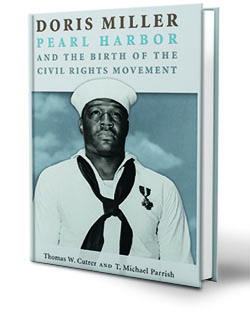

By Thomas W. Cutrer and T. Michael Parrish. 140pp. Texas A&M University Press, 2017. $24.95.

THE AVERAGE MILITARY ENTHUSIAST or student of African American history knows little about the life and struggles of the first black national hero of World War II, Doris “Dorie” Miller. The popular depiction of Miller is that of a cook aboard a battleship anchored at Pearl Harbor who leaps into action to save his mortally wounded captain during the Japanese attack. Miller then mans a .50-caliber machine gun and, although he has had no formal training, shoots down enemy aircraft. For his bravery, he is awarded the Navy Cross and receives national recognition. At that moment in American history, Dorie Miller represents the inefficiency and irrationality of racial segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces.

For most individuals, this is where Miller’s story ends, but for authors Cutrer and Parrish, this is where it begins. The authors successfully highlight just how much Miller reflects the average African American serviceman in World War II. He was an improbable hero from a rural community in Texas, whose parents were farmers and grandparents were former slaves, much like my grandfather, and many others’. Miller joins the navy at 19 to help support his family and escape the poverty, racism, and disenfranchisement typical of the African American experience. His race and lack of education relegate him to the position of a messman, charged with making beds and shining shoes for white sailors and officers.

After Pearl Harbor, a war bond tour thrusts Miller into the national scene, where his newfound celebrity becomes a burden and a source of anxiety for him and he grows increasingly depressed about his chances to live a prosperous life postwar. After receiving the Navy Cross, he tells his brother, “my life is a holy hell. The white folks never did like me because I’m colored. Now the colored guys aboard ship do not like me because they say I think I’m somebody special.” Miller convinces himself that his next active duty assignment will be a “suicide mission.” And, sure enough, when he returns to duty, a Japanese submarine sinks his ship. Two years to the day of his heroism, on December 7, 1943, the Navy Department notifies his parents that he is missing in action and presumed dead.

While the book is thoroughly researched and well written, the authors fall short in their desire to demonstrate that Miller’s entrance on the national scene reflects the “birth of the civil rights movement.” In fact, the civil rights movement and its connection to African American military bravery and service predate the American Revolution.

The authors also share the romantic notion that Miller and others like him had a moral or ethical impact on Washington and the U.S. Armed Forces that led to “greater awareness and sensitivity to the talents and loyalties of black men and women.” But changes in equal opportunity for blacks in the service were motivated by the need for military efficiency and to serve the political interest of national leaders. The fact remains that despite countless examples of African American sacrifice and heroism for the first 300 years of our nation’s history, blacks were denied civil liberties and experienced racial violence without judicial recourse until relatively recently. —Marcus S. Cox is the associate dean of graduate programs and professor of history at Xavier University of Louisiana.