What’s this striking art deco building doing in the middle of the nation’s most important Civil War battlefield?

By the time construction began on the National Guard Armory on West Confederate Avenue in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in January 1938, the federal Public Works Administration had already overseen hundreds of such projects around the United States. The PWA, established in June 1933 as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, had spent the modern equivalent of $85 billion on 34,000 public works projects, including such well-known constructions as the Hoover Dam in Nevada, the Lincoln Tunnel and Triborough Bridge serving New York City, segments of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and the Overseas Highway in the Florida Keys. The goal was to help alleviate the social and economic ills of the Great Depression by creating jobs and purchasing power for construction workers and those working in factories producing the materials needed for the projects.

Unlike such Depression-era projects as the Civilian Conservation Corps, which generally used its own employees, the PWA typically farmed out its work to local contractors. C. S. Williams of Dillsburg received a $41,321 contract to construct the armory building. Other contractors included Alfred LeVan of Gettysburg (heating and ventilating), A. G. Crunkleton of Greencastle (electrical), and B. O. Poff and Son of York (plumbing). Pennsylvania’s Armory Board sent proposals for a $2 million ($30 million in 2021 dollars) construction program as a part of the state’s $56 mil-lion PWA building program. The Gettysburg Armory was to cost $40,000 ($600,000 in modern terms).

The Borough of Gettysburg purchased land on West Confederate Avenue from Calvin Gilbert, a Union Civil War veteran, for $900. Gilbert had served in the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment and after the war had operated a foundry in Gettysburg that built gun carriages for the cannons placed all around the battlefield. The proposed location of the armory wasn’t a site of heavy fighting during the Battle of Gettysburg, but it was used for part of Confederate corps commander A. P. Hill’s gun line. The batteries there were among the primary threats to the Union artillery on Cemetery Hill, center of the famous Union “fishhook” defensive line on the second and third days of the battle.

John B. Hamme, an architect in York, Pennsylvania, was selected to design the armory. Hamme had founded his firm in 1900 and run it until 1945, when he turned it over to his son, J. Alfred Hamme. While many of the armories and other buildings constructed by the PWA (including the nearby Waynesboro Armory) were done in a spare, modernistic style that has come to be known as PWA Moderne, Hamme designed the Gettysburg Armory in a more flamboyant art deco style. The building’s distinctive art deco characteristics included vertical emphasis, straight and smooth lines, streamlined and sleek forms, hard edges, waffle–pattern glass, and chevron arrangements. Its architectural merit and historic value later earned it a spot on the National Register of Historic Places.

Construction began on January 10, 1938, shortly after a groundbreaking ceremony presided over by the commander of the Pennsylvania National Guard and the president of the county board of commissioners. The armory measured 96 by 61 feet and was built with nearly 63 tons of steel, 65,000 bricks, and 20,000 concrete blocks. It was originally scheduled to open by July 1938, in time for the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. The Guard units were impatient to move into their new quarters from their accommodations on the third floor of the American Legion building, but delays continued to plague the project. Another revised August 6 deadline came and went, and further delays pushed the occupation date of the armory to March 1939.

Adams County, where Gettysburg is located, has a long history of national service. Its volunteer units have served in every war since 1800. During the Civil War, county companies served in the 90-day 2nd Pennsylvania (which answered President Abraham Lincoln’s first call for volunteers) and the three-year 30th, 74th, 87th, and 101st regiments. Another local unit, the 26th Emergency Militia, was formed in response to Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s June 1863 invasion of the North and had a brief scrap with Major General Jubal Early’s division a few days before the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1–3.

In 1870 the state’s militia became, officially, the National Guard of Pennsylvania. Its units were formed into a single division (the 28th) in 1879, making it the oldest continuously serving division in the U.S. Army. Gettysburg’s National Guard unit joined other Pennsylvanians of the 28th Division and served in the U.S. Army’s 1916–1917 expedition against the paramilitary forces of Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa. The 28th then deployed to Europe during World War I, where it saw particularly fierce fighting at Château-Thierry. The 28th suffered nearly 14,000 casualties and earned the distinction of “Men of Iron” from General John J. Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces. The opposing Germans termed it the “Bloody Bucket” regiment because of its red keystone insignia.

Through all this time, Gettysburg’s National Guardsmen had a superb drill field but no home of their own. Although Gettysburg National Military Park wasn’t created until 1895, local residents had begun preserving the “hallowed ground” almost as soon as the armies left. The park was meant to protect the land and to mark combatant lines. But national military parks were also intended to help train soldiers and future military leaders. Gettysburg was used for summer maneuvers of the state’s National Guard troops even before the War Department took over management of the land, which was subsequently used as a tank training camp, known as Camp Colt, during World War I.

While its main function was to support the local National Guard unit, the new armory was also made available for community uses. It housed public meetings, square dances sponsored by the local 4-H Club, and basketball games for local high schools as well as Gettysburg College.

When World War II began, the 28th Division again went off to war. Gettysburg’s local unit, Company E of the 103rd Quartermaster Regiment, was inducted in February 1941, 10 months before Pearl Harbor, and left for a year’s training at Fort Indiantown Gap, the state’s National Guard training center. The 28th arrived in Europe on July 24, 1944, just as the Allied breakout from Normandy, known as Operation Cobra, was beginning. The regiment was involved in all the European campaigns to V-E day, receiving five battle stars and taking 15,904 battle casualties (equivalent to nearly its full strength).

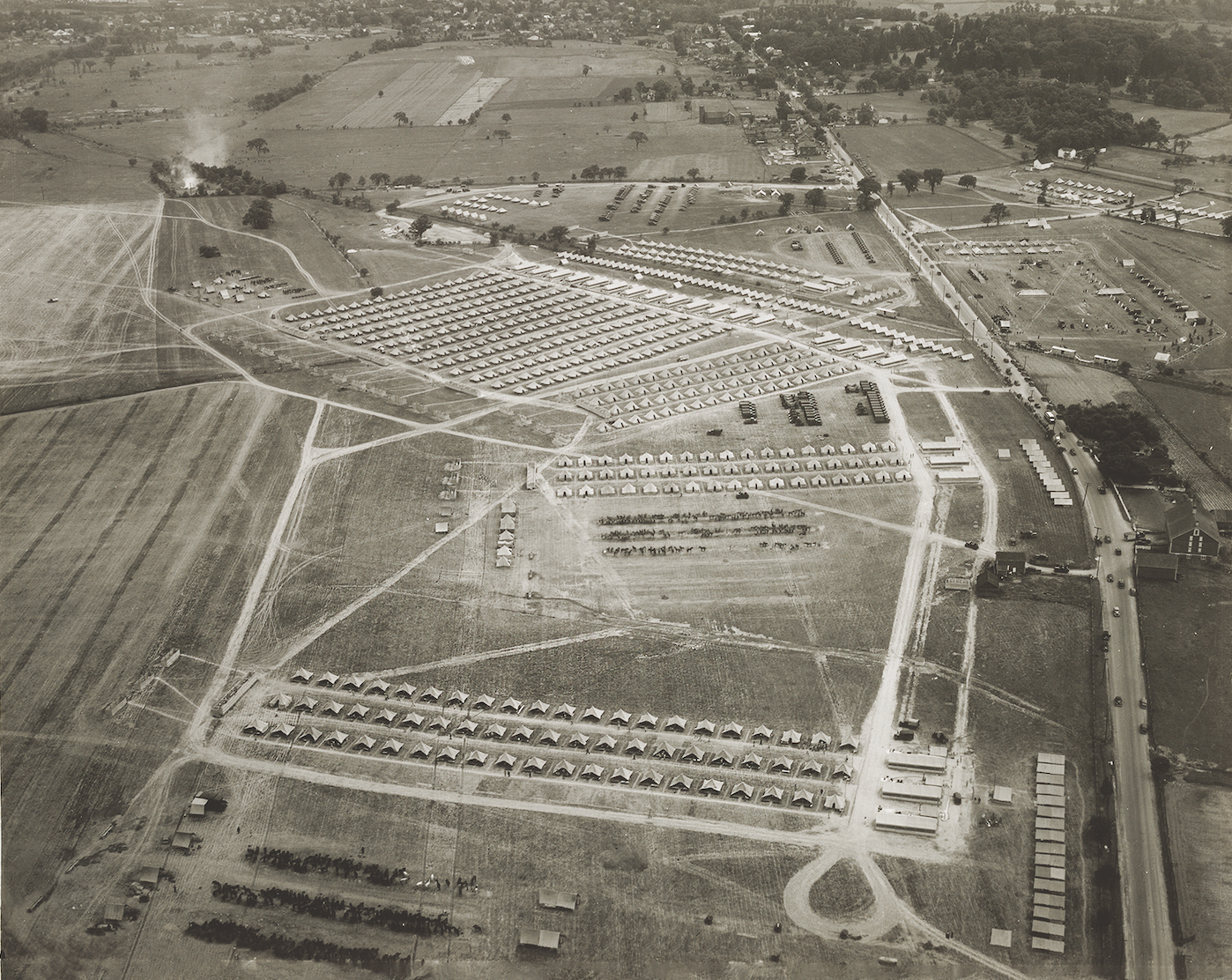

The Gettysburg Armory was put to an unusual use while the 28th was deployed in Europe. In mid-June 1944, a temporary POW camp was established on the Gettysburg battlefield. The tent camp was on the west side of Emmitsburg Road, just south of the Home Sweet Home Motel. (The motel was demolished in 2003.) The camp was built by 50 German prisoners, drawn from the first 100 German prisoners temporarily housed in the armory while they constructed the camp. This was not a high-security camp; the 400 inmates were used as labor in local orchards and fruit- and vegetable-packing plants. Any farmer, orchard owner, or packer could apply to the local employment service for POW labor.

The German POWs in Gettysburg worked at 17 farms, 14 canneries, 3 orchards, a stone quarry, and a fertilizer plant. Employers paid them $1 an hour, with 90 cents going to the federal government and 10 cents to the prisoners in the form of coupons that they could use at the post exchange. In the last five months of 1944, the government took in $138,000 for the use of the POWs. In the cold-weather months, the prisoners were housed in barracks at Camp Sharpe, in the McMillan Woods on the battlefield.

The prisoners were welcome additions to the labor force; Adams County suffered chronic labor shortages after most of its young men went off to war. The prisoners were guarded at all times while working. A few attempted escape, but for the most part they were satisfied with their relatively soft and safe life. The prisoners particularly enjoyed the switch from vegetable-canning season to harvesting cherries and apples, which they could eat while they worked and smuggle leftovers back to camp in their pockets. In fact, some local newspapers published complaints that prisoners were “well fed and living the good life while brave Americans were neglected and starving.”

Although there were strict rules barring fraternization between locals and the POWs, these rules were pretty much ignored. The prisoners were naturally regarded as a curiosity in the community, and one army officer complained that local women were loitering around the camp. A York newspaper reported that “many interested spectators lined the fences Sunday to watch the German boys playing a Teutonic type of handball.” A Gettysburg resident, John Augustine, who was 11 years old in 1944, recalled seeing German prisoners sitting on the steps of the armory strumming guitars, playing cards, and drinking beer. (They made a home brew with sugar stolen from the canning factories.) Joan Thomas, daughter of camp commander Captain Lawrence Thomas, said the prisoners played soccer constantly in their off-time and sang opera at night in their camp.

Local residents worked alongside the POWs in the fields and factories. Stella Schwartz, then a Goucher College student working at the B. F. Shriver Canning Company in Littlestown, remembered that the prisoners offered to exchange personal belongings such as much-coveted pilot’s wings in return for science and math textbooks. Many Gettysburg residents commented on the prisoners’ mechanical aptitude and work ethic, and Marcus Ritter, the manager of the Knouse Foods plant, noted that the POWs “learned English faster than [the locals] learned German.” Some prisoners even claimed that they had surrendered so that they could “get a chance to see America.”

The last German escape attempt occurred after the war, in January 1946, when POWs Hans Harloff and Bernard Wagner slipped under the barbed wire at the work camp on Emmitsburg Road and hid at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Byron Cease, whose daughter, Pearl, had worked with one of the men at a canning factory in Orrtanna and secretly exchanged notes with him. The Ceases were arrested for helping the escapees, but the judge suspended their sentences, ruling that, as the war was over, a prison term “would serve no good purpose.” Harloff and Wagner said they had escaped because they liked America and wanted to see more of it instead of returning to Germany. In the years after the war, local newspapers reported the return of a number of former prisoners to visit the site of their incarceration.

Following the war, the Gettysburg Armory remained in use for more than 70 years. National Guard units trained and deployed more than a dozen times for overseas conflict, natural disaster cleanups, and events such as diplomatic summits and a papal visit. The Gettysburg National Guard unit deployed overseas one last time from the armory in September 2008. Bravo Battery of the 1st Battalion, 108th Field Artillery went to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and Fort Polk, Louisiana, before spending eight months in Iraq. Bravo Battery was welcomed home in September 2009. In 1995 the nearby Waynesboro armory was shuttered, and its tenants were consolidated with the Gettysburg Armory’s. A decade later, the Gettysburg facility was shuttered, and a new, much larger armory was constructed at South Mountain, Pennsylvania. The larger facility was needed to accommodate Battery Bravo’s new role in support of the 56th Stryker Brigade Combat Team.

In January 2014, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania donated the Gettysburg Armory and the three-plus acre property to the Gettysburg Foundation, the organization that built and operates the Gettysburg National Military Park visitor center. On August 29, 2015, the foundation and park opened a facility in the garage on the armory property to perform maintenance on the roughly 400 gun carriages around the park. Authorities have discussed possibly using the armory for the park’s education program or as a police substation, but for now the building sits empty of everything except its memories. MHQ

Leon Reed, a retired defense consultant and U.S. history teacher, is a writer and publisher in Gettysburg. Eric Lindblade is a licensed Gettysburg battlefield guide and a cohost of the Battle of Gettysburg Podcast.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2021 issue (Vol. 33, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Behind the Lines | Arms and the Men

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!