‘The blast shattered windows in lower Manhattan and along the Jersey waterfront and awakened people as far away as Maryland and Philadelphia’

From the air the soot-covered Lehigh Valley Railroad terminus at Jersey City, N.J., looked like a black cat with an arched back, calling to mind its nickname “Black Tom.” The depot rested atop Black Tom Island, which jutted into New York Harbor. In 1916 some three-quarters of the ammunition manufactured in the United States and destined for the Allied armies on the Western Front shipped from there. Still, few Americans gave it much thought, despite its prime location near the Statue of Liberty and lower Manhattan.

To German agents active in the New York City area, however, Black Tom became an obsession. After all, the depot served as the transit point for arms going from America to the very armies killing German soldiers. To the German government it made a mockery of President Woodrow Wilson’s stated policy of American neutrality. The round-the-clock operations at Black Tom proved beyond doubt to the Germans that the Americans were hardly neutral. They were instead providing Germany’s enemies with the means to continue the war.

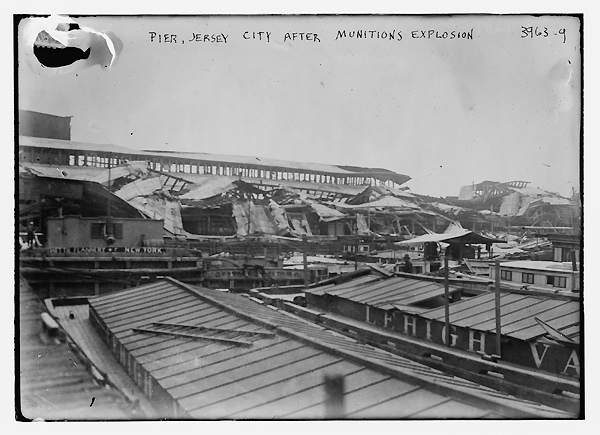

In the dark, early morning hours of July 30, 1916, even as German soldiers vied against those of Britain and France in the murderous Battles of Verdun and the Somme, a massive explosion ripped through Black Tom. More than 1 million pounds of ammunition and TNT on the docks detonated, causing a series of shocks equivalent to a 5.5-magnitude earthquake on the Richter scale. The blast shattered windows in lower Manhattan and along the Jersey waterfront and awakened people as far away as Maryland and Philadelphia. It killed at least five people, including a 10-week-old infant thrown from his crib more than a mile from the blast. Security guards rushed to evacuate Ellis Island, fearing that cinders from the explosions might set the immigrant dormitories on fire. Officials later checked the structural integrity of the nearby Brooklyn Bridge and closed the Statue of Liberty’s shrapnel-scarred torch arm to tourists. Property damage was later estimated to exceed $20 million (more than $400 million in 2013 dollars).

Given the risk of further explosions, the authorities’ first concern was to minimize further loss—not to investigate the cause of what was then the costliest manmade disaster in American history. Destruction near the blast epicenter was so complete that investigators had trouble collecting forensic evidence. Six piers, 13 warehouses and dozens of railcars had simply vanished; in their place gaped a 300-by-150-foot crater filled with contaminated water and debris.

Within days the investigation centered on two night watchmen who had set smudge pot fires to deter the port’s invasive and annoying mosquitoes. But police soon ruled out the smudge pots as a cause, concluding they were too far from the munitions to have triggered the blast. It became apparent, moreover, that the catastrophe was no accident. It had begun at the far end of the terminal, the perfect spot to both escape detection and set off a chain reaction. More and more the Black Tom explosion was looking like a deliberate act of terror.

One man, New York City Police Department inspector Thomas J. Tunney, had an idea who might have been behind the brazen and dastardly sabotage at Black Tom. Tunney was an Irish-American veteran of the NYPD who had a deep knowledge of bombs from his time tracking anarchist groups around the turn of the century. In 1916 he was head of the NYPD bomb squad, which by then had turned its focus on foreign agents. Along with two other lawmen, A. Bruce Bielaski and William Offley, Tunney had formed a task force to investigate allegations of a German spy ring running out of New York City. Notably, Tunney named his task force the Bomb and Neutrality Squad.

Although officials hadn’t turned up much evidence of an organized effort, indications suggested German agents were active across the United States and Canada. In 1914 U.S. federal agents had uncovered a German plot to dynamite Ontario’s Welland Canal, with the twin goals of disrupting commerce and convincing the Canadian government to stop its support of Great Britain. In February 1915 a German agent set off a dynamite-packed suitcase on a railroad bridge between Canada and the United States at Vanceboro, Maine, but caused only minor damage. Authorities foiled other plans for sabotage in Seattle, San Francisco and Hoboken, as well as a plot to buy American passports from dockworkers and use them to bring German agents into the country; the latter prompted federal officials to introduce photographs on passports.

Although officials hadn’t turned up much evidence of an organized effort, indications suggested German agents were active across the United States and Canada. In 1914 U.S. federal agents had uncovered a German plot to dynamite Ontario’s Welland Canal, with the twin goals of disrupting commerce and convincing the Canadian government to stop its support of Great Britain. In February 1915 a German agent set off a dynamite-packed suitcase on a railroad bridge between Canada and the United States at Vanceboro, Maine, but caused only minor damage. Authorities foiled other plans for sabotage in Seattle, San Francisco and Hoboken, as well as a plot to buy American passports from dockworkers and use them to bring German agents into the country; the latter prompted federal officials to introduce photographs on passports.

The German ambassador, the likeable and pro-American Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff, denied the existence of any plot, claiming these actions were those of individuals not connected to the German embassy. The Wilson administration, eager to preserve American neutrality, took him at his word, even though Tunney and other law-enforcement officials were uncovering evidence to the contrary.

The Vanceboro plot yielded the first big break. The man who placed the dynamite on the bridge was a dimwitted German agent named Werner Horn. He set the charge on the Canadian side of the span, then ran back to the American side to evade arrest as a spy in a belligerent nation. American officials had little trouble finding Horn, as he had changed into his German army uniform in order to claim to the neutral Americans he was a soldier not a spy. The investigation soon revealed that Horn’s paymaster was Franz von Papen, a former military attendant to Kaiser Wilhelm II and military attaché in Washington, D.C., who had returned to the United States in 1914.

Papen had diplomatic protection and political savvy. Investigating him would not be easy, but Tunney and his lieutenants, with help from federal officials, persevered. They soon met with a federal prosecutor involved in the Welland Canal investigation who told them that while he had been unable to prove the connection, he had evidence Papen had been involved in that plot, as the one to hire Irish-Americans to sabotage American shipping.

The mounting evidence was too much even for the Wilson administration and its desire to maintain American neutrality. At year’s end 1915 the government ordered Papen to leave the United States. He did so, and a confiscated briefcase full of his papers (stolen, he claimed, by British agents) showed the Americans had been right to suspect him. Included were documents revealing a nationwide plot, from New York to San Francisco, to blow up bridges and tunnels. Papen had also planned to recruit agents and conduct a sabotage campaign, including the use of Americans and Canadians of Indian descent to target ships leaving from Pacific Coast ports. The documents also led investigators to a New Jersey–based group that had been manufacturing “rudder bombs” for saboteurs to attach to the sterns of outgoing ships. The rotation of the propellers mixed certain chemicals and thus ignited the bombs, which disabled or sank the ships. As many as 30 vessels might have been damaged or destroyed by the plot before it was uncovered. Coming in the wake of public anger over the May 1915 sinking of the British liner Lusitania by the German submarine U-20, these charges ratcheted up Americans’ fear of German activity within their own borders.

The British, meanwhile, had uncovered another arm of the German network. From intercepts obtained by the famed Room 40 decryption operation, they knew Papen had been complaining about one of his subordinates, chemist and naval intelligence officer Franz von Rintelen. They also knew Rintelen planned a return to Germany using a fake Swiss passport bearing the name Emil V. Gasche. When his ship docked in Falmouth en route to neutral Holland, the British arrested Rintelen and broke his initial insistence he was a Swiss businessman. According to his interrogator, they simply had a policeman burst into the interrogation room and shout, “Achtung!” whereupon Rintelen leapt to his feet and clicked his heels. The German spent 21 months in a British jail before being sent to an Atlanta prison for sabotage.

American agents had also been following two other Germans: former naval attaché Karl Boy-Ed, the son of a Turkish sailor and a well-known German novelist, and Wolf von Igel, Papen’s chief assistant and successor. Boy-Ed was a flashy and suave epicure well known to many in the New York elite. He was a frequent guest at the city’s Army and Navy Club, where he dazzled audiences with his knowledge of naval warfare. Sophisticated and well dressed, he mixed easily in New York social circles and was hoping to meet and marry an American heiress.

Boy-Ed had also been running a spy ring out of a welcome house and part-time brothel for German sailors on Broadway near Battery Park. American investigators had already tied him to both the passport-fraud scheme and a plan to buy property on the Atlantic seaboard where the Germans could install artillery batteries in preparation for a potential German amphibious landing. Boy-Ed, compromised by the evidence in Papen’s papers, also left the United States.

Papen and Boy-Ed left Igel in charge of the financial network that paid for these operations. He ran it out of Papen’s former office on the 25th floor of a building at 60 Wall Street, a far more respectable address than the Bowling Green house Boy-Ed used to meet with the spies he recruited. There Igel, who had been deeply involved with the rudder bomb plot, continued to run a ring of German agents. As investigators closed in, he arranged to move his papers to the German embassy in Washington and thus secure them under the umbrella of diplomatic immunity.

On April 19, 1916, Igel began packing more than 70 pounds of documents into cases for the trip to Washington. American investigators were on to him, however, and burst into his office with guns drawn. Igel leapt for the safe, trying to close it and claim diplomatic privilege, but the federal agents stopped him. As Igel shouted that the Americans were committing an act of war, the feds seized the documents. The papers proved German complicity in the Welland Canal plot, as well as in a scheme to buy arms in the United States from Irish-Americans and then send the weapons to India to fuel an anti-British uprising.

Igel’s arrest made front-page news in New York, as did the German embassy’s demand the Americans return the papers without examining or copying them. The Wilson administration did not comply with that demand, but Wilson remained anxious to play down the incident in hopes of preserving American neutrality. Although tensions mounted, Secretary of State Robert Lansing did not challenge Bernstorff’s claim the arms were in fact headed to German forces in East Africa. Bernstorff also dissociated himself and the German embassy from any illegal activities.

Wilson may have been mollified, but his archnemesis (and former NYPD commissioner) Theodore Roosevelt was not. Roosevelt had recently given a speech in Brooklyn accusing the Germans of “a campaign of bomb and torch” against American industry. The pugnacious former president laid the blame for all acts of sabotage at the feet of the German government, noting that Boy-Ed went home to a hero’s welcome and a personal decoration from Kaiser Wilhelm II. Roosevelt also noted the close relationship among Boy-Ed, Rintelen and the anti-American Mexican dictator Victoriano Huerta. In the heated political environment of 1916, which produced one of the closest presidential elections in American history, the issue of German sabotage contributed to the wider debate about the wisdom of American neutrality.

As his campaign slogan “He Kept Us out of War” indicated, Wilson hoped to maintain that neutrality. Even after the Black Tom explosion Wilson tried to avoid making the 1916 election a referendum on the war. Fortunately for him, so did his opponent, Supreme Court Justice Charles Evans Hughes. Hughes, while anxious to attack Wilson’s record on domestic affairs, had to be careful to dissociate himself from the pro-intervention agenda of Roosevelt and his supporters. Wilson’s slogan was thus less a boast than a warning about what might happen if Hughes, with Roosevelt supposedly whispering in his ears, won.

The following February, with Wilson re-elected by the slimmest of margins, New York Sun reporter John Price Jones detailed the German plots in a book that featured an introduction by Roger Wood, former assistant U.S. attorney for New York, and a preface by Roosevelt. The former president praised the book for exposing what he called a two-and-a-half-year secret war waged by Germany against the American people. Jones himself alleged the German government had bribed American newspapers to write positive stories about Germany and, in at least one instance, bought a newspaper through a shadow company to use as a propaganda vehicle.

Meanwhile, the Black Tom investigation continued. An elderly landlady in Hoboken reported to police that one of her boarders, a nephew named Michael Kristoff, had behaved strangely on the morning of the explosion, pacing and muttering to himself, “What [did] I do?” In late August police arrested him and soon broke his alibi. Kristoff then wove a wild tale about nationwide networks of German agents paid for and operated out of New York City. Without firm evidence, however, authorities had no choice but to release their suspect.

Convinced Kristoff had something to do with the Black Tom blast, Lehigh Valley Railroad officials hired a detective to shadow him. Alexander Kassman, himself a recently arrived immigrant, attached himself to Kristoff for several months, posing as an Austrian anarchist in order to dig more deeply into the co-conspirators he had mentioned. Kristoff reportedly told Kassman that rich friends had provided the funding for the Black Tom operation. One of the alleged backers, David Grossman, lived in Bayonne. Kassman arranged to meet Grossman and gleaned more details of the plot from him. Grossman denied knowing the money had been for sabotage. But, Grossman told Kassman, he later learned Kristoff had served as a lookout while another man placed dynamite on a small boat beneath the piers and a third put explosive charges between railroad cars loaded with ammunition. In spring 1917 Kristoff vanished.

Grossman refused to testify, but his interrogation helped police identify two other men—Lothar Witzke, a naval officer with an intelligence background, and Kurt Jahnke, a naturalized American citizen with connections to the German consulate in San Francisco. Both men used pseudonyms, moved around frequently and were suspected of involvement in the bomb plots on the West Coast. After Black Tom they went to the Southwest and spent time in Mexico, where both had contacts in the Huerta government.

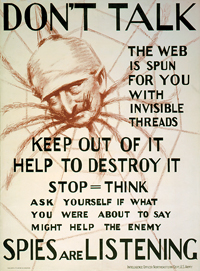

As the investigation continued to turn up leads but no arrests, Wilson’s neutrality policy collapsed. On Feb. 3, 1917, Wilson broke off diplomatic relations with Germany in response to its resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare. A few weeks later the contents of the Zimmerman Telegram, the German proposal that Mexico make war on the United States, hit American newspapers. The telegram put the issue of German sabotage in a new, more sinister light. It, coupled with continued fears of German sabotage and espionage, helps to explain, though does not excuse, the wave of anti-German sentiment that soon swept the country. Americans felt they faced a real and present danger from Germany—not overseas, but at home.

Wilson was soon out of options, and his cabinet was finally in unanimity about the need to enter the war. Roosevelt reportedly told a friend that if Wilson did not declare war, he would go to the White House and “skin him alive.” Wilson did, of course, bring the United States into a war that was no longer about the maritime rights of neutrals but the need of the government to fulfill its central role of protecting American lives and property. America’s age of isolation was over.

While several of the key players in Germany’s wartime sabotage efforts in North America went on to further notoriety, none, perhaps, had a more sinister role in history than Franz von Papen. He became chancellor of Germany in 1932 and was among the men chiefly responsible for persuading President Paul von Hindenburg to name Adolf Hitler chancellor in 1933; Papen then served briefly as Hitler’s vice chancellor.

Papen’s powerful position also allowed him to complicate continuing investigations into the Black Tom disaster, but in 1939 a German-American Mixed Claims Commission found the German government of 1916 responsible for the blast. In 1953 the commission awarded damages of $50 million, which were finally paid off in 1979. Today the Black Tom lies within Liberty State Park in Jersey City, although the only evidence of the historic explosion is a poorly worded information panel and the remnants of piers on the south end of the park. Ironically, Papen’s headquarters at 60 Wall Street is today the site of a 1989 skyscraper that houses the U.S. headquarters of Germany’s Deutsche Bank.

Michael S. Neiberg is the author of several books on the 20th century world wars, most recently Dance of the Furies: Europe and the Outbreak of World War I (2011) and The Blood of Free Men: The Liberation of Paris, 1944 (2012). For further reading Neiberg recommends Sabotage at Black Tom, by Jules Witcover; The Detonators, by Chad Millman; and New York at War, by Steven Jaffe.