Last time out we were discussing the Winter War, the conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland during the winter of 1939–40. As we saw, a combination of Soviet bullying and Finland’s refusal to be bullied had typical consequences for this era. Soviet demands gave way to threats, and when the talks faltered, Soviet foreign minister Molotov had the last word: “Since we civilians don’t seem to be making any progress, maybe it’s the soldier’s turn to speak.” Just days later, on November 30th, a massive Soviet force invaded Finland while bombers of the Red Air Force ranged deep inside the country.

Expectations are the key here. Just a few months earlier, German Panzer columns had invaded Poland, slicing through the defenders in multiple sectors, linking up far behind the lines, and encircling virtually all of the million-man of the Polish army. The Poles had fought bravely, even heroically in most cases, but they were simply outclassed. It was a typical result, of course, when a great power takes on a weaker neighbor, and probably what Stalin, Molotov, and the commanders on the Finnish front expected.

What they got, however, was something very different. Despite massive Soviet numerical and material superiority, absolute control of the air, and around-the-clock bombing of Helsinki and other targets that inflicted heavy civilian casualties, the first month of this conflict defined the term “military disaster.” For the Soviets, it was a perfect storm of bad.

Some of it was their own fault. The Red Army had greatly increased in size in the past two years, a reaction to the dark international situation; indeed, the army was in the process of growing from 1,500,000 men in 1937 to somewhere around 5,000,000 in 1941. At the same time, however, Stalin had been engaged in a bloody purge of his own officer corps, with 80% of the corps and divisional commanders accused of disloyalty and shot. The combination was disastrous: masses of poorly trained soldiers under officers who were either political hacks or who were scared to death of exercising initiative for fear of falling afoul of Stalin and the NKVD.

Some of it was their own fault. The Red Army had greatly increased in size in the past two years, a reaction to the dark international situation; indeed, the army was in the process of growing from 1,500,000 men in 1937 to somewhere around 5,000,000 in 1941. At the same time, however, Stalin had been engaged in a bloody purge of his own officer corps, with 80% of the corps and divisional commanders accused of disloyalty and shot. The combination was disastrous: masses of poorly trained soldiers under officers who were either political hacks or who were scared to death of exercising initiative for fear of falling afoul of Stalin and the NKVD.

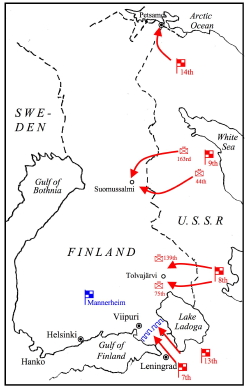

They also had not counted on the fighting quality of their enemy. Commanding the Finns was wily Marshal Carl Mannerheim. In this opening phase of the fighting, he successfully waged two wars at once. Most of his regular army (five of nine small divisions) was deployed in the south, along the 90 mile front of the Karelian isthmus. Here he built a strong fortified position, usually known as the Mannerheim Line—tank traps, trenches, machine gun nests, bunkers—and dared the Soviets to attack. They obliged, in clumsy frontal assaults that the Finns shot to pieces.

Nothing unusual there. Frontal assaults against fortified lines have a way of failing. In the north, however, along the 700-mile-long border, Mannerheim waged a much more diffuse guerrilla war. The Home Guard was the backbone of the defense in this sector, hardy citizen soldiers who knew every inch of the land, who were dead shots, and who could handle the cold. They were ski troops, coming up silently out of the forests, nearly invisible in their white parkas, raking the ponderous Soviet columns with machine gun fire and then vanishing back into the forest. Their weaponry was often crude, home-made gasoline bombs they called Molotov cocktails, for example. They made up for their crude weapons with the oldest soldierly quality of all, however: intestinal fortitude, guts, courage. The Finns call it “sisu.”

As bad as the stalled drive against the Mannerheim Line had been what happened in this sector was much worse. At Suomussalmi, two entire Soviet divisions (the 44th and 163rd) were ambushed, trapped, and destroyed in the forests. At Tolvajärvi, two more (139th and 75th), suffered the same fate. By Christmas, Finnish counterattacks had bro-ken up the invading Soviet columns into isolated, immobile fragments. They were starving, freezing, and surrounded. “Motti,” the Finns called them—sticks bundled up for firewood and left to be picked up later.

The Soviets had fought bravely in all these battles, driving gamely into the Mannerheim Line or digging in grimly in their motti positions, but their losses on all fronts were soon rising into the hundreds of thousands. Indeed, 505 of them fell to one Finnish sniper alone: Simo Häyhä. He earned the nickname “White Death” from his Russian adversaries, but frankly we could apply the nickname to the entire Finnish army in this war.

Why study the Winter War? Perhaps the most important reason is that it reminds us that war is a gamble. You can count the cannon both sides, assess the probabilities, haul out the actuarial tables, but you can never predict the outcome. By most standards of military accounting, the Winter War should be been a quick pushover for the Soviets. But that is precisely what separates war in the field from war in theory.