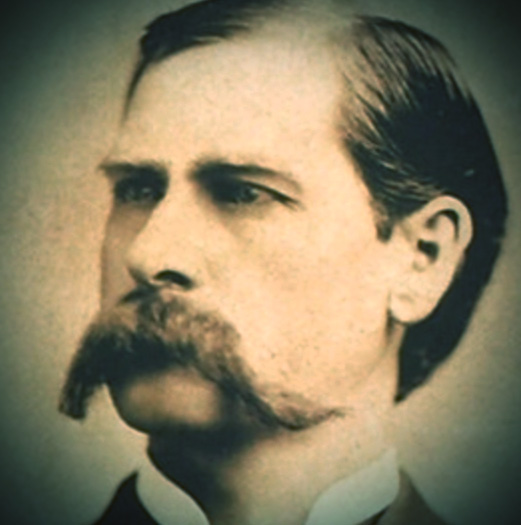

After the gunfire ceased, before the wild stories bordered mythology, the man that would become the legend of Wyatt Earp needed to simply make a living. It was in this normal path that Wyatt Earp landed in the Coeur d’Alene country in Idaho Territory during the rush of 1884. At that time, such names as Eagle City, Raven and Murrayville lingered on the lips of investors and miners alike, hungry for the next big strike that would bring gaudy wealth to a generation of hopefuls. This was the American Dream of the latter half of the 19th century—that veins of gold or silver or tin or potash would appear in the ground to make that dirt-dog job of mining worthwhile and allow the men who once swung pickaxes to wrap their calloused fingers around wads of cash.

Earp eschewed the axes for the hammer—or at least getting the miners hammered. Earp and his brother Jim arrived in Eagle City with distinct plans to make money. They purchased a circus tent 45 feet high and 50 feet in diameter and started a dance hall. They would soon open the White Elephant Saloon, which an advertisement in the Coeur d’Alene Weekly called “The Largest and Finest Saloon in the Coeur d’Alenes.” The once gunslinging Earps had again become businessmen, serving one of the most basic public needs, providing barrels of whiskey to lubricate the thirsty miners and swirling women to keep them entertained.

In 1882 A.J. Pritchard discovered gold in the Coeur d’Alene region, high on Idaho’s panhandle. It was a remote, tough area, with snowstorms covering the district during the winters and rough mountain passes preventing easy entry. It would be hard work just to get there, and harder work to extract those minerals from the ground. Yet, at the snowmelt of 1884, little communities there began to thrive, with miners and their suppliers arriving from around the West.

The Earp brothers settled into their role, running the saloon and taking on a few extra duties. Wyatt Earp was appointed deputy sheriff of Kootenai County, something of a complex situation since the mining district was in an area claimed by both Kootenai and Shoshone counties, and the legislature had not yet determined the boundaries. Even in remote Idaho Territory, this job took on some risk. On March 29, 1884, two groups of miners disputed property ownership, and chose law of the gun over law of the courts.

The Spokane Falls Review reported that about 50 shots were quickly exchanged by the warring factions when Wyatt and Jim Earp stepped between the two parties. Taking on the role of peacemakers, “with characteristic coolness they stood where the bullets from both parties flew about them, joked with the participants upon their poor marksmanship and although they pronounced the affair a fine picture, used their best endeavors to stop the shooting.” Shoshone County Deputy Sheriff W.F. Hunt arrived a few minutes later and helped quiet the battle, encouraging the leaders of both factions to smoke together and reach an understanding. The sole casualty was an onlooker shot through the fleshy part of the leg.

As a deputy sheriff and saloonkeeper, Earp emerged as something of a community leader in the rough mining camp, though piecing together the puzzles of this outpost can be difficult. Even now, nearly a century-and-a-quarter later, we are still finding little surprises about Earp’s activities in different sojourns. Denver-based researcher Tom Gaumer located a most interesting item on Earp while combing the Helena Independent newspaper files: Wyatt Earp—legendary gunman, part-time pimp and most often saloonman—became a road builder during his stay in the wilds of Idaho.

The remote region was served by the long Thompson Falls Trail, which took some time to ship in goods from the railroad stop, over the hills in Montana Territory. However, in early May 1884, Earp decided the community needed a quicker route. In an interview with the Independent, he said: “We, speaking for Earp Bros and Enright, are now working twenty men on the Trout Creek Trail to improve its condition, and expect to have the work done in ten days; we have already completed the trail twelve miles from Trout Creek and ten miles from Eagle; the trail will be the shortest into camp—only twenty eight miles in length. We propose to put fifty saddle horses on the same. The saddle train will make the trip in one day; the pack train in two days; our relay will be at the summit.”

The Trout Creek Trail would enable pack trains to bring in those necessary supplies to the hungry and thirsty miners at a much quicker pace, cutting days off the travel time from the longer trails. This way, he could assure that the miners would not be long separated from their most desired barrels of quality whiskey.

Spokane researcher Woodson Campbell located an article in the Helena Independent a week later indicating the trail had been completed. A shipment of 200 ounces of gold was taken from the diggings to Helena. “Jack Enright and Wyatt Earp escorted him (the carrier) over the trail to the railroad at Trout Creek,” the report said. Beyond that, no further mention has been found to clarify Earp’s role as a road builder.

During the summer of 2006, researcher Tom Gaumer made the trip to the Idaho Panhandle to try to retrace Wyatt Earp’s road. No markings were left to show the way, no signs. Eagle is gone now, with few remnants to mark the site of the once-booming mining district. Modern houses have spread across the area.

Gaumer located the rail stop that was once called Trout Creek in Montana and followed it part way up the mountain. He then drove to the former town of Eagle City. From Eagle, he found the markings of a winding old trail. He walked through the old forest, past stands of ancient cedar, tracing what appears to have once been a road.

“It was wide enough for horses and a pack train, but I don’t think a wagon could have made it through,” Gaumer said. “I have to admit, I had a little rush following this trail, knowing that I may have been the first person in a century to walk the road Wyatt Earp built, who knew he actually did it.”

Was this Wyatt Earp’s road? Unfortunately, no documentation remains to provide conclusive proof. The tracks of the bootheels are long gone, the mules only a distant memory. However, the distinct probability exists that Gaumer located the road built by Wyatt Earp, gunman turned community leader.

The mining boom fizzled fairly quickly in ’84. Woodson Campbell located a May 1884 article from the New York Sun describing the situation: “Gamblers, thieves, adventurers and hard men generally from all the mining camps and frontier settlements in the country congregated here, expecting to reap a rich harvest, in such that they had overdone business. They pitched their tents, opened up their banks, saloons and deadfalls, but they soon discovered that the great majority of the stampeders were without money to spare….The sports concluded that the longer they stayed here, the poorer they would be.”

The article also said, “Nearly all the celebrated desperadoes of the far West are now or have been here….The man-killer from Deadwood, Tombstone or the Comstock is pointed out very much as a citizen further east singles out the buildings or public institutions in a town of his residence in which he takes a local pride.”

No records indicate how long Earp remained in Idaho Territory. He has been identified in Raton, New Mexico Territory, in December 1884, so he apparently left before the snows blanketed the Coeur d’Alenes, forced to leave behind his investments and the road he believed would long supply the town. There would be other adventures for Wyatt Earp, more saloons, mines and even law-officering. He had many more roads to follow, but, as far as we know, no others to build.

For further reading, try Casey Tefertiller’s Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend and Richard G. Magnusson’s Coeur D’Alene Diary. The research of Tom Gaumer and Woodson Campbell made this article possible, and Tefertiller thanks them both.

Originally published in the August 2007 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.