During the Vietnam War, there was a compulsory draft of American physicians. One of the few alternatives to service in Vietnam was a position in the Public Health Service. The limited number of such appointments made them highly competitive—especially for doctors who wanted to join the clinical associate program at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Successful candidates, sometimes derogatorily described as “Yellow Berets,” trained there under leading laboratory scientists and provided care to patients at the campus research hospital. Among the roughly 200 trainees who entered the clinical associate program in 1968, four physicians with little or no prior research experience—Joseph Goldstein, Michael Brown, Harold Varmus, and Robert Lefkowitz—went on to distinguished careers crowned by Nobel Prizes, the highest honor in science. Medal Winners: How the Vietnam War Launched Nobel Careers explores the NIH clinical associates program and its impact on science and medicine through the work of these four brilliant investigators and their NIH mentors.

During the Vietnam War, there was a compulsory draft of American physicians. One of the few alternatives to service in Vietnam was a position in the Public Health Service. The limited number of such appointments made them highly competitive—especially for doctors who wanted to join the clinical associate program at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Successful candidates, sometimes derogatorily described as “Yellow Berets,” trained there under leading laboratory scientists and provided care to patients at the campus research hospital. Among the roughly 200 trainees who entered the clinical associate program in 1968, four physicians with little or no prior research experience—Joseph Goldstein, Michael Brown, Harold Varmus, and Robert Lefkowitz—went on to distinguished careers crowned by Nobel Prizes, the highest honor in science. Medal Winners: How the Vietnam War Launched Nobel Careers explores the NIH clinical associates program and its impact on science and medicine through the work of these four brilliant investigators and their NIH mentors.

The connection between the Vietnam War and the rise of the NIH associate program was undeniable. Clearly, many of the trainees were motivated to apply because of the “doctor draft.” If they had reservations about serving in the war effort, they were hardly alone, as many others managed to find alternative forms of service. Some drew attention decades later when they were elected to high national office. These include Vice President Dan Quayle, who joined the Indiana National Guard, President George W. Bush, who was in the Texas Air National Guard, and President Bill Clinton, who signed up for a reserve officer program before receiving a high lottery draft number that assured he would not be drafted.

It was understandable that a pathway to nonmilitary service through the Public Health Service would be viewed with some antipathy by military physicians. A former NIH associate and later president of the American Board of Internal Medicine, Harry Kimball, observed: “We were doing our service obligation in a way which also was maximally enhancing our own careers. Why wouldn’t they [military physicians] resent us?”

Whether or not such resentment ran deep, Public Health Service trainees became known as “Yellow Berets.” It is unclear where this epithet originated, but supporters of the war in Vietnam applied it generally to anyone they felt was shirking a patriotic duty. In 1966, singer-songwriter Bob Seger composed the “Ballad of the Yellow Beret” with the following lyrics:

Fearless cowards of the USA

Bravely here at home they stay

They watched their friends get shipped away

The draft dodgers of the Yellow Beret.

The “Yellow” Beret denigration contrasted, of course, with the public’s view of the Green Berets, members of the U.S. Army Special Forces. Green Berets were celebrated in a different 1966 song, “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” written by Staff Sgt. Barry Sadler and novelist Robin Moore. The song opens with these lyrics:

Fighting soldiers from the sky

Fearless men who jump and die

Men who mean just what they say

The brave men of the Green Beret.

“The Ballad of the Green Berets” was No. 1 in the United States for five consecutive weeks, with more than 9 million copies sold. A year earlier, Moore had published a bestselling novel titled The Green Berets. An action movie of the same name, loosely adapted from the novel, was produced and directed by John Wayne, who cast himself in the leading role. The movie was released in the United States in the summer of 1968. Although the movie made a profit, it was panned by New York Times critic Renata Adler as “so unspeakable, so stupid, so rotten and false in every detail.” (By then Seger changed his tune. In January 1968, he released an anti-

war song, “2+2=?.”)

Although Public Health Service associates may have been far away from actual combat, they were not far away from military physicians. Directly across from the front entrance of the NIH on the east side of Bethesda’s Rockville Pike is the former National Naval Medical Center (known since 2011 as the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center). President Franklin D. Roosevelt had selected the site of the Naval Medical Center and participated in the laying of its cornerstone on Nov. 11, 1940. This facility, which originally served wounded sailors and Marines and now also serves the Army and Air Force, expanded over time and contained more than 1,100 hospital beds during the Vietnam years.

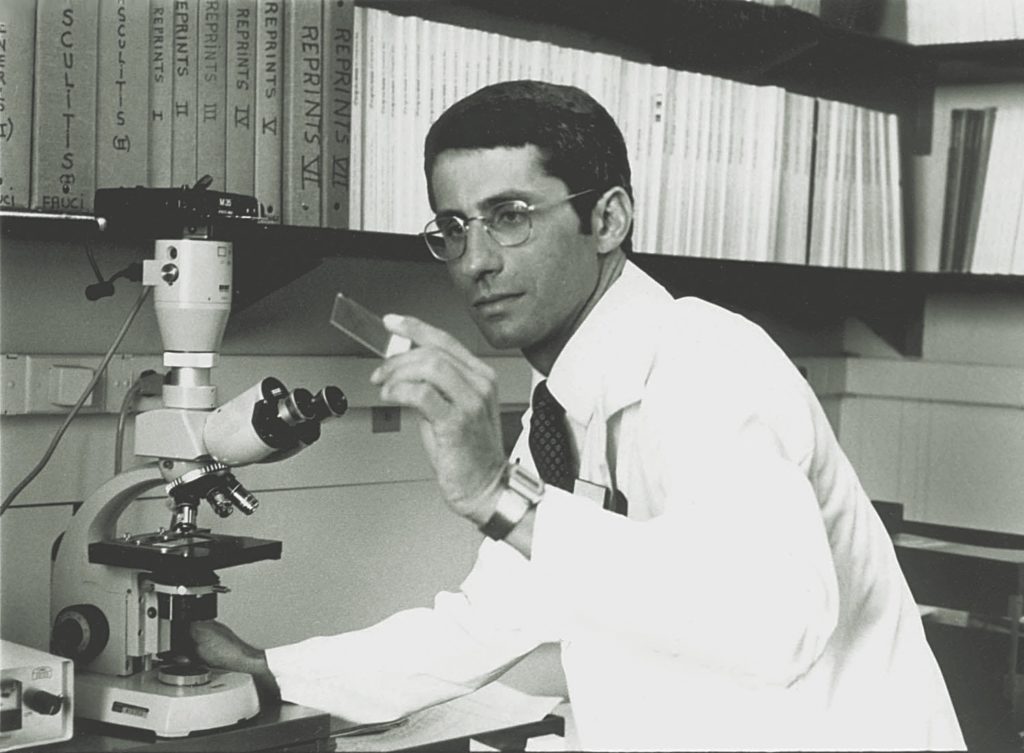

Anthony Fauci, former clinical associate and later the long-serving director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, acknowledged that during the Vietnam War the military doctors on the other side of Rockville Pike did not always view the NIH associates positively. “There was in fact a general feeling of some slight resentment about physicians who did not go into the service but who were here at the ‘cushy’ job at the NIH,” he said.

There were exceptions, Fauci noted. His boss at the time, Dr. Sheldon Wolff, formed the first Infectious Diseases Consultation Service because the Naval Medical Center did not have an infectious disease department at the time. Fauci felt that volunteering “to help with the workload of troops who were flown in with serious infectious complications of wounds sort of put us in a soft spot in their [Navy doctors’] heart. The infectious disease crew was well thought of by the Navy as opposed to some of the others.”

If tensions existed, they likely were fueled by the perception that NIH faculty and staff tended to oppose the war. “In general, the spirit on campus was much more a liberal leaning than a conservative leaning because that is generally the case with scientists,” Fauci said. “Most people were against the war.”

Former associate Kimball participated in an anti-war protest outside the NIH administration building. “I suspect that if you look at it in that time ’67 and ’68, the bulk of investigators at the NIH would not have favored [President Lyndon B.] Johnson’s Vietnam policies,” he said. Donald Fredrickson, a former NIH director, said, “This was a group of people that had liberal politics in the main. There were very few conservatives in those days.” Many of the clinical associates had strong moral objections to the Vietnam War, above and beyond their political leanings.

Leaders of the anti-war efforts at the NIH included Christian Anfinsen, who headed the Laboratory of Chemical Biology at what would become the National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease. Anfinsen, awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1972, was politically active in a number of causes. He participated in a 1964 vigil held on the NIH campus after Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which authorized Johnson to send combat troops to Vietnam. Anfinsen believed in peaceful protests and referred to himself as a professional petitioner and letter-signer.

A small group of activists at the NIH and its sister center at the Public Health Service, the National Institute for Mental Health, organized the Vietnam Moratorium Committee at NIH-NIMH. The moratorium committee included a cross-section of personnel, from senior scientists to trainees and support staff. The group met for the first time on Sept. 23, 1969, in Building 2, a laboratory research facility on the NIH campus. Its members wanted to invite Dr. Benjamin Spock, a nationally prominent pediatrician and leading critic of the Vietnam War, to speak at the NIH. The intended day for his talk was Oct. 15, the scheduled date for an anti-war protest called the National Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam.

The National Moratorium evolved from an original target of 300 colleges into a much broader protest, with a focus on events in Washington. The NIH-NIMH Vietnam Moratorium Committee’s invitation to Spock was endorsed by the Interassembly of Scientists, the NIH’s elected council of staff scientists. Spock accepted the invitation the following day, and the Vietnam Moratorium Committee asked for permission to use the Clinical Center’s auditorium to host the event. On Sept. 29, NIH Director Robert Q. Marston denied the request, likely because he was directed to do so by his politically appointed bosses at the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

The American Civil Liberties Union represented the Vietnam Moratorium Committee in a legal challenge to Marston’s decision. The case was heard in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on Oct. 10. The presiding judge, John Sirica, later earned national fame for his 1973 order that forced the White House to release President Richard Nixon’s secret tape recordings. In the Spock speech case, Sirica ruled against the moratorium committee, but on Oct. 14 a three-judge appeals panel overturned the decision.

The following day, the 66-year-old Spock, looking grandfatherly with large, heavy framed eyeglasses, thinning wisps of white hair, a slightly rumpled dark suit and narrow tie, appeared on the NIH campus. Spock addressed a crowd of several thousand people who had assembled on the lawn in front of the administration building.

There was great symbolism in the site chosen for Spock. It was Building 1, the first building constructed at NIH, in 1938. The pediatrician stood between two towering, white Ionic columns on the front portico of the red brick Georgian Revival-style building in exactly the same spot where, nearly three decades earlier, FDR had appeared. The president had come to Bethesda on Oct. 31, 1940, to dedicate the initial six buildings of the NIH.

About four months earlier, France had fallen to the Germans and the United States was still five months away from coming to Britain’s aid through the lend-lease program. With war looming, Roosevelt searched for a silver lining: “All of us are grateful that we in the United States can still turn our thoughts and our attention to those institutions of our country which symbolize peace—institutions whose purpose is to save life and not to destroy it.”

The president continued: “The National Institute of Health speaks the universal language of humanitarianism. . . . The total defense that we have heard so much about of late, which this nation seeks, involves a great deal more than building airplanes, ships, guns and bombs. We cannot be a strong nation unless we are a healthy nation. And so we must recruit not only men and materials but also knowledge and science in the service of national strength.”

In contrast to Roosevelt’s soaring oratory, Spock’s noontime address on Oct. 15, 1969, was a hard-hitting censure of American involvement in Vietnam framed largely around the proposition “that the illegality and immorality of the war justifies dissent.” Spock added with a flourish: “The only way that we can save ourselves; the only way that we can get along in the world, in the long-run, is by being able to see the realities. And when we falsify the realities by calling ourselves the ‘good guys’ when actually we are the aggressor, we are starting a perilous course which could easily result in annihilation of ourselves and, in fact, the whole world.”

Although Spock’s lecture was the focal point of the anti-war activities at NIH, it was by no means the only such protest. The Vietnam Moratorium Committee communicated its message through a periodic newsletter (Rainbow Signs, circulation 6,000) that featured on its masthead a quote from the Code of Ethics for Government Service: “Loyalty to the highest moral principles and to country above persons, party, or government department.”

There were risks associated with moratorium committee membership. Citing the power of the government to intimidate protesters, one of the group’s founding members, David Reiss, a former clinical associate, later recalled: “I don’t think it’s fair to underestimate how frightening and how daunting and maybe just how discouraging it is to mount such an effort.”

Those fears were anchored in the belief that careers were put at risk by speaking out against the war. The ACLU lawyer who worked with the moratorium committee, Zona Hostetler, remembered: “There were stories of employees actually being demoted because of their anti-war activities. Even in authorized meetings of government employees on their lunch hour, security people would come in and take pictures of the people who were attending and ask for membership lists of the organization.”

Perhaps even more ominously, the FBI under Nixon conducted investigations, both public and secret, of anti-war protesters. For example, one moratorium committee member, Irene Elkins, recalled FBI agents interviewing her current and prior supervisors when she served as the co-coordinator.

Political activism was not the primary or even secondary focus for most clinical associates at the NIH during the Vietnam era. They came to Bethesda for very specific reasons: to expand their knowledge of science and to learn enough about research methods to develop a career as an independent investigator. Without question, the war and the doctor draft played a critical role in physicians’ decisions to choose the NIH over the military, but the associates tended to view their choice more as a step in professional development than as a political statement.

For most associates, the “Yellow Beret” epithet was tinged with a bit of sarcasm. Fauci, a member of the clinical associate class that entered in 1968, observed, “It was somewhat of a derogatory term. Yes, it was part joke, but very much derogatory.”

Associates did not refer to themselves as Yellow Berets. Later, as emotions faded and many of the former associates went on to distinguished careers, the term became more a badge of honor. A flavor of that sensibility is reflected in a poem by Dr. Bernard Babior, who became an associate in 1965 and later headed the Division of Biochemistry at the Scripps Research Institute. While at NIH, Babior trained under noted biochemist Earl Stadtman and many years later offered the following poem in Stadtman’s honor:

Whereas my draft board said to me “1A,”

I from ascetic Boston made my way

Bethesdawards, to Stadtman’s realm secure

To soldier for a while in the Yellow Beret.

There midst foul smells,

with compounds split by light,

With black shades pulled,

the lab as black as night . . .

I strove for data pleasing in Earl’s sight.

After training at NIH, Yellow Berets typically returned to academic institutions where they had a profound impact. A 1998 survey indicated that almost a quarter of Harvard Medical School professors of medicine were alumni of the NIH associate program. Similarly, more than 1 in 5 professors of medicine at Johns Hopkins had a tour of duty as an NIH associate.

A dozen years later, another review indicated that associate program alumni were twice as likely to become a medical school department chair and three times as likely to become a medical school dean.

In addition, 64 graduates of the program had been elected to the prestigious National Academy of Sciences, representing almost one-fifth of the members in the biomedical fields, and 125 were elected to the U.S. Institute of Medicine. Ten alumni were awarded the National Medal of Science, and nine won Nobel Prizes.

It is hard to imagine that the tidal wave of talent that washed through the NIH during the Vietnam War will ever occur again. Mike Brown, Harold Varmus, Bob Lefkowitz, and Joe Goldstein rode that wave into Bethesda and on to Nobel Prize-winning careers. V

Excerpted from Medal Winners: How the Vietnam War Launched Nobel Careers, by Raymond S. Greenberg, © 2020, published with permission from the University of Texas Press. Raymond S. Greenberg is a cancer researcher and the former executive vice chancellor for health affairs at the University of Texas System.

This excerpt was featured in the August 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here: