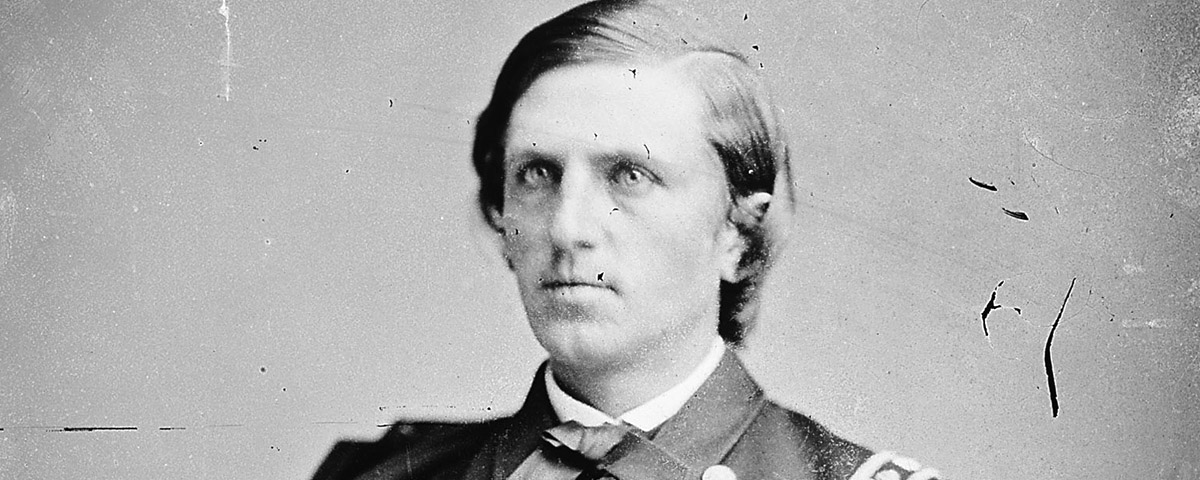

Brash, Dashing…and Effective

Youthful William Cushing bedeviled Rebels with daring raids on North Carolina’s hazardous Cape Fear River

Lieutenant William Barker Cushing of the U.S. Navy pulled off one of the most implausible featsof the Civil War on October 28, 1864, when he sank the notorious Confederate ironclad ram Albemarle with a torpedo launched from a small open boat. But the Albemarle triumph was presaged by a number of other successes for the audacious and quick-thinking Cushing. Two of those escapades occurred within four months of each other early in 1864.

In February 1864, Cushing—then 21, and the youngest lieutenant in the history of the Navy—was assigned to the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, based at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, and given command of USS Monticello. By that point North Carolina, with its many twisty rivers and hidden inlets, was one of the few places where Rebel blockade runners still enjoyed success. Their preferred port was Wilmington, 28 miles inland from the mouth of the Cape Fear, a river well-protected not only by forts and batteries, but also by shifting currents, changing depths, unmarked shoals and marshes and other navigation hazards that could ensnare even experienced pilots familiar with the area.

Soon after his arrival on February 17, Cushing, true to his reputation for independence and aggressiveness, brought his superiors a proposal to take 200 men and seize Smith’s Island, at the mouth of the river. Doing so would close one of the two entrances that blockade runners used to enter the river, and tighten their pass through the other. But Cushing’s superior, Captain Benjamin Sands, considered the plan risky and denied him permission with a curt, “Can’t take the responsibility.” As Cushing wrote later, “This, I confess, provoked me, and I told the Senior Officer that I could not only do that, but if he wanted the Confederate general off to breakfast, I would bring him.” He then began laying plans to do exactly what he had proposed.

Shortly after sundown on February 29, Cushing took 20 men in two small boats and rowed several miles up the Cape Fear, past the guns of Fort Caswell and Fort Johnston, past the town of Smithville, where Brig. Gen. Louis Hébert, the Confederate commander of the area, made his headquarters.

Having sneaked past Smithville, Cushing’s raiders turned and approached the town from the opposite direction, so anyone who might be watching would think they were coming downriver—and must therefore be friendly. After beaching the boats, Cushing took half his men into the one-street town. Even at night, its layout wasn’t difficult to discern: the general store, the stable, the larger building that was a hotel. At the end of the street, the building with narrow windows would be the fort. Hébert would be staying somewhere comfortable, in a house. But which one?

Ahead of him Cushing could see a dark building where a large fire was burning—a salt works. Two black men, no doubt slaves, were sitting by the fire. “Where’s the general?” Cushing asked. One of the men led him and two of his officers, Ensign J.E. Jones and Master’s Mate W.L. Howorth, to a house with a large veranda.

Cushing crept onto the porch and quietly opened the door. Easing his way along as his eyes adjusted to the dark, he determined that he was standing in a dining room, and then a hallway. He had begun climbing the stairs when he heard a crash from below, with Howorth calling for him. Cushing hurried back to the dining room, where a large man in a nightcap confronted him, a chair raised above his head. The lieutenant punched the man in the face, later recalling, “I had him on his back in an instant with the muzzle of a revolver at his temple and my hand on his throat.”

But after lighting a match, Cushing learned that the man on the floor wasn’t Hébert but Captain Patrick Kelly. The general had left for Wilmington hours before, and the noise Cushing had heard was the sound of Adj. Gen. W.D. Hardman clumsily escaping through a window. Confederate soldiers would soon be on the way.

Cushing tossed Kelly his pants and waved him to the door. Then the three Yankee officers, the Rebel captain and the two slaves who were a boat ride away from freedom headed quickly for the river. Behind him, Cushing could hear shouts of alarm as Rebels filled the street, “but like the old gent with the spectacles on his forehead, [they were] looking everywhere but in the right place.” Back in their boats, Cushing’s party was halfway home before Confederates at Smithville ignited signal fires to alert other bases on the river that Yankees were in the area. “At one [a.m.],” Cushing wrote, “I was in my cabin, had given my rebel dry socks and a glass of sherry, laughed at him, and put him to bed.”

Kelly didn’t get to sleep long; Cushing roused him for breakfast on the commanding officer’s ship. That afternoon the lieutenant sent Ensign Jones to Smithville under a flag of truce, in search of clothes and money to make Kelly’s stay in a Northern prison more comfortable. Ensign Jones was taken to the commander of the fort, a colonel also named Jones. After an understandably awkward beginning, the Confederate Colonel Jones showed his sporting side. “That was a damned splendid affair, sir!” he commented. The two went on to have an amiable chat, at the end of which Ensign Jones produced a letter from Cushing to General Hébert:

My Dear General:

I deeply regret that you were not at home when I called.

Very respectfully,

W.B. Cushing.

After that adventure, Admiral Samuel Lee, head of the squadron, gave Cushing an independent command to hunt blockade runners. What should have been an ideal assignment, however, turned out to be a waste of time. In five weeks Cushing captured nothing more than an abandoned British schooner full of rotting coconuts and bananas.

Then on the night of May 6, CSS Raleigh, an ironclad that had been built in Wilmington, emerged from the river and attacked the Union fleet. The sudden assault was launched after Confederate inspectors discovered that another ironclad based on the river, North Carolina, was riddled with shipworms, and declared it unsound. Raleigh’s commander launched his ship into battle because he didn’t want to risk suffering the same verdict, even though his vessel had never been designed to engage an enemy in open waters.

Raleigh couldn’t manage to close in on the Federal ships, and steamed haphazardly around the blockading squadron, firing occasionally without ever finding a target. During the confusion a blockade runner steamed through the Federal lines, but otherwise no damage was done. At dawn Raleigh returned to New Inlet, then disappeared over the bar back onto the river.

Cushing now envisioned a new mission: capturing Raleigh. “I feel very badly over the affair, sir,” he wrote to Admiral Lee in a melodramatic letter on May 9, “and would have given my life freely to have had the power of showing my high regard for you and the honor of the service by engaging the enemy’s vessels. If they are there when I arrive, I shall use the Monticello as a ram, and will go over her or to the bottom.’’ Lee soon endorsed the idea.

Cushing’s first step was to scout his adversary. On the evening of June 23, Cushing, Jones and Howorth as well as 15 volunteers armed with small arms and cutlasses took off in a cutter to find Raleigh. Entering the river with muffled oars, they passed Fort Caswell and the other outer batteries without catching a glimpse of the ironclad. Although Cushing had hoped the ship would be waiting, he determined it didn’t really matter. He was prepared to row to Wilmington if he had to.

The Federals traveled the first 12 miles—close to the half of the 30 that spread between the port city and their point of embarkation—half hidden by shadows. When they passed Fort Anderson, however, they found themselves in full moonlight, in view of sentries who immediately lit signal fires and took potshots at them. At first Cushing turned the boat around and rowed obliquely, feigning retreat, but as soon as a cloud slipped in front of the moon the lieutenant resumed his northward passage. Behind them the hubbub continued, as the Confederates searched for something that was no longer there.

By dawn the Union men were seven miles south of Wilmington when they pulled ashore and hid amid thick marsh grass and cattails. They spent the day resting and observing; Cushing counted nine steamers cruising past, three of them blockade runners. Later they saw Yadkin, the flagship of Flag Officer William Lynch, commander of all Confederate naval vessels in the Wilmington area.

Cushing figured that once night fell he would take the men up to Wilmington and explore its defenses. Just as they were about to embark, however, two small boats came into view hugging the shore. It turned out to be merely a fishing party—but one with some important news: Raleigh had sunk the day after its wild ride, running aground at high water. As the tide fell, its bottom split open. Now it was a toothless wreck.

Cushing displayed no disappointment, deciding that the opportunity to make mischief in the enemy’s backyard was the next best thing. With the fishermen as their guides, the Yankees headed farther north, toward Wilmington. Cushing managed to catalog the city’s defenses—earthworks, guns, iron-tipped spikes, three rings of obstructions in total, backed by a battery of 10 naval guns. At Cypress Swamp they located Mott’s Creek, and poled up the shallow stream to a point where it was crossed by a log road. They followed this rough path for about two miles until it intersected a turnpike, which one of the fishermen identified as the main connection between Fort Fisher and Wilmington. Lying in some tall grass there, they waited. The lieutenant figured that something of interest would eventually appear.

When a hunter passed by shortly before midday, the sailors jumped him. They quickly learned that he was in fact the owner of a general store about a mile away. Before they could question him further, however, a horseman clopped into view—a soldier toting a mailbag. In the face of eight or nine muskets and pistols, the man dismounted and surrendered his mailbag, which turned out to hold hundreds of letters full of information about the size of the garrison at Fort Fisher, the state of supplies and the deployment of its guns.

Soon the discussion turned to food, and Howorth suggested a daring plan. He would take the courier’s coat, hat and horse and go to the hunter’s general store, not far away. Flush with Confederate money taken from the mailbag, he would stock up for the group.

While Howorth went shopping—he eventually returned with chicken, milk and blueberries, the makings of a tasty picnic that, according to Cushing, “could not be improved in Seceshia”—Cushing and his men continued to detain passers-by, and eventually they were holding 26 people. Cushing figured that they would continue to sit there until the afternoon mail carrier bound for Fort Fisher came by, since he would likely be carrying the latest newspapers, always a good source of intelligence. But the courier apparently saw Cushing’s men first, because he abruptly wheeled his horse around and began galloping back toward Wilmington. Cushing pursued him for two miles but never caught up.

Once the mailman reached Wilmington, Cushing realized that Confederate authorities would learn of his foray. Rebels up and down the river would be on high alert.

Cushing ordered the telegraph wire cut and then led the group out of the swamp. At the river, he loaded his captives into canoes that were then tied to the back of his cutter. Around 7 p.m. Cushing’s little fleet headed to a lighthouse-occupied island in the river, where the Union lieutenant planned to leave the prisoners, confident they would soon be rescued. But as they reached the island, a steamer appeared on the horizon, seemingly headed toward them. Cushing and his men hid behind the boats; they were not detected, but he quickly changed his mind about what to do with his prisoners, cutting them loose in the canoes without sails or paddles. By the time they were rescued, he figured, any news they could pass on about Yankee raiders would no longer be a factor.

As the Union cutter headed for the mouth of the river in the predawn hours, it overtook a small boat, with four sailors and two women on board. Cushing’s boat was already overloaded, but he felt compelled to take the six captive. The prisoners were quick to taunt Cushing, however, telling him: “There are guard boats looking for you. You’ll never get past Federal Point. There’s 75 soldiers in a boat waiting for you.”

The moon had risen at that point, clearly illuminating the little boat in the wide, empty river, but Cushing was confident the tide was still in his favor. “I concluded to pull boldly for the bar,” he later reported, “run foul of the guard-boat, use cutlasses and revolvers and drift by the batteries in that way since they would not fire on their own men.” But just five minutes after starting for the channel, his plan failed; a large boat, certainly large enough to hold 75 soldiers, loomed ahead of them. Surrender was out of the question. “We determined to outwit the enemy, or fight it out.”

Fight it out seemed the most likely option. Cushing had closed to within 20 yards of the ship, intent on ramming it, when he saw three additional boats pull out from the bar on the left, and then five more from the right. Too many, Cushing realized, to overpower.

He quickly steered the boat to the right, toward the western bar. His men pulled hard and in perfect sync, opening precious space between themselves and their pursuers. The surprised Rebels fumbled with their oars and lost time turning. Had they thought for a moment, they might have realized what Cushing had already figured out: There would be no escaping that morning through the western bar. There was a strong southwest wind that would fill the passage with breakers too strong to surmount. He would be left there, his men straining at the oars and his overloaded little boat a perfect bobbing target for the guns of Fort Caswell.

But the Rebel pursuers chased the Yankee boat—and became all the more confused when it vanished. “Dashing off with the tide in the direction of Smithville,” Cushing reported, “…by my trick of steering the cutter so as to avoid reflecting the moon’s rays, caused the main line of enemy boats to lose sight of her in the swell.”

The Confederates were now chasing something they could no longer see. Cushing kept looking to exploit an opening, and as he felt the pull of the tide and current beneath him, he realized something important: He was at the point in the channel where the tide split. One channel led back to Fort Caswell, close to where his trip had begun, and one channel led past Fort Fisher to the Atlantic. Cushing called for one more quick turn, and the cutter caught the channel to Fort Fisher; his men then rowed like they were possessed.

Leaving the Confederate boats struggling to turn around, the Union vessel shot ahead. Borne by the current, it began opening up distance from the Rebel flotilla—30 yards, 50 yards, 100—all but vanishing against the horizon. There was a final plunge into the breakers off Caroline Shoals to thwart the gunners at Fort Fisher, and the expedition was over. Cushing hailed the steamer Cherokee, which towed the small boat back to Monticello. By midafternoon the Yankee raiders were again in their bunks, including Cushing, who had gone 68 hours without sleep.

Cushing’s raid on Smithville was certainly audacious. He brought back valuable intelligence that would influence Union operations in North Carolina for the rest of the war. Even more important, his account of his adventures helped convince his superiors that young Lieutenant Cushing was a very special talent—special enough to take on the ironclad Albemarle, the Confederates’ Roanoke River bully.

Jamie Malanowski is the author of Commander Will Cushing: Daredevil Hero of the Civil War. He writes from Briarcliff Manor, N.Y.