How the Allied policy of “steel not flesh” saved lives—and yielded victory.

For many, the human experience of fighting World War II is best represented by Tom Hanks unscrewing the lid of his water flask with shaking hands as his landing craft approaches Omaha Beach and then, as the ramp goes down, jumping into one of the most vividly realistic action sequences ever seen on screen. “That bit when Hanks’s character kinda goes into a bubble and noise is blocked out,” U.S. Army Ranger veteran Warren “Bing” Evans told me, “that was what it was like for me.” Bing made four landings in the war, so he knew what he was talking about.

The film Saving Private Ryan and television series such as Band of Brothers have had an enormous impact on our collective perception of war. Yet for all the brilliance of these productions, they give a distorted picture of history—especially that of the Allies’ war (and not because Rommel’s beach defenses were reversed or the beach shown was too narrow to have been Omaha).

It’s not only filmmakers who are guilty of distortion: documentary makers and historians are as well. Our view of the Allied experience of the war tends to be of landing craft, tanks, bomber crews—those at the front end of war. And yet one of the most brilliant and underappreciated Allied strategies of World War II is that those frontline fighters represented the few, not the many. By D-Day, only about 14 percent of the U.S. First Army, for example, was infantry, and just 8 percent were in tanks. Almost 45 percent were support troops—ordnance and maintenance, supply and medical staff.

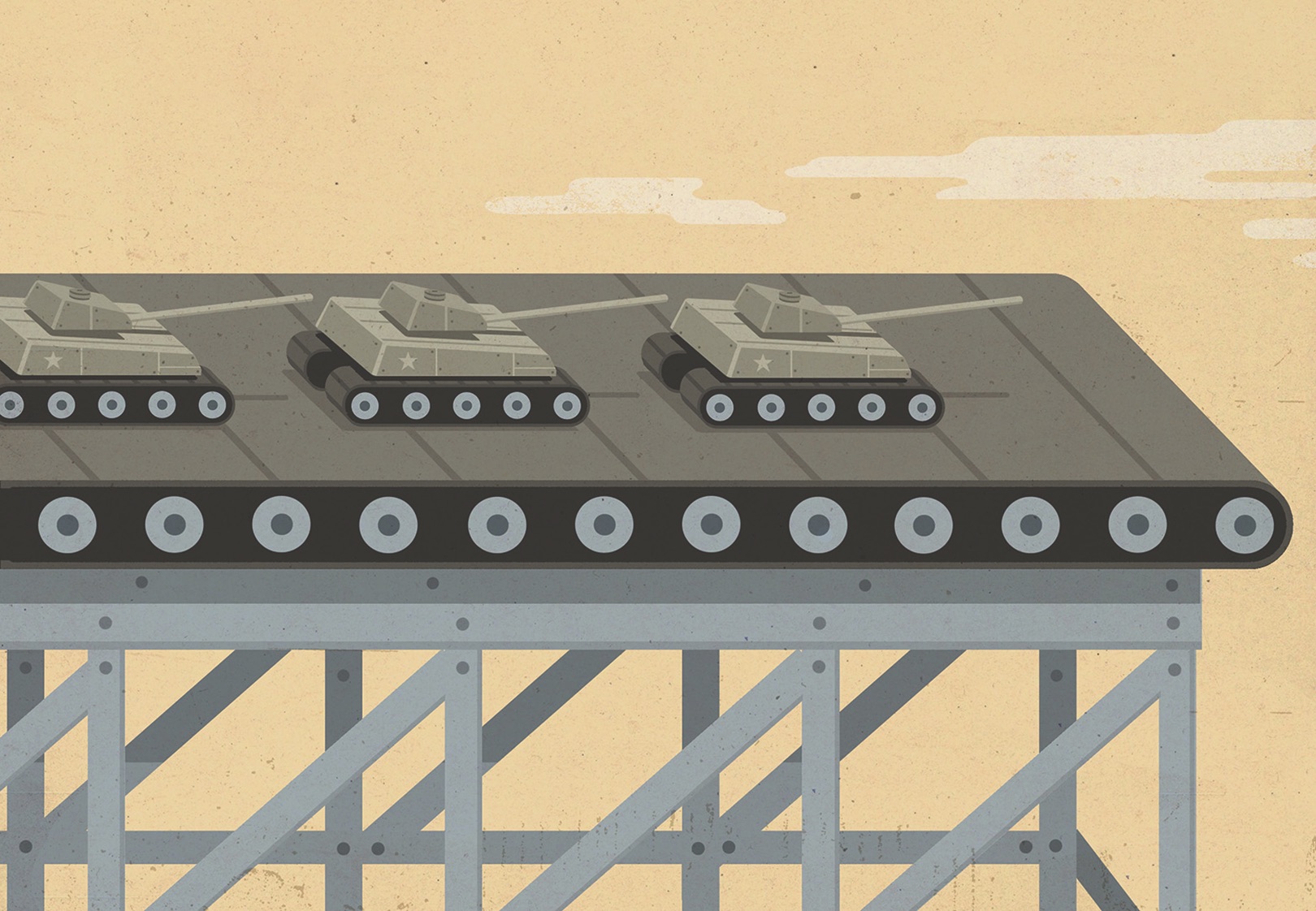

This was a deliberate strategy. Before the war, Britain had decided it was going to use “steel not flesh” as much as possible. The slaughter of a generation in 1914-18 could not be permitted to happen again, and Britain—with its vast global reach—had the wealth and the access to the world’s resources to allow technology, mechanization, and industry to limit the number of young men putting their lives at risk. The U.S., once it began furiously rearming in 1940, followed suit, and was better placed even than Britain to do so.

While Germany, Japan, and the Soviet Union continued to create ever-larger numbers of divisions—most of them infantry—Britain and the U.S. decided to maintain as few as possible. Instead, those in the infantry, or in tanks, would be the tip of the spear. Following behind would be immense firepower and extraordinary materiel support. The United States didn’t become the “arsenal of democracy” just because it had the industrial capacity; it did so because its war leaders cared about the lives of its young men in a way Hitler, Stalin, and Hirohito did not.

What the Western Allies created is what I’ve come to call “Big War,” in which those nations were fighting on land, in the air, and at sea, with the army, air force, and navy all inextricably linked. Armies on the ground would seize territory—but did so knowing they had greater artillery, more tanks, and more high-quality medical support than their enemies. If an aircraft was shot up, a new one would be available the next day. A crew might have their tank knocked out, but it would be repaired or replaced in quick order. The long tail of supply was astonishing. On July 18, 1944, for example, the British lost 493 tanks to battle damage—yet within 24 hours, 218 of them were back in action. By contrast, when a German tank was knocked out, it remained that way.

For those on the front line, World War II was appallingly dangerous, but the “steel not flesh” policy was a far more efficient way to fight than the Axis and Soviet approach and ensured that far fewer men had to put themselves in the firing line. That’s why by the end of the war, both the United States and Britain had substantially fewer casualties than their enemies, despite fighting a truly global conflict. A war movie about factories and logistics might not grip audiences in quite the same way as Tom Hanks leaping from a landing craft, but it was the incredible Allied supply chains as much as the raw courage of those at the front that brought victory in 1945. ✯

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.