Although it happened more than 35 years ago, a group of Army veterans of the Vietnam War still consider a young Air Force enlistee, a recipient of the Medal of Honor who gave his life to save theirs, the most courageous person they have ever known.

‘He was the bravest man I’ve ever seen, and I saw it all,’ said Martin L. Kroah, Jr., who served two tours in Vietnam, one as a Special Forces officer. He was talking about Airman 1st Class William H. Pitsenbarger, an Air Force pararescue and medical specialist from Piqua, Ohio, who had voluntarily left the relative safety of a helicopter to descend into a brutal jungle battle to treat and evacuate wounded soldiers in 1966. Pitsenbarger was credited with saving nine lives, after several times refusing to be evacuated himself, during a fight in which 106 of the 134 troopers were killed or badly wounded. Soon after the battle, his Air Force commanders nominated him for the Medal of Honor, but he did not receive it. An Army general recommended that the award be downgraded to the Air Force Cross, apparently because at the time there was not enough documentation of Pitsenbarger’s heroic actions.

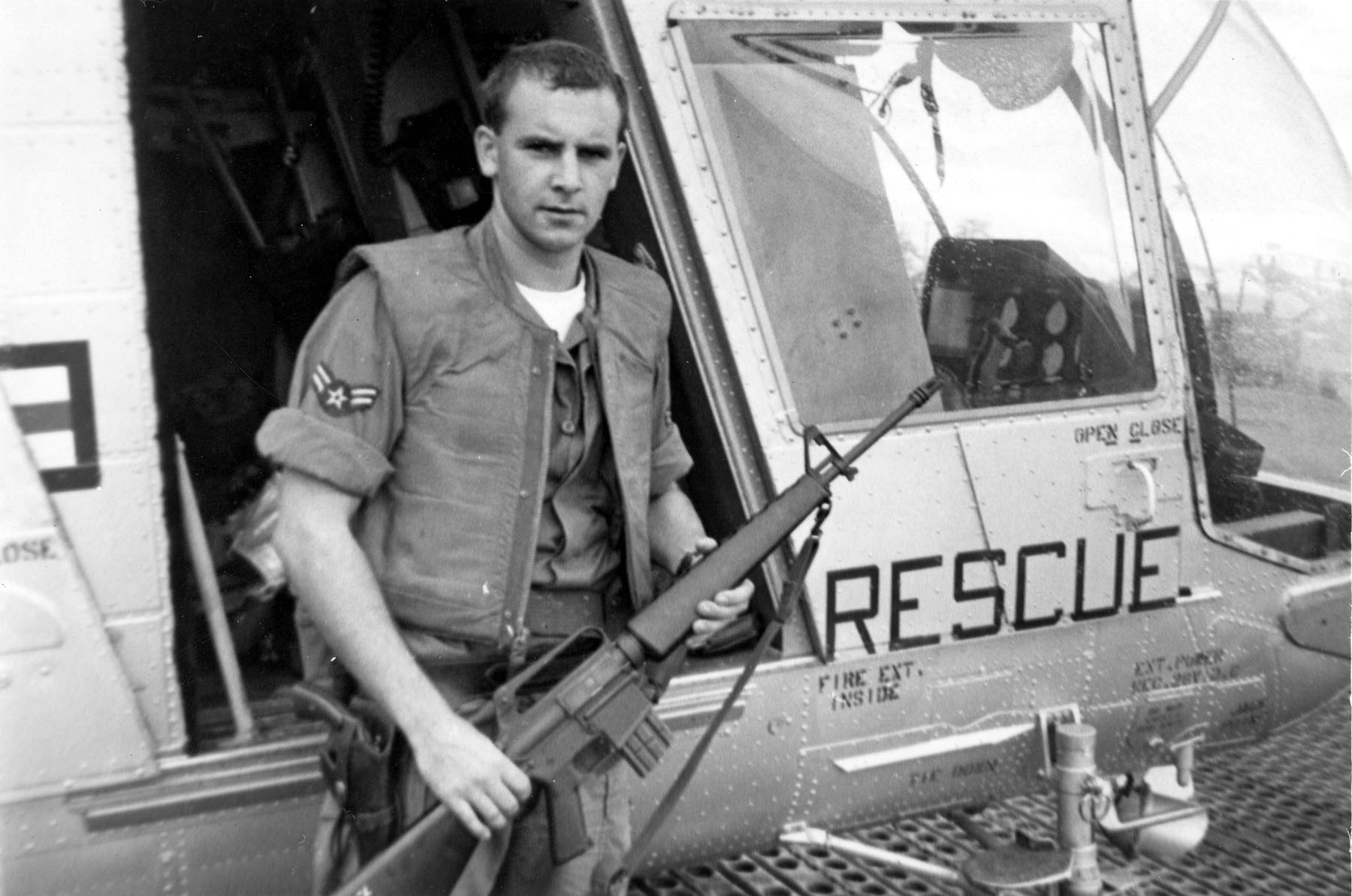

Pitsenbarger, on April 11, 1966, at his own request, descended 100 feet on a winch line from a Kaman HH-43 Huskie helicopter into a dense jungle valley and alighted in the middle of an encircled company of U.S. Army soldiers. The besieged troops were members of Company C, 2nd Battalion, 16th Infantry of the 1st Infantry Division and were under attack by VC about 35 miles east of Saigon. Regarding Pitsenbarger’s actions, Daniel Kirby of Louisville, Ky., who had been a Company C rifleman, commented: ‘I was stunned that somebody was coming down to put themselves in that situation. It’s hard to believe that someone would voluntarily come into that battle and stay with it. He had to be the bravest person I’ve ever known.’

After landing, Pitsenbarger gave first aid to the wounded, decided which men needed to be evacuated first and strapped them into a wire basket called a Stokes litter. He helped get nine GIs lifted out of the battle and flown to a nearby field hospital. He refused evacuation himself several times in order to try to save more wounded men. Then his helicopter was hit by enemy fire and nearly disabled. Before leaving the area, his pilot, Harold D. Salem of Mesa, Ariz., signaled for Pitsenbarger to ride the litter up to safety. Again, he refused and waved the chopper off.

Kroah, of Houston, said he remembered Pitsenbarger being lowered through the trees at a time when’small-arms fire would be so intense that it was deafening, and all a person could do was get as close to the ground as possible and pray.’ Before long Kroah had been wounded five times and was flat on the ground. ‘On three different occasions I glimpsed movement, and it was Pits dragging somebody behind a tree trunk or a fallen tree, trying to give them first aid,’ he recalled. ‘It just seemed like he was everywhere. Everybody else was ducking, and he was crouched and crawling and dragging people by the collar and pack straps out of danger….I’m not certain of the number of dead and wounded exactly, but I’m certain that the death count would have been much higher had it not been for the heroic efforts of Airman Pitsenbarger.’ Kroah added that the battle was so fierce that his own Army medic was frozen with fear and unable to move and that one of his fire-team leaders, a combat veteran of World War II and the Korean War, curled into a fetal position and wept.

‘For Airman Pitsenbarger to expose himself on three separate occasions to this enemy fire was certainly above and beyond the call of duty of any man,’ said Kroah. ‘It took tremendous courage to expose himself to the possibility of almost certain death in order to save the life of someone he didn’t even know….He had a total disregard for his own safety and tremendous courage.’

For the next couple of hours Pitsenbarger crawled through the thick jungle looking for wounded soldiers. He would drag them to the middle of the company’s small perimeter, putting them behind trees and logs for shelter. At one point, said Charles Epperson, of Paris, Mo., Pitsenbarger saw two wounded soldiers outside the perimeter. ‘He said, ‘We’ve got to go get those people,’ and I said, ‘No way. I’m staying behind my tree.’ It was just unbelievable fire coming at us from all sides. But he took off to get those guys, and I could see him trying to get both of them and having a hard time, so I ran out there and helped him drag them inside our lines. He was an inspiration to me,’ said Epperson.

Fred Navarro, who was seriously wounded, said Pitsenbarger saved his life by covering him with the bodies of two dead GIs, shielding him from more bullets. ‘We were getting pounded so bad that I could only lie on the ground for cover. Pitsenbarger continued cutting pant legs, shirts, pulling off boots and generally taking care of the wounded. At the same time, he amazingly proceeded to return enemy fire whenever he could,’ said Navarro, of San Antonio, Texas.

F. David Peters, of Alliance, Ohio, had been in Vietnam only two weeks at the time of the incident. He recalled that he was terrified when he was told to help Pitsenbarger during the firefight. ‘I don’t remember how many wounded were taken out when we started taking small-arms fire,’ said Peters. ‘I remember him saying something to the [helicopter] pilot like, get out of here, I’ll get the next one out. His personal choice to…get on the ground to help the wounded is undoubtedly one of the bravest things I’ve ever seen,’ said Peters.

Johnny W. Libs, a seasoned jungle fighter who was leading Company C that day, said he’d never seen a soldier who deserved the Medal of Honor more than Pitsenbarger. He recalled telling one of his machine-gunners, Phillip J. Hall, of Palmyra, Wis., that Pitsenbarger was out of his mind to leave his chopper for ‘this inferno on the ground. We knew we were in the fight of our lives and my knees were shaking, and I just couldn’t understand why anybody would put himself in this grave danger if he didn’t have to.’ Libs, of Evansville, Ind., also said that Pitsenbarger seemed to have no regard for his own safety. ‘We talk about him with reverence. I [had] never met him, but he’s just about the bravest man I have ever known. We were brave, too. We did our job. That’s what we were there for. He didn’t have to be there. He could have gotten out of there. There’s no doubt he saved lives that day.’

Hall said that Pitsenbarger’s descent into the firefight ‘was the most unselfish and courageous act I ever witnessed. I think of him often now,’ he added. ‘That thing never leaves my mind totally. He did actually give up his life for guys on the ground that he didn’t even know. And he didn’t have to be there. I know he made the conscious decision to stay there.’Salem said that Pitsenbarger had volunteered to go to the ground because the soldiers were having trouble putting a wounded man into the wire basket to be lifted out. The helicopter pilot recalled telling Pitsenbarger that he could leave the chopper only if he agreed that, when given a signal, he would return to the aircraft. ‘As we were [getting in position], I said, ‘Pits, it’s hotter than hell down there; do you still want to go down?’ He said, ‘Yes sir, I know I can really help out.’ He made a hell of a difference. We ended up getting nine more out after he got on the ground. He is the bravest person I’ve ever known,’ Salem said.

Near dusk, as the VC launched another assault, Pitsenbarger fought back with an M-16. Then, Navarro said, he saw him get hit several times as he made his way toward what Navarro thought was another wounded man. Pitsenbarger was shot four times, once between the eyes, and died on the spot. The next day one of Pitsenbarger’s best friends, Henry J. O’Beirne of Huntsville, Ala., a former Air Force pararescueman who had served with him and been his bunkmate, recovered his body. ‘He was an ordinary man who did extraordinary things,’ said O’Beirne.

The man called Pits by his friends was born and raised in Piqua, a blue-collar town of 22,000 on the Great Miami River in west-central Ohio, about 30 miles north of Dayton. Pitsenbarger was an only child. His father, Frank Pitsenbarger, said that his son had never been afraid of anything. His friends remembered him as an adventurous youngster who would climb the highest tree or scale the tallest building.

Judy Meckstroth, who worked with him at a local supermarket when he was in high school, said he loved to play poker, was a ladies’ man, won dance contests, and showed concern for other people, both young and old. Meckstroth added that he was ‘ornery and fun-loving. You didn’t dare walk into the back room because he’d hide behind boxes and jump out and scare you to death. But I never heard anything bad about him. It was nothing to have 10 or 15 girls in the store on weekends; they’d come in to buy a pack of gum just to see him. But he wasn’t big-headed about it. He was just good-looking and had a real magnetic personality.’

Bob Ford, a retired Piqua assistant fire chief who knew him most of his life, said Pitsenbarger had two other loves: baseball and playing soldier. ‘There were lots of war movies then, and we played soldier in the streets and alleys all the time. He lived a block away from [a park] and there were always pick-up baseball games,’ he said.

Veterans of Company C felt so strongly about the 21-year-old airman’s heroism that they–along with his former Air Force colleagues, his high school classmates and his hometown chamber of commerce–worked for more than three decades to see that he finally received, posthumously, the nation’s highest award for valor. On December 8, 2000, Pitsenbarger’s father was presented with his son’s Medal of Honor by then Air Force Secretary Whit Peters in a ceremony at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. Looking on were 10 of the Army veterans whose eyewitness testimonials had persuaded the Pentagon and Congress to approve the award Pitsenbarger should have received in 1966. Also present were several of his school classmates and some of his Air Force friends, all of whom had worked to get him the medal. Of the December Medal of Honor ceremony, Bob Ford said, ‘It was a very sad thing, but a happy sad.’

Pitsenbarger was the first Air Force enlisted man to earn the Medal of Honor since the U.S. Air Force was established as a separate service in 1947. In 1945, in the era of the U.S. Army Air Forces, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress crewman, Henry Erwin, was awarded the medal for saving his crew and aircraft on a bombing run over Japan. One other Air Force enlisted man received the medal for heroism in Vietnam. John Levitow, an Air Force load master in Vietnam, earned the medal in 1969, three years after Pitsenbarger was killed in the action for which he was posthumously awarded the medal 35 years later.

Levitow himself campaigned for Pitsenbarger’s medal and contended that the deceased airman should be considered the first Air Force enlisted recipient in Vietnam. Levitow died exactly one month before Frank Pitsenbarger was presented with his son’s Medal of Honor.

The Medal of Honor ceremony in Dayton was emotional for all who attended. ‘There wasn’t a dry eye in the house,’ said Cheryl Buecker, who went to Piqua Central High School with Pitsenbarger in the class of 1962. ‘I was proud the community helped accomplish this,’ she added.

It was only after the ceremony that details of his courage were made public. Toward that end, W. Parker Hayes, Jr., a historian with the Air Force Sergeants Association, had tracked down the Army veterans who had served with Pitsenbarger. Hayes said that in the 1990s an array of people had approached the association seeking help in honoring Pitsenbarger, including O’Beirne; Salem; Dale L. Potter, of Enterprise, Ore., a chopper pilot who also flew rescue operations with Pitsenbarger; Paul D. Miller, another pararescue specialist; some Piqua residents; and members of the Piqua Chamber of Commerce. All had wondered for years why the Medal of Honor had not been awarded to Pitsenbarger. Buecker and classmate Bob Ford said they had begun talking about the issue 20 years earlier at a class reunion planning meeting.

‘We’re a really tight class,’ said Buecker, noting that they held a reunion every five years and always put up a ‘memory board’ carrying obituaries of classmates, along with news clippings and letters from living classmates who could not attend the reunion. ‘At each reunion it seemed like there was something new about Bill to go on the board,’ Buecker added. In fact, more than a dozen military facilities around the world have been named for Pitsenbarger since his death. In the early 1990s, the classmates started a campaign to convince the Pentagon he deserved the medal. They talked to aides of their congressmen and wrote letters, but did not get very far until 1996. Then they, along with the chamber of commerce and some Air Force pararescuemen, joined forces with Hayes and his fellow historian, William I. Chivalette, at the Airmen’s Memorial Museum, operated by the Air Force Sergeants Association, near Washington, D.C. Hayes and Chivalette did exhaustive research on Pitsenbarger’s last mission. Hayes collected statements from the Army veterans in 1998 and 1999, and a medal nomination package was sent to the Pentagon. On October 6, 2000, Congress approved a bill that included awarding the Medal of Honor to Pitsenbarger.

The 1962 class of Piqua Central High School had also felt it was a shame that his hometown had never honored him. In 1992, Cheryl Buecker and her husband Tom, who was president of the 1962 class, persuaded David Vollette, president of the Piqua Chamber of Commerce, to join their effort. In 1993 they got the town government to change the name of Piqua’s 67-acre Eisenhower Park to the Pitsenbarger Sports Complex, with a granite monument and bronze plaque, paid for in part by donations from ’62 classmates.

‘We had a deep desire as a community to see something happen. We knew [Pitsenbarger’s] father was hurt that he didn’t get the medal,’ said Cheryl Buecker.

Tom Buecker said that in 1991 he had discussed the medal with aides of the area’s U.S. congressman, Representative John A. Boehner, but nothing much had developed from it. The Bueckers said they did not know the process or what was needed in Washington, or even if it was possible for someone to receive the Medal of Honor after so many years.

In 1996, Chivalette went to Piqua to gather material to write a monograph on Pitsenbarger. During his visit, high school classmates and chamber of commerce members mentioned their efforts for a Piqua memorial and the Medal of Honor, and the Bueckers discussed the process with him.

In writing his monograph, Chivalette be-came convinced Pitsenbarger deserved the medal. He researched the case until early 1998, when he turned it over to Hayes, since he was leaving for a new job with the Air Force Enlisted Heritage Hall in Alabama. Meanwhile, the Sergeants Association had been separately contacted in the spring of 1998 by Air Force pararescuer Paul Miller, who also sought help in trying to obtain the medal for Pitsenbarger. The Airmen’s Memorial Museum assembled a nomination package, with helicopter pilot Harold Salem signing the recommendation. Retired Maj. Gen. Allison C. Brooks of Sequim, Wash., who was in charge of Air Force rescue units in Vietnam in 1966, provided an endorsement, and Representative Boehner recommended approval of the medal and sent the package to Secretary Peters.

On April 7, 2001, Piqua held a community celebration of Pitsenbarger’s life and heroism, marked by the unveiling of a replica of an Ohio historical marker. There also was a fund-raising dinner for the William H. Pitsenbarger Scholarship Fund, established in 1992 by his father and his late mother, Irene. There is now talk of putting up a statue of Pitsenbarger in the town square. For his father, friends, classmates and the town of Piqua, the ceremonies helped bring what seemed to be a fitting end to an almost forgotten episode of the Vietnam War. ‘It brought closure for me, and I think for the whole town,’ said his father.

The article was written by Lacy Dean McCrary and originally published in the June 2002 issue of Vietnam Magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Vietnam Magazine today!