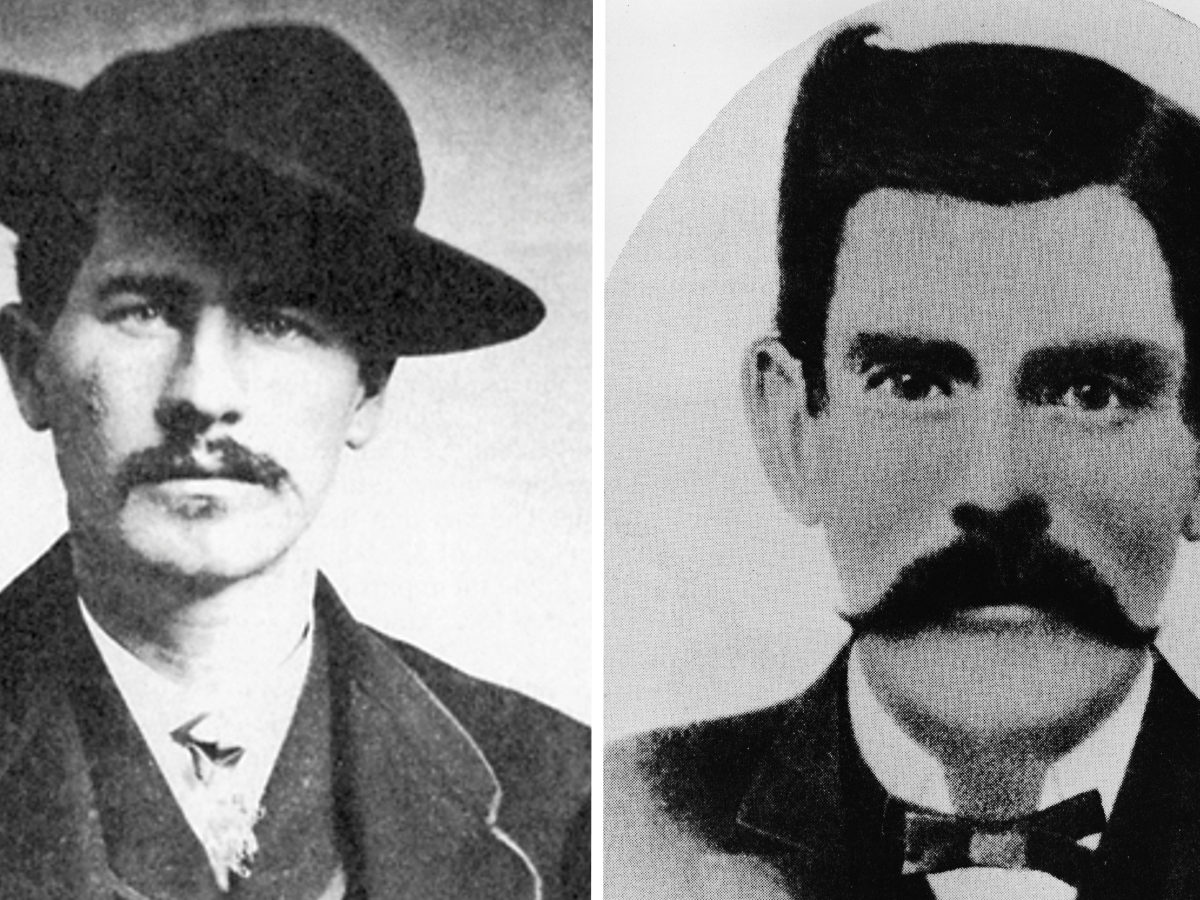

Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday, two of the American West’s most legendary figures, were unlikely friends (or were they?). Despite their differences in personality and backgrounds — one, a lawman; the other, a gunfighter — they remained loyal friends for much of their lives. After the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, their legend grew — along with an insatiable interest in their outsized personalities and tales of their adventures across the West.

HistoryNet RESOURCES ON Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday

Want to take a deep dive into the long friendship between Earp and Holliday? Aside from HistoryNet’s deep resources on the legendary duo, we’ve compiled a list of some of the best books and movies about the pair.

‘Tombstone: An Iliad of the Southwest’

(1927, by Walter Noble Burns, republished in 1999 with foreword by Casey Tefertiller)

This is the first book to give any real form to the life of John Henry “Doc” Holliday, whom Burns portrayed as a delicate-appearing Southern gentleman, but a man with no scruples save convenience and courage. It’s a compelling and influential portrait, even if the information Burns presented is incomplete, and he was mistaken on some key points. As for Wyatt Earp, Burns did not glorify him or apologize for him but explained him as a man who had no regrets. Burns’ view of the Wyatt-Doc friendship has a 19th-century edge to it, most likely reflecting his own values: “So these two friends stood side by side through good and evil report, through fortune and misfortune, through thick and thin, and back to back they fought in the swirling gloom of the final storm that threatened to engulf them.”

‘Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal’

(1931, by Stuart N. Lake)

In a book well received when first published, Lake portrayed Wyatt Earp as a hero—a portrayal that dominated the field for decades. Lake was plainly uncomfortable with Doc Holliday and his role in Earp’s life. Holliday was incompatible with the Earp he presented. How could a man as good as Earp be friends with a man as bad as Holliday? He concluded that Doc’s friendship for Wyatt was “of considerable significance” to any study of Earp and that “an accurate appraisal of Holliday” is essential to understanding Earp’s life. In Lake’s hands Doc comes across as a caustic, consumptive, nervy, deadly gunfighter devoted to Wyatt, while Wyatt’s friendship for him is justified in terms of Earp’s integrity, gratitude and loyalty to a man he thought was blamed for things he did not do. “Mind me,” Lake has Earp say, “Doc Holliday was no saint, and no one knows that better than I. But even the Devil is entitled to his due, and for reasons which will appear, I’d like to see Doc Holliday get his.” This accentuates Wyatt’s goodness, not Doc’s badness.

‘Doc Holliday,’ and ‘The Frontier World of Doc Holliday’

(1955, by John Myers Myers, republished in 1973; and 1957, by Pat Jahns, republished in 1979)

These two 1950s books are presented together here because each in its own way, though dated, offers particular insights and different perspectives on the friendship of Holliday and Earp. They represent the transition in the view of Wyatt Earp from the heroic image of Stuart Lake to the more critical view of the“debunkers” who dominated the 1960s. Myers filled in many of the gaps in Doc’s life. He believed Wyatt did not learn of Doc’s passing until 1895. “Doc and Wyatt had no more inclination to correspond with each other than do the average footloose males.” He believed Earp’s 1896 article was in part a tribute to Holliday. Jahns’ view of Doc was very different. She portrayed him as pleasant, in love with his first cousin, Mattie Holliday, embittered by his tuberculosis, and addicted to gambling and alcohol. Doc was drawn to Earp “as the very embodiment of the silent, manly personality.” She believed “neither one of them did the other any good,” but “the time came when Doc and Wyatt were always seen together, inseparable friends.” She saw Doc as weak, dependent and a terrible shot, and Wyatt as a self-absorbed, insecure exhibitionist. She wrote: “Two more completely misunderstood men never lived than Doc Holliday and Wyatt Earp. They probably never understood each other until one day in Pueblo, Colorado, in the late spring of 1882. And then they never spoke to each other again.”

‘Wyatt Earp: The Life Behind the Legend’

(1997, by Casey Tefertiller)

The friendship of Holliday and Earp puzzles Tefertiller. “The unusual friendship between Earp and Holliday can never be fully understood,” he writes. For him a key factor in the relation was Earp’s acceptance of Holliday as a man, without regard for his shortcomings or his disease. He presents Holliday as consistently loyal and appreciative of Earp’s acceptance. Wyatt became a real person with this book, not just a two-dimensional figure representing either good or evil. Tefertiller does not belabor the point of their friendship. He does detail the benefits and costs to Earp. He notes the quarrel in Albuquerque that led to their parting “was minor enough not to have impaired their friendship.”

‘Doc Holliday: The Life and the Legend’

(2006, by Gary L. Roberts)

The most frustrating part about trying to write a biography of Doc Holliday is that he left so few records of a personal nature. As a result we see him largely through the eyes of others, most of whom had agendas of their own. In the absence of personal information, an important tool is context, learning as much as possible about the times in which he lived. Context sometimes makes obvious what seemed obscure. The friendship of Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday is one example. Storytellers and historians have needed the latter to be a mystery in their efforts to justify or condemn Earp. But understanding 19thcentury attitudes toward male relationships takes away the mystery. The Damon–Pythias relationship between men the 19th century extolled rested upon a willingness to sacrifice for one another. Friendship was not about“good” and “bad” but loyalty. Finding more details and missing pieces is important, but sometimes one has to throw a wider loop rather than a tighter one to understand.

‘Gunfight at the O.K. Corral’

(1957, on DVD and VHS, Paramount)

It was right there on the movie poster: THE STRANGEST ALLIANCE THIS SIDE OF HEAVEN OR HELL. Producer Hal Wallis realized that none of the earlier movies on Tombstone had focused on the relationship between Earp and Holliday. This film presents Wyatt (Burt Lancaster) as an upright, honest, almost puritanical lawman, while Doc (Kirk Douglas) is a cynical, deadly man-killer, embittered by tuberculosis and indifferent to death. Texas cowboys and even the evil Clantons are subordinate to the Earp and Holliday friendship, which director John Sturges brings to the big screen in a storm of ambiguity. It plays loose with history, of course, and makes the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral the climax of the film, effectively ending the story with a showdown in which law and order triumph, and Earp and Holliday go their separate ways. Straight-shooter Earp is pushed over the edge by the murder of baby brother James. Holliday, the vicious killer, is then the person who tells Earp not to throw away his badge and the justice it represents. Ultimately, both men realize they need each other. Doc Holliday becomes a compelling part of the Tombstone story for the first time on film.

‘Warlock’

(1959, on DVD and VHS, 20th Century Fox)

Wyatt Earp is named Clay Blaisedell, Doc Holliday is called Tom Morgan, Tombstone is Warlock, and the O.K. Corral is the Acme Corral, but the genealogy of Oakley Hall’s novel and this film is unmistakable. It presents the Earp-Holliday friendship with refreshing insight. Blaisedell (Henry Fonda) is a professional town tamer and dime-novel hero brought in by local citizens to restore law and order against the threat of a gang of cowboys. He arrives in company with Morgan (Anthony Quinn), a sinister, unsympathetic character with a clubfoot (instead of tuberculosis), who immediately raises the question of why a man like Blaisedell would have him as a friend. The town soon begins to wonder whether they have made a mistake in hiring him. Morgan’s whole life is wrapped up in Blaisedell, the town tamer. When the marshal resolves to walk away from Warlock, Morgan calls him out. Blaisedell shoots down Morgan, who dies believing his “sacrifice” will preserve the Blaisedell legend. A darkly sinister mood permeates their friendship and the film.

‘Hour of the Gun’

(1967, on DVD and VHS, MGM)

John Sturges’ second run at Tombstone reflects some of the social changes between the 1950s and the 1960s and turns the earlier story on its ear in several ways. First, it begins with the O.K. Corral fight, and second, the relationship between Earp and Holliday is modified significantly. Earp, played by James Garner, remains the morally upright marshal, but the wounding of one brother and murder of another makes him cold and implacable. Holliday, portrayed by Jason Robards, remains a killer, but he takes on the role of Wyatt’s conscience. He is offended by Earp’s betrayal of his principles and constantly reminds him of his duty as a lawman. Earp’s descent into revenge changes the form and place of conscience. Holliday becomes more principled than the vengeful Earp. Garner’s portrayal of a brooding, quietly determined man is convincing. Robards’ Holliday is almost fatherly in his persistent role as conscience, but he maintains a sardonic wit and is resigned to the fate his disease assures.

‘Doc’

(1971, on DVD and VHS, MGM)

Pete Hamill’s Doc was one of a series of “dirty” Westerns popular in the early 1970s—not dirty in a pornographic sense, but dirty in an apparent belief that making every building appear to need a good cleaning and every actor appear to need a bath somehow enhanced a Western’s authenticity. This film dispenses with most of the assumptions of previous Tombstone movies. Wyatt Earp (Harris Yulin) is a brutal, cold-blooded man driven by ambition for power. Doc Holliday (Stacy Keach) is crude in this picture, and even when he questions his own conduct, he manages to revert to his nasty ways, rationalizing them because he’s dying. The only thing that makes Holliday seem redeemable is Earp.Wyatt would be laughable as a bumbling politician were it not for his corruption, lack of conscience and total disregard for life.

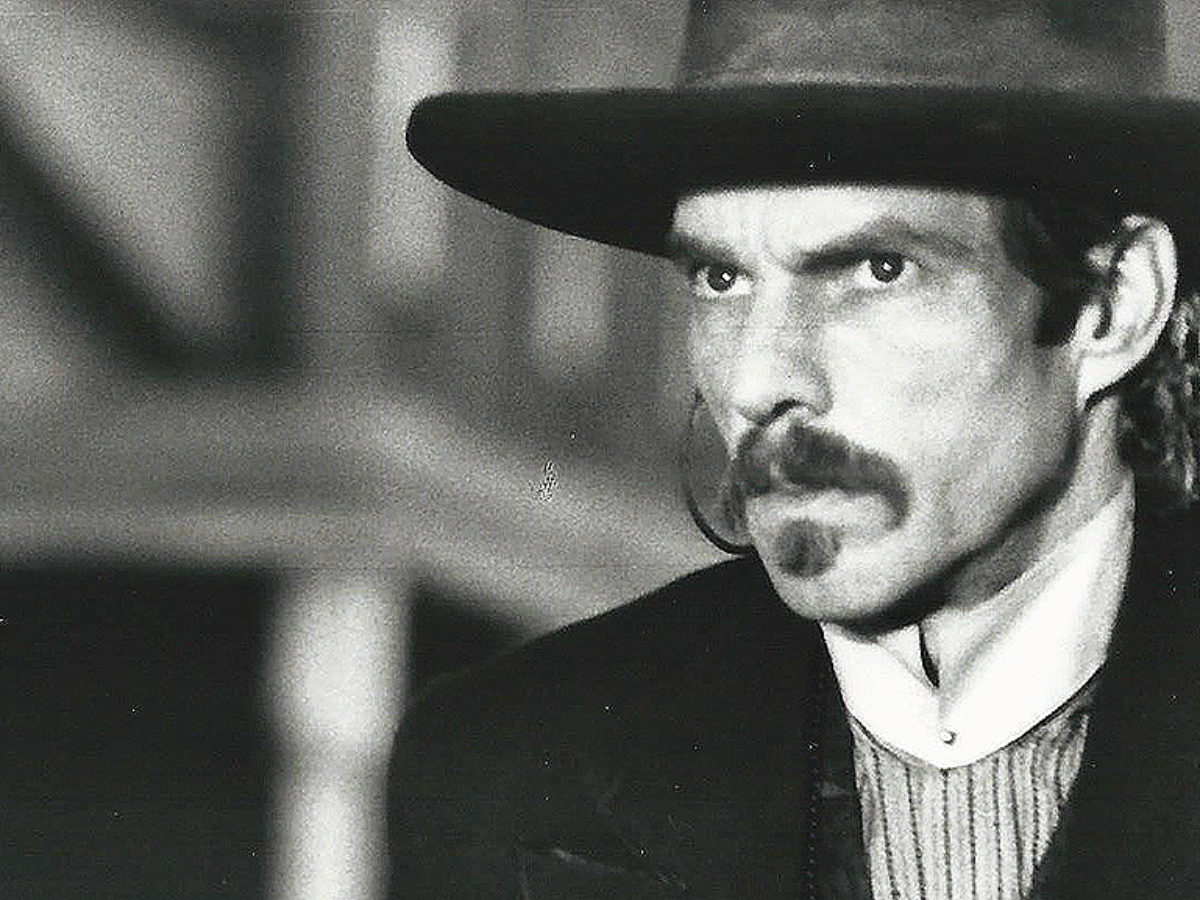

‘Tombstone’

(1993, on DVD and VHS, Walt Disney Video)

Arguably this film presents the most compelling view of the Earp-Holliday friendship. Wyatt (Kurt Russell) has the same controlled demeanor and confident air of other film Earps, but he shows emotions ranging from rage to tenderness and even uncertainty. He is clearly the most human Wyatt. He no longer wants to be a lawman but is drawn into the conflict with the Cowboys by brother Virgil (Sam Elliott), the moral conscience of the family. Doc (Val Kilmer) is worldly, sophisticated, charming, cynical and deadly. He plays the piano, drinks constantly and greets every circumstance with caustic wit. Wyatt says he likes Doc because “he makes me laugh.” Doc is resigned to his fate, but he is drawn to Wyatt because of the qualities of character from which Wyatt himself seems to be running. Though debauched, Kilmer’s Doc is oddly principled and steals the movie from Russell’s Earp because this “good badman” is more appealing to a modern audience than the vengeful Wyatt. At the end Doc is dying but encourages Wyatt to get on with his life. Wyatt says in parting, “Thanks for always being there, Doc.”

‘Wyatt Earp’

(1994, on DVD and VHS, Warner Home Video)

Kevin Costner is a cold, angry and dull Wyatt Earp. Though committed to family, by his own declaration Earp is oddly unemotional. The friendship between Earp (Costner) and Holliday (Dennis Quaid) is strangely one-sided, as if the dour Mr. Earp cannot allow himself to befriend anyone. When they first meet, Doc asks Wyatt,“Do you believe in friendship, Wyatt Earp?” Wyatt nods yes, and a bond is formed, though it is largely unspoken. Although crude, profane and ruthless, Doc is the more appealing character and looks the part of a man dying. Even though he assures Wyatt, “I’ll be there when you need me,” for most of the film Wyatt treats him like a burden. Doc seems closer to Morgan Earp, Wyatt’s younger brother. When Morgan is killed, Doc says tearfully,“I loved that boy,” while Wyatt stares out the window exuding fury rather than grief. Near the end of the film Wyatt clumsily manages to tell Doc he has been a good friend to him, which Doc brushes aside with a simple, “Shut up.”

Originally published in the December 2012 issue of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.