WHILE PATROLLING the beaches of Ocracoke Island, North Carolina, on May 14, 1942, two young Coast Guardsmen glimpsed an unusual shape bobbing in the surf. They stopped their truck to investigate and one of them, Arnold Tolson, took off his shoes and waded into the ocean, where a lifeless body tossed among the waves.

The Coast Guardsmen retrieved the corpse from the water and placed it in the bed of their truck. It belonged to a man in his late 20s with a black beard, wearing a dark-colored uniform and a blue turtleneck. Before the young sailors could reach their Coast Guard station with news of their gruesome discovery, a man flagged down their truck as they sped across the island and through its small village. He had spotted another dead young man in the tide wearing a similar dark ensemble and informed the Coast Guardsmen of the body’s location.

Identifying the waterlogged bodies proved straightforward once they were laid out at the Coast Guard station. Inside the bearded man’s pocket were papers, including a bank book, that revealed his identity: Sub-Lieutenant Thomas Cunningham, 27, a British Royal Navy volunteer reservist. The second man, who wore a shirt with his name written inside, turned out to be another Royal Navy sailor, 24-year-old telegraphist Stanley Craig. Both belonged to the crew of the HMT Bedfordshire, a British armed trawler that had arrived in North Carolina from England around a month and a half prior.

The Bedfordshire hadn’t been officially declared missing. But the two dead men, likely casualties of one of the distant offshore explosions frequently heard by the North Carolina barrier island’s residents, were a strong indication the ship would not be returning to its homeport. Home, though, would come to Ocracoke’s quiet shores. Long after the war’s end, a small parcel of North Carolina became British soil, in memory of the Bedfordshire’s crew.

IN THE FOUR MONTHS PRIOR to the discovery of the bodies, German U-boats had sunk some 150 ships off the U.S. East Coast—nearly one a day, many of them transporting fuel oil and freight. Because the U.S. Navy’s gunships and destroyers were off fighting in the Pacific or escorting convoys across the North Atlantic to England, important ports were left vulnerable. Compounding the danger, mandatory blackout regulations for coastal cities and towns would not be enforced until mid-1942, making unescorted merchant ships easy targets against the illuminated horizon.

U-boat crews dubbed this shooting gallery off the East Coast the “Second Happy Time,” a reference to the initial “Happy Time”—a victorious streak from July-October 1940 when U-boats sank 282 Allied ships while losing only a half-dozen subs. On the defensive, American sailors and antisub aircrews grew increasingly skittish, judging from daily incident reports that detail frenzied responses to the threat as they attacked anything that remotely resembled a submerged U-boat, whales included. Meanwhile, beaches from Maine to Florida were awash in wreckage and oil that intrepid swimmers scrubbed off their skin with kerosene. Ships transiting the coast frequently picked up shipwreck survivors in life rafts from vessels that not long before had vanished beneath the waves.

In its April 1942 war diary, the navy’s Eastern Sea Frontier Command, responsible for some 1,400 miles of coastal waters from the Canadian border to Jacksonville, Florida, reported that the Germans had sunk 24 vessels—mostly tankers and freighters—in the preceding 30 days. “Thus, once again, the Eastern Sea Frontier was the most dangerous area for merchant shipping in the entire world,” the report stated, chalking American losses up to “inadequate strength.”

The outlook for May appeared better, though—thanks in part to Britain. The Royal Navy had just sent over 24 fully-crewed armed trawlers—including the Bedfordshire—to conduct antisub patrols and accompany convoys of merchant ships. American officials were cautiously optimistic that these loaned vessels and crews could help mitigate the U-boat threat.

That spring, the Bedfordshire, based at Morehead City, North Carolina, began patrolling shipping lanes off Hatteras Island in North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Trawlers of its ilk were cramped and temperamental; while armed with machine guns, four-inch deck guns, and racks of depth charges, they had originally been built for commercial fishing. Fish holds often doubled as crew messes and crewmembers shared the dirty work of shuttling coal for fuel. Still, the Bedfordshire’s British and Canadian sailors enjoyed some comforts—including collecting their traditional dram of rum around 11 a.m. each day. Cunningham, who was the Bedfordshire’s second-in-command, wrote home about friendly townsfolk and kept the tone of his letters to his pregnant wife, Barbara, upbeat.

Onshore in Morehead City, where the crew frequently stopped to stock up on provisions, they pursued the typical activities of young men: carousing, drinking, and wooing women. Some Bedfordshire sailors enjoyed an evening on the town on May 10, 1942, before the call came to weigh anchor the following afternoon. Four crew members ultimately never made it aboard—including stoker Samuel Nutt and cook Richard Salmon, who found themselves in jail following the previous night’s alcohol-fueled antics. But the Bedfordshire and its remaining crew set off to sea, escorting a convoy to Hatteras before joining another British trawler, the St. Loman, to search for a U-boat just east of the island’s shipping lanes. It would be their last mission.

Cunningham was likely on duty the night of May 11-12, in charge of a skeleton crew that may have included telegraphist Craig, a sonar technician on the alert for submarines, and several lookouts. The hunters were unaware that they made tantalizing prey to a watchful crew aboard a nearby U-boat.

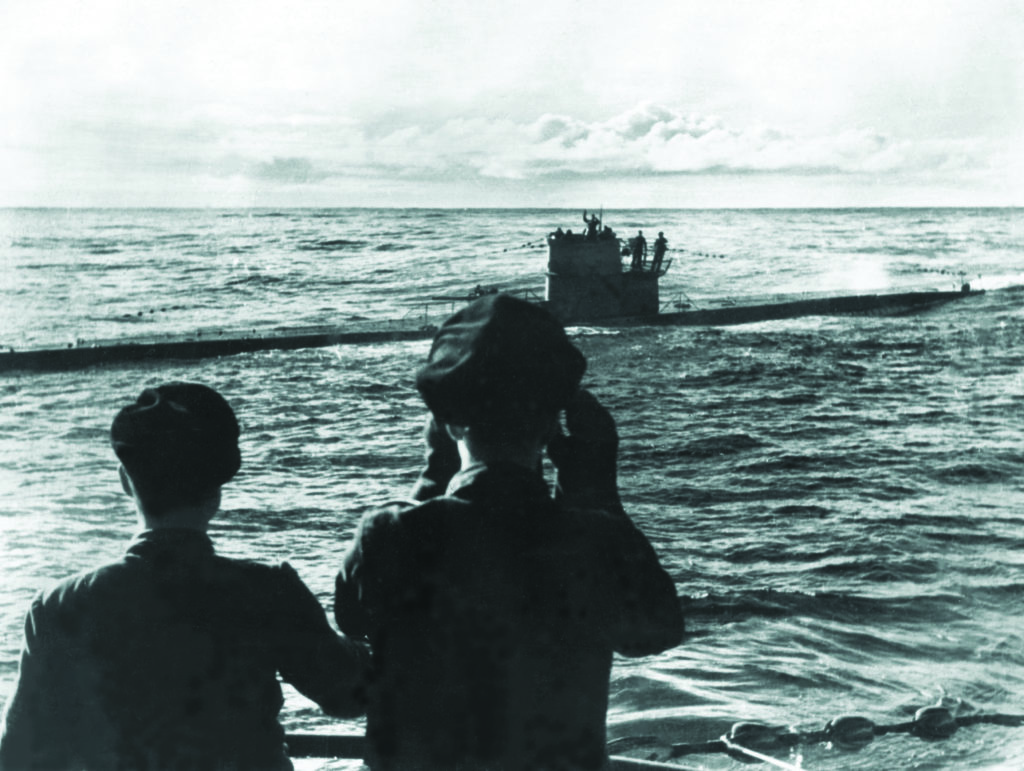

GERMAN U-BOATS like U-558—a Type VIIC, with a range of nearly 10,000 miles—were capable of crossing the Atlantic, spending several weeks patrolling the American coast, and returning to port in Europe without refueling. When U-boats returned to their home pens, they flew flags from the rigging to show how many ships they had sunk; Nazi propagandists broadcast these successes to offset disappointing war losses in other theaters. Successful crewmen and commanders found themselves in the spotlight as German towns adopted individual U-boats and hailed their crews as heroes. Naturally, the men turned this attention into a competition to sink the most tonnage and collect more accolades than their peers. This competitive drive was surely turning to frustration for the 44 crewmen aboard U-558 on May 11, 1942. They’d been at sea for a month on their seventh war patrol without so much as firing a torpedo.

U-558 had left occupied France on April 12. At its helm was Kapitänleutnant Günther Krech, 27, a focused yet cheerful man who commanded his crew’s respect. The Kriegsmarine initially routed the U-boat to Bermuda before assigning it to hunt Allied ships off the Outer Banks. U-558’s crew was aware that other submariners had found plentiful targets there, and they undoubtedly yearned to add to their tally from previous missions. Still, they had spent their first days off North Carolina’s coast sitting on the ocean bottom during daylight hours and, at night, fruitlessly patrolling a nearly 200-mile swath of shipping lanes.

On May 7, a destroyer had passed nearby during daylight, headed toward Cape Lookout, but Krech declined pursuit. He determined the situation was “no shooting opportunity” because the ship was out of range. Then, two days later, a tantalizing convoy had slipped through the crew’s fingers. The U-boat waited several hours as night approached to pursue the group of ships—three steamers and four tankers, protected by a Coast Guard cutter and two gunships—with plans to catch them near Cape Lookout, at the southernmost point of the Outer Banks. At 6 p.m. the submarine surfaced to intercept the convoy, but had to dive when a large patrol plane flew overhead. By 9 p.m., the convoy had vanished into the fog and darkness.

Early on the afternoon of May 11, U-558’s luck finally turned after a fashion when it came across two enemy targets—the trawlers Bedfordshire and St. Loman on patrol—and dove to hide. When dusk fell, the vessels were still within sight. Krech maneuvered U-558 to go on the attack and gave the command. Two torpedoes streaked through the water toward the Bedfordshire—an unusual “double shot” that expelled torpedoes from two tubes simultaneously, with the potential to result in a decisive and spectacular explosion. Several moments later, the crew realized both torpedoes had missed their mark.

U-558 lined up another shot. This time Krech was more deliberate, closing the distance to his target by nearly half and firing just one torpedo broadside at the trawler. Thirty-six seconds later, the commander and his crew witnessed an enormous explosion through the periscope as the underwater missile struck just behind the trawler’s bow. The Bedfordshire’s stern dramatically popped above the water as the ship began to sink.

The U-boat then turned its attentions toward the St. Loman, pursuing the second trawler until a single missed torpedo shot prompted the ship to fire star shells that lit up the night sky. Spooked, U-558 fled the scene—leaving well behind it the Bedfordshire and its doomed crewmen, as the trawler’s wreckage settled onto the ocean floor in the early hours of May 12.

TWO DAYS AFTER Cunningham’s and Craig’s bodies washed ashore, the Eastern Sea Frontier Command’s Enemy Activity and Distress Report recorded their deaths along with another beachside find: an empty life raft. Noting that the Bedfordshire hadn’t been heard from since May 11, officials recategorized the ship as “missing and possibly sunk” in their daily log. Four other bodies were later recovered—one identified as and the others presumed to be Bedfordshire crewmen—but 31 crewmembers remained lost, many likely trapped aboard the wrecked trawler, which sits today beneath 105 feet of water, 17.2 nautical miles offshore of Cape Lookout.

Rallying to do right by Cunningham and Craig, an Ocracoke family donated a tiny burial plot adjacent to their own cemetery; wooden “sink boxes”—submersible, human-sized enclosures used for waterfowl hunting—served as makeshift coffins. In a poignant twist, the British flags draped over the caskets before burial had been provided by Cunningham himself; he had lent them to Naval Intelligence officer Aycock Brown just weeks before his own death, to honor the victims of another torpedoed British boat, the tanker San Delfino. Two of the other recovered bodies, never identified but also wearing Royal Navy uniforms, were buried with care alongside Cunningham and Craig. (The remaining two bodies, including identified seaman Alfred Dryden, were buried in other local cemeteries on the Outer Banks.)

“If I should die, think only this of me / That there’s some corner of a foreign field / That is forever England.” ✯

Today, the 2,290-square-foot graveyard sits in the heart of Ocracoke Village, surrounded by trees and a white picket fence; a British naval flag billows overhead in the salty breeze. Each May, Ocracoke Coast Guardsmen, Royal Navy members, and dozens of local citizens hold a ceremony at the site, reading the names of the Bedfordshire’s 37 deceased crewmembers aloud, in memory of them and their sacrifice.

A commemorative plaque explains that in 1976 the North Carolina State Property Office granted a perpetual lease for the gravesite to the United Kingdom. Thanks to this, Cunningham, Craig, and their two crewmates will rest forever in British soil. Quoting poet Rupert Brooke’s World War I poem, “The Soldier,” the plaque reads:

This article was published in the April 2020 issue of World War II.