On June 17, 2021, President Joe Biden signed legislation officially establishing Juneteenth as a federal holiday commemorating the end of slavery. It was, historically speaking, a long time coming.

Recommended for you

Dubbed Juneteeth, a combination of the words “June” and “nineteenth,” the day was originally celebrated by formerly enslaved peoples in Galveston, Texas, shortly after the Civil War. Official news ordering the freeing of slaves had arrived late in the Lone Star state, just two months after the surrender of Gen. Robert E. Lee and two years after President Abraham Lincoln enacted the Emancipation Proclamation into law on Jan. 1, 1863.

On June 19, 1865, Union army Gen. Gordon Granger arrived in Texas with federal troops in tow to deliver the announcement titled General Order No. 3. The order stated that “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.” Those words would release approximately a quarter of a million Blacks living in the state.

Since then, the commemoration of that day — in all its forms — has grown around the United States.

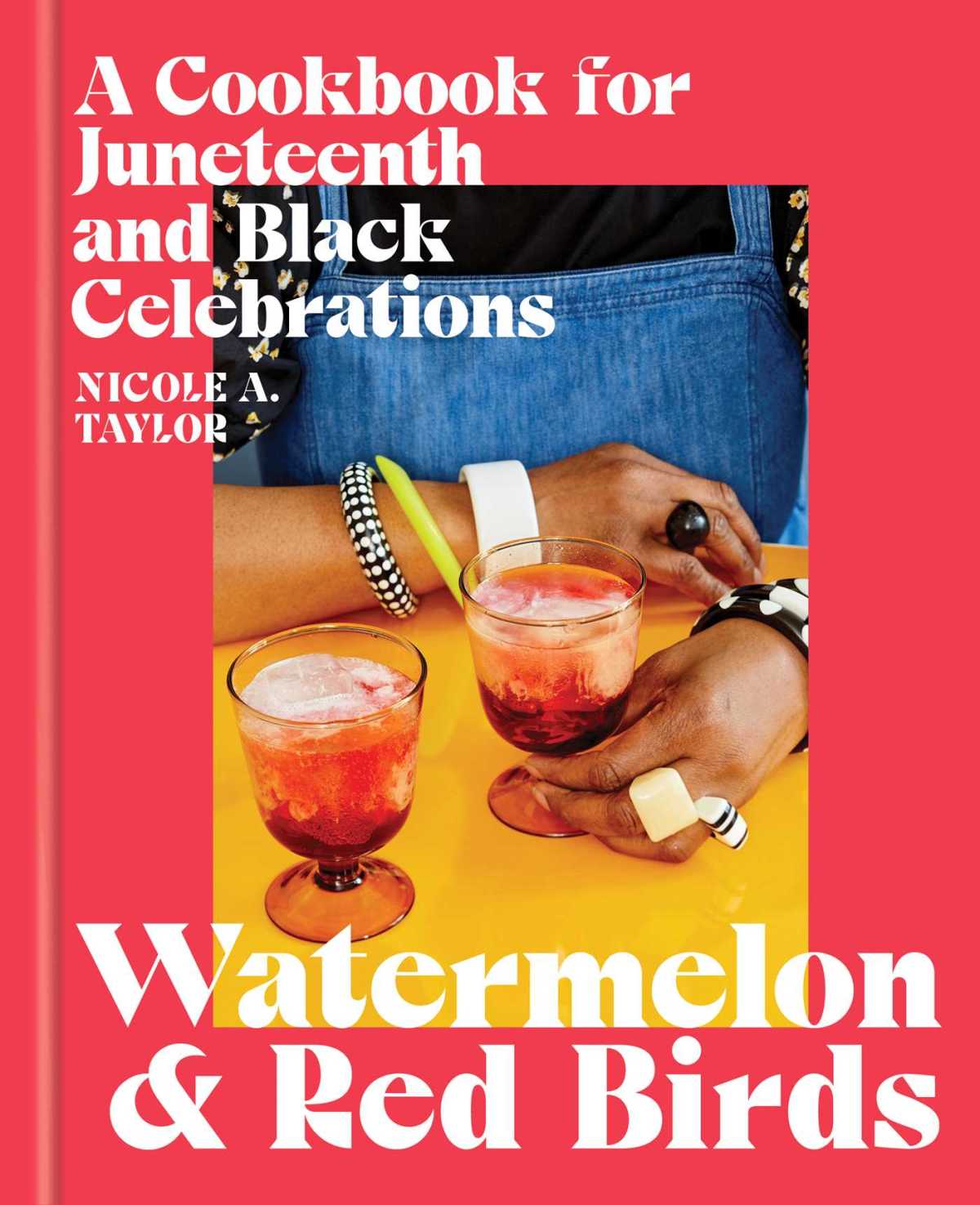

HistoryNet recently spoke to James Beard Award–nominated food writer and author Nicole A. Taylor, whose latest cookbook, “Watermelon & Red Birds” is the very first compilation of recipes dedicated to Juneteenth.

She also discusses why the humble potato may just be the most diverse — and comforting — food in the game.

Watermelon & Red Birds

Book subtitle or blurb goes here.

by Nicole A. Taylor, Simon & Schuster, May 31, 2022

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

In a recent article you wrote for the New York Times you talk about “U.S.D.A. Prime liberty in all its bitter sweetness.” Can you talk about the inspiration behind your latest Juneteenth cookbook and all of its — and your — quieter moments of triumph?

That sentence is one of the first things I wrote when I started the book proposal back in 2019. When I write wrote that I wanted to convey two things and that is: the systems that we have in America — and how Black people are a part of those systems — or how we crave to be recognized and have equality in those systems. For us everything is bittersweet.

Juneteenth becoming a national holiday was a triumph but also a bittersweet moment because we were, and are still, in the midst of having questions about the Voting Rights Act, questions around gun violence. So yes, Juneteenth became a national holiday, but it was bittersweet for sure.

What does the color red represent on Juneteenth and how did you incorporate it in your food? Can you speak on the history of Black cuisine the relationship to the Black diaspora?

Many scholars and historians talk about red being the color of royalty, red being a color that’s tied to that African spirituality. You see in the Black Liberation flag; there’s a color red. Red is a very powerful color.

I mean listen, in my everyday life, when I put on that red lipstick you can’t tell me nothing! [Chuckles]

So, when you look at Juneteenth foods you see red being very bright, vibrant. I think there’s a lot of reasons. I think it’s also because of the summer months. You have a lot of red vegetables and fruits. But more specifically, the color red and the red drink is a drinking ritual that connects Black people across the African diaspora. From Senegal, to Martinique, to the Bronx, New York. Black people at celebrations typically have a red drink. And that goes back to or is linked most commonly to a West African drinking tradition. In Senegal, Bissap is the national drink and it’s a hibiscus pods and leaves which turn red and when you combine it with water. That tradition I like to say, was carried over during the transatlantic slave trade, and so generations later the red drink still shows up.

You see it in Martinique. You see it in Brazil. you see it in Jamaica. In Southern plantation cookbooks, you see the writer speaking about plantation owners saying that enslaved people at celebrations would have red colored beverages like strawberry liquors, cherry syrup and strawberry lemonade. So that tradition lives on and lives on in 2022. I didn’t realize that the red punch that would always be at the table really connected to Black folks all over the country.

The State Fair of Texas has long been hailed as a celebration of Texas culture, tradition, and of course, food. But for much of its history it was segregated. How did Black chefs thrive despite this? And how have these traditions been carried on?

First of all, I gotta say that I’m a master home cook. I’m not a food scholar but for this book I dug a little bit deeper and I referred to my friend and colleague, Adrian Miller, because he has a whole chapter in his James Beard award-winning soul food book where he talks about the red drink.

I think one of the other things that I learned was from one of my colleagues, Adrienne Lipscomb. She wrote about the Emancipation Cake, so my peach plum cake ties into the tradition of people making this emancipation cake. So that was a beautiful discovery.

The Texas State Fair and finding out that bit of history was not on purpose. I knew that I wanted to do a chapter titled Festivals and Fairs because I think for many people who have been celebrating for generations, they’ll have their drinking party in the house but they also, before the Juneteenth party, go to the parade.

And at the parade not only will you see the horses, the community groups and bands, there will be food and long lines of folks waiting for funnel cakes and corn dogs. Throughout the whole chapter you see very classic Americana food, but also food that speaks to Texas in a real way, like the Frito nachos that I have, which is very much a Texas thing. You’ll see Mexican culture, or Tex-Mex culture, or Latinx people and their food in that chapter.

But getting back to the core of your question about the vendors. I honestly was more fascinated by the woman [Juanita Craft] and her archives in Dallas, Texas. This one woman is credited in leading the way to desegregate the state fair. Her papers are published and available in the public library.

I was more fascinated with how this fair transformed this community for good and bad. Restaurant culture, fine dining culture is great. And I think there are a lot of Black chefs who have succeeded. But we know through W.E.B. DuBois and others that there were middle class, upper-middle class Black people who made their livings being caterers. And so when I think about Black food vendors I think about Black caterers and Black people who didn’t have brick and mortar businesses yet they were still able to make extra money, or that was their main living, selling corndogs, barbeque, fried fish, or funnel cakes at fairs and festivals from Texas to Atlanta to New York.

I always like to end interviews on a somewhat lighter note, so what is your favorite-go to recipe when you just want to relax and unwind?

Crazily, I’m not going to say anything fancy. It’s french fries.

I have a french fry recipe in the book, but it’s not just your typical fries. It’s wavy fries with lemon pepper seasoning, which is homemade. I like to go the extra step right when I’m making or eating french fries. It’s the food that I return to time and time again.

I know you were expecting something fancy!

Not at all! I like to slap an egg, really anything, on fries.

Exactly. There are so many ways to elevate the humble potato. When I think about the potato and fries I think about these three tier hanging wire baskets that were in my childhood home. There would be potatoes in there always. It was never empty. It was like “okay, if you get too hungry you can make some potatoes.” Maybe that’s why I’m obsessed with the potato.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.