, and even concrete evidence of individual acts of disloyalty, gathered in prewar raids on Japanese intelligence officers and via radio intelligence, had not propelled government policy to mass evacuation. The U.S. Army and the Department of Justice supported a plan to designate a number of specific sites on the West Coast as sensitive areas—aircraft manufacturing plants and shipyards, for example—and evacuate aliens from those areas. But that plan would have affected only 7,000 aliens, including fewer than 3,000 Japanese.

Only days after the release of the report, however, all that had changed. When Gen. John L. DeWitt, the key army commander on the West Coast, met with California governor Culbert L. Olson on January 27, Olson told DeWitt that there was now tremendous public demand to remove all Japanese, aliens and citizens. Olson explained, “Since the publication of the Roberts Commission Report [the people of California] feel that they are living in the midst of a lot of enemies. They don’t trust the Japanese, none of them.” Two days later, California attorney general Earl Warren endorsed mass evacuation. The capitulation of key civilian authorities who had previously resisted mass evacuation put an end to DeWitt’s indecision. On January 31, he endorsed mass evacuation. Just 11 days later, mass evacuation became official policy.

What seems strange in light of the shift in official and public opinion is that the commission’s report employed remarkably innocuous language, never directly affirming the loyalty or condemning the alleged disloyalty of Japanese Americans. When the report identified the source of espionage as not just “Japanese consular agents” but also other persons “having no open relations with the Japanese Foreign Service,” citizens, elected officials, and military officials interpreted this as meaning persons of Japanese descent.

Influential though the Roberts Commission Report was, the strongest influence may have come from Roberts himself. The Supreme Court justice met with secretary of war Henry L. Stimson on January 20, 1942, and Stimson’s diary provides an important insight into Roberts’s views. According to Stimson, “The tremendous Japanese population in the island [Roberts] regarded as a great menace particularly as a large portion of them are now armed under the draft.” Roberts also told Stimson that he did not think the FBI had “gotten under the crust of their secret thoughts,” and so their real thinking was unknown. He added that the “great mass of Japanese, both aliens and Americanized, existed as a potential danger in the islands in case a pinch came to our fortunes.”

Roberts also met with Roosevelt on January 18 and January 24. There is no exact record of their conversation, but it is reasonable to assume it covered the same ground. What is known is that Roosevelt effectively delegated the final decision on evacuation and internment to Stimson. And while Stimson opposed mass evacuation prior to his talk with Roberts, after that talk, and after the shift in public opinion on the West Coast and the altered stance of senior state officials and General DeWitt, Stimson ultimately advocated the mass evacuation that resulted in Executive Order 9066.

While the incident at Niihau did not lead inexorably to the evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans, it clearly exerted an insidious influence by appearing to provide heft to the testimony of witnesses before the Roberts Commission who disparaged the loyalty of persons of Japanese descent.

For seven weeks following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the balance of opinion tilted against mass evacuation of persons of Japanese descent. The Roberts Commission Report represented the tipping point. But the report did not achieve this effect by directly endorsing fears of actual or potential disloyalty of all such persons. Rather, it failed to affirm a presumption of loyalty of persons of Japanese ancestry—an omission that the public and leaders interpreted as indicating that such persons were real or potential fifth columnists. As the proceedings behind the report demonstrate, the commission received powerful evidence on both sides of the loyalty issue. The commission also heard that it was a matter on which opinions differed, and could only be settled by an actual test. The Niihau incident presented one concrete test with a dreadful result.

Which brings us to a final lesson about the long-term significance of the battle of Niihau: anecdotal evidence, such as that posited here on Niihau’s significance and the “evidence” of loyalty considered by the commission, should be approached with only the utmost caution. Begging the question: would history have taken a different path had the Japanese American Haradas proven inhospitable to Nishikaichi?

What is indisputable is that the battle of Niihau produced a genuine American hero, and enjoyed an interesting cultural afterlife. The U.S. Army decorated Ben Kanahele with a Purple Heart medal for wounds and a meritorious service medal. (It is arguable that Ella Kanahele deserved a medal also since she and her husband both attacked two armed men while weaponless, save for Ben’s knife.) Hawaiian composer R. Alex Anderson wrote the popular wartime ditty, “They Couldn’t Take Niihau No-How.” For years after the war television host Arthur Godfrey kept the song alive, thanks to his huge following.

Particularly remarkable is that when the mass evacuation of Japanese Americans that Justice Roberts had done so much to cause came for review before the Supreme Court in December 1944, he vehemently dissented from the decision upholding the action. His about-face may have reflected yet another facet of the Niihau story. Just as the “battle” ended, a boatload of soldiers—led by a Japanese American, Lt. Jack Mizuha—reached Niihau. Mizuha would later serve in a storied Japanese American unit in Italy, where he was severely wounded. Still later he would become the first attorney general of the new state of Hawaii—and eventually a justice on the state’s Supreme Court.

Two of the other key players in the incident, Ishimatsu Shintani and Irene Harada, were arrested shortly afterward. Shintani was sent to an internment camp on the mainland, while Harada, an American citizen, was held under rough conditions of confinement for nearly three years. Upon release, Shintani returned to his family in Niihau; he became a naturalized American citizen in November 1960. Harada, destitute, set up a dress shop on Kauai and gradually regained her footing. In Japan, the episode became increasingly celebrated following the war, including a dramatization on the national television network, with Harada as its narrator and heroine.

In the Japanese hometown of pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi, a memorial was erected in his honor. The Zero he flew is now on display at Hawaii’s Ford Island. Few who gaze on this relic imagine it was part of a story far broader than its few minutes over Pearl Harbor.

Richard B. Frank is the author of Guadalcanal and Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire, and worked on the HBO miniseries The Pacific. In 2006, his work MacArthur appeared as part of the Palgrave Great Generals series. He has appeared many times on or consulted for programs on television and radio, including ABC, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the BBC, NPR, and the History Channel. He is currently working on a narrative history trilogy about the Asian-Pacific war.

This article originally appeared in the July 2009 issue of World War II magazine.