Early in the war we learned that my father’s cousin Harold was a Japanese POW and had survived the Bataan Death March. We had an opportunity to send a package to Harold via the Swedish ship Gripsholm, docked in New York. Having heard that the POWs would soon go to northern Japan, we included two suits of long underwear.

After the war Harold shared his experiences with us, including the delivery of the Gripsholm packages. The guards picked through the contents of all packages and doled out selected items. When Harold’s package was opened, the guards displayed the long underwear. There was much laughter since the POWs were still being held in the Pacific islands. Distracted by the humor of the underwear, Harold received the entire package.

Harold did indeed ship out to labor in the mines in northern Japan, where it was cold and the Japanese threw cold water on the POWs as they marched to their work site. The warm underwear helped him get through his time as a prisoner.

I retain two things from Harold’s visit: being about to count in Japanese, and a “butterfly” knife made by one of the POWs from scraps of metal and bone. It is a sturdy knife, 5 1/4 inches long when folded, 9 5/8 inches fully open with a 5-inch blade.

Maxwell L. McCormack Jr.

Thorndike, Maine

—

On May 6, 1945, my uncle, Frank E. Drudge, was a squad leader with the 85th Division of the Fifth Army in northern Italy. The Allies had the Germans penned up in the town of Udine in northern Italy. The next day, May 7, 1945, was V-E Day, and it also happened to be Frank ‘s birthday. The Allies took over a walled compound in town as headquarters, and the soldiers were told they could not leave the compound. However, the German soldiers were free to roam the town, including the pubs.

This was too much for my uncle Frank, since not only was the war over, it was also his birthday. Consequently, he sneaked out of the compound and celebrated the end of the war in a pub with his many new German and Italian friends. The next morning, he woke up safe and sound in his bed inside the compound.

Shortly, he was called in to see his captain, who asked him if he knew that the Americans were confined to the compound. When Frank answered “Yes, sir,” the captain asked if he left the previous night. “No sir,” Frank replied. “Then what in the hell were those two Germans doing pounding on the gate last night when they brought you home at 2:30 in the morning?” yelled the captain.

One day before they were mortal enemies, but on this day of armistice, these two good Germans just wanted to make sure their new friend got “home” safely.

Steve Sittler

South Bend, Indiana

—

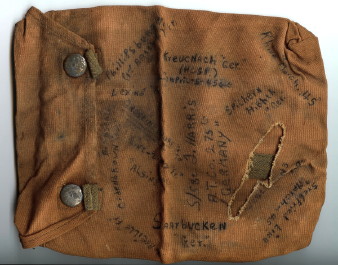

After the death of my father, Thomas Quincy Harris, in 1998, his items were given to me. One item is a canvas canteen holder, recently found in my father’s papers. It seems to be his journal for Europe. Some parts of the canvas are extremely difficult to read, but for the most part, it details where he was in Europe. I do not believe this list is comprehensive since he joined in December 1940 and left the service in December 1945.

Some of the places listed are: West Plains, Mo.; Siegfried Line, March ‘45; Saarbucken, Germany; Marseille, Fr.; Cadenbrown, Alsing, Zinz-Zinz, Phillipsburge (1st Battle), Fr.; Kreucnach, Germany (Hospital) April 5 ‘45; Spichern Highth, Germany; Rhine, March ‘45; and – two extremely difficult to read toward the top center of the canvas – Bannstal (?); Groslineadorf.

I wish I had more information to impart; but my father was deeply affected by the war. Most usually when he spoke of the war, it was to impart something humorous; such as, he was a sleepwalker during this time and his buddies were extremely worried he would sleepwalk right out on to the line. Normally any story told of the war was one where we all would laugh; very few were ever stories to cause anguish, fear, or pain.

Shauntel R. Harris-Highley

Vinita, Oklahoma

[continued on next page]